London, England

July, 1972

Centre Point and the Office Block Scandals

New Piccadilly Circus Plan

Save Covent Garden

Office Block Threat To Dock Land

We All Love London…Leave It Alone

No issue – not even the dock strike, floating of the pound sterling or final approval of British entry into the Common Market – has consistently been given so much attention in England’s headline-heavy, highly opinionated daily press in recent months as have the many controversies over runaway real estate development in London.

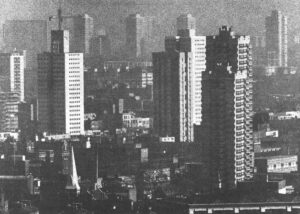

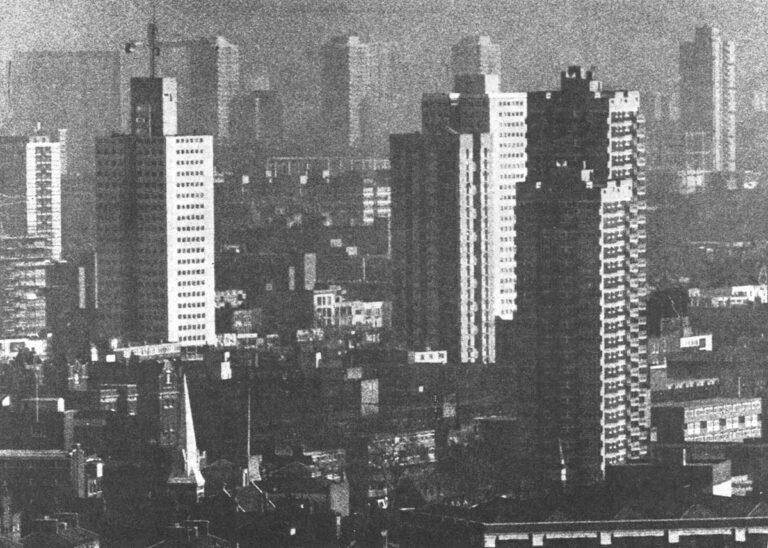

Already, all over the city, typical London neighborhoods with low buildings, small green spots, corner stores and animated pubs have been replaced by blocks of huge, lifeless office and apartment buildings. Massive new structures have squeezed out 18th century Georgian townhouses and 19th century Victorian curiosities in and around Bloomsbury and elsewhere in the popular West End. Stark concrete towers of public housing flats have risen on the sites of razed tenements and little shops in the working class areas of the East End and South London. Road widening projects have sent swollen rivers of traffic racing through close-in residential suburbs like Hampstead.

