In an upcoming NBC television movie, a black youth from Harlem graduates from Phillips Exeter Academy with honors. Three weeks later, he is shot to death by an undercover police officer who alleges the young man tried to rob him.

The film is based loosely on the life of Edmund Evans Perry, one of hundreds of disadvantaged minority youths who have attended preparatory schools through the national minority talent search agency, A Better Chance, Inc.(ABC).

Another theatrical account based on Perry’s life is “No Laughing Matter,” an upbeat amateur musical performed before ABC students currently enrolled in prep schools. But this version has a happy ending. In it, a black youth from inner city America triumphs over the angst, insecurity and ostracism of going to boarding school and returning home.

Both pieces mirror the real pressures ABC students face. Many find themselves straddling two worlds, galaxies apart: One white, opulent and often inhospitable; the other black, needy, and home. Some students negotiate the social chasm with ease. Like an astronaut unburdened by gravity, they float from the planet of tenements and graffiti to the universe of ivy halls and halcyon hills and back again.

For others, the path from projects to prep is a clumsy, broad jump weighted with culture shock, shame, academic disappointment, loneliness, identity crisis, and loss of confidence. They find that severe struggles are crucial for happy endings.

“The play was too real for me,” said Tiffany Hicks, an ABC student from New York City who attends the Millbrook School. “People at my school just don’t understand that at home, I am under pressure to get down with drugs. And my friends at home have the attitude ‘What are you going to that school for? It is the white man’s community. You belong here with us. You don’t belong there.’

“I have to sort of balance it all,” said Hicks, 15. “It’s like I’m on a scale: Got to go to Millbrook; got to go home; got to go to Millbrook. I am constantly trying to fit in.”

Hicks and 29 other ABC students interviewed at five prep schools agree that the jump would be a lot smoother if ABC provided students with more academic, emotional and social support once they have been placed in schools.

“I feel like ABC just brought me to this school and left me,” said Millbrook senior Jennifer Peavey, who is from a Brooklyn family of eight. “There’s no follow-up. They don’t keep any kind of communication with us once we get to the schools. Many times I would have preferred to have gone home. I don’t know why I stay here.”

With three older brothers who were accepted to M.I.T. from New York City public schools, Peavey questioned the benefit of taking the ABC ticket.

“When I came to this school I was one of four black students,” Peavey said. “That was an extremely hard jump from being one of 3,000 black students in junior

high school. There is no institutionalized support for students who come to the school. You either have to lose your identity and be a simple milk dud or you are not accepted.”

ABC President Judith Berry Griffin, who oversees the student selection process at ABC headquarters in Boston, sympathizes with students like Peavey but believes most possess the emotional stamina to make it on their own.

“ABC kids are not broke so they don’t need fixing with special remedial academic or social programs to prepare them for prep school,” Griffin said in an interview. “We cannot go to the schools and hold their hands through this experience. They have to go out there and do it on their own. We can’t guarantee that it won’t hurt, but it will be worth it in the long run.”

Griffen added, “The support issue raises valid points that ABC has had to face. But with our children in more than 150 schools, realistically how can we provide support? It’s cost prohibitive.”

ABC functions primarily as a placement service, scouting about 300 academically talented youths each year. They are chosen from more than 2,000 applicants who are evaluated by grades, extra-curricular activities, teacher recommendations, in-depth interviews, essay-writing ability and Secondary School Admissions Test (SSAT) scores.

Once students are placed, ABC’s Student support director and regional coordinators loosely monitor students’ academic progress, stepping in when difficulties surface. The coordinators, located in large metropolitan areas like New York City, communicate with students’ parents and plan social activities for youths during Christmas and summer vacation. ABC also sponsors summer enrichment such as a business program.

At each school, ABC designates a teacher as the ABC representative to assist students. But many students say they are uncomfortable with these teachers, who usually are white and often ignorant of pressures ABC students face.

One expert on black child development familiar with ABC and the Edmund Perry case said hands-on support is crucial.

“Generally speaking, if proper support isn’t provided, you are asking for trouble and you are asking for failure,” said Dr. Alvin Poussaint, Harvard University Medical School associate professor of psychiatry. “It’s not just a question of students graduating. It’s a question of support and orientation that gives them the chance to maximize their potential.

“One of the realities for Perry and a lot of these kids, and it was for me in the 1950s as a student from Harlem attending all-white Stuyvesant High School, (is) they have to be conscious that they are living in two worlds,” Poussaint said.

In the interviews, ABC Students listed the living-in-two-worlds syndrome and academic difficulty as major hurdles. Also high on their list of struggles was adjusting to a predominantly white and wealthy milieu, culture and language barriers, and an absence of black teachers or other black adults.

