Six-year-old Shirley Ann Davidson had looked forward to starting school for a long time. Her mother had prepared her well, giving her the basics of arithmetic and reading from a Dick-and-Jane book to teach her the alphabet. During the summer before Shirley was scheduled to start first grade in Prince Edward County, Virginia, her mother made her a couple of new dresses and drove her into town for a vaccination and checkup. The year was 1959.

But on the day school was to begin, Shirley’s mother cryptically announced that “it wasn’t time yet” for her little girl to begin classes. The terse news was made even more puzzling when Shirley, the only black and only girl of school age in her neighborhood, watched her sometime playmates, Tommy and Billy, who were white, gallop down the driveways of their houses to board a school bus.

The right time for Shirley to begin school, it turned out, would not come for four years, as she became a pawn in the longest public school closing in American history.

Rather than obey court orders to integrate their schools, the white segregationists who ran Prince Edward County, encouraged by co-conspirators at the state capitol in Richmond, shut down both the white and black, separate-and-unequal, school systems in the county. Then, taking advantage of emergency laws enacted by the Virginia legislature, the county’s 1,450 white children enrolled in a private, segregated, tax-supported school, which was equipped with teachers, books, supplies and school buses from the former public schools. Shirley and the county’s 1,800 other black children were locked out.

Each morning that fall, and off-and-on over the next four years, Shirley watched with envy as Tommy and Billy walked to the edge of the highway to await the school bus. Shirley got to know the schedule by heart: At quarter to eight in the morning, the bus stopped on the highway across from Tommy’s driveway to pick up the boys; and at quarter past three in the afternoon, it glided past Shirley’s house and halted seventy-five feet to the west, and dropped them in front of the Hubbard’s rural mailbox.

After a while, Shirley began to pretend that she too was going to school. Following breakfast, she grabbed a couple books and, carrying them on her hip the way Tommy and Billy did – she had never seen the way girls cuddle books to their chest – headed to the highway.

“I remember sitting in the shaded part of those trees, waiting for the bus that wouldn’t pick me up. And for the bus that wouldn’t let me off. The bus that wouldn’t pick me up,” Shirley repeated, as though she still hasn’t accepted the reality of it. “That’s when I started playing school. I’d go out the door, skipping along, down the driveway, and then I’d sit on a patch of grass – there was a hedgerow all along the fence – and wait.”

She transported herself into a world of daydreams, filled with scenes in which the yellow bus stopped at her mailbox too. And for hours on end she read and re-read the few books that comprised the family’s meager collection. She forced herself to return to the house for lunch, and to help with the chores, which included pumping water from the well just off the back porch. Her mother required a lot of water because she took in washing and ironing to supplement the money her father brought home. He worked at a lumber mill that was a reliable, if scanty, source of income for many of the town’s black men.

On days that Shirley dallied too long down by the road, her mother asked, “‘where you been?’ and I’d say, ‘oh, been playing school.'”

Once Shirley waved to the children as the bus passed. The response was a motion she wasn’t familiar with – a middle finger thrust upward in her direction. “At that time I didn’t know what that meant, but I knew it wasn’t good, so I didn’t wave anymore,” she said. “My feelings were always easy to hurt. I guess that’s why it bothered me so much that the bus didn’t pick me up.”

The Davidsons and many other blacks in the rural, tobacco-producing county 70 miles west of Richmond misjudged the determination of their white neighbors to perpetuate segregation. Surely, the thinking went, after a while – maybe next week, or next month, or eventually, next year – they would come to their senses and concede that, like the Confederacy that surrendered just twenty-five miles west at Appomattox, segregation was a lost cause.

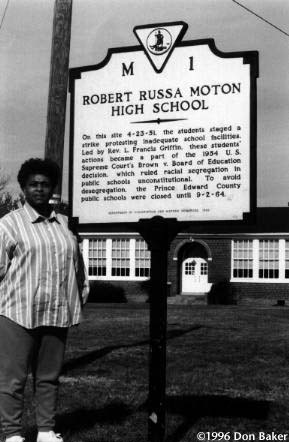

But the white citizens of Prince Edward County had been preparing for a showdown on school integration for nearly a decade, ever since April 23, 1951, when the 450 students at the R. R. Moton High School for Negroes – including Shirley’s mother, Hazel, then a ninth-grader – staged a strike to protest inadequate facilities there. Moton had been designed for 175 pupils, so to accommodate the overflow, the county put up three wood-and-tarpaper outbuildings in the back yard. Hazel Davis, Shirley’s mother, remembers that the temporary structures: “Everyone called them chicken coops. They were cold in winter and hot in the spring and fall.”

The strike ended after two weeks, but by then, the grievance had expanded from equal facilities to integration, and the NAACP filed a law suit in federal court attacking the Virginia law requiring segregated schools. A three-judge panel refused to end segregation, but found that the Negro schools in Prince Edward County were inferior to their white counterparts, and ordered that the facilities be equalized.

