By Bill Berkeley and Photos by Mary Jane Camejo

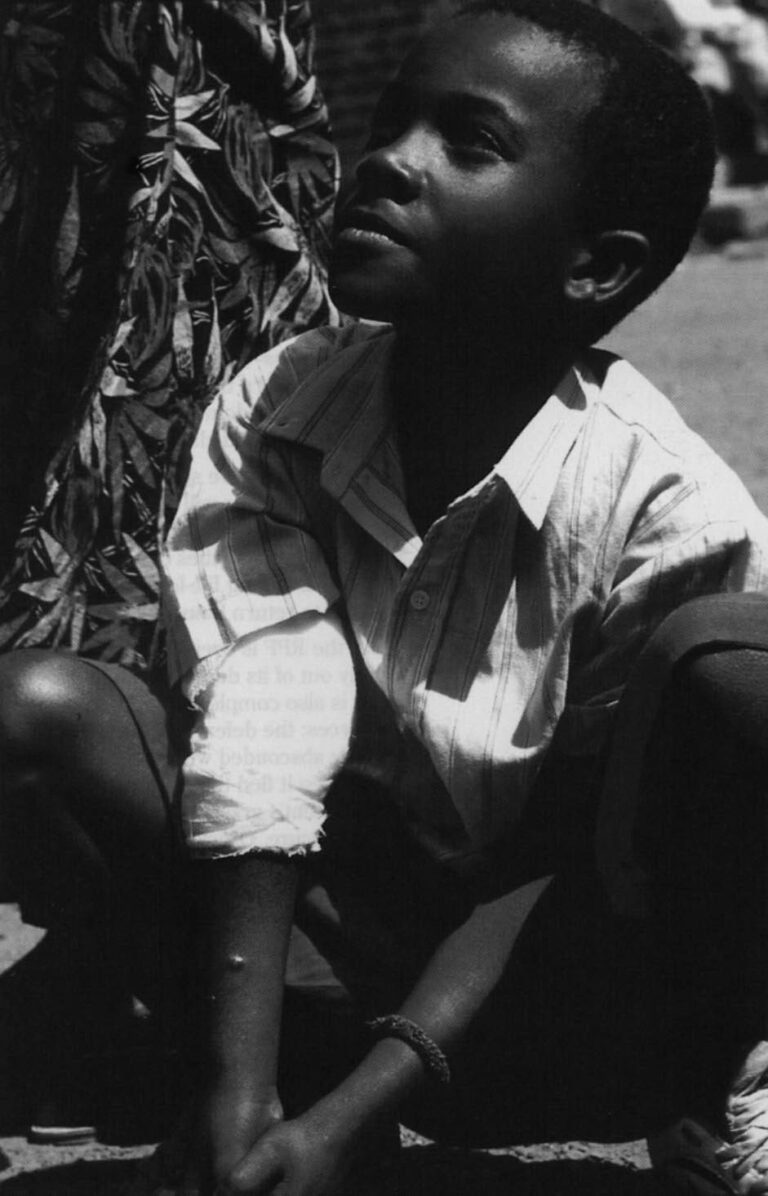

Sitting cross-legged on a wooden bench in an abandoned school tucked amid the steep mountain slopes of central Rwanda, 13-year-old Reveriani Rurangwa delicately runs a finger along the smooth, shiny scar that wraps around the side of his face from nose to ear. His ruined left eye is concealed behind a day-old bandage. What remains of his left arm is wrapped in gauze. In a voice that barely rises above a whisper, Reveriani recalls the spring day in 1994 when Red Cross workers pulled him from a pile of corpses that included his mother, his father, his brothers and sisters, and several hundred friends and neighbors.

“Perhaps they believed me to be dead,” he says of his attackers. “We were all inside the Catholic Church. There were so many there. We were attacked by the Interahamwe.” The Interahamwe were the state-sponsored death squads that shot, clubbed and hacked to death as many as half a million Rwandans last year, mostly ethnic Tutsis like Reveriani, in one of this century’s worst genocides. “They had grenades and guns, and they had machetes,” Reveriani remembers. The people inside the church were also armed, with bows and arrows, and machetes, but no guns, he says. “Only the Interahamwe had guns. The first time they attacked, we resisted. The second time also. But the third time they succeeded to massacre everyone with grenades.”