Silhouetted by Avon Mountain in Simsbury, Connecticut, the Ethel Walker School for Girls stretches over 620 acres crisscrossed by horse trails and dotted with impressive buildings. Actress Sigourney Weaver is among its alumnae. Farther west in Lakeville, the Hotchkiss School stands like a gated fortress on a remote ridge of the Berkshire Hills. Poet Archibald MacLeish and Supreme Court justice nominee Robert Bork are its prized alumni.

Both institutions are typical of the new world ABC students meet: WASPy and wealthy.

“When I first came here I saw everyone driving Jaguars and Benzes,” said Kisha Mair, 18. “My family came driving a little rickety-rack car with a rope tied on the back. After a while I noticed that I didn’t really have anything compared to these people.”

Mair, raised in Brooklyn, has taken three painful years to master the art of living in two worlds.

“I have a dual personality now–I have to be two different people when I come here and when I go home,” said Mair during a lunch break in the high-ceiling dining hall.

“When I’m at home I have to think and do things the way my family does: I have to speak Jamaican patois,” said Mair. “When I’m in the streets with my friends I have to speak black English–double negatives. When I come here I have to speak proper English, get my verb tenses in order. I felt the hardest thing was to get my personalities straight and my language in order.”

But Mair has triumphed and is now one of Walker’s most distinguished seniors: a High Honor Roll student, recipient of the Harvard-Radcliffe Book Award, the R.P.I. medal for mathematics/science, senior class president and senate president.

Some ABCers find themselves trying too hard to fit in with the L.L. Bean and docksiders set. For them, the trip home is a painful journey.

“I had this problem last year: I really thought that I was going to totally lose my identity,” said LaDawn Lanier, another Walker student from Brooklyn.

“I was trying to fit in so much that I started to act like everybody but myself–I started to forget who I was and where I came from,” said Lanier. “When I went home, my brother and sister would tell me to go back to school with my white friends and go shopping with them. They didn’t want to be around me.”

Other students are burdened by the ethnic indifference and ignorance of their WASP classmates.

Said Alexis Bryant, a Hotchkiss senior who describes herself as from a “high low class family” in Gary, Indiana: “If I had to do this all over again, I wouldn’t. I would have just stayed home. It’s too hard because at the same time I’m a student I have to be a teacher to people who don’t know anything about people who are different from them.

“If you come here and you aren’t a strong person your mind is going to be messed up,” said Bryant, a tall girl with a serious gaze.

One student who asked not to be identified said that school officials referred her to a psychologist when she complained about racially intolerant classmates.

A bitter surprise for many low-income ABC students is the coldness they encounter from black preppies whose parents can afford to pay the hefty tuition.

“It troubles me a lot when I see black people who don’t associate with blacks like me,” said Darren Campbell, a Hotchkiss junior from Southside Chicago. “Even though they have grown up in Greenwich, Connecticut, or wherever–no matter what status we are, we cannot ignore each other because no matter how wealthy you are as a black person or successful, you are always a “n…..” in some people’s eyes.”

Social discomfort is compounded by academic difficulty. With 150 students, Walker’s largest classes have 12 students, the smallest two or three.

At first, Connie Morales, a petite Puerto Rican from the Bronx whose flip hairdo and horn-rimmed glasses give her a preppy look, found the school work intimidating. She came to Walker from Manhattan School of Science. Once at the top of her public school class, Morales endured a jarring fall from glory and a bruised ego when first semester grades plunged to D.

“I was used to getting 80s and 90s, but when I came here I got a D in science for the first time in my life,” said Morales. “Here I have to work for my grades. It’s no longer kick back and I will get a 90. It’s hit those books and you’re lucky if you get an A.

“I saw freshmen who had come from other private schools and they got straight As,” she said. “I was a sophomore struggling to get a C. I wondered why wasn’t I granted this privilege? Why did I have to struggle so hard when it seemed like they’re just given everything, including a good education from the start?”

Now a junior, her grades have risen to solid B. She joins the ranks of ABC students at Walker who are academic stars. Five out of 11 were on honor roll in 1990. Four were recipients of the Harvard-Radcliffe, Brown, Dartmouth and Smith College book awards. ABC students currently are presidents of the sophomore, junior and senior classes.

“They are disproportionately represented on our honor roll and in student leadership,” said Paula Chu-Richardson, Walker academic dean. “It seems to me that a lot of them are survivors by definition. They rise to the occasion.”

“As far as academics go I think ABC can offer assistance,” said Campbell at Hotchkiss. “As far as the social adjustment goes, there’s nothing anyone can do for you. You just have to figure it out for yourself.”

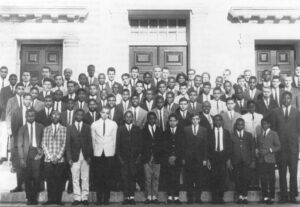

Once, ABC helped students do that figuring. In fact, Project ABC’s original mission was to bridge the gulf between prep school and housing projects. In 1964, it began as an intensive eight-week academic and social orientation program at Dartmouth College. Included were lectures on coping in the white man’s world. Successful participants won scholarships to prep school.

