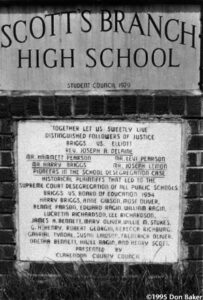

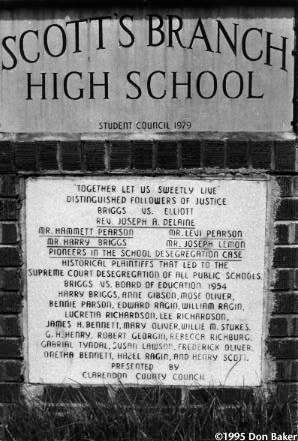

SUMMERTON, South Carolina – The orange-and-blue cover on the yearbook at Scott’s Branch High School here proclaims this sleepy Southern town as “the birth place of equal education,” but a look inside the town’s gleaming new $8 million school building belies that promise.

Scott’s Branch, which was the locus of the first law suit that successfully challenged segregated schools in the nation, is barely more integrated today than it was four decades ago, when the U. S. Supreme Court declared “separate but equal” schools unconstitutional.

Yes, the separate and unequal dual school systems that existed before the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education ruling are gone, but in their place is a unitary school district ceded to African-Americans by whites.

Of the 1,365 students enrolled in Clarendon District One, the official name of the junior-senior high school and two elementary schools here, just 16 are white, and most of them are in the lower grades. There are no white students in grades 10, 11 or 12.

The situation bestows prescience on former Summerton school board attorney S. Emory Rogers. He argued against the implementation of Brown before a federal judge in 1955, and predicted that, court order or no court order, integration wouldn’t occur here in Clarendon County until sometime in the 21st century.

More disturbing than the absence of whites in the classroom here, and in many other poor, majority-black school districts around the country, is the absence of learning.

Test scores and anecdotal evidence place the achievement of pupils here at or near the bottom of all schools in South Carolina. Scott’s Branch students who took the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) in 1994 posted the lowest average scores – 289 verbal and 353 math – of any of the 91 school districts in South Carolina, which in turn ranked last among the 23 states where the SAT is the primary testing vehicle for entrance to college.

Certainly, the fact that the district is one of the poorest in the state – four out of ten families fall below the poverty line and nine out of ten children qualify for free or reduced lunches – is a major contributor to the dismal test results.

Faced with such basic challenges, little energy is expended worrying about how to attract whites to the schools. Besides, so few remain in the area that there would be little integration if all of them suddenly had a change of heart and sent their children to Scott’s Branch.

Instead, the focus is on how to fix the schools. A start has been made under a new district superintendent and principal, who are replacing poorly trained and burned-out teachers; improving readiness for entering pupils who get little preparation at home, and strengthening the curriculum.

“Students can’t demonstrate what they haven’t been taught,” said State Superintendent of Education Barbara S. Nielsen, whose department has declared Clarendon One an “impaired” school district, one of only three in the state. The designation places it in a form of receivership under which the state monitors and assists it in trying to attain minimum standards. The state aid includes assigning master teachers to observe classroom instruction, strengthening a lame curriculum and arranging exchanges with successful schools in other parts of the state.

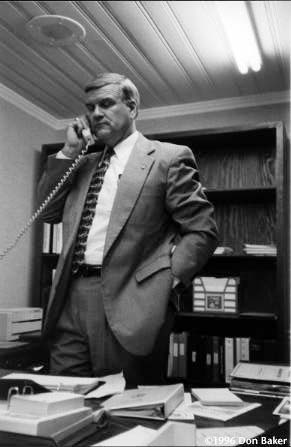

The district’s new superintendent, R. Jerry Leviner, said that over the years Scott’s Branch students have been allowed to “take the easy way out,” with course offerings that emphasized photography and industrial technology instead of algebra and literature.

To boost test scores, Leviner instituted a strategy popular in affluent districts – his staff is teaching to the test. He defends the tactic, which involves using computer software to accustom students to SAT-like quizzes, saying “they are learning more than beating the test. The program takes care of basic skills and beyond.”

Leviner was brought in with orders to clean house, which he is doing. Since his arrival in October,1994, he has replaced 21 of the system’s 90 teachers, including many who were not certified to teach the subjects to which they had been assigned.

Leviner also is cracking down on absenteeism, by students and faculty. He discovered that Scott’s Branch students had a better attendance record than their teachers, many of whom were treating unused sick days as vacation. To counter that, Leviner is offering bribes, in the form of $10 for each accumulated sick day.