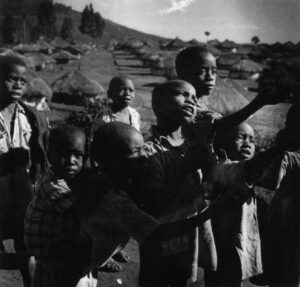

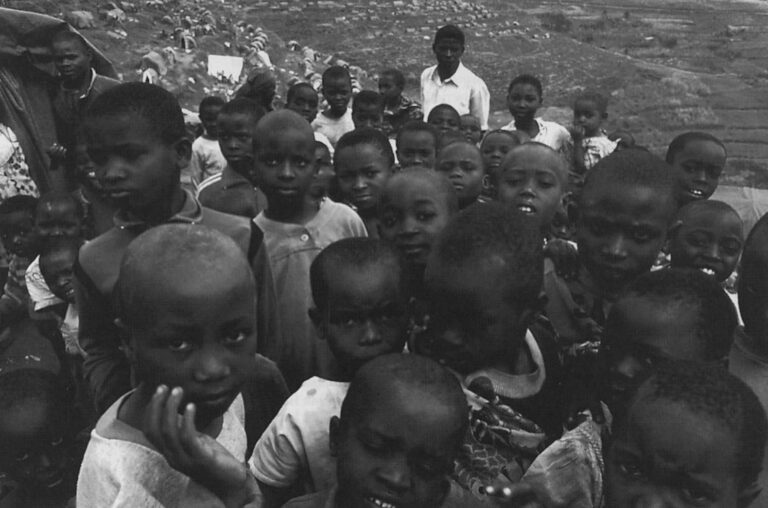

Like dozens and then hundreds and finally thousands of other children, Reveriani wound up at this former Catholic mission school in Nyamata, a dusty village on a winding dirt road south of Kigali, the Rwandan capital. Dazed and destitute, the children wander aimlessly amid the courtyards and classrooms nearby — tense with hunger, wracked by dysentery, malaria, and respiratory infections, and haunted, as Reveriani clearly is, by the images in their minds of unspeakable horror.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates that up to 100,000 Rwandan children were orphaned, abandoned, or somehow lost amid the carnage that consumed their central African nation last spring, and in the biblical exodus of refugees into neighboring countries that followed. Scarred for life by a monstrous crime, displaced from their homes, many nursing hideous wounds inflicted by weapons as crude as axes and hammers — barely 15 percent of these children were known to be receiving any form of institutional care at the height of the chaos last August.

By now the luckiest among them have survived their physical wounds. UNICEF and other relief agencies have embarked on a long-range plan to reunite as many as possible with surviving relatives — in the best African tradition of extended families. Yet with their country still unstable and profoundly polarized, there is fear that many of these defenseless victims of war are destined to become the next generation of warriors — vessels of hatred, ready recruits for the armies and militias of a vengeful Rwandan future.

Romania and Cambodia are chilling precedents. The late Romanian President Nicolai Ceaucescu’s infamous Securitate secret police was composed largely of orphans; Cambodia’s genocidal Khmer Rouge recruited thousands of orphaned Cambodian refugees in neighboring Thailand. Whether Rwanda’s orphans follow a similar path will depend on many factors, but certainly their potential for hatred is there. Reveriani Rurungwa put it this way: “I used to have Hutu friends, but I cannot be friends with them now because they have killed all of my family.”

“There is a lot of potential for violence in grief and trauma,” says Dr. Magne Raundalen, a Norwegian psychologist with long experience in Africa who visited Rwanda on behalf of UNICEF. “The basic emotion in a child is sadness,” he explains, “but long-term it can turn to hate and violence.”

Many of Rwanda’s orphans, like Reveriani, have seen their entire families slaughtered before their eyes. All have nightmares; many experience hallucinations. Others have possibly more complicated memories. These are the Hutu, children of the majority Hutu ethnic group that carried out the genocide. Many of these children have witnessed their own fathers and uncles and brothers participate in mass murder. Not a few, including some as young as 10-years-old, were lured into participating themselves.

Several hours’ drive west of Nyamata, seven-year-old Claudine Uwamahoro began her life as an orphan in August when first her father and then her mother dropped and died from cholera. They were two of the estimated 50,000 Hutu refugees who succumbed amid the wretched filth and chaos of the huge spontaneous settlements outside Goma, Zaire, where more than a million Hutu had fled after Rwanda’s Hutu-led government collapsed.

Claudine says her brother was killed by a Tutsi bomb. She says her father was a member of the Interahamwe.

