Family values, religion and community renewal are among the pillars of conservative ideology, and rallying-points of Republican legislators who tend to represent districts that are rural, white and affluent. In Democratic Brooklyn, particularly the mainly black, mainly poor neighborhood called Fort Greene, the Republican Personal Responsibility Act is mere Beltway Speak for policy that has been evolving for decades.

The PRA, which would evict legal immigrants from welfare rolls and other federally-funded anti-poverty programs, will have little impact on the parents of children at the Hanson Place School. Hanson Place celebrates its thirtieth anniversary this year. Since 1965 it has moved from the basement of a former Jewish synagogue to a six-story building at the corner of Lafayette Avenue and St. Felix Street, in what used to be a casket factory. A lot has changed in thirty years, and a lot hasn’t. Gloria Nelson, who taught second grade here in 1965, now greets children whose parents were her pupils. Another teacher, Mrs. Barker, taught Principal Alan Chase when both were living in Trinidad. “He was kind of quiet and shy back then,” she says with a sly smile. “Not as aggressive as now.”

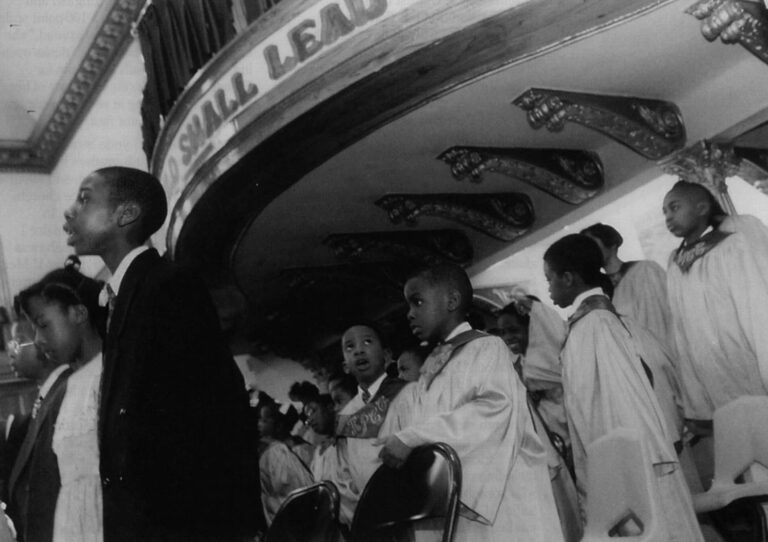

Chase, a bear of man with his own engaging smile, channels aggressions into preparing children to resist a world of sin. All but three of his 292 students are black; all come from families most Americans would consider poor. Chase’s school belongs to the Hanson Place Seventh Day Adventist church, a denomination that has flourished in black Brooklyn with a tide of Caribbean immigration. Strict vegetarians, SDA’s are the “health nuts” among fundamentalist Christians. Tobacco and alcohol are forbidden and their schools are known in Brooklyn as havens of discipline, Bible study and strong community involvement.

There are 40,000 members in the SDA’s Northeast Conference, virtually all Caribbean immigrants. The congregations have built a network of fifteen schools, opening six in Brooklyn alone. Esmee Bovell, an immigrant from Guyana, administers an education budget of $6 million, almost all of that paid by tuition. “The conference would not have survived,” she affirms when asked about the impact of Caribbean migration. “They might have had one school, but not fifteen.”

Every school has a waiting list. Although most students are church members, there is increasing enrollment from African-American households, including children of parents on welfare, who scrimp to save the annual $2000 tuition. Caribbean immigrants have swelled enrollment in Brooklyn’s Catholic, Episcopal and Lutheran schools, too.

Classes at Hanson Place School, where Bovell was principal until 1992, run from pre-kindergarten through eighth grade. Teachers’ salaries max out at $32,000, roughly half what a senior public school teacher earns. There is no basketball gym. Walkman radios, earrings and Nintendo games are forbidden. Lunch is served in a chilly loft with a view of the Brooklyn waterfront. There is a chapel, however, and regular Bible study. The school also boasts a new, $10,000 science lab, built by parishioners.