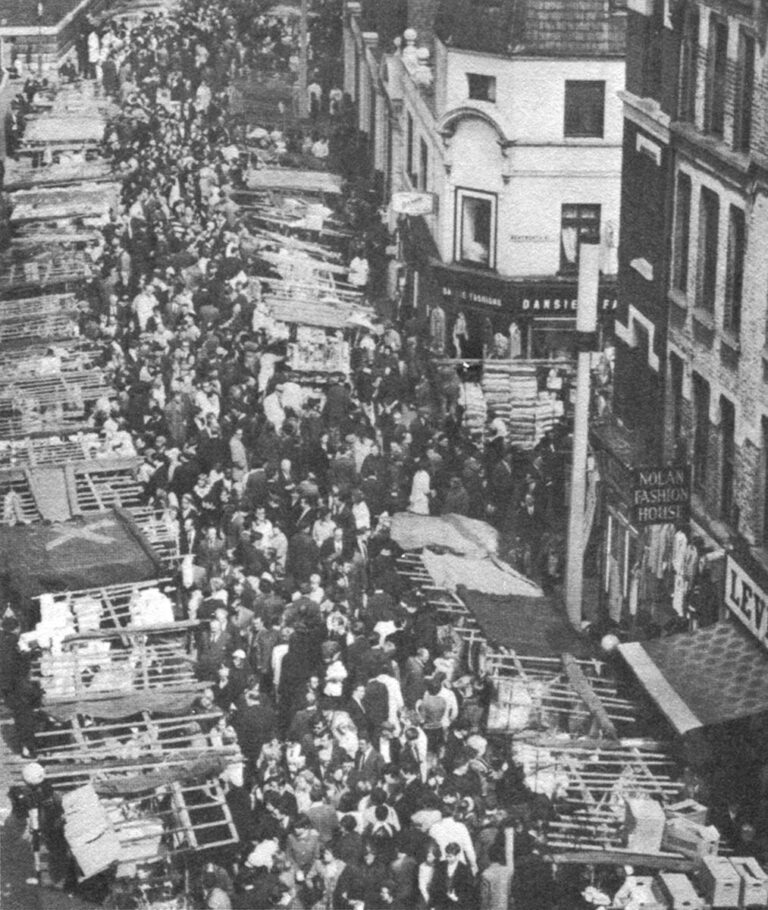

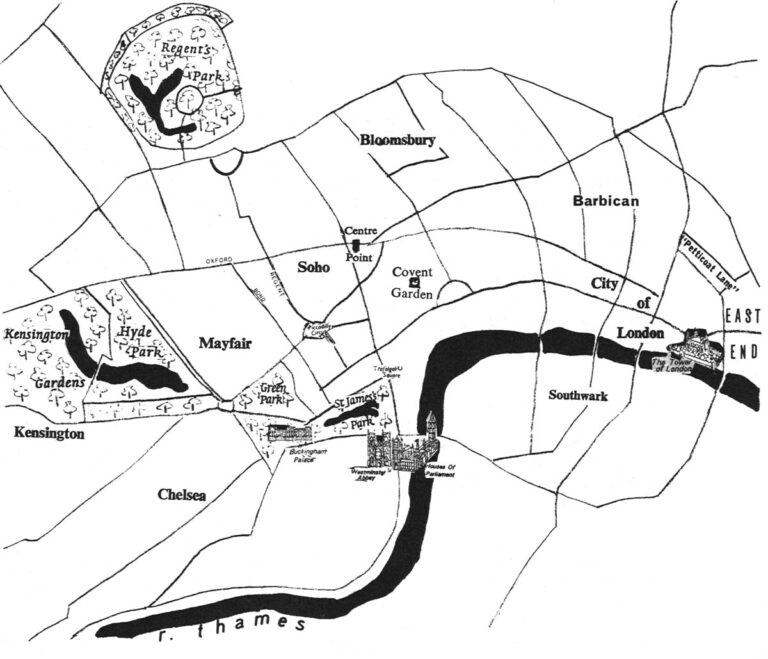

Still more of the city’s liveliest and most appealing enclaves are to be gutted and their present scale transformed by gigantic multi-building complexes and wide traffic arteries if final approval is given to controversial redevelopment plans for the Piccadilly Circus entertainment district, nearby Soho, the area around the Covent Garden central produce market, and the old Jewish neighborhood where the well known Petticoat Lane outdoor market fills several streets each Sunday. “The heart is being torn out of London,” a BBC radio commentator complained recently. And a Sunday newspaper discussion of the issue characterized the changes taking place as “the Second Blitz of London.”

Spurred by the press, Londoners are beginning to fight back against developers and government planners with as much determination as they resisted the original Blitz. The Save Piccadilly Campaign, which boasts united support from titled millionaires, show business personalities, the West End upper middle class and the “street people” of Soho, has at least temporarily blocked the most recent of half a dozen attempts in the last 13 years to change the face of the neon-lit theater district which is still as vibrant today as Times Square in New York City used to be. Covent Garden area residents have forced reconsideration of renewal plans there. Organized groups of squatters are taking over abandoned buildings that had been earmarked for razing. Dozens of citizens’ groups are fighting plans for a system of new freeways in the city.

At a recent mass meeting convened by the Save Piccadilly leaders, representatives of scores of other neighborhood conservation groups, from East End public housing tenants’ associations to Mayfair and Kensington homeowners’ alliances, decided to pool their resources, information and efforts citywide. Carried away by the sudden surge of citizen opposition to the developers, an Evening News columnist praised this “spontaneous combustion of citizen fury against men, some greedy, others merely misguided, whose plans would turn London Into a glass and concrete fortress so heartless that even the computers would try to break out.”

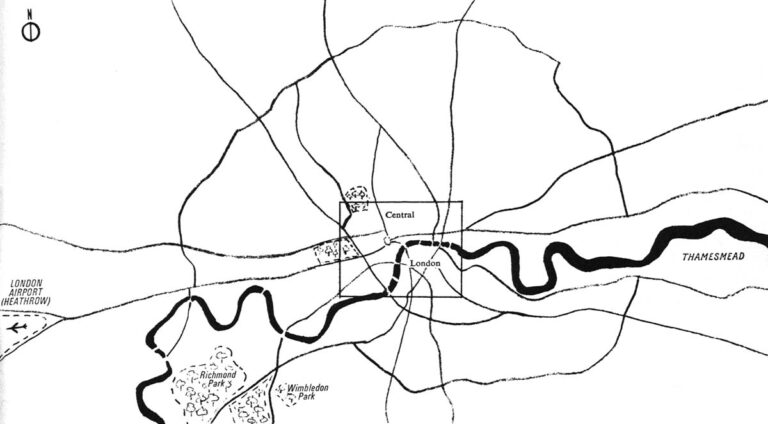

The ironic fact is that among these “greedy” and “misguided” men are the very government planning officials that have been getting credit from envious city officials in many other countries, particularly the United States, for making London, in the words of U.S. News & World Report, “one city that is solving its problems.” Much industry and population has been successfully removed from the congested inner city to government-planned “new towns” and “expanded towns” just beyond a protected 90,000-acre greenbelt of forests, farmland, tiny old villages and open space that girdles sprawling central London. Inside the greenbelt, London’s population has been decreased from 8.2 million to 7.5 million, while the stock of available housing has been increased from 2.3 million to 2.5 million dwelling units. Auto commuting into central London has been decreased, partly by the decentralization of the region’s employment and population and partly by expansion of London’s extensive, well-used subway, bus and commuter train systems.