When federal funds petered out in the mid-1970s, so did the summer programs. Today’s recruits receive no such in-depth preparation. Instead, local ABC sponsors such as the Urban League invite prospective students to one-day sessions of speeches, alumni panels, Q&A and guidance.

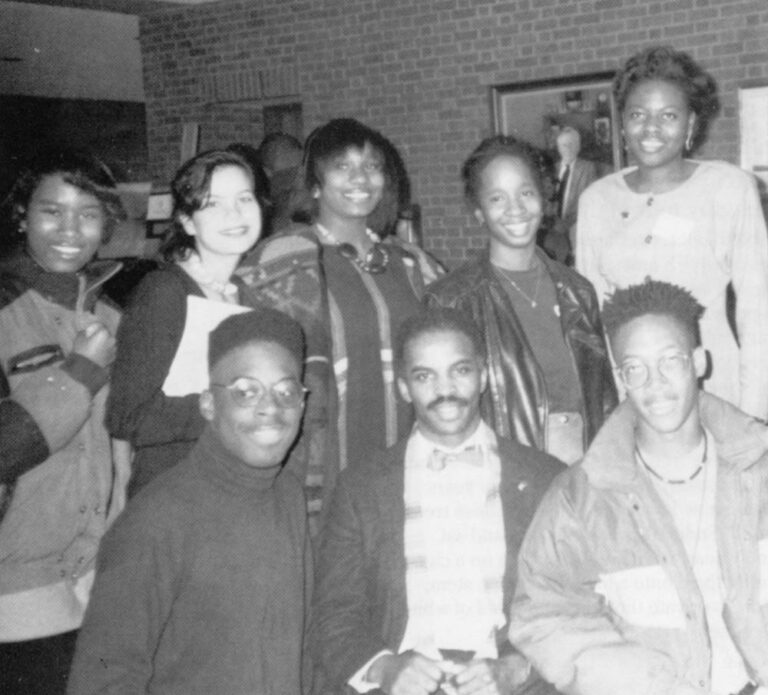

Last August, however, ABC, concerned about requests for more preparation sponsored a three-day orientation at Marymount College for incoming New York and New Jersey students. It was the first in more than a decade.

During an alumni panel, Marmaduke Johnson, a recent Northfield Mt. Hermon graduate who wore dread locks, warned prospective students, “Don’t become like Chip and Muffy. You have to hold on to your own identity.” ABC staff equipped students with a 1-800 “hotline” number to dial day or night, in case of academic or social emergency.

But some ABC alumni who now work for placement agencies modeled after ABC say that three days of orientation for three-to-four years of private school is a reckless ratio of preparation.

“A program has a basic responsibility once it places the student in a school. There should be some kind of follow-up because every student does not have the ability to punch it out so to speak,” said Janice Peters, a counselor with Prep for Prep, a 13-year-old New York City-based placement program.

“Those who are not able can perhaps learn with guidance, rather than just dumping them,” said Peters, who attended Milton Academy in the late 1960s, among the first ABC students.” I think a lot of folks do get lost by the wayside.” After experiencing three years of “emotional numbness” at Milton, even with orientation, Peters said she feels compelled to aid future generations of black preppies.

“We start recruiting kids in the fifth and sixth grade to prepare them to go to prep schools in the eight and ninth grades,” she said.

Prep for Prep currently has 300 students. All are required to complete a 14-month preparatory program that includes evening and Saturday classes (often the norm at prep school), summer courses and cultural activities.

Prep for Prep assigns each student a counselor who closely monitors academic and social progress and serves as liaison between parents and the school. “We can find tutors, talk to parents who don’t understand the prep school bureaucracy or we can be a shoulder to cry on,” said Peters.

Five years ago, the Albert G. Oliver Program began in New York. Each year it places 60 new students in preparatory school. Oliver also scouts for academically talented but economically disadvantaged youths. They must take catch-up courses and work in summer. Further, 40 hours of community service each year is mandatory to insure that students develop a sense of commitment to their home communities.

Teachers and administrators at prep schools praise the backbone of support Oliver provides.

“The Oliver kids are hard to beat,” said Robert Oden, Hotchkiss headmaster where a mix of ABC, Prep for Prep and Oliver students walk the halls. “The Oliver representative is up here at least once a month if not more. There’s a real family feeling amongst the Oliver students.”

James Turner, the Oliver counselor who makes the rounds to Hotchkiss and other New England boarding schools, said: “I’m like a big brother to them.”

