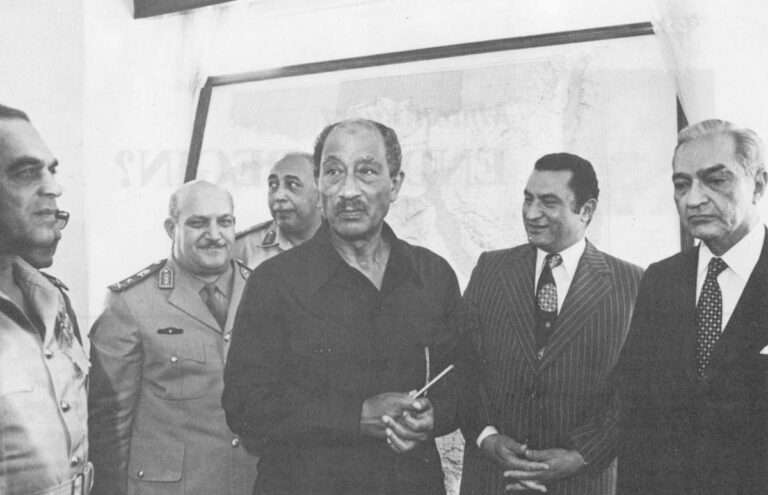

CAIRO – Hassan AI-Tuhami is one of those men who, at first sight, conveys to you a special presence, and even something more. I had asked for an interview because he is known as Anwar Sadat’s eminence grise, and apart from Sadat himself is considered the principal inspiration behind Egypt’s peace overture to Israel. He invited me to see him late one afternoon in his apartment in Zamalek, the most bourgeois of the quarters of Cairo. I arrived only with the knowledge that he was regarded as a man of mystery, and nothing more.

A servant showed me into his large, sparely furnished living room, and I sat down to wait on a once-stylish, now threadbare sofa. After a few minutes, a jockey-sized man in foppish dress entered and sat down on a chair near me. He talked about Arabian race horses, and I said to myself, ‘Is this the character I came to see?’ I promptly revealed my uncertainty by a silly question, to which the man answered reverentially, ‘You’ll have to ask His Excellency’. Several minutes later, His Excellency burst through the door, a man of medium height with a barrel chest and strong arms, wearing an excellently cut black suit, an expensive white shirt with French cuffs and a black tie. He had neatly trimmed grey hair, a short beard and the piercing eyes of a mystic. It struck me at once as appropriate that he should be known as the ‘Rasputin of Egypt’, and in the ensuing two hours I spent with him I experienced nothing which persuaded me that he was, indeed, an ordinary man.

Even now I am not sure what to make of the meeting, or of Al-Tuhami. He was stern and unsmiling, but not unfriendly. He was obviously accustomed to deference, but he courteously poured tea for his friend and me. He possesses the title of Deputy Prime Minister in the Presidency, but when I suggested that he did not have the air of a public official, much less of a bureaucrat, he laughed and said I did not look much like a journalist either. We talked of events with which I was reasonably familiar, but he gave accounts which were fundamentally different from what I had heard before, and which threw a dramatically different light on some key events in recent history. He spoke with ardor, even zealotry, but yet he conveyed great credibility to me. At the least, I must say that I cannot dismiss what he told me.

Al-Tuhami talked first of his secret contacts with Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan in Morocco in the months preceeding Sadat’s trip to Jerusalem in November of 1977. That the two men met is now well known but AI-Tuhami made points to me that seem to give a different interpretation to what has heretofore been published. He said the initial meeting was in the spring of 1977, significantly earlier than the September encounter of which Dayan has spoken. More important, he challenged Dayan’s contention that the talks in which the two men engaged were no more than explanatory, and were limited to a settlement in the Sinai.

“Dayan came with two Israeli witnesses and seven security men”, AI-Tuhami said, speaking of their culminating meeting. “He read from a paper, which he held in his hand. He had instructions from Begin. He was not inventing. He was very clearly speaking for the Prime Minister.

“Dayan admitted all our rights in the occupied land, including Jerusalem.