Scott’s Branch also has a new principal, Joseph R. Singleton, who attacked another problem, discipline, by installing a metal detector at the door, along with a bucket that orders “deposit gum here.” However, so far he has refrained from using an electronic bull horn he inherited.

What may be more difficult to fix than discipline or dedication is a defeatist attitude that presumes these poor, black children can’t learn as well as their white, middle-class counterparts. It is a view not limited to subscribers to the “bell curve” theory that blacks are intellectually inferior.

“Most kids live up to our expectations of them,” said Luther W. Seabrook, director of curriculum and instruction for the South Carolina department of education. Seabrook contends that demanding schools can compensate for a lack of home preparation. “Teachers cause learning; schools determine winners and losers.”

Seabrook admits he can’t prove it, but he believes that “people operate under the assumption that when white kids walk into the schoolhouse door, they’re ready to learn. When blacks walk in, they must first demonstrate they are ready to learn. They assume there is a deficit, and as they try to take care of that deficit, the kids fall further and further behind. We end up with a remedially-driven curriculum. We not only track kids, we track teachers, track curriculum. It’s almost endemic to the educational system.”

And to his chagrin, Seabrook has found, the offenders aren’t just white, middle-class educators. Too many black teachers and parents also embrace this “culture of failure.”

Seabrook, who was a principal or superintendent in the Roxbury section of Boston, in Harlem and in East Palo Alto, California, before returning to his native Charleston in the 1980s, told writer Nat Hentoff years ago that an effect of racism is that “there are a lot of [minority] parents who do not believe their kids can learn. [Others] feel their kid is the lucky exception. I felt that way about myself. I was damn near an adult before I realized that all white people weren’t extra-smart, super-smart, in comparison to us.”

Lorin W. Anderson, a professor of education at the University of South Carolina who has studied the effects of desegregation in rural sections of the state, said the poorest schools not only get the worst teachers, but their para-professionals are likely to have only marginal training and skills. “If you put those aides in a class for gifted pupils, the parents would crucify them,” he said. But in a poor district they are used extensively because “they are cheap labor. And the outcome is fairly predictable.”

“No, it’s not the blind leading the blind,” Anderson said. “That implies they’re both moving in the same direction. This is the deaf leading the blind. There’s a lot of aimlessness; there is no purpose.”

Another effect of racism that State Superintendent Nielsen encountered when presiding over a community meeting in Summerton, is that “people are afraid to speak out.” The meeting attracted a large crowd, evidence that “they care about the schools,” Nielsen said, “but when you rent your house by the week, as many tenant farmers do, you learn you don’t always speak up.”

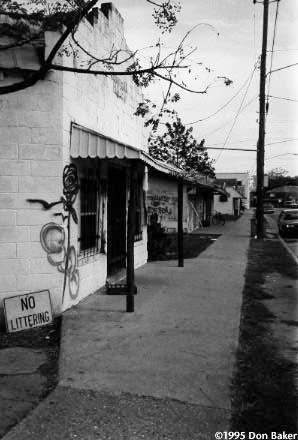

Community activist Alice Doctor-Wearing concurs. “No one attends council or school board meetings,” said Doctor-Wearing, who was one of only two residents who showed up for a special council meeting called to discuss the fate of the former whites-only Summerton High School. Doctor-Wearing is president of Scott’s Branch 76 Foundation (named for the year she graduated), which wants to convert the building, which stands vacant in the heart of town, into a civil rights museum and community center.

Lack of community involvement has allowed whites to continue to control events in Summerton. Even though at least 55 percent of its 950 residents are black, all seven council members are white, and only one black ever has been elected to the council. Blacks have fared better competing for the school board, whose members are selected from a wider area, and now occupy all but one of the seven seats.

Although there is little integration here, in the schools or elsewhere – whites eat at the Summerton Diner and live on the east side of town, blacks patronize the Sunshine Cafe and live on the west side – there are signs of inter-racial cooperation.

Some whites voted for the bond issue, approved by more than a three-to-one margin at a special election in 1992, that authorized appropriating $11 million for construction of the new high school and renovations of the district’s two elementary buildings.