Tough, well-enforced regional anti-pollution regulations have dramatically reduced smoke emissions into the air and industrial waste flow into the water of the Thames. Killer fogs have been eliminated and smog is rarer now in London than in almost any major U.S. city. Fish are returning to the Thames, which no longer smells and is much cleaner than, for instance, the Seine in Paris.

Much of this progress is due to the immense investment made in the capital city by the national government of Great Britain, which meets an estimated 40 percent of London’s expenses in one way or another. The new town and expanded town programs are also national projects, built with government loans for construction and tax incentives to industries that move to them. The commuter rail services are part of the national railroad network. Local public transportation and other services and improvements in London and other British cities also are subsidized by national government programs.

What happens in London is also strongly influenced, however, by a powerful government planning network extending from the new national Department of the Environment through the expanded Greater London Council to the local councils of the three dozen boroughs within the London region. The Greater London Council regional government now has planning authority over more than 700 square miles, from the one-mile-square City of London (known as “the City”) with its banks, brokerages and law offices in what was once called Roman and medieval London to new development beyond the greenbelt. The GLC directs the efforts against air and river pollution, builds and manages an enormous amount of public housing, coordinates regional transportation and, with help from the boroughs and ultimate approval from the Department of the Environment, plans and reviews all new development in London.

There are still big jobs facing the Greater London Council. Much of London’s housing, particularly in the East End, South London and the old warehouse and factory suburbs of the north, east, and south is old and dilapidated. The movement of many factories and warehouses out of these areas has left men without work and buildings without use. Conversely, there are not enough offices or homes for those who want them inside the City or in the fashionable western parts of London. And there is a growing fear that too many of the people who left London during the planned decentralization are middle class workers and residents, leaving behind a polarized city of the rich and poor with too few middle range homes or jobs to prevent London from ultimately suffering a Manhattan-like decline. So, after having labored hard to relieve congestion in London, the GLC now is planning for more housing, more middle level jobs (mostly in offices) and the rebuilding of rundown areas.

As is the case in the present redevelopment of Paris (See LD-8, Paris: Under Construction), however, critics are accusing planners and developers of achieving the promised progress at the expense of what has always made London an attractive city: its many individual neighborhoods, the low profile and density of much of its older housing, the period buildings and the familiar nooks and crannies that had survived the Nazi bombing and the fires before that. As in Paris, it is not redevelopment itself that the critics are worried about, but rather the emphasis on sweepingly large projects and gigantic buildings that result in less human surroundings for London residents but much bigger profits for land speculators and developers.

“To come back to London after even a brief absence is to realize all over again that in our infinitely abused capital city, almost all change is for the worse,” wrote a London Sunday Times columnist. “So much money is to be made from the de-humanization of London that it may be naive to suppose that it will ever be arrested. Perhaps it is inevitable, with things as they now are, that posterity will say, ‘By the end of the 1970s, London was unliveable.”‘

At the moment, there is still sufficient population and employment pressure in London to make trading in land values and speculative construction of new buildings spectacularly profitable. Office rents and building prices in central London are reputed to be the highest in the world, according to the British financial magazine-newspaper, The Economist, which pointed out recently that “more millionaires have been thrown up by the property business in Britain since the war than by any other industry.” Land values are rising so rapidly that some speculators are publicly offering up to 25 percent of the profit they make on resale to anyone offering them inner city buildings or land. To realize the financial potential of steadily increasing land prices, speculators must keep property in motion; developers must build new, bigger buildings. Conservation of what is good about old London does not interest them.

One controversial developer has even found it more profitable to let his new office buildings stand empty for long periods rather than to rent them out immediately after construction is completed. The developer, Harry Hyams, developed the technique with a used building of shops and offices that he bought on the busy West End commercial thoroughfare of Oxford Street for a price that indicated an annual rental value of 12,500 pounds. After taking the building over, however, he demanded an annual rent of 20,000 pounds, well above normal at the time. After the building stood empty for three years, on a street where shops and offices are never vacant for long, he succeeded, because of rapidly rising property values, in renting it for 18,500 pounds. Commercial property in Britain is valued on a capitalization of the annual rental income, so Hyams’ building was now worth 270,000 pounds on resale, rather than the 195,000 pounds it would have been worth if he had rented it immediately for, say, 13,000 pounds. His three-year delay in renting it thus gave him a capital gain of 70,000 pounds, against a loss of only 39,000 pounds In rent for the three vacant years and a relatively small amount of property tax he had to pay (the property tax being much lower on an empty building than on one fully rented out).

Since that time, companies controlled by Hyams have built four big new office buildings in central London with working space for about 4,500 office employees. But none has ever been rented. Each has remained vacant for years while their potential rental value climbs rapidly. One new building, an office tower called Centre Point that looms over the Bloomsbury neighborhood on the east end of Oxford Street, has been empty for eight years since construction on it was finished. Only security guards and their German Shepherds occupy the building’s 33 floors. When it was built, Centre Point would have rented for 4 pounds per square foot; today it could be rented for 8 pounds a square foot, but Hyams is asking for still more.

Hyams and his empty buildings made headlines in London recently when government officials became angry that so much new office space is being wasted while rents continue to soar and developers and planners demand that still more mammouth office blocks be built, in many cases where residences are now. Londoners are worried that office buildings will overrun central London and the West End, as they have mid-town Manhattan. The city’s planners, however, are more concerned about the high office rents and the need they see for more office jobs in London.

