Steve Sinko, a top labor troubleshooter at Bethlehem Steel, was summoned for an emergency assignment on March 26, 1982. About 400 people were demonstrating in front of Martin Tower, headquarters of Bethlehem Steel in Bethlehem, Pa., as the United Steelworkers union protested “excessive salaries” paid to Bethlehem Steel executives. Sinko was sent to meet them at the door.

The union was complaining that while steelworkers were being asked to give concessions in a period of hard times, the corporate officers were getting big bonuses. Proxy statements filed a few days earlier indicated that Donald H. Trautlein received $555,986 in 1981, nearly double the $280,880 he was paid in 1980, when he was executive vice president for five months before being named president.

Sinko never had to face the protesters because the demonstration ended as peacefully as it began. However, he felt flattered that the company had turned to him in a situation that had potential for big trouble.

Yet, within the next year, Sinko was cut from the payroll. Without an inkling of what was coming, he was called into the office of his longtime personal friend, Anthony St. John, the assistant vice president of industrial relations, and informed there no longer was a place for him in the company.

“I left shaking,” Sinko, now 54, recalls. “I had just refinanced my house the year before and was facing $1,000-a-month mortgage payments…Tony said there was nothing he could do. All of labor relations was being obliterated.”

It was ironic that Sinko, a highly respected grievance negotiator–the person chosen to defend Trautlein against clamoring demonstrators–was among the first to feel the pain of the new chairman’s plan to save Bethlehem Steel.

But many thousands of similarly once-secure people would soon experience the same trauma.

Trautlein, chairman at Bethlehem for less than four years, was among the first of the nation’s top steel executives to recognize that drastic measures were necessary to jar the American steel industry out of a terminal pattern. After one year of sizing up his job, he closed down marginal operations, sold off all the West Coast plants, spun off all the ship repair yards, and even shut down steelmaking entirely at Lackawanna, N.Y., once the nation’s fourth largest steel mill.

Furthermore, Trautlein cut his own pay, and everyone else’s. And he sent shock waves the full breadth of the 21-story Martin Tower headquarters building-as well as every Bethlehem plant office elsewhere–insisting that all traditionally untouchable white collar jobs be justified or eliminated. Today, the salaried work force is 40 percent less than when he took over and no one knows when the ax will stop swinging.

During all this, Trautlein also assumed a leadership position in the industry’s fight against imports. He convinced the United Steelworkers union to join in an unusual management-labor suit to seek remedies from government. On another front, he plied a steel congressional caucus with data and urged all steel town citizens to write their legislators in support of a bill that would limit foreign imports to 15 percent of the domestic market.

Tennis-Playing Executive

In an industry usually dominated by austere men who rose to the top after years in steelmaking, Trautlein, an amiable, slightly plump tennis-playing executive, is an unlikely head of the nation’s number two steelmaker. When he became chairman in 1980, he was the first outsider not groomed in Bethlehem’s elaborate internal management training system. In fact, he had been with Bethlehem only three years before making it to the top–almost unheard of in an industry where most spend decades climbing the corporate ladder.

Trautlein, 57, is an accountant by profession. He spent 25 years with Price Waterhouse and was a senior partner there when in 1977 Bethlehem Steel chairman Lewis Foy recruited him to join Bethlehem as a vice president. If Trautlein did not know a blast furnace from an open hearth, he did have one advantage. He had handled the Bethlehem Steel account during nearly all of his years at Price Waterhouse, and no one knew the fiscal numbers on Bethlehem any better.

“I saw Bethlehem Steel as a well-managed company that ought to have a reasonable future,” Trautlein recalls of his decision to come. But that comfortable outlook of Bethlehem Steel began to change drastically on the very year that he joined the company.

Disasters swamped Bethlehem Steel in 1977. A savage winter blizzard shut down the coke works and snowed in the blast furnace operations at the Lackawanna, N.Y. plant. The Little Conemaugh River spilled its banks during a torrential rain and its raging waters cascaded through the Johnstown, Pa. plant, leaving a costly cleanup and closing some operations permanently. Fire crippled the Bethlehem Steel coal mine in Cambria County, causing extensive losses. On top of that, a mini-recession left the entire industry limping with unutilized capacity.

In 1977, for the first time in 50 years, Bethlehem failed to show a profit. Not only that, but the loss of $448,200,000 for that year was one of the largest ever reported by a corporation. Production workers had to be laid off by the thousands, and for the first time in its modern history, dismissals of salaried workers were necessary. On Sept. 30, 1977, a day remembered as “Black Friday,” 2,500 white collar workers were cut from the payroll across-the-board to conform to what the company said was a 10 percent reduction in steelmaking capacity forced by suspended operations in Johnstown and Lackawanna.