Claudine stood barefoot on black lava, wearing a tattered red dress and carrying her baby sister, Yakaremye, on her back as she waited outside the cholera tent where her mother, Seraphine, 37-years-old, lay hollowed-eyed and emaciated, in the final throes of cholera. “I’m afraid she will die,” Claudine said matter-of-factly. “The sickness is very dangerous for her.”

Ten others had died in the tent the previous night. Nearby, a man solemnly wrapped the stiff frame of his newly-dead mother in a straw mat. He would deposit her on the roadside, to be picked up by French troops the following day. Relief workers rushed by Claudine carrying fresh victims on canvas stretchers. The stench of death from cholera and dysentery blended with the smoke of thousands of wood fires in this seething, desperate, makeshift refugee settlement of half a million Hutus, their lives in ruins, their leaders — and many of their husbands and fathers and brothers — accused of genocide.

In the midst of this nightmarish scene, on what would become the first day of the rest of her life as an orphan, Claudine was asked if she had any Tutsi friends. “I don’t love the Tutsi because they killed my brother,” Claudine replied.

Rwanda’s orphans were scattered from their homes after a still-unexplained plane crash on April 6, 1994 killed the country’s long-time Hutu strongman, President Juvenal Habyarimana. Immediately after the crash the Interahamwe militias, led by Habyarimana’s Presidential Guard, embarked on their systematic genocide.

Many of Rwanda’s orphans, like Reveriani, were left for dead amid piles of massacre victims. Others were abandoned or lost along the road because they couldn’t walk fast enough. Most were gathered up by good Samaritans or tagged along with the mass exodus of refugees. Some were picked up by the rebel Tutsi-led Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) in marshes and banana plantations.

The RPF captured Kigali in July, after a two-month siege. The rebel victory put an end to the genocide but triggered the massive exodus of Hutus across the border into Zaire. Many Hutus feared retribution for the genocide. The rebels for the most part adhered to their repeated pledges to refrain from summary revenge, but scattered reports of reprisal killings re-enforced an intensive propaganda campaign by Hutu leaders bent on preventing Hutus from returning to their homes.

In Kigali, meanwhile, the victorious rebels immediately formed a new government and appointed moderate Hutus as President and Prime Minister. Officials hope that most unaccompanied children can be reunited with surviving members of their extended families. The humanitarian agency Save the Children is spearheading an extensive tracing program modelled on the experience of Mozambique, where up to 80 percent of the orphans from that country’s decade-long civil war have been successfully reunited with relatives. Many Rwandan orphans have already been taken in by foster families –though relief workers express concern that foster children may be exploited as domestic servants, destined to be second-class citizens for life.

RPF officials have stressed that international adoptions will be promoted only as a last resort — a policy that reflects the special sensitivities of a rebel movement born among life-long refugees seeking to return home from exile.

But the RPF is overwhelmed and clearly out of its depth. The new government is also completely without resources: the defeated Hutu-led regime literally absconded with the national treasury when it fled the country. The new government’s grasp on power is by no means secure. Officials of the ousted Habyarimana regime have declared their intention to fight their way back into power, and they exercise considerable influence, coercive and otherwise, over the huge majority Hutu population that is currently displaced.

So Rwanda could well be at war for many years. It is in this fluid and ethnically-polarized environment that the orphans themselves provide a revealing — and troubling — window on their country’s predicament. Like all children, Rwanda’s orphans have absorbed the prejudices and stereotypes of their parents. These were compounded in Rwanda’s case by a bitter four-year civil war, and by the long campaign of racist propaganda, broadcast primarily on two government-backed radio stations that relentlessly demonized the Tutsis. For many orphans, Tutsi and Hutu alike, what they have witnessed this year has confirmed their worst suspicions about each other.

Reveriani, for instance, is matter of fact when asked why the Interahamwe attacked his family. “Because they want to exterminate the Tutsis,” he replies. “All the Hutus wanted to exterminate the Tutsis, because the Tutsis are friends of the Inyenzi and the Inkotanyi.”

Inyenzi means “cockroaches” — the term the Hutu-dominated government used to describe the rebels. The Inkotanyi was the militia of a 19th century Tutsi feudal king who bludgeoned the majority Hutus into submission. The term Inkotanyi was widely used during the war by Hutu propagandists to link the Tutsi-led RPF in the minds of Hutus with memories of past Tutsi oppression. It is a measure of the potency of Hutu propaganda that even Tutsi children like Reveriani have adopted such terms into their own vocabulary.

