The United Gnegnos of America held their annual ball recently at the Bronx’s Parkside Plaza. Gnegnos (pronounced “NYE nyose”) are a caste, actually the lowest caste, among the city’s 20,000-odd Senegalese immigrants. To attend a Gnegnos function, to have even heard of it (I received an engraved invitation with the afternoon mail) is to note the critical mass of settlement that Senegal has brought to New York. And that is worth celebrating.

Amid vintage Outer Borough, folding-chairs decor, a DJ pumps an Original Homeboy beat from a plexiglass booth. Striking women arrive wearing peach and purple gowns with matching turbans. They file into the ballroom, their escorts in long cotton sheaths, called boubous, of Nile blue or oasis green. Over the din, conversation bubbles in tongues so exotic it sounds like laughing children rolling down a hillside. In sailor suits and pinafores Gnegno kids break ranks to attack a modest buffet: Ritz crackers on a bed of Cheez-Nips.

Africa has arrived in the South Bronx in a big way over the past five years. In an adjacent room, the local Gambian club is holding its monthly meeting. Outside, along the Grand Concourse, immigrants stroll by in their Sunday finery – Ghanaians in patterned wrap-around dresses, Nigerians in billowy pastel gowns. Malians in white roll-up trousers under ponchos of dusky “mud” cloth. The doorways of the old art deco apartment buildings grew shabby during three decades of decline. But now, block by block, the appearance of new life – here an African restaurant, there a hair-braiding boutique – show the turn-around has begun.

Inside the Parkside Plaza, the music is funky enough to humble the blaringest Santo Domingo-mobile cruising outside. Just like in junior high it lures the girls first, a whirl of bright boubous and cocktail dresses. The boys follow stiffly, led by partners or pushed by pals. A mirrored disco ball sprinkles flash on gold thread bracelets, pagers and cans of soda. Gnegnos are Muslims, so the bar is closed.

Only a step up from slaves, gnegnos are Senegal’s untouchables. “Gnegnos stayed home during wars to make weapons,” a man wearing a maroon boubou and a diamond in his left ear explains, shouting over the party noise. Here they’re a mutual aid society. “Some boys robbed my cab in Queens,” Abdoulaye Seck, the man in maroon, shouts. “Shot me all over my stomach and legs.” For six months caste-brothers paid Abdoulaye’s bills.

A gnegno is four things, explains the vice president of the organization, Mourtala Sall, also a cab driver. He is a weaver, a goldsmith, a woodcarver or a leather-worker. Gnegnos are the caste at the bottom of each of Senegal’s competing tribes, sort of an anti-tribe of trained artisans. Like other immigrants before them, gnegnos are well positioned to thrive in a new land.

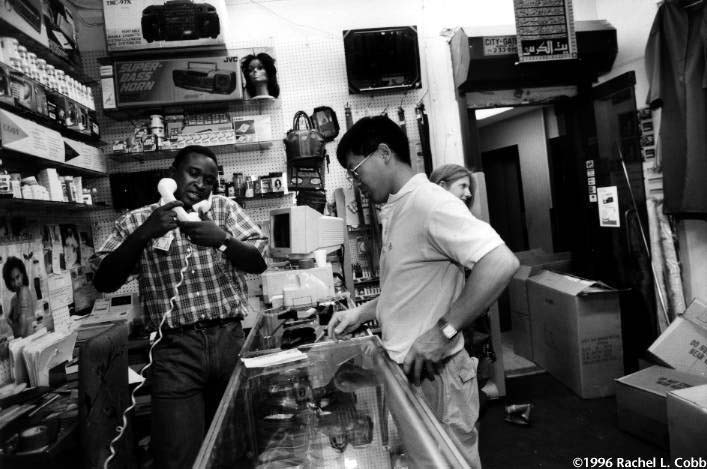

Why thrive? Because their skills qualify them for the unique business opportunities open to Africans in America servicing the culture-starved diaspora of middle class African-Americans longing for a Little Italy or Chinatown of their own. Senegalese make the dresses American blacks want to wear, fashion the jewelry and carve the statues they buy for their living rooms. In Harlem boutiques, at summer street festivals, or from the backs of vans parked anywhere at all, hundreds make a living this way, many of them gnegnos.

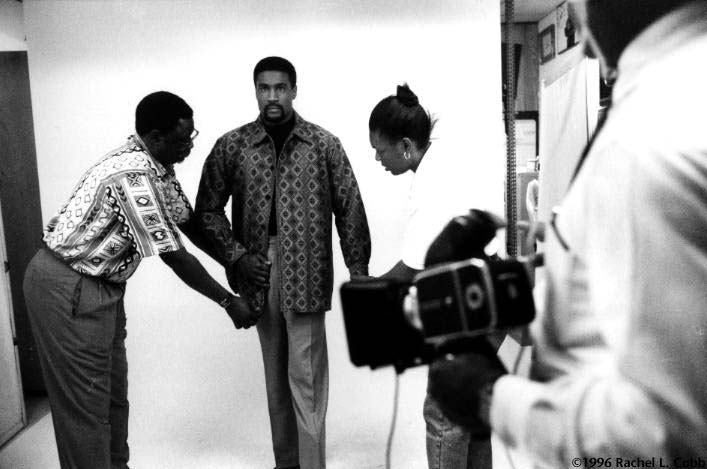

Their outcast status at home, moreover, makes gnegnos among the most likely to stay in America. Why be a doormat in Dakar, when you can boom in the Bronx? In New York, gnegnos are reinvented as cab drivers, dishwashers, college students or street vendors. Thanks to a sympathetic immigration judge or a new wife, some even have green cards. So on party nights they dress for reinvention, exposing the inner man being what he couldn’t be at home: in brocade for Tribal Leader, white for Koranic Scholar, a tailored suit for Monsieur Le President, baggy-jeans-and-beeper for Gangsta.