Modest profitability returned in the next two years, but the mood was hardly upbeat when Foy gave up the chairmanship to Trautlein in June, 1980. By now the signs of permanent disaster confronted the steel industry.

The cyclical boom years had ceased and plants everywhere were trapped in over-capacity and runaway costs. Steelworker wages were running 60 percent ahead of the average factory worker; 30 percent had been the historical level. Many once-exclusive markets, notably rods, wire and light structurals, had been almost entirely captured by foreign producers and domestic mini-mills, both able to underprice the integrated mills by large margins because of lower labor costs and more flexible work rules. Also, steadily rising steel prices had by now inspired the development of a variety of substitute materials in construction, automaking, and consumer goods, shrinking even the most reliable markets.

Bethlehem was particularly vulnerable for two more reasons. It had resisted diversifying during the high-profit years, insisting up until only recently that it stick to doing what it knew best–making steel. It also was over-staffed with white collar workers, many of them hired on the basis of wildly overoptimistic projections and many retained beyond their usefulness out of old loyalties that blinded practical decisions. Analysts with leading investment firms commonly gave Bethlehem the dubious honor of having the most management employees per ton of steel produced.

A systematic dismantling of the nation’s overbuilt smokestack industry was inevitable. Bethlehem Steel became a leader in the painful restructuring.

“We had a rationalization job to do,” is the way Trautlein described it in a recent interview at Martin Tower. Sitting around a cluttered desk that never would have been tolerated by his more meticulous predecessors, he spoke with frequent shrugs of sadness. “We had to look at each of our product groups to see how we stood with the competition, where we were out of the running, and what would continue to grow.”

Trautlein admitted sheepishly that “rationalization” had begun before he became chairman but it had one weakness: the people who had been doing the study had been chosen from the inside: “They had a vested interest. Everybody was for their own thing.”

Unlike previous chairmen who had come up through the ranks, Trautlein owed no clique or department a favor. He hired an outside consultant, former Harvard Business School professor Paul Marshall, to bring objectivity into the study. “We spent a year in long hours–besides running the day to day business–in trying to strategize, if you will, our company…and then we set out to do what had to be done.”

The first thing to be done was to reduce layers of excess salaried workers. Virtually each work station had to pass a function analysis that had two principal tests: 1. Is what we are doing here cost-effective, can we do it with our own people or can we do it better with outsiders? 2. With the declining capability in making and shipping steel, do we need this overhead?

Blue collar workers had learned early in life to plan their living scale knowing that working at steel would be cyclical, but white collar workers at Bethlehem had been always protected during the lean years and even during prolonged strikes. Getting a salaried job at steel meant security for life. While tremors of “Black Friday” in 1977 had not been forgotten, they were viewed as a phenomenon of the past. So, despite unceasing reports of company losses, many salaried workers went on assuming new mortgages, buying new cars, and entering into lengthy loan commitments.

Not surprisingly, the function study showed that jobs had collected like barnacles since the boom years. Bethlehem could make steel, Trautlein concluded, without even many complete departments. Not only was Industrial Relations “obliterated,” as Sinko was told, but so were nearly all service departments–photos, library, reservations, cafeteria, corporate security, chauffeurs, country club grounds crews, employee banking, and advertising. The services still deemed necessary were contracted out. And no department escaped pruning in the “ongoing consolidation of corporate functions,” which forced many more dismissals.

The trauma of the new white collar cutbacks was devastating. Secretaries and file clerks, many with no more than a high school education, were suddenly discharged from jobs paying between $22,000 and $25,000 a year. Overnight, they were cast into the real world where the going rate for similar skills was barely half that.

Some likened the dismissal ritual to a death row. An employee would be called into one office and informed his or her position was no longer required. More than a few became hysterical. A shocked employee would then be led to an adjoining office where standing by were “Main Stream Access” counselors trained to handle trauma situations. They were ostensibly there to provide help with resumes and career guidance. However, they had to do much more. They did the consoling and some even drove distraught employees to their homes, staying with them until the shock subsided.

The more fortunate victims in the staff reductions were those who were persuaded to leave through financial incentives. Management level employees with an adequate combination of age and years of service were paid lump sums to take early retirement. The so-called “carrots” were calculated on the basis of pensions that the company would have had to pay according to actuarial life expectancy. It was common to hear of supervisors leaving with a $250,000 to $300,000 lump sum. Higher echelon officers left with much more. In 1982 alone, 13 vice presidents who took “the lump” left with severance packages exceeding at least $1 million apiece.