“I stop by to check their pulse. If a kid is having a problem, we’ll go have a pizza. That’s important to academics, seeing a familiar face. We are a piece of home. We don’t just stick them out here and say ‘See you in four years.’ We send them a card on their birthday. Sometimes the ABC kids sit right down and talk to me too if they are having a hard time.”

Still Peters and Turner praise ABC as a trailblazer despite its limited student support.

“ABC was the first. It’s a huge national operation, they are helping so many more kids than we are,” said Turner. “So it’s harder for ABC to provide the support that we do. But a lot of those ABC kids are strong. They pick them that way.”

Members of the ABC New York Parents Association, while praising the superior education their children receive, worry that the ABC experience can tax the psyche of youths already imperiled by adolescence.

“I’m concerned about their mental health,” said Marva Phillips, a Queens mother who has sent three of her six children to Choate, Northfield Mt. Hermon, and Promfret through ABC. “They are already so vulnerable when they go away. And often the parents are too intimidated to deal with the schools, and have no idea what they are going through.”

ABC President Griffin contends that private schools, their rarefied ambience far removed from poverty and need, must take more responsibility for easing the social and academic transition.

Some schools are committing time and money to that end. In 1989, Choate Rosemary Hall hired a black former school principal to coordinate multicultural activities. At Hawken, a private day school outside Cleveland, administrators recently agreed to hire a team of Gestalt Institute psychologists to sensitize faculty in dealing with “non-traditional” students.

In February, Millbrook hosted “Celebrating Diversity” weekend. In addition, Millbrook is desperately seeking minority teachers, said Clark M. Simms, an instructor. At present, the only minority is an Argentinean teacher. “We can’t get blacks to come to these isolated communities and take the low pay that independent schools offer,” said Simms.

At Hotchkiss, Groton, Promfret and other prep schools, some ABC alumni–the pioneer black preppies–have returned to smooth the way for future generations of minorities, particularly ABCers.

Curtis Spence, who was a foster child when ABC sent him to Cushing Academy in 1973, is now associate director of admissions at Hotchkiss. His prep school days were a roller coaster of academic ups, mostly downs and social maladjustment.

“When I was in prep school I didn’t have a black teacher I could go to for solace or to help me wade through things,” Spence said. “I came here so that these kids would have someone.”

As he walked the corridors, Spence sported an African kinte cloth bow tie. Pinned to his lapel were tiny replicas of the American and Black Nationalist flags.

“In everything I do here, I’m trying to help the kids bridge these two worlds in a way that forges a strong new identity that does not deny their blackness or culture,” he said.

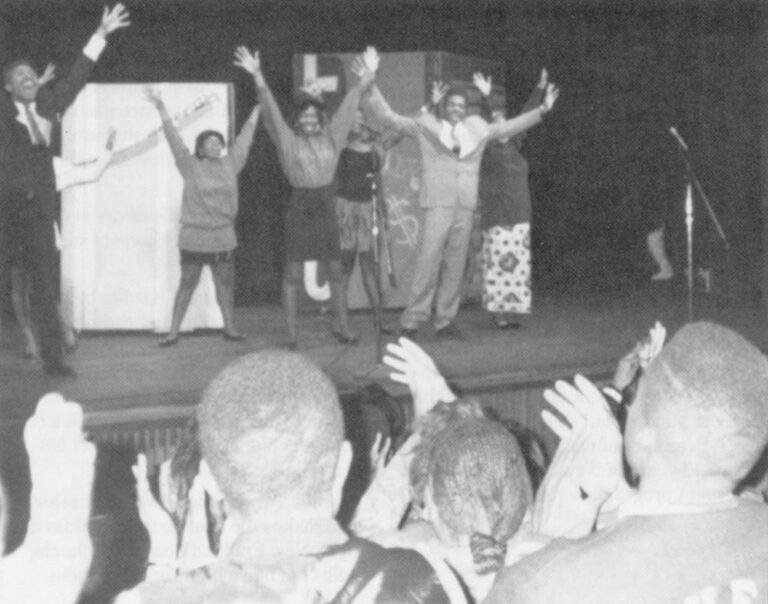

In December, Spence, with the blessing of Hotchkiss Headmaster Oden, hosted a weekend Kwanzaa celebration that drew more than 200 black preppies from surrounding schools. Scores of ABCers were among them.

Through speeches and poetry, they celebrated and commiserated being black and poor in prep school. Students donned African garb and festooned the dance hall with red, green and black balloons.

Entertainment was a split ticket: A rock n’ roll band played one hour and a rap deejay the next, the result of a compromise negotiated by ABCer Alexis Bryant, president of the black student association. The weekend highlight was a performance of “No Laughing Matter.”

©1991 Charlise Lyles

Charlise Lyles, a graduate of the ABC program, is examining its impact in the last 27 years. She is a reporter for the Virginian-Pilot and Ledger-Star.