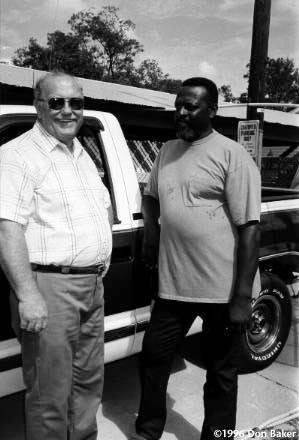

Summerton Mayor Charles A. Ridgeway, the stereotypical picture of a small-town Southern politician – heavyset, in jeans, plaid shirt and gold chain, leaning against the door of his pickup truck that has a gun in the cab – asserted that he “went out on a limb” in support of the bond issue because “the children deserved it, even though it increased our taxes by about one-third.”

Ridgeway, a sweet-talking fellow who owns a chain-link fence company and raises bulldogs, peacocks and chickens in his enclosed yard, observed that “most of your white people [with children] have moved out. And there’s no white children in the families that have moved in. You drive around town and see nothing but houses with old ladies, widows.”

The new Scott’s Branch High replaced a decrepit structure whose shortcomings inspired a young Thurgood Marshall in the early 50s to argue for the end of segregation before the U. S. Supreme Court. When the building finally was closed, in 1994, its hallways still were too narrow for lockers, requiring students to lug their books and other possessions from class to class, and its football field required all extra points to be kicked at one end, lest the ball wind up in an adjoining cemetery.

Blacks always have constituted a majority in cotton-growing Clarendon County, which is located midway between the state’s two metropolises, Columbia and Charleston, but so many white families with school-age children have moved away since segregation was outlawed that even if all the remaining ones sent their children to Scott’s Branch, there would be little integration. By one estimate, there are no more than 35 to 50 white children remaining in the district.

All but a handful of the remaining white families with school-age children either pay tuition to a local Christian academy, opened in 1965 as an alternative to integration, or skirt attendance laws and send their children to adjoining districts that have smaller black majorities.

“Why is it surprising that people who do not want integration will find a way to avoid it?” asks Professor Anderson. “The real story is why people expected it not to be that way. People will always find a way. All the national people [courts and Congress] do is push segregation to a different level.”

If segregation hasn’t continued at the district level, Anderson found, it surfaces in individual schools, and finally, if not there, at the classroom level.

Anderson maintains that South Carolina is not unique in that regard. “If you take these assumptions to Chicago, you’ll probably find the same thing.”

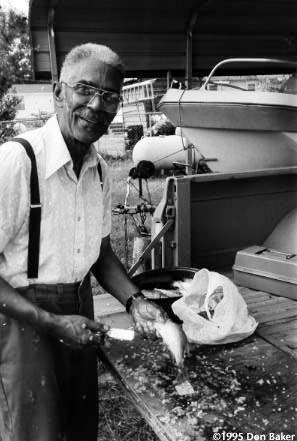

School board member Joseph R. Richburg, a petitioner in the early 50s law suit that led to school desegregation, said that “for a long time it looked like we won the battle and lost the war.” Because of his activism, his wife lost her teaching position and he was fired by the state veterans administration. To survive, they moved to Baltimore for a decade.

Now back at home, the 75-year-old barber is hopeful the new school, along with its new principal and superintendent, will spur morale and result in better education for the children.

As far as integration, “we don’t need the white people to have a good school,” Richburg said.

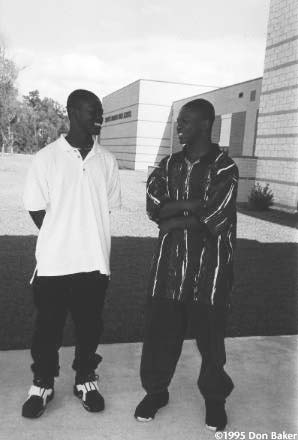

Even without the new facility, some students manage to overcome the odds at Scott’s Branch. Sixteen-year-old juniors Keith and Kenneth Nesbitt, who are twins, scored 1,080 and 980, respectively, on the SATs at the end of their sophomore year. By the time they are ready to apply to colleges – Kenneth is aiming for Yale, Princeton or Morehouse; Keith, who is more interested in athletics, for Clemson, Auburn or Georgia – both expect to be competitive.

Both are trying to make the most of the limited curriculum at Scott’s Branch – advanced placement courses in English and calculus, two years of French – but they have found it difficult to attract the notice of the kinds of colleges they are interested in. Neither Clemson nor South Carolina, the state’s major colleges, bother to send representatives on career day.

So who does recruit at Scott’s Branch? “The army,” deadpanned Keith. Last year, about one quarter of the school’s graduates joined the military.

©1996 Donald P. Baker

Donald Baker, on leave from The Washington Post, is examining the experience of schools since Brown v. Board of Education.