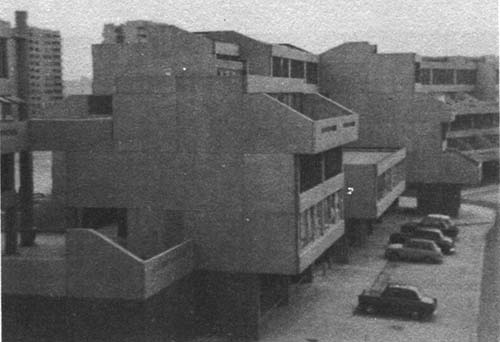

Not just the quantity but the quality of the new office blocks has come under attack, also despite the planners’ seemingly good intentions. In order to realize economies of scale and have enough room in each project to perform such desirable new tasks as separate pedestrians from automobiles, the planners have allowed and even encouraged developers to tackle big projects of many buildings, preferrably around central pedestrian precincts. Developers who desire maximum profits with minimum investment have been using this freedom to put up collections of monstrous, bland new buildings around uninteresting, bare pedestrian walks and malls.

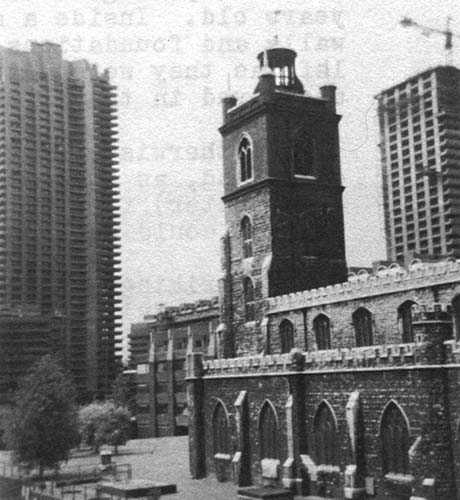

The warmth of the old narrow London streets is being replaced by cold concrete slabs. The most notable of these disasters are the St. Paul’s and Paternoster blocks of offices, shops and concrete walks and open spaces that surround St. Paul’s Cathedral in the City. When the planners have forced developers to add housing, it, too, has been provided in overpowering concrete blocks of flats devoid of neighborhood atmosphere or the little patches of green and flowers so important to the English. Ironically, the planners are proudest of the most disturbing projects because of the boost they give to the city’s economy (just as Parisian planners boast about the bulky Maine-Montparnasse renewal project and its awful 60-story tower); human environment is given a low priority.

The similarity of the goals of developers and planning officials is not always merely coincidental. With so much money to be made in rising property values, almost everybody with money is involved in the action. So, as often happens in the United States, people financially involved in real estate development wind up in the positions from which the developers are supposed to be controlled. Only recently, it was revealed that the top officer of the Greater London Council, Sir Desmond Plummer, had more than $50,000 invested in the three giant real estate firms that were seeking GLC approval of their plans to redevelop Piccadilly Circus. And an officer of the council of the borough of Westminster, where Piccadilly is located, is a member of one of London’s most successful families of builders. When the most recent Piccadilly Circus redevelopment compromise was unveiled in May to an almost universally skeptical public, it turned out that the GLC and Westminster council officers had negociated secretly with the developers and drawn up the new plan themselves, while leaving other council members, and the public, in the dark. In the furor that followed, the new plan was delayed for further study and Sir Desmond Plummer sold his stock in the three development firms.

While the West End of London may suffer from the efforts of planners and developers to put too much into it, the vast East End, flanking the wharves of the Thames, has just the opposite problem. National and regional plans to decentralize much of London’s industry and population have worked so well that the East End has been denuded of its most profitable industry and robbed of its most productive citizens. Left behind were docks and warehouses, which are now also being abandoned because of changes in cargo handling that favor docks further down the estuary towards the Channel, and unskilled and often unemployed labor, much of it immigrant. The East End now has little of the tax-producing business and none of the tourism of the West End, yet East End residents must help pay for city services. And their services are inferior, particularly public transportation. Far fewer subway and bus lines serve the east, even though the East End has fewer automobile owners than the rest of London. Most important of all, the East End contains London’s most dilapidated housing, a disproportionate share of the city’s poor and very little of its middle class.