Union officials said that eavesdropping cafeteria workers would make mental notes of lunchtime conversations comparing lump sum payments and then relay the intelligence to steelworker union headquarters–at least until the cafeteria staff, too, was obliterated. The hefty severance payments for salaried employees provided considerable ammunition in the union’s refusal to grant pay givebacks and work rule concessions. They remain a sore point with labor to this day.

“I thought at first we could trim through attrition,” Trautlein said. “But the recession in 1982 set us back some more. We had to accelerate (dismissals) and by the end of the year, it was clear we hadn’t done enough. We decided at that time we really had to pull the plug on Lackawanna.”

Located on Lake Erie in the northwest corner of New York, Lackawanna finished last on the list in the plant-by-plant projections for the future. Despite a costly new bar mill opened there in 1976, Lackawanna had gone steadily down hill. As Trautlein saw it, the market for steel had moved westward and that market could best be supplied by Bethlehem’s relatively new plant at Burns Harbor, IN, or by the Sparrows Point plant in Maryland, which has a good port for ocean shipping.

On Dec. 27, 1982, amid Christmas week gaiety, Lackawanna was stunned by an announcement from Bethlehem Steel: Lackawanna’s integrated steelmaking operations, primary mills and hot strip mill, as well as certain finishing facilities will be terminated. So would the jobs for 7,300 workers.

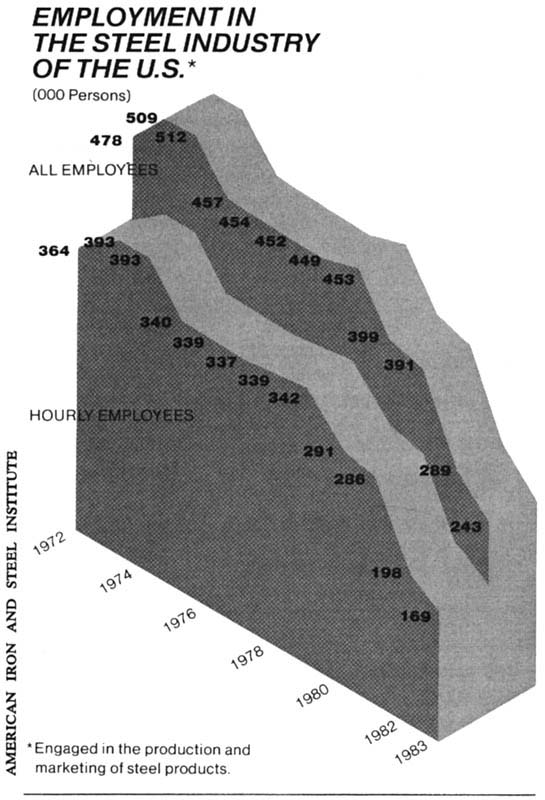

Bethlehem Steel’s total employment, which stood at 83,800 in 1981, was down to 52,000 by the end of the summer of 1984, a shrinkage of 37.9% in little over two years. These were jobs that will never come back. And these were only Bethlehem’s casualties in a down-structuring that now was remaking the nation’s steel industry. According to the American Iron and Steel Institute, steelworker jobs vanished industry-wide during the same period at almost the same pace, from 391,000 in 1981 to 246,000 in mid-1984, a 37.1% decrease.

However, even Trautlein’s drastic reductions at Bethlehem did not return profitability. While they reduced the operation’s break-even point and improved the ratio of tons of steel per man-hours, the peril to the future of the company did not go away.

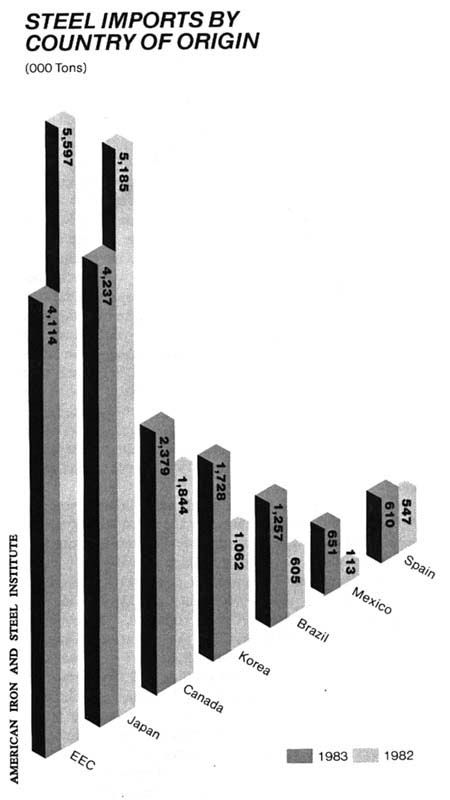

Bethlehem Steel lost $1.6 billion in 1982 and 1983. Accelerating imports of often subsidized foreign steel now were eroding up to 27 percent of the market by mid-1984, mini-mills were taking away another 25 percent, and the industry was still saddled with the most expensive labor contract in all of manufacturing.

