Note: Many of the Pictures used in the original APF Reporter issue are copyrighted and could not be used in the web eddition

Daniella Henry remembers her first visit to Delray Beach. Driving up from Miami one night in 1990, she exited brightly-lit Interstate 95 for Atlantic Avenue, the town’s main drag. She was delighted to see streets filled with people in a festive mood, despite the late hour. “I thought it was a carnival,” she says, her natural smile brightening. Delight quickly turned to horror: “No carnival. Drugs.”

Delray Beach in 1990 was a notorious crack zone. Tourists bypassed the Palm Beach County town on their way to Fort Lauderdale and Miami, but locals would dart in out to score drugs. Most other downtown businesses fled, leaving a tax base dependent on winter snow-birds from Michigan or New York, and widows living in bungalows or retirement homes. A redneck power structure enforced a tradition of segregation, a breeding ground for civic corruption. “The police chief collected rent on Friday nights,” recalls Virginia Snyder, a local muckraker and private investigator. “Black tenants fall behind? He made the rounds for landlords.”

Today, Delray Beach is a model of civic restoration. Last year a cover feature in Florida Trend, a glossy business monthly, named Delray Beach “The Best Run Town in Florida.” Michael Bird, heir to the Woodruff Coca Cola fortune, just moved in. So did Office Depot, coming up from Boca Raton. Daniella Henry returned in 1992.

When she drives along Atlantic Avenue today she no longer sees a crack carnival. The strip has blossomed into Pineapple Grove, a pedestrian mall with art galleries and boutiques. A new tennis center brings Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova to courts erected in the heart of the old black ghetto. But the area still is black – a rare case of gentrification without displacement. From bitter segregation to racial harmony, Delray Beach has enjoyed a remarkable renaissance. And it occurred despite – or because of – someone new: Haitian immigrants.

The 1990 Census recorded just 10,492 Haitians living in Palm Beach County. At least 60,000 live there today, with some 15,000 concentrated in Delray Beach. The community is tiny compared with Miami’s Little Haiti, but as a percentage of the whole, Delray Beach is America’s most “Haitian” town – more than a quarter of its residents claiming some tie to Haiti.

The Haitians’ contribution to gentrification is seldom recognized (Florida Trend mentioned neither Haitians nor immigrants) yet undeniable. Fanatic workers and savers, Haitians swept through black Delray Beach like a conquering army, buying homes and transforming crime-corridors into stable, drug-free neighborhoods. Gripping Interstate-95 like a vise, the Haitian enclave choked off the drug trade by occupying a no-man’s land, eliminating potential crack houses with every new household.

County officials are thrilled, particularly with the Haitian families who have participated in the Restore Our Neighborhoods program to rehabilitate derelict housing. “We’re used to single-parent families,” says Chauncey Taylor, a local housing official. “It’s super when you see mom, dad and the entire family come in together for an application.”

Since 1990, more than 300 new homes have been built in a corridor once notorious for crime. Most house Haitians. Yet, even more important, Haitians broke a tradition of apartheid. Today the “black” blocks are integrated communities like Osceola Park, with a mix of Anglo, Latino and Caribbean families. It’s easy to find the Haitians. Their homes are well-kept, but have twice as many cars outside – the better to deploy the many wage-earners inside. “The Haitians broke the color line,” community activist Carolyn Zimmerman told me. “They didn’t know blacks lived on one side and whites on the other.”

As with most immigration, the Haitian wave was spurred by demand for labor – at first, farm labor in the fields between Lake Okeechobee and Interstate-95.

In the curious way race defines place in America, Haitians were conspicuous outsiders the moment crops were harvested, yet invisible after relocating along the coast. Delray Beach offered proximity to glitzy Boca Raton to the south and ritzy Palm Beach to the north. Renting homes from absentee landlords, and taking traditionally black service jobs, Haitians melted easily into the tropical ghetto, and discovered that being invisible is the first step to prosperity.