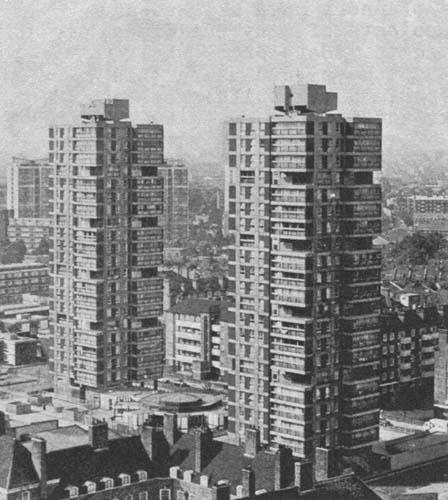

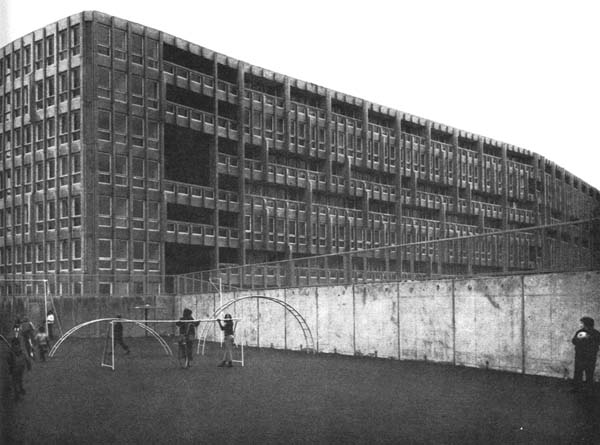

The response of the GLC and the East End boroughs to the problem has been limited mostly to tearing down old buildings – tarnished heirloom buildings and still liveable neighborhoods along with the slums – and putting up high rise public housing. The bulldozing has left much of the East End looking as London must have during the Blitz, except that huge slabs of apartments rise high above the rubble like giant gravestones in a cemetery. Although this housing is widely disliked for its appearance and anti-social nature, it is physically better inside than much of the housing in the East End and therefore is snapped up by the low-income families on the long public housing waiting list. Because the list is so long, middle income families cannot get into the new East End flats, as they sometimes can in public housing elsewhere in London; this increases the middle class exodus from the East End.

As impoverished as much of the East End is, however, it is already being eyed greedily by real estate speculators. They want to build colonies of offices on the 5,000 acres of now unused dock space that stretches for miles along the Thames like a waterside ghost town. This would do little for the East End community because the majority of its labor force could not work in the offices and the area has little housing for middle class office employees. Only the speculators, who could buy the dock land relatively cheaply, would benefit. Yet GLC officials are showing interest in the speculators’ proposals because of the overall demand for more office space in London.

A minority on the GLC has urged that the dock sites be used for new housing for East Enders and industry that would employ its less skilled labor, with any profit realized from rising land values being put back into the East End community. This idea was carried further by the influential magazine, Architects’ Journal, which called for designation of the East End as an official British new town project. A public corporation could then be put in charge of redevelopment and, with the proper leadership, according to the magazine, could build what the East End needed most, including housing for new middle class residents, and use land profits to pay for needed public facilities. The magazine also emphasized that redevelopment should retain both the area’s scattered but numerous interesting buildings and the trappings of the strong social fiber that still holds together the working class neighborhoods that have not either degenerated into slums or been uprooted by renewal.

Unfortunately, much of what had made old East End neighborhoods seem like home has already been destroyed by the bulldozer and replaced by the lifeless new buildings. As part of the campaign to save the too little that is left, East End residents have opened an exhibit of photographs of streets and buildings recently demolished. They were rundown buildings and undistinguished streets that were clearly expendible in the eyes of middle and upper class planning officials, but they contained the curious little shops and familiar old stores that had meaning for the lower class residents of those streets, something sadly lacking in the new public housing towers. “If the surroundings (of the old streets) appear bleak and old,” wrote the author of the exhibit’s brochure, “it’s because the struggle to survive is bleak and old.”

This kind of every day reality is often difficult for London’s planners to grasp. Planning in England is a decidedly paternalistic exercise with powerful planners more or less imposing what they think is best on a helpless public, with almost no feedback or participation in the planning process by ordinary citizens. “As a profession, we are very self-critical and that is healthy,” John S. Millar, the new president of the Royal Institute of Town Planning declared recently. “But I think it is rather important at this juncture that we recognize that British planning, with all its defects, is probably the best in the world.” With the advent of Common Market membership, he said, British town planners “must blow their trumpets a little at the gateway of Europe.” He dismissed the present public displeasure over much that planners and developers are now doing in Britain as a mere “occupational hazard.”

It is true that British planners have done an admirable job of making the necessary large scale replacements of bombed out city centers (in Coventry and Birmingham), removing really wretched, irredeemable industrial inner city slums (Sheffield), and preserving with careful renovation the old buildings and atmosphere of historic towns (York, Durham, Lincoln and Winchester among many fine examples). But they have not been as successful in creating liveable new residential neighborhoods, particularly in the larger cities, as they have been in preserving and rebuilding monumental public areas. Unfortunately, the housing also has been monumental, attractive to planners in their architectural drawings and to cooperative developers on their ledger sheets, but inhuman in reality. The apartment towers of London’s East End or Birmingham’s new housing estates resemble only too well the depressing public housing projects of U.S. cities. Mr. Millar’s boasting notwithstanding, British city planners have in recent years fallen behind their counterparts in Europe in experimenting with ways to give new big city housing developments human dimensions and community life.