The views of newly-orphaned Hutus are just as disturbing. “Both my father and my mother were shot,” says 12-year-old Rukina, a sad-eyed new arrival at the huge make-shift Ndosho orphanage outside Goma, Zaire. “They were shot because the RPF soldiers are mean,” he explains. “The RPF killed children and women.” Asked why the RPF did such things, Rukina replies, “The objective of the RPF soldiers, when they killed everybody, was to take power in Kigali for themselves and for the Tutsi. The RPF soldiers, when they came, they killed Hutu only.”

Emmanuel Habizomona, an 11-year-old Hutu newly arrived at Ndosho, says his father was killed when the RPF bombed Kigali in April. His mother died after delivering a baby while trying to flee the country. Asked why all this has happened, Emmanuel replies, “The Inkotanyi wanted to kill us for to take the country. They are the Tutsis. They want to go into the country and to chase all the Hutus.” How does Emmanuel know this? “I heard this at school,” he replies.

Does Emmanuel hate Tutsis? “Please,” he replies, “see where I am.” Could he be friends with Tutsis if he returns home to Kigali? “If we got a chance to go home, we would not have the spirit to live again with the Tutsis.”

Rwanda’s minority Tutsis, traditionally cattle herders who comprised barely 15 percent of the population before the killing started, lorded over the Hutus for centuries in a feudal order that was adopted and exacerbated by Belgian colonizers enamored of anthropological theories about racial hierarchy. The Belgians introduced racially-classified identity cards that chillingly survive to this day: the Tutsis’ pale green ID cards figured like yellow Stars of David at the Interahamwe roadblocks.

The Hutus had been on top since 1959, when Hutu rebels killed thousands of Tutsis and drove tens of thousands more into exile. Nevertheless, Tutsis and Hutus share a common language and culture, and they have intermarried to such an extent that physical differences between them have blurred. The RPF launched its incursion in 1990 not to reimpose Tutsi domination, its leaders said, but to create a pluralistic democracy, reestablish the rule of law, and allow for the return of Tutsi refugees from exile.

But memories of oppression had been passed down from one generation to the next, and Hutu government propagandists made sure that the lessons were not forgotten. The RPF’s own sometimes indiscriminate tactics in the war merely reinforced the message.

Interviews with Hutu orphans make clear how extensively Hutu propaganda has influenced perceptions of the conflict –particularly in their understanding of the plane crash that sparked the genocide. Fifteen-year-old Josine Uwamahoro, for example, says both her parents were killed by the RPF. Asked why her parents were killed, Josine replies, “My parents died because Tutsi killed the President and Hutu came to revenge, and then they killed each other.”

In fact, there is no evidence that the RPF shot down President Habyarimana’s plane. Most independent observers believe that extremists within Habyarimana’s own ruling circle shot him down to preempt a peace agreement that would have weakened their hold on power. But the government-controlled radio immediately blamed the plane crash on the RPF, and urged Hutus to take their revenge on the Tutsis. Asked how she knew that Tutsis killed the President, Josine replies, “I heard it only. I was with other persons who said the Tutsis killed the President, so they must die. I heard it from many people.”

Has Josine heard about the Interahamwe? “The Interahamwe are young Hutus who are organized to kill Tutsis in the village,” she says. Is she aware that the Interahamwe killed many Tutsis? “The Inkotanyi killed many, but the Interahamwe small,” she replies. Asked why has all this has happened, Josine responds by articulating the relentlessly repeated propaganda line that the RPF was bent on capturing the country for the Tutsis and reimposing the old feudal regime. “The Hutu don’t want to be dominated, that is why. The Tutsi can never dominate the Hutu because the Hutu can never agree to that.”