Across the borough is Crown Heights’ Hebron SDA Bilingual school. Most of Hebron’s 400 children come from Haitian homes, but “bilingual” does not mean a Creole-to-English transitional program. At Hebron children complete a rigorous curriculum conducted simultaneously in English and French. Sandra Fortin’s kindergarten begins homework the second day. Test papers–the alphabet and learning to count in English and French–are graded on a 100-point scale. “If I stop the work they fool around,” she explains over the clatter of 29 desks opening to exchange math textbooks for French readers. Fortin says most of her students are reading at second-grade level by the time they enter first.

About a third of Lynda Straker’s Hanson Place eighth graders have been here since pre-kindergarten, and about a third worship at Hanson Place church. Only half live with two parents. In answering a two-page questionnaire I prepared, they revealed themselves as typical Brooklyn teenagers: Boyz II Men and Salt ‘n Pepa are their favorite entertainers; John Starks and Patrick Ewing (an immigrant from Jamaica) are their favorite athletes. John 3:16 is their favorite verse of Scripture.

Ruben James, 14, lives with his mother and four siblings, while a fifth attends Alabama’s Oakwood College. Ruben hopes to enter Northeast Academy, the SDA’s Manhattan prep school, where an older sister is in 11th grade. That’s if his mother can raise the tuition. On the questionnaire he described her as “working for the Board of Education.” Elizabeth James, who immigrated from St. Lucia in 1975, works part-time as a server in public school cafeterias. Her take-home pay barely exceeds the $900 a month she pays in religious school tuition, but she is committed to a private school education. “I consider the children my bank account,” she says. “They are clothed and fed. Anything left goes for their education.”