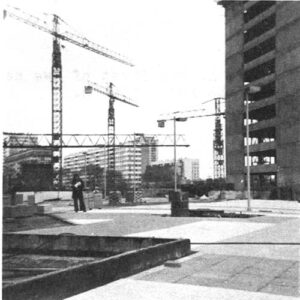

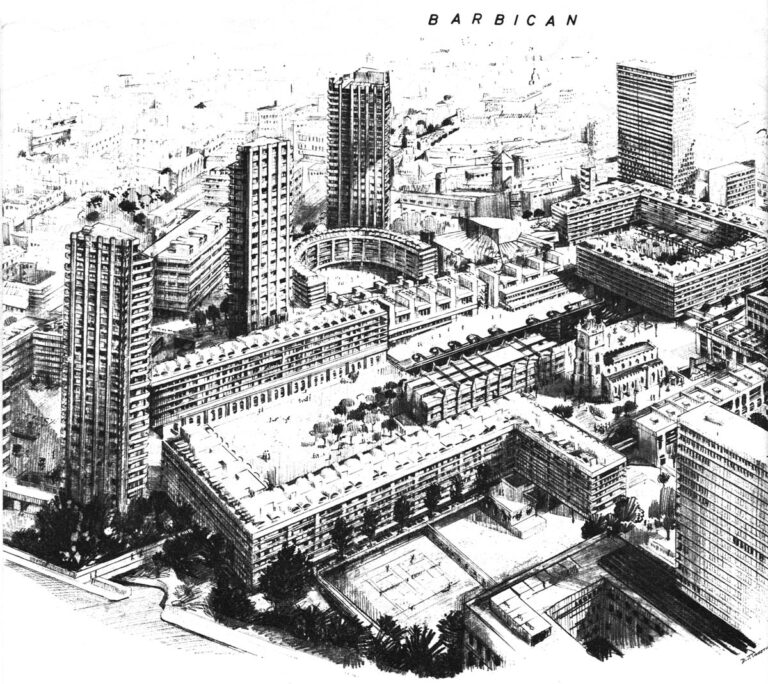

It happens, however, that there are now two new projects underway in London that do attempt to come to grips with this problem. Although the planning of each of them still reflects too much detached paternalism, the results are more promising than anything else in London. One of the projects, called Barbican, is the complete redevelopment of 60 acres of land in the independent city borough by its government, the Corporation of London. The other is Thamesmead, a so-called “new town in town” with housing being built under the sponsorship of the Greater London Council on 1,300 acres of drained and filled marshland on the south bank of a bend of the Thames River in the far East End of London.

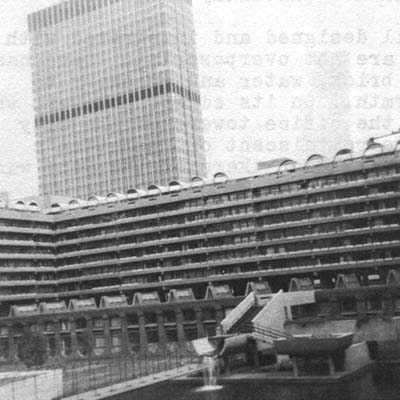

In some ways, the projects are quite different. Barbican is being built for the rich with luxury apartments, offices and a large and expensive arts center in the middle of London’s financial district, while Thamesmead’s primary purpose is to provide badly needed new housing, much of it public housing, for workers in the heavy industry still operating around the wharves on the southern bank of the Thames. But the planners of each project are making use of the same new physical techniques – vertical separation of pedestrian and auto circulation systems, varied living levels, integration of housing, commerce and public facilities, and the inter-connection of buildings of varied sizes and shapes but similar exterior facades into one flowing architectural whole – to try to create the appearance and atmosphere of community. Both projects, still in the early stages of development, also are distinct breaks with the past for their respective situations.

The Barbican development has been a source of controversy within the Corporation of London for almost two decades. A century ago, 100,000 people lived in the mile square City, which supports itself handsomely with taxes on its lucrative financial tenants (tax money it shares with the Greater London Council, as all London boroughs do) and revenues from the considerable land it owns all over London. As the financial center grew, however, offices pushed out more and more residences (a process begun in the Middle Ages). After the Blitz destroyed half the City’s buildings, housing for just 5,000 people was left, although the City’s daytime population of workers exceeds half a million.

After it was decided in the mid-1950s to rebuild the war devastated Barbican area as a single project, the men of means who make up the Corporation of London’s government argued for years over whether the site should be renewed only for commerce or for a combination of commerce, housing and a new center for the arts in an attempt to restore some semblance of 24-hour life to the City. One Lord Mayor of the City, Sir Edward Howard, had fought the arts center particularly hard, arguing that “art makes less contribution to civilization than the internal combustion engine.” Other voices pointed out that housing would be a considerably less profitable development investment for the corporation than offices, especially on such high-priced land. The drawn out discussion and subsequent labor and contractor problems delayed the project for years.

BARBICAN

BARBICAN

Within boundaries marked by concrete and glass canyons…

trees, shrubs and grass have been planted,

water has been sent cascading into pools;

a Blitz reminder,

a Blitz reminder,

and an old church have been saved.

The advocates of a functionally mixed project triumphed in the end, although only 6,000 people will be housed in the new luxury dwellings that can be expected to be quite profitable for the City, at rents beginning at $300 and $400 a month. The project is to include some 400-foot-high apartment towers and larger, lower buildings, the arts center of concert halls, theaters and an art gallery, shops and restaurants, a school, an artificial pond, canal and fountain system, gardens, underground parking and pedestrian malls and bridges. Much of this is now partially completed.