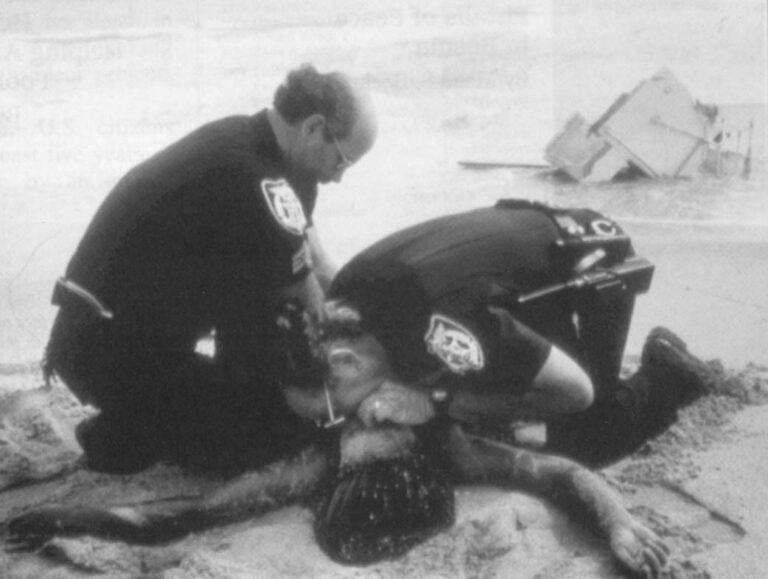

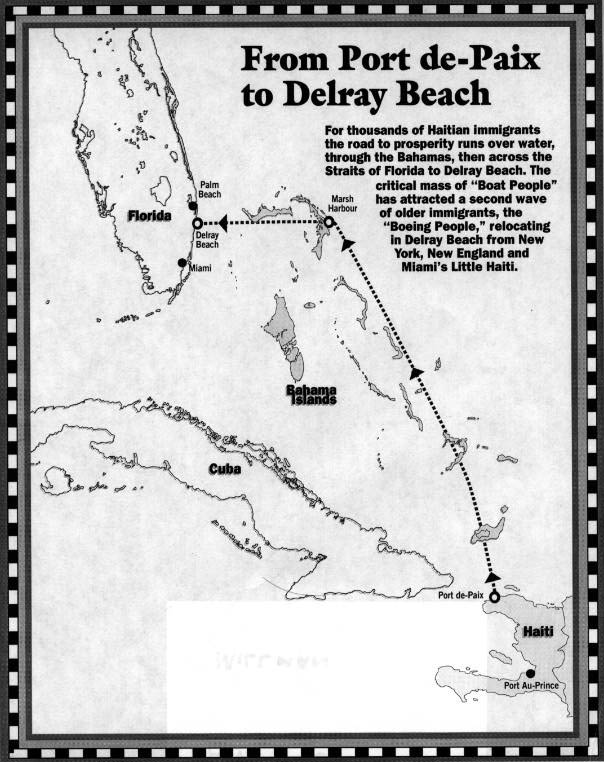

There is another reason the Haitians come: location. Delray Beach lies just forty miles west of the Bahamas across the Straits of Florida. Since the 1880s Bahamians have crossed over to the mainland. In the 1980s the Bahamas became a back-door entrance for Haitian boat people. By 1990, some 5,000 Haitian refugees were living near Marsh Harbour in two squalid refugee camps called Pigeon Peas and Du Mode. Fed up with their own “illegal alien” problem, Bahamians began evicting the Haitians. Many rode smugglers’ skiffs to Delray Beach.

Daniella Henry, now director of Delray Beach’s Haitian American Community Council, recalls the morning drill whenever refugees wandered in. “They knew to come to the office,” she says with a conspiratorial smirk. “Sometimes I let them shower and have breakfast, then I took them to find their people.”

By then the local Haitian zones reflected clear lines of emigration from a chain of villages running along Haiti’s northern coast. “If the man says he comes from Port de Paix, I drop them in Southeast,” Henry explains. “From Leogane, I drop them in Southwest. Someone will know them.”

For thousands of Haitian immigrants the road to prosperity runs over water, through the Bahamas, then across the Straits of Florida to Delay Beach. The critical mass of "Boat People" marsh has attracted a second wave of older immigrants, the "Boeing People," relocating in Delay Beach from New York, New England and Miami's Little Haiti.

If the man came from Artibonite, Henry drove north to Lake Worth, another emerging enclave, or to Jupiter, Mangonia Park, West Palm Beach – all places where Haitians knew someone would know them and find them a job. After a night at sea or on a public beach, they arrived dazed and disoriented. But by sundown many would be in uniform – laundering hotel sheets, scrubbing floors, or busing tables.

Although smuggling continues, the Border Patrol station at Riviera Beach closes on weekends, when most landings occur. Although Floridians decry the immigrant onslaught, their taxes pay Daniella Henry’s salary. The effort to assimilate Haitians includes publishing information in Creole on food stamps, pre-natal health care and AIDS prevention. The Boca Raton Resort and Club, the county’s most exclusive hotel, employs more than 500 Haitians – and provides “Hospitality English” classes using teachers provided at no charge by Palm Beach County’s school board.

Living in Delray Beach, Haitians are Boca’s “good” blacks. That rankles African-Americans. “You see them doing all the jobs we used to do,” says Clay Wideman, an African-American businessman. Wideman admits the Haitians have simply out-competed locals by being more reliable, more energetic and more willing to work cheap. He also admits four of five employees in his beauty parlor are Haitian. Haitians are competing in other “traditional” modes. Boca Raton’s elite Olympic Heights High School used integration mandates to recruit Chamard Lauriston, a 6-foot, 210-pound Haitian immigrant, and all-county linebacker. Against arch-rival Boca Raton High, Chamard faces Donald Jean, another Haitian, the county’s top running back.

