Quillabamba, Peru – The decrepit old theater, filled with hand-lettered signs and women in bowler hats passing out coca leaves, seemed worlds away from the high living associated with the illegal drug trade. So did the calls for all-out war on “el narcotráfico.” But its designation of coca as a traditional natural resource of the Andes, like its condemnation of U.S. efforts to eradicate the coca crop, turned the annual congress of the Andean Coca Council into an overt challenge to U.S. drug policy.

“They can’t have it both ways,” a U.S. development official said recently. “They’re either in coca or they’re not.” It was the kind of pat dichotomy that has produced what Peruvians call “a dialogue of the deaf” between coca farmers and counternarcotics officials. For unlike the foreign technocrats sent to fight the drug war, who see coca as merely the raw material for cocaine, Andean farmers view their coca through a nuanced lens of culture and history, as well as economics. Though many want out of the illegal drug trade, coca itself makes a lot of sense as a tropical crop. So when the U.S. offers of eradication and “alternative development,” an increasing number of farmers organized in the multinational Andean Coca Council ask for “integrated development with coca,” for which they seek legal uses.

Sadly, because coca has been, in the words of Peruvian historian María Rostworowski, “demonized since the Spanish Conquest,” a debate between the two approaches has never taken place. So the question remains open: might expanding coca’s legal uses make more sense than eradicating it?

Carlos Barrantes, a farmer from Peru’s Apurímac Valley and recently elected leader of the Andean Coca Council, thinks it could. Barrantes was a leader of the peasant defense squads that fought the Shining Path insurgency to a standstill in the Valley, and he wants no quarrel with the government. He knows the Valley’s coca production outstrips legal consumption, but like many coca farmers he is convinced that if coca got a fair hearing internationally, legal demand for it would increase. He added that wherever eradication has been tried in Peru, “it only dispersed the coca.”

Barrantes recently took a motorized canoe up the swift-flowing Apurímac River to Palmapampa, a former narcotráficante haven, to tell fellow farmers about the Andean Coca Council’s effort to clean up coca’s reputation. He had some harsh words for them. “This may shock some of us,” he said, “but we should declare war on the drug trade.” He told them to let some of their coca fields go unharvested, and urged them to relearn traditional techniques of preparing the leaf for chewing and tea. “We’ve gotten accustomed to preparing our coca for the drug traffickers,” who take leaf any way they can get it, he said. “Now we have to produce better quality.”

To many Peruvians the Council’s efforts seem Quixotic. “We’re stuck with what the U.S. wants,” sighed Rosa Urrunaga, an ethnobotanist at Cusco’s San Andres University. Walking up one of Cusco’s steep avenues after an afternoon class, she outlined coca’s benefits. With help from traditional healers in Quillabamba, the heart of Peru’s legal coca production, she has identified 52 pharmocological properties of the coca leaf. Although international condemnation of coca has discouraged research, studies outside Peru have confirmed many of her findings.

A short mestiza woman, Urrunaga grew up in Quillabamba, surrounded by the traditions and rituals of coca. Today she is a bitter opponent of the condemnation coca receives internationally, a campaigner who has experimented with making coca toothpaste, chewing gum and anti-inflammatory creams, and a fierce critic of her own country’s ambivalence towards it. “We have to be more aggressive,” she said. “Coca is part of our history. We have to speak out. We know what’s going on against coca, but we do nothing.”

Urrunaga blames U.S. pressure, but coca has been arousing baffled scorn in outsiders for more than four hundred years. The Spanish chronicler Pedro de Cieza de Leon, who sailed to South America in the wake of Francisco Pizarro’s conquest of the Incas, wrote in 1553: “All through Peru it was and is the custom to have this coca in the mouth When I asked some of the Indians why they always had their mouths full of this plantthey said that with it, they do not feel hunger, and it gives them great vigor and strengthIt seems to me a disgusting habit, and what might be expected of people like these Indians.”

The vigor and strength the Indians received from coca, which they mixed with a little ash or lime and sucked in a wad in their cheeks, ushered in what might be called the first coca boom after the 1545 discovery of the silver mines of Potosi. A mild stimulant and anaesthetic which suppresses hunger pangs, helps the body process carbohydrates and regulates glucose levels, coca contains vitamins A and B1, calcium, iron and phosphorous. It became indispensable to the overworked, underfed Indian mineworkers. Luis Capoche, a Potosi mine owner of the time wrote, “There will only be a Potosi while there is coca,” and coca production increased fiftyfold.

But there was a backlash. The coca fields were exploited at a high cost in Indian lives, as workers sent from the cold, dry highlands suffered in the hot, humid coca fields. The Church, which opposed coca on humanitarian grounds and because it played a key role in native religion, led efforts to ban it. According to a 16th century friar, Francisco de Morales, “The Marquis of Cañete, who was viceroy of Peru, tried to uproot it and had much of it uprooted and if he had lived and governed he would have uprooted it all and given orders that this plant be substituted by another, better, kind of farming.” Cañete’s effort goes down in history as the first eradication and alternative development plan in the Andes, and perhaps in the world, but it failed. By the late 16th century, coca was an accepted part of colonial life, though changing customs and the declining Indian population ended its first boom.