The big buildings are so well designed and integrated with smaller scale amenities that they are not overpowering. Care has been taken to integrate concrete, brick, water and greenery to give the project some physical warmth. On its edges, however, where Barbican’s biggest buildings abut the office towers of the City around it, there is atmosphere more reminiscent of Manhattan’s canyons, which may or may not be what the bankers of the City want.

The most appealing aspect of the project at this stage is its system of walkways, pedestrian bridges and malls, which give the pedestrian sanctuary from London’s threatening traffic while leaving him exciting vistas of the city around him, access to all the buildings, stores and attractions of Barbican and unexpected views of water, garden and, best of all, protected islands of relics of the city’s past. There are excavated fragments of the old Roman city wall and one of its gates, nearly 2,000 years old, and an imposing tower from the Norman fortifications, almost 900 years old. Inside a small memorial park, a collection of battered walls and foundations of medieval and more recent times have been left as they were, after the buildings they were part of, were destroyed in the Blitz.

Otherwise, Barbican is being built by the elite for the elite and, as such, has little importance itself (except as an arts center) for the rest of London. But the techniques it is testing could well be studied and adopted elsewhere in London.

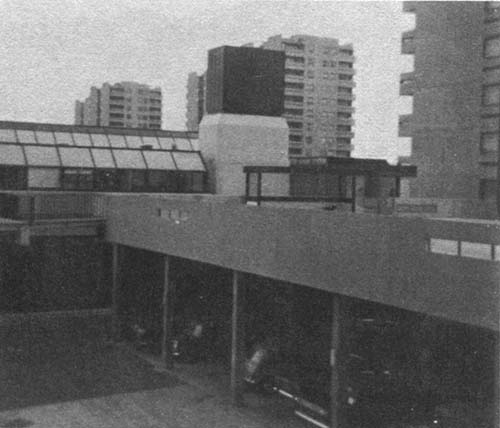

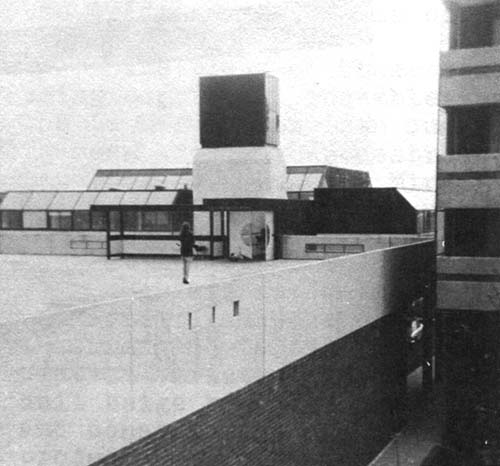

Strikingly similar methods are being used in what is to be socially a quite different community at Thamesmead. A much larger project than Barbican, Thamesmead is also considerably more residential and will house 60,000 people when it is completed, although a full range of shopping, recreation and public services are to be provided in neighborhood centers and a large town center big enough to become a commercial and cultural attraction for much of the under-serviced East End. Thamesmead’s concrete buildings and raised pedestrian malls and bridges, all of unusually attractive design for a factory-built project (using the French Balency industrialized housing system), strongly resemble those of Barbican.

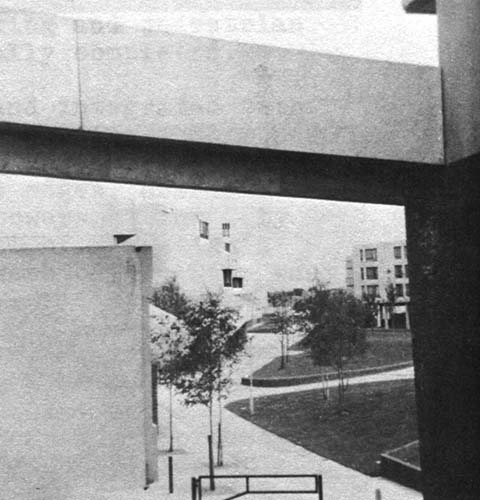

Varying levels for living in Thamesmead: high-rise buildings, pedestrian bridges and raised concrete malls with parking levels underneath. Note modern design of community health center at left and neighborhood shopping center on pedestrian mall in photos below.

Unusual home shapes, lakes and canals, pedestrian malls, plots for trees, and grass make Thamesmead outwardly attractive.neighborhood shopping center on pedestrian mall in photos below.

From Thamesmead’s planned commercial and social center overlooking the Thames, arms of high-rise housing built along raised pedestrian avenues will radiate in several directions, with the tall buildings forming wind and noise screens along the river, a freeway that is supposed to run through the site and the project’s own wide auto thoroughfares. Within these protective walls are to be lower residential buildings, open spaces and lakes fed by the site’s drainage canals. The network of walkways will reach every spot in the project, with the elevated malls leading first to neighborhood pedestrian “streets,” along which stores, schools and recreational facilities are to be located, and then to meandering paths in parks and along the lakes, canals and riverfront. Embankments and canals will run alongside primary auto roads to make it impossible for pedestrians to walk on these roads or to cross them except via the bridges and tunnels of the pedestrian circulation system.