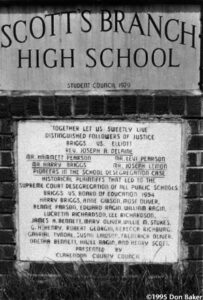

The NAACP appealed to the United States Supreme Court, where the suit was consolidated with similar ones initiated in Topeka, Kansas; Clarendon County, South Carolina, and Wilmington, Delaware. On May 17, 1954, the nine white male justices of the nation’s highest court ruled, in Brown vs. Board of Education, that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

The Virginia General Assembly reacted to the Brown decision by enacting a plan of “massive resistance” to integration that allowed the governor to block funding to any school district that attempted to desegregate, or came under a court order to desegregate. The General Assembly also provided tuition grants to whites who chose to enroll their children in private schools.

Whites in Prince Edward County moved quickly too, forming a foundation to operate a private, segregated school for the day that integration was ordered. That came on January, 19, 1959 – the birthday of Robert E. Lee – when state and federal courts independently ordered the county to comply with the law of the land.

By then, the foundation had secured pledges of $300,000 to operate a segregated school, named Prince Edward Academy, and had lined up temporary sites and teachers. (All but one of the white teachers agreed to move to the academy). When the academy opened in the fall, in a harbinger of school choice run amok, the white parents got the tuition grants from the state, and their children got their own subsidies from the county, financed by taxes assessed against all home owners, including Shirley’s parents.

There was never a formal protest of that taxation-without-representation, but years later, one of Shirley’s brothers-in-law, just back from fighting for his country in Vietnam, went to the courthouse and demanded a rebate on behalf of his family. It was summarily rejected.

Hazel and Robert Davidson never discussed the school closing with their children, and after an initial question or two, Shirley and her three younger brothers didn’t press the matter. “I just didn’t think the time had come for me to start to school,”‘ she said. She remembered some talk among her parents and grandparents about wishing the family could move to an adjoining county, where the schools remained open, and segregated, but nothing came of it.

Initially, after the schools failed to open, a few classes for black children were held in church basements and homes. They were taught by some of the displaced black teachers, along with volunteers from liberal organizations such as the American Friends Service Committee (Quakers), the NAACP, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and students from several Northern colleges. But those efforts dissipated after a year or two because of a lack of money, personnel and supplies. While a lucky few hundred students left the county to continue their schooling, the majority of the black students became part of a lost generation whose formal schooling ended abruptly, or never began.

It took a long time for the tragedy in Prince Edward to seep into the nation’s consciousness. Finally, in 1963, the Kennedy administration became involved.

“Something has got to be done about Prince Edward County,” declared President John F. Kennedy. He observed that “there are only four places in the world where children are denied the right to attend school: North Vietnam, Cambodia, North Korea and Prince Edward County.” The president dispatched his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, to Farmville, the seat of Prince Edward County, for a rally in behalf of public education that kicked off a $1 million drive for contributions from around the country. One of the hands that Robert Kennedy shook that day was that of Shirley’s mom.

As a result of the national spotlight, a privately-funded Prince Edward Free School opened on Sept. 7, 1963 for all students, although only a handful of whites attended. By that time, Shirley’s brothers also were of school-age, so all four of them started together. An integrated staff taught groups of children in an ungraded setting, allowing bright children such as Shirley to catch up quickly. The following year county officials bowed to new court orders and reopened the public schools to all races, although virtually no whites enrolled.

[Over the years enough whites have trickled back to the public schools to make up 40 percent of current enrollment in the county. The academy, nominally integrated, continues to exist, if not thrive. The old Moton school was used for the county’s fifth graders until this summer, when an expansion at the middle school was completed, prompting the school board to declare it surplus property. The board gave the building to the seven-member board of supervisors (three of whom are black), which is weighing alternatives, including selling the property to the highest bidder. Some black leaders in the community hope to convert the building into a museum, to commemorate its role in the civil rights movement.]

In the reopened public schools, Shirley was placed in the fifth grade, one year behind. After that she stayed on schedule, graduating in 1972, one year later than she would have had the schools not closed.

Until recently, Shirley, like the victims of childhood abuse that she and the other black pupils surely were, had repressed her recollections of how she dealt with the school closing. “I was embarrassed to tell it,” she said.

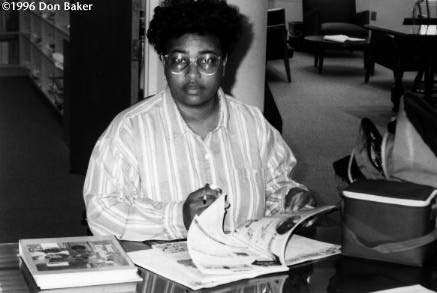

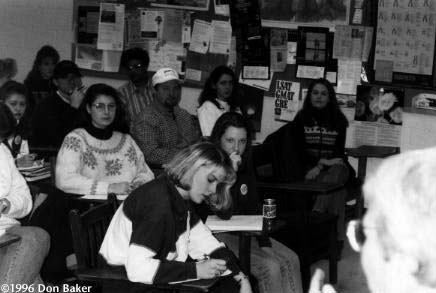

But this spring, as part of an honors class at Longwood College in Farmville, where she is working toward a degree in elementary education, 42-year-old Shirley Davidson (Eanes) let the memories flood her mind, and moisten her eyes, during an oral report of her experiences that left her classmates, most of whom were young and white, gasping in disbelief.

Her professor, Susan Bagby, predicted, “Shirley’s going to make a very, very good teacher.”

©1996 Donald P. Baker

Donald P. Baker, on leave from the Washington Post, is studying the legacy of Brown vs. Board of Education on the communities where the law suit began.