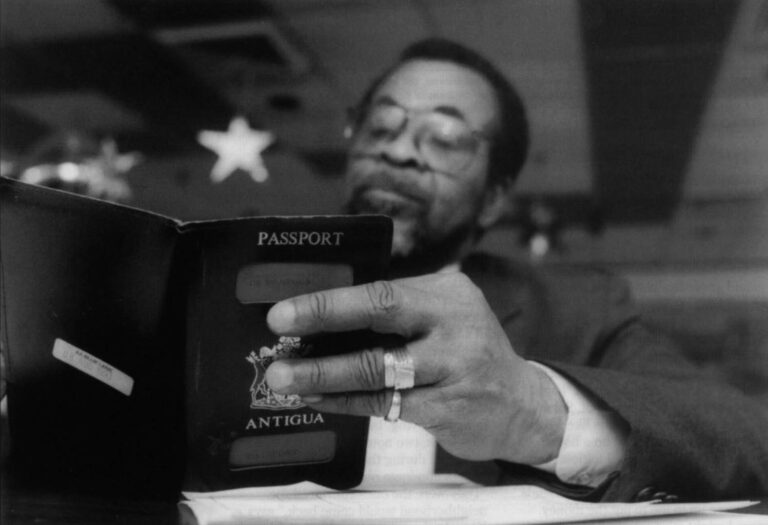

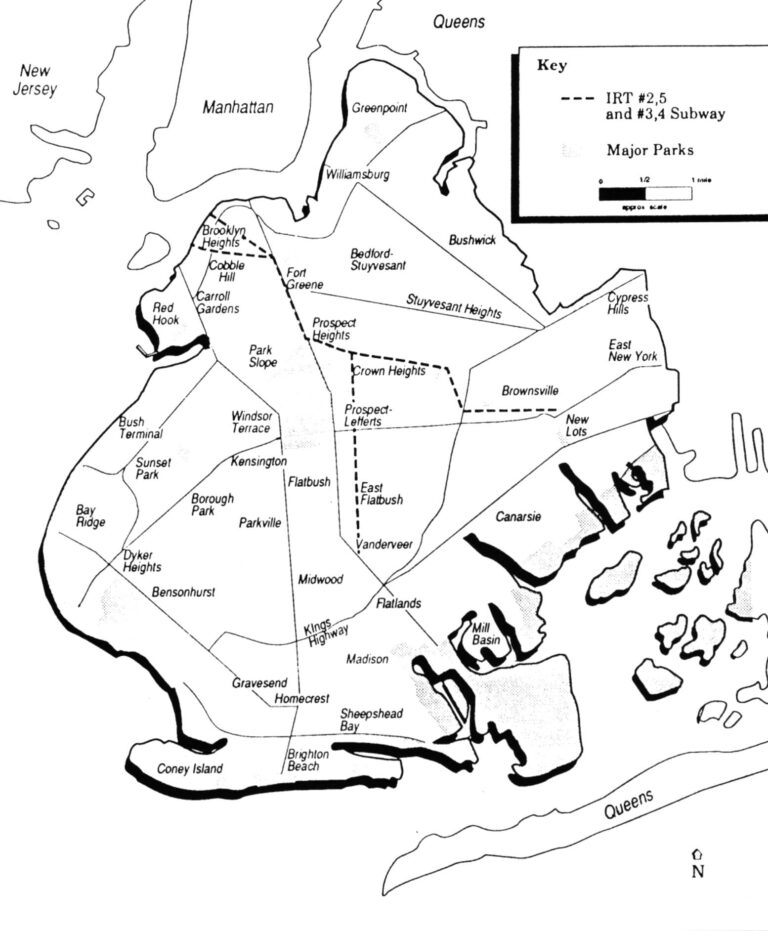

Of 700,000 legal immigrants who came to New York between 1982 and 1989, five Caribbean countries–Jamaica, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, Haiti, and Barbados–sent nearly a third. Thousands more came from smaller islands, or from Central America, whose black immigrants are counted as “Hispanic” in the Census, but who have historic ties to the English Caribbean. Today Caribbean immigrants and their descendants outnumber U.S.-born blacks in Brooklyn and Queens, and are fast becoming a majority of blacks city-wide.

Caribbean progress in black Brooklyn runs counter to popular beliefs about antagonism between blacks and immigrants in the inner city, or that immigrants are a drain on cities. In fact, blacks living in cities that attract immigrants–such as New York, Miami and Los Angeles–suffer less unemployment and have higher incomes than do blacks in cities like Cleveland, St. Louis or Detroit. This is partly because immigrant enterprise tends to raise all economic boats. And because, especially in New York and Miami, so many blacks are also immigrants.

For New York, Caribbean immigration has been a powerful, unplanned anti-poverty program–albeit one that is linked to many that came before. One reason Caribbean immigrants come here is the availability of public sector jobs. Poverty, a recession-proof industry, means hundreds of jobs for low-skilled newcomers. Often located in high-crime areas, jobs that are unattractive to native-born Americans are tailor-made for immigrants.

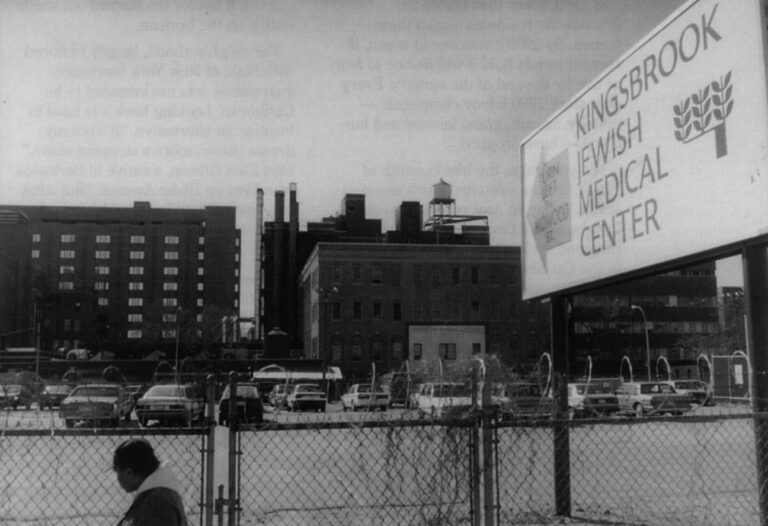

Take health care: throughout the five boroughs hospitals alone generate over $10 billion in annual salaries, much of that paid by Medicaid and Medicare. In parts of Brooklyn, public and private hospitals provide over half the paychecks, serving as life-support systems for entire neighborhoods. In some institutions, most jobs are held by immigrants while most patients are impoverished African-Americans.

“There is a fundamental demographic fact: southern blacks are not coming to New York in the numbers they used to,” explains Dr. Waldaba Stewart, a Caribbean immigrant, board member of Kings County Hospital and former New York State Senator. “The typical immigrant is willing to take any job; many times, jobs that other Americans are not willing to take. In hospitals, they end up taking janitor jobs, disposing medical waste, or lifting a 200 pound patient. These are hard jobs.”