The plans of Thamesmead, and the first two neighborhoods now being completed, resemble the most advanced new towns of Israel and the Le Mirail new town quarter of Toulouse, France, although Thamesmead’s auto-pedestrian separation will be even more strict than theirs. Like Le Mirail and the Israeli new towns, Thamesmead’s neighborhoods of a few hundred families each will tend to merge together into a few district quarters grouped along spines of the largest buildings and wide pedestrian ways. Thamesmead’s bigger buildings are not so massive nor so tightly arranged as those of Le Mirail; rather they are well integrated with lower structures in arrangements (as in Arad in Israel) that give Thamesmead more spatial variety, although all buildings at present have the same dull beige pre-cast concrete appearance. Their individual designs and construction still are unusually attractive for this kind of project – in contrast to the stark slabs put up as public housing elsewhere by the Greater London Council.

Thamesmead’s massive, rough hewn scale, while pleasing to a visitor’s eye, may not necessarily function well as a living community. Something more than the waterways and grassy open spaces will be needed to break up the concentrations of concrete, so that adults can enjoy urban variety in their surroundings and children will have exciting places to play. Except for an attractively designed health center and a local betting shop in the first small commercial center now open, there is little evidence of imaginative social planning for Thamesmead. It remains to be seen whether enough activities (recreation facilities, schools, more shops) and physical amenities will be placed along the project’s walks to give people reason for and enjoyment from using them. There is also some question whether Thamesmead residents will be sufficiently protected from the noise and irritation of both their own wide high-speed road system and the big freeway that is supposed to cut through the center of the development.

Stations on a commuter rail line to central London are located on Thamesmead’s southern edge, but it appears that most of the project, located quite far north of this line, will be dependent on auto transportation. Places of employment, including existing riverfront industry around Thamesmead’s site and new business the GLC hopes to attract, also are supposed to be reachable by foot, bicycle and bus in the future. Socially, however, Thamesmead is isolated on a bend of the river by massive wharf-side factories from the rest of London, and it will have to possess some spark of life of its own.

There is the danger that Thamesmead may share the fate of Chelmsley Wood, a similarly large housing estate just completed east of Birmingham for 60,000 families who have moved out of slums in the crowded industrial city. Chelmsley Wood has been well supplied with shops, public malls, a complete pedestrian walkway system, schools, health services and lavishly landscaped grounds. But the project is just as woefully short on social facilities as its dozens of matching apartment towers are lacking in human scale. There is no place on the landscaped green places for a game of soccer, and ball playing of all kinds is forbidden in the garage driveways. A “multi-purpose entertainment center” in the commercial center is used only for bingo seven days a week. There are no cinemas, public swimming pools or youth centers. Because there is no day care for children of working mothers, many children wear their house keys on strings around their necks in school and wander by themselves through the project with nothing to do until parents return home at night. Vandalism and teenage gang activities have become enormous problems in the six years since the project was begun. The modern housing and impressive physical amenities of Chelmsley Wood are appreciated by the families who moved there, but the project is cold and uninviting socially, a lesson that should be heeded by Thamesmead’s builders unless Chelmsley Wood’s mistakes are to be repeated.

Although private developers will be building some dwellings for sales to owner-occupants at Thamesmead, most of the housing will be provided by private builders under contract to the Greater London Council for ownership and management by the GLC itself, the local borough housing authority and non-profit housing groups. These dwellings will join the hundreds of thousands of rental units in greater London’s stock of “Council housing”, as public housing is called here. Prospective tenants may come from any income level, but higher priority is given to those displaced by renewal and to families with lower incomes and more pressing housing needs.

Despite its mixed income clientele, however, too much Council housing, from old Victorian tenement-like flats built around bare asphalt yards to the unpopular modern towers still being built by the GLC and borough authorities in many locations today, is monolithic, socially vacuous and lacking in recreation facilities, shops and green spaces. Too little has been done to rehabilitate existing privately owned buildings for modern Council housing use. The problem the planners face is that of building into new projects enough community life to replace the socially viable if physically rundown neighborhoods that are destroyed to make way for them. This is where both public and private projects have failed most miserably, leading Londoners to fight all new development, even where the right changes could produce improvements.

Public or “Council” housing: from old to new, the quality of living remains unchanged.

But London’s planners, with all their freedom, have simply not been coming up with the right answers. Their efforts have been heavily influenced by the profit aims of developers and pressures of rising land values. Thus, while improvements in the quality of London’s air and water should serve as a good example to Americans of what powerful regional planning can accomplish in a big city, the problem of planning well for new housing and office development in London should provide a warning that planning power is not enough. It must be used with imagination and a realization by planners of the social needs and desires of the people they plan for, which probably requires some direct participation by those “client” people in the planning process itself, an unimaginable situation in the paternalistic pattern of city planning in London.

Received in New York on September 22, 1972

©1972 Leonard Downie, Jr.

Leonard Downie, Jr. was an Alicia Patterson Fund Foundation Fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Downie, the Post and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.