The only two places left to look for relief were the government and the steelworkers union. Trautlein set out to tackle both.

Without waiting for the blessing of U.S. Steel, the major producer, Bethlehem teamed up with the union and in February of 1984 filed a petition under section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 asking for protection from all countries that ship steel into the United States. It asked the International Trade Commission for a 15 percent quota on all steel imports for five years, the same quota sought in legislation introduced by the congressional steel caucus.

By a 3-2 vote, the ITC in July supported the claim that the domestic industry was being damaged by foreign steel shipped here at unfairly low or heavily subsidized prices. It recommended that the administration impose quotas and tariffs for five years to protect about 70 percent of the domestic steel market.

Faced with a difficult decision in an election year, President Reagan chose to reject formal quotas and decided instead to force foreign nations to accept negotiated restraints covering all steel shipments. Trautlein greeted the President’s decision, but the union called it only a promise likely to vanish after the election.

In agreements announced last December, seven major steel-exporting nations agreed to reduce steel shipments to the U.S. by 30 percent, which will limit steel imports to about 18.5 percent of the domestic market during the next five years.

The quest for concessions from the union has not been easy, either. Even though the big steel companies reported combined losses of $6 billion for 1982-83, the steelworkers union twice rejected steel contract concessions that would have reduced their rate which by late 1982 stood at an astonishing $26.29 an hour, counting fringes. When a contract reopening agreement was finally reached, in March of 1983, the givebacks looked to many as more cosmetic than real. Steelworkers gave up 13-week vacations, among other extreme fringes, and accepted a $1.25 an hour cut. However, they agreed only on the condition that the pay cuts be restored by the time the renegotiated contract expires in 1986.

However, the industry-wide bargaining team could do little about relief from the archaic work rules and past practices that are also at the root of the industry’s inability to compete. While the companies won a right to negotiate work practices on a local basis, no substantial concessions have been reported and the multiplicity of crafts within the union are testy on yielding the slightest even though most of the objectionable work practices date back to the boom years.

Yet, union presidents are far less militant than they used to be. Life has not been easy for them, either. The international membership of the United Steelworkers Union is down by 50 percent, according to reports at last fall’s convention. Times in Bethlehem are so hard that union presidents try to pick up a couple of days of work at the plant to forego drawing a full week’s pay from the union treasury. In fact, a reporter visiting union headquarters in Bethlehem is likely to hear them singing the praises of Don Trautlein.

“Without Don Trautlein, I don’t know if we’d be in existence,” says Ed O’Brien, president of Local 2598. “He cut the fat which had to be trimmed.” Emilio “Chico” Curzi, president of USW Local 2599, even admits that the union laid a bum rap on Trautlein in the 1982 march at Martin Tower to protest Trautlein’s pay increase. “I think Trautlein is worth that kind of money. But it was the lump sum pensions and all the salary increases. I think we took our frustration out on Trautlein and it was wrong.”

However, when the Bethlehem plant tried to implement a Trautlein money-saving edict by hiring an outside contractor to reline a blast furnace as recently as last September, the union conducted another protest march, walking the streets with signs proclaiming that the Trautlein policy was taking jobs away from steelworkers.

Both management and labor insist rapport has improved. They point out the union is now welcome to express its views to improve the company at the highest echelons. And worker grievances are far fewer. But the message of the bottom line is far from optimistic. The company did report a slight profit ($24 million in the second quarter of 1984) after nine consecutive quarters in the red, but most analysts see more red ink ahead.

While the steel companies have pledged to modernize in return for protection from foreign imports, the commitment is unlikely to amount to more than salvaging modernization plans stalled or cut back in these hard times. In Bethlehem’s case, any immediate capital will be used to carry out modernization at three core facilities: the Bethlehem plant, which is a major producer of structural steel; Sparrows Point, Md., one the largest plants in the world, and at Burns Harbor, Ind., the last new integrated steel plant built in the United States, but one already in need of modernizing.

However, can any new technology produced in the breathing period of protection against foreign steel cure an ailing industry locked into the world’s highest wage rates and archaic work practices? The answer inevitably boils down to another question: How much more are the steel companies and the steel union willing to do to save themselves?

© 1985 John Strohmeyer

John Strohmeyer, editor and vice-president of the Bethlehem (Pa.) Globe-Times for 28 years, is chronicling a steel company’s battle to survive.