“He agreed to a confederation between the West Bank and Jordan. He said he did not want PLO representation in any government on the West Bank, and he wanted no Palestinian state. He trusted Jordan, and he wanted Jordanian safeguards.

That’s why Jordan was ultimately included in the Camp David agreement as responsible in the negotiations for the West Bank.

“There was also an agreement that Arab Jerusalem would be an Islamic Vatican. At first a Jordanian flag would fly over it. Then Jerusalem would establish its own municipal government, though there would be a joint board of supervisors with West Jerusalem, to handle municipal problems. But Arab Jerusalem would be constituted as an independent state, with open borders with Israeli Jerusalem.

“Begin agreed to all of this in the mouth of Dayan. It is true that these were not negotiations. Dayan didn’t lie when he said later that these were not negotiations. But these were clear statements of the intentions of both sides. The check we had to pay in return was peace, and we agreed to that willingly. All that remained was to find a formula to implement the agreement. If people had kept their word as honest politicians, it would have been a fixed commitment, and we would now have a final peace”.

AI-Tuhami said the agreement he reached with Dayan in Morocco fell victim to inner government intrigue in Jerusalem. Whenever he spoke of Begin during our conversation, he gritted his teeth visibly, but his anger was directed less at what he saw as duplicity than as weakness. “The old terrorists took Begin on and defeated him,” AI-Tuhami said, referring to Begin’s confederates from the days of the underground struggles for Israel’s independence. Some of them are the hard-liners who remain Begin’s associates today. It was with an awareness of the bitter debate going on within the Israeli cabinet that Sadat, at his urging, decided to go to Jerusalem, Al-Tuhami said.

Al-Tuhami told me that, from the start in Morocco, Dayan had insisted that Begin wanted to meet Sadat personally in the interests of peace. He said he replied to Dayan that such a meeting was out of the question, until all the problems between the two states were resolved. Then, with the Moroccan initiative in peril, he persuaded Sadat to change his mind. “Sadat was ready to confront the whole world with the prospect of peace”, Al-Tuhami said. “He wanted to cut short all steps, and find a solution once and for all”. Begin had not the slightest hint of the Jerusalem visit, Al-Tuhami said, before Sadat made the decision and was ready to leave.

It was at this point in our conversation that Al-Tuhami rose abruptly and said, “Excuse me, I have to pray at sunset”. With that, his friend also stood up and, without self-consciousness, the two men unfolded prayer rugs, simple swatches of heavy cloth about three by five feet, and laid them on the floor, pointing east. Shoulder to shoulder, the two men took off their shoes and dropped to their knees and, while his friend remained silent, Al-Tuhami recited prayers.

After five minutes or so, the friend got up and returned to his chair. Al-Tuhami continued, bending with great dignity to touch his forehead to the floor, his prayerful whispers broken only occasionally by guttural sounds emanating deep in the throat. Again and again, he brought his bulk lithely to a standing position before dropping back to his knees. He prayed for ten minutes. Then, with no ado, he resumed his seat next to me.

Settling back into the conversation, Al-Tuhami told me of an episode that occured the morning after he arrived in Jerusalem with Sadat in November 1977. He said he received a caller in his room at the King David Hotel, at the very moment that Sadat was preparing to leave for the Knesset, to proclaim his historic peace offer. Al-Tuhami refused to tell me the caller’s name, though I pressed the point as hard as I could. He said only that the man was known to him as someone from the “inner government of Mr. Begin, from his political bureau”. The man announced that he had been instructed, Al-Tuhami said, to convey a message in his official capacity. The message was that he, Al-Tuhami, should go to Sadat and tell him to pack up his bags and leave Jerusalem at once.

I confess to having been at a loss to interpret this rather crucial item of information, and I still am. Al-Tuhami took it as a signal of the bitterness that divided the Israeli cabinet, and of the political struggle that was going on, even at that moment. He did not claim that the messenger came with Begin’s endorsement, or even with Begin’s knowledge, but he was sure that the message tolled the death knell of the peace process, without its ever really getting underway. In retrospect, Al-Tuhami said, it is clear that the dominating force within the Israeli cabinet looked upon Sadat’s visit as a threat. At most, this dominant force wanted peace only with Egypt, and had no sympathy whatever with Sadat’s vision of a settlement that would lead to peace with the entire Arab world.