Mourtala Sall, thirty-seven, has been in New York for seven years. With a green card he is among the elite now. But for his first two years he worked stocking grocery shelves, moonlighting, quite literally, as a gypsy cab driver. Today most of the unmarked, off-the-books car services employ French-speaking Africans. It is dangerous work, restricted to streets in some of the country’s worst neighborhoods. In the past five years, 28 Senegalese cab drivers have been murdered in New York City alone. But it’s a way to raise cash quickly, and learn enough to work for the yellow cabs downtown, where risks are lower.

Mourtala’s green card was probably obtained fraudulently. He isn’t sure, insisting only that he qualified for the amnesty written into the 1986 Simpson-Rodino Immigration Reform and Control Act. That amnesty was available to anyone who could prove permanent residency since 1982. Mourtala says he first came in 1981, but travelled back and forth between continents before entering for the last time in the late 1980s. There are many ways to “prove” permanent residence, however, everything from having an old phone bill to registering for night school. There are also many Senegalese named “Mourtala” (the name of a leading Senegalese cleric) and “Sall,” and he easily could have used someone else’s documents. Then there was the separate amnesty for agricultural workers, which many Senegalese exploited.

All Mourtala knows for sure is that it cost $1500 for a lawyer and, after a long wait, he had a green card. That allowed him to send for his wife, and build a new life in America.

Like most Senegalese immigrants, Mourtala Sall is a Mouride, a disciple of a Muslim sect that dominates commerce in Senegal. The first Mourides came to America in the late 1960s, international traders whose contacts already spread across Africa and into Europe and the Far East. They came selling African items prized in the West – antique carvings, diamonds and gold – and left with cargo prized in Africa. “It doesn’t speak well of my people’s development,” says Mohammad Diop a long-time Senegalese businessman, embarrassed by the memory. “They came for things like hair-straightener, skin lightener and wigs.”

Europe, in the 1960s and 1970s, had no companies producing cosmetics for black consumers. Black Africa, then and now, had little industrial capacity of any kind. Thus, the obvious trade route linking Jeri Curl, Skin Bright and Taking Care of Business hair gel to customers in West and Central Africa ran directly through Dakar, Senegal – and the Mouride traders running the Sandaga market there. By the late 1970s a small colony of New York residents handled wholesale distribution for the Mourides back home, shipping containers home either by boat or Air Afrique to Dakar. In the 1980s, more Mouride disciples came, “democratizing” what had been a closed cartel by flooding the streets with peddlers trading handicrafts for dollars.

Several factors contributed to the community’s growth, but the most important was the rise of an African American middle class that knew Africa. The same traders who came to New York sold souvenirs to American tourists in Africa, most of them black. In time, they realized the profit in going to the customer directly. Another wave was launched – university students and professionals arriving with tourist visas, packing tourist trinkets to sell, and going home with “souvenirs” they sold at high mark-ups in Dakar: Janet Jackson t-shirts, stereo boom boxes, blue jeans and, always, cosmetics. During summer months, African street festivals in every U.S. city attract throngs of Senegalese peddlers, many earning thousands of dollars on a single weekend selling boubous, drums, wood carvings and jewelry.

By 1994, when Senegal’s Banque du L’Habitat du Senegal (the National Housing Bank) opened a remittance office in New York, an estimated $10 million in trade was crossing the Atlantic every year from Dakar to New York. Seydou Lo, BHS bank’s New York director, explained that before his bank came, residents sent money home through the traders. “A Mouride comes, visits everyone he knows in New York, and collects dollars to take back to their families,” he told me. “But they use the dollars to first buy things here – like electronics and cosmetics, then they sell them in Dakar and distribute francs to the family with the profits.”

Today BHS has competition, plenty of it. Other remittance services wire cash home; even Western Union has discovered the African trade. But the market is growing. From African souvenirs to African fashions to African food, Senegalese are discovering that America’s black population – at least five times greater than Senegal’s – has only begun to be tapped. Africans are striking out for the provinces, too. Wherever black Americans sponsor African Pride festivals, or Blues Weekends, or Down Home Family reunions, Senegalese peddlers go to peddle cheap souvenirs from the Mother Country. Many, even those who are illiterate, subscribe to national newsletters that print the schedule of the year’s events, then travel around the country like gypsy bands. The most ambitious found new businesses, thus you can find Touba Fashions in Atlanta, Touba Gold and Jewelry in Silver Spring, Md., Touba Liabden-Mouridin in New Orleans, and West Africa Touba Art in Miami.

America, compared to the closed world of Muslim Senegal, is also proving to be the promised land for Mouride women. Hair-braiding is a business exploding in ghettos across the country, a lucrative one that allows unschooled housewives to earn $50 to $100 for just a few hours’ work. At least thirty Senegalese entrepreneurs have established braiding salons in New York, others simply rent chairs at existing beauty parlors, paying a fee to the owner then bringing their own clients. Mourtala Sall’s wife braids hair in her kitchen off the Grand Concourse.

The ability to create two-income families means the Senegalese wave will continue to grow. Hardly a week goes by now without at least one new birth in the community. Last year, New York’s Board of Education circulated notices, in French, for Harlem parents with children in public schools. By the time Mourtala Sall’s two-year-old starts school, she can expect plenty of African classmates.

©1996 Joel Millman

Joel Millman, an associate editor of Forbes magazine, is researching African and Caribbean immigration.