In 1860, a German chemist isolated the cocaine alkaloid, launching a second coca boom and a period of almost universal enthusiasm over cocaine. Sigmund Freud wrote a treatise on it, and in a letter to his fiancee said, “A small dose lifted me to the heights in a wonderful fashion.” Sherlock Holmes injected cocaine, telling Dr. Watson that it was “transcendently stimulating and clarifying to the mind.” Coca-Cola and a dozen other “tonics” featuring coca extracts promised consumers that it “made the sad glad and the weak strong.”

This 19th century boom led to a backlash which swept coca onto the same conceptual heap as cocaine. In 1914, the United States Congress passed the Harrison Act, the first of many laws aimed at fighting domestic drug abuse. The Hague Opium Convention of 1912 was, likewise, the first of several international treaties calling for controls on coca production. It was followed by additional agreements in 1925, 1931, 1936, 1946, and 1953, all of which were codified into the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotics Drugs, which was followed by the 1988 Vienna Convention.

Over those same decades, white Lima intellectuals began to blame the misery of the highland Indians not on poverty and isolation, but on coca. In 1938, one Lima doctor, Luis Saenz, worried that the number of “these eugenically defective and coca-retarded elements” was growing.

Driven by concerns like these, Peru sought and received a visit by a U.N. panel of experts who in 1950 deemed coca chewing harmful and recommended its eradication. Though those results have been bitterly contested ever since, the 1961 Convention ordered Bolivia and Peru to eliminate coca chewing by 1989. The 1988 Vienna Convention, which recognizes traditional use, nevertheless declares that the obligations imposed by the 1961 Convention remain in effect.

Today, a modern generation of experts like Baldomero Cáceres and Rosa Urrunaga demands a reevaluation of coca. A Peruvian social psychologist and avid coca chewer himself, Cáceres believes that research on coca would be more useful than all the economic and law enforcement aid targeted against coca. “There’s cocaine in coca,” he admitted. “There are also several other alkaloids, vitamins, and minerals. Coca should have a worldwide market and instead it’s in the defendant’s chair.”

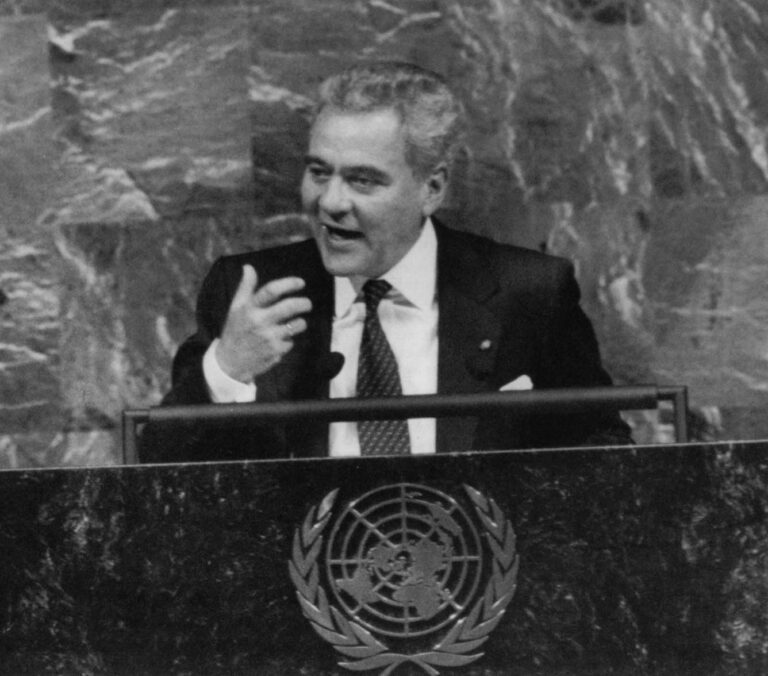

That may finally be changing. The Andean Coca Council has a network of supporters in Europe who are pushing their governments to legalize imports of the leaf. In 1994, the presidents of Peru, Alberto Fujimori, and Bolivia, Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada, agreed to work together to remove coca from the blacklist of the 1961 Convention. At the Quillabamba meeting of the Andean Coca Council, Peruvian Agriculture Minister Absalón Vásquez promised that the government would promote research into beneficial uses for the coca leaf.

But such efforts face stiff U.S. opposition, which continues to insist on eradication. Bolivia’s president, faced with U.S. threats to cut off assistance and to vote against loans to his aid-addicted nation, has backpedalled on coca and is pushing ahead with eradication campaigns.

Such a strategy baffles Baldomero Cáceres, given that Bolivia eradicated 63,670 acres of coca from 1986 to 1994, only to replant another 83,352 hectares over the same period. Cáceres offers a different vision. “Imagine a million more coca chewers in Peru,” he said. “That’s 10,000 tons less coca for cocaine.”

©1996 Corrine Schmidt

Corrine Schmidt is a freelancer in Lima, Peru examining the environmental effects of the cocaine market.