Al-Tuhami said, after the messenger left, he worried for a moment that Sadat faced genuine danger in Jerusalem, but he said he did not tell Sadat of the message until after they returned home to Egypt. Sadat had invested far too much in the journey, and he himself, he said, had no intention of taking orders from a messenger to pack up and leave.

At Camp David, nearly a year later, the United States tried and failed to salvage the peace process, Al-Tuhami said. He said he personally warned President Carter that unless the questions of importance to the entire Arab world, including Jerusalem, were resolved “the whole area will erupt against you”. He said Saudi Arabia told Carter explicitly that it would support any settlement that included Jerusalem and the Palestinians, but Carter was satisfied with the half-measure of an exchange of letters between Begin and Sadat on the most sensitive issues. The United States miscalculated completely in believing that Jordan and Saudi Arabia would join in the procedures initiated at Camp David, Al-Tuhami said, and when Secretary of State Vance failed to win them, everything went wrong.

“It was ridiculous”, Al-Tuhami said. “Begin said he was not authorized to speak about Jerusalem. That must mean he’s not a prime minister. Begin knew an agreement could get the support of the major Arab countries if the Palestinians and Jerusalem questions were settled. Instead, he did exactly the opposite, to isolate Egypt from the Arabs, and the American administration yielded to his pressure.

“Carter’s biggest mistake was in adopting a posture of optimism about the future, since now the United States will be blamed whenever the process collapses. Sadat nearly walked out of the conference, and remained only because Carter begged him to stay. But the Americans really failed us.”

Al-Tuhami was not optimistic in talking to me about the prospects for salvaging the peace process. He said that until now Sadat has served as the vanguard for the Israeli government, protecting Begin from the wrath and anxiety that will arise around the world when it becomes clear that the negotiations are dead. Sadat, by continuing bilateral talks in the absence of any Israeli concessions, has enabled Begin to evade responsibility, he said, but time is running out. By the time America wakes up, Al-Tuhami said, the limit may already have passed.

Al-Tuhami estimated that the two sides might still have as much as a year to reach a solution. But he expressed severe doubts that Begin is the man chosen by fate to make peace. He said the Israeli prime minister should be known as “Mr. End” rather than “Mr. Begin”, and he so pleased by his pun that he repeated it several times.

Conditions are changing drastically, Al-Tuhami said, with the Middle East threatening once again to become an arena of conflict between the great powers. “For six months there have been no negotiations”, he said. “We have been living in a honey dream. We have had only flirting between the two heads of state”. A year from now will probably be too late for a settlement, Al-Tuhami said, and the decisions will no longer be in the hands of Begin and Sadat.

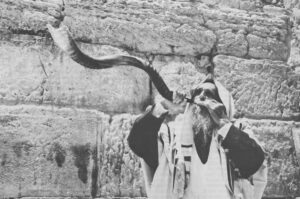

It was at this point, as I look back on my notes, that Al-Tuhami’s talk seemed to turn from the political to the mystical. I remember feeling that he suddenly began to address me not as a journalist but as if I shared with him some holy mission to bring peace between the Moslems and the Jews. “Tell your rabbis all over Europe”, he said, “tell your people, have the honesty to tell them the truth”. I was unsure now who he thought I was, but I promised to write his message honestly.

“We have given Israel a chance to live in peace”, he said, his voice trembling with conviction. “This is the last test from God, whether the Jews live unscattered in the world.

“People don’t know why I urged Sadat to go to Jerusalem. It was nothing that I thought we had an agreement with Dayan, compared to what I feel. The Bible says something about the Jews beating their swords into plowshares. That is their destiny, and I was anxious to save the Jews. We are giving them this chance, and if they are not smart enough to take it, they’ll lose it.

“This is the first time I have said that to anyone. But this is my intuition of what lies in the future”.

©1980 Milton Viorst

Milton Viorst’s Fellowship project is Zionist and Islamic Ideas in the Mideast Crisis.