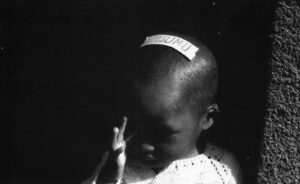

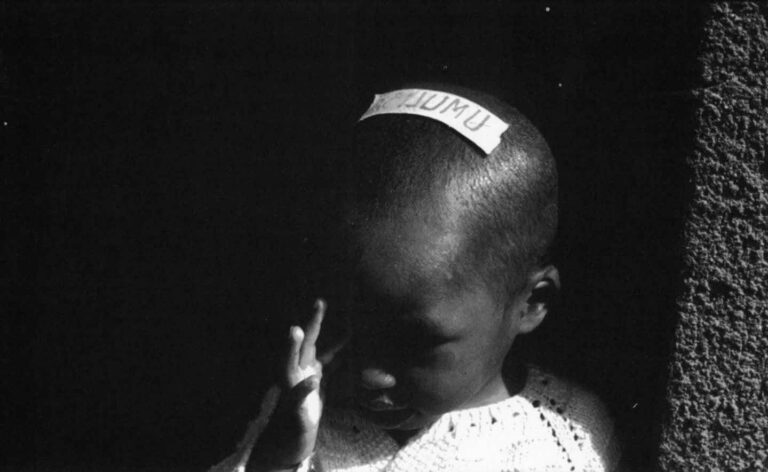

At the huge Kibumba refugee settlement outside Goma, 13-year-old Umumararungu says her parents died “because the Inyenzi want to take the country and dominate the Hutu.” How does she know this? “I heard that. Everybody said that.” Does she know that many Tutsis also were killed? “I know that Tutsi were killed by the Hutu, but it was a small number” she says.

In addition to her parents, Umumarungu’s older sister and her baby brother also were killed. “Because the Tutsis killed my parents, I can never love them,” Umumarungu says, “but if a Tutsi does something that is a good thing for me, I can like him. But Tutsis are dangerous.”

Umumarungu’s six-year-old sister, Umutetsi, sits on the ground by her side, wearing only a filthy sweatshirt, staring vacantly, her bare feet and legs straight out in front of her. “I don’t miss my parents because they have died,” Umutetsi says in a voice that is barely audible. Asked who killed her parents, Umutetsi replies, “Inyenzi.” And who are they? “Inyenzi means Tutsi. The Tutsi are bad.”

Nine-year-old Bayingana agrees with his sister. “People said the Tutsi wanted to take the country and then they would kill the Hutu,” Bayingana says, emphasizing that he has no Tutsi friends. “I don’t like the Tutsi because they kill people,” he explains.

His older sister, Umumararungu, adds, “We saw many people die from cholera and we were very furious. Because people have died and if they should be in Rwanda they would not have died. ” Then why won’t they go back to Rwanda? “But we cannot go home because Inyenzi are there and they can kill us.”

Jean Hakizamungu, 14-years-old, a former houseboy in Kigali who walked through the bush for 30 days after his parents were killed by the RPF, makes it clear that if his worst fears have been confirmed in the recent conflict, those fears were originally planted in his mind by his parents. “When I played football I played with Tutsis,” Jean concedes. “But I didn’t have a Tutsi friend because my father told me, ‘My son, be careful with Tutsis.’ My father said, ‘Because in history, the Tutsi and Hutu were not friends.’ He said, ‘In history the Tutsi and Hutu make fights.'”

These are sentiments that militia leaders of the future can exploit. And in Rwanda such a future may come sooner rather than later. In many of Africa’s wars, notably in neighboring Uganda, children as young as ten have been recruited as guerrilla fighters.

Can anything positive come out of this nightmare? Magne Raundelen, the Norwegian psychologist, noted that victims who are helped by others often become helpers themselves. “Kindness and responsibility in the helping process is tremendously important because these kids are hungry for it,” he says.

He is talking about men and women like Father Percy Simonsa, a Belgian Catholic priest who gathered more than a hundred Tutsi orphans, many of them disabled, and led them on a night-time trek through the bush — three kilometers a night for three nights — to the safety of RPF-held territory.

By August, Father Simonsa had taken up residence at the Nyamata center for unaccompanied children. He spends much of his time simply listening as his charges tell one harrowing story after another. Then he interrupts them to ask: “But what have we learned that is positive from this experience?”

Ten-year-old Joseph Ngoga has lost his entire family in yet another church massacre by the Interahamwe. A hideous four-inch scar mars Joseph’s sad little face; a machete has shattered his jaw. Like Riveriani, Joseph was rescued from a pile of more than 20 relatives. “They believed I was already dead,” Joseph says in a voice so faint it is almost inaudible. “I do not think about it,” he adds, unconvincingly.

Father Simonsa presses Joseph to think of something positive. It appears the priest has been pressing this theme for some time, and Joseph is ready with an answer.

“The positive thing I have seen,” Joseph says. “is that some people tried to hide me and protect me and give me food. And they told me to be very very careful so I won’t be seen.” Father Simonsa asks, who were these people? Joseph doesn’t know. But he remembers one thing about them: “They were Hutu,” he says. And what has he learned from this? Father Simonsa asks. “I have learned,” Joseph replies, “that there are Hutus who are bad and there are Hutus who are good.”

@1995 Bill Berkeley

Bill Berkeley is a freelance writer in New York City who has been reporting on African on his Patterson fellowship.