For Caribbean immigrants who arrived after 1980, health care replaced manufacturing as the stepping-stone to the middle class, just as the hospital, with its round-the-clock work force, has replaced the factory. Woodhall Avenue, running through the heart of Caribbean Flatbush, is a 1990s version of Henry Ford’s River Rouge, the farmland-turned-motor works south of Detroit. Four separate health complexes are squeezed into eighteen blocks between New York and Utica Avenues: Kings County, SUNY Downstate; Kingsbrook Jewish, Kingsborough Psychiatric Center. Combined, they provide nearly 14,000 jobs, with a payroll exceeding $300 million a year. Those paychecks, and a Caribbean propensity towards home ownership, are transforming the ghetto.

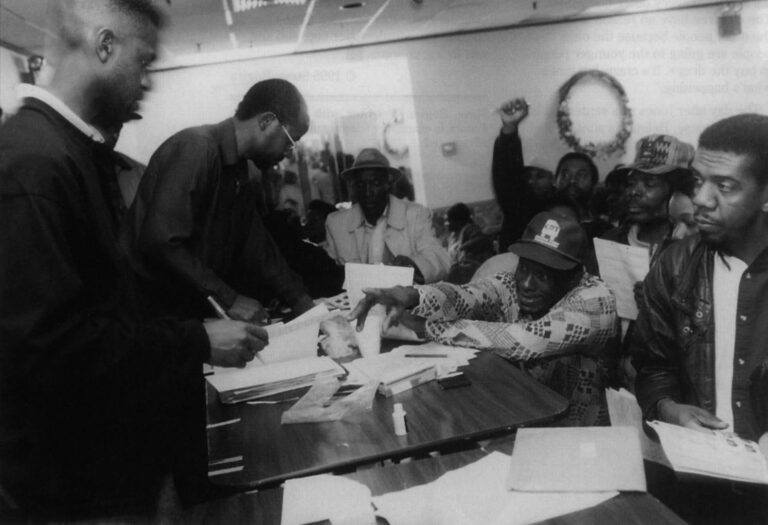

Gloria Nelson, Hanson Place’s veteran second grade teacher, is also the school’s “su-su” banker. Su-su is an old African term, transplanted to the Caribbean, meaning “cooperation.” Su-su circles are informal savings clubs whose members contribute an agreed-on amount each week (or each month), taking a “hand” until every member wins a pot. Some use the money for special events like a trip home or a down-payment on a house or car. Some use it for school tuition. Some simply hold it–to make sure they meet coming su-su obligations to their friends. “If it were up to me to put the money away, I might miss a week,” Mrs. Nelson says. “This way I never miss.”

Su-su is savings enforced by peer pressure. Like the religious schools, it is another weapon in the Caribbean anti-poverty campaign. Home ownership is on the rise because Caribbeans are fanatic savers, and because banks are recognizing su-su as a legitimate source of cash. Chase Manhattan, which has written over 200 mortgages based partly on su-su down-payments, mentions su-su in advertisements targeted at Caribbean neighborhoods. So does Republic Bank.

Not every mortgage is a result of su-su, but there is no question that rising Caribbean incomes are behind the surge in home-buying. In Brownsville and East New York, two notorious ghettos that imploded during the 1970s, Caribbean buyers dominate reclaimed blocks. “They were the ones convinced the neighborhood would come back,” says Ken Thorbourne, a housing activist, and son of Caribbean parents. “And they, more than a lot of folks, are able to come up with the down-payment.”

In 1980, fewer than one in ten Brownsville residents owned their homes. By 1990 it was one in seven. If current trends hold it will be one of four or five by the end of the century. Every year since 1990 felony complaints–murder, assault, grand larceny and burglary–have dropped.

Ten years ago, the blocks south of Pitkin Avenue stretched like a moonscape. Today, in neat rows of two-story homes, over a thousand families have returned. At least half either were born in the Caribbean, or have one parent who was. Festooned with satellite dishes, many with motorboats parked on trailers, homes along Herzl, Strauss and Amboy Streets could be mistaken for suburban condos, if not for the burned-out shells visible on the horizon.

The neighborhood, largely restored with State of New York mortgage guarantees, was not intended to be Caribbean. Looking back it is hard to imagine an alternative. “It’s not my dream house, more a stepping stone,” says Elon Gibson, a native of Barbados who lives on Blake Avenue. “But what can I say? Crime is down. It’s been a great investment.”

@1995 Joel Millman

Joel Millman is an associate editor of Forbes magazine who is researching African and Caribbean immigration.