While Chamard is making tackles on Saturday (“high, mighty glory,” he says), his home on SW 6th Avenue buzzes with suburban renewal. Stepfather Nicholas Legenord leads a gang of sons and nephews clipping hedges, raking brush and dabbing roof tar. “I bought this house in 1983,” Legenord says proudly, pointing to the tall fichus tree in his front yard. “That was just a little thing when I came.”

Legenord came from Artibonite. He settled in Miami in 1980, working construction by day and restaurants at night to raise the down-payment on a $50,000 fixer-upper in Delray Beach. Legenord acknowledges the welcome has been uneven. “Some white Americans moved away when we came,” he says. “Some of the young blacks still throw rocks at us.”

Kids at the middle school call his 11-year-old, Daniel, “banana boat.”

Haitian immigrants from as far away as Canada and New England are flocking to Florida. Many of the newcomers are long-term immigrants attracted by Delray Beach’s growing reputation as a Haitian-friendly town. They are the “Boeing People” (as opposed to “boat people”), who arrived during the Duvalier Dynasty. They are the doctors and dentists looking to serve Haiti’s expatriate middle class. “The first month I opened, I had at least twenty new patients,” says Robert Victome, a snowbird from Brooklyn who opened Delray Dental Associates last September.

Attending services with Daniella Henry at the Bethanie de Boynton Seventh Day Adventist church, I met several transplants, including Weisner St. Ville, who runs his own screen-printing shop. “Miami is too different from life in Haiti,” St. Ville told me. He bounced from Brooklyn to Miami before coming to Delray Beach.

“I didn’t want to raise my kids in Miami,” explained Kesnel Exantus, another parishioner, who left Little Haiti in 1988.

Haitians are making it in Delray Beach, but they are also making waves. In one neighborhood last fall, 300 residents signed a petition protesting construction of the Emanuel Evangelical Lutheran Church. Practically all the signers were black. They complained streets would be spill-over parking lots, that choir practice and Bible thumping would disturb their dinner. Others said Haitian churches bring crime – accurate to the extent that cars routinely are vandalized during services. The city council voted against the Haitians.

Where drugs had reigned, why protest a church? Haitian services are raucous, says Alberto Busby, an immigrant from Curacao and rector of the nearby Calvary Bible Baptist Church, but that was a pretext. “There are jobs black Americans won’t do,” Reverend Busby explains. “But it gets around ‘your father took my father’s job.’ Or they say Haitians make it hard for American blacks.”

Like all immigrants, Haitians are resented by poorer Americans for not being, or not behaving, poor. As fellow blacks, they are hated for validating roles many blacks, especially Southern blacks, want to forget. Clay Wideman sees a different, deeper problem. “Haitian people are different from African American people,” he says. “They have no fear of the white man. When they apply for a job, they expect to get it.”

When Haitians buy homes in “white” areas, they remind American blacks that racism’s stings can be self-applied.

For Daniella Henry, the conflict between the old African American community and the Haitians is a poignant indicator of progress. “When we first came, white people never made us feel welcome,” she says. “Now the blacks are scared. They think we’re going to take over. Like the Cubans.”

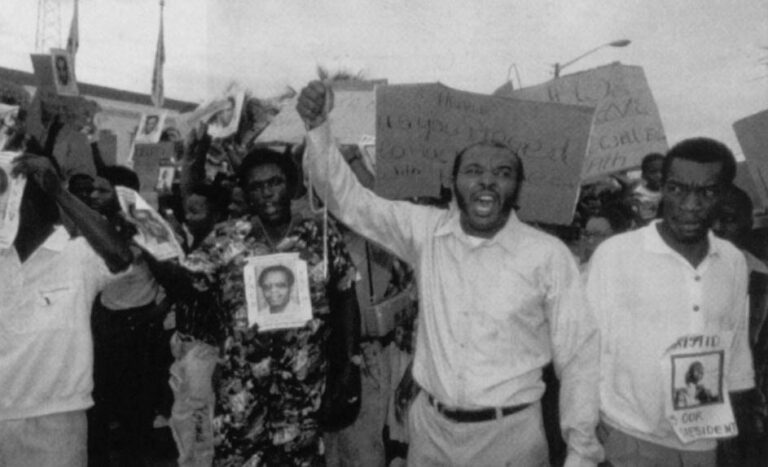

The conflict is now her personal challenge. Daniella Henry plans to run for City Council one day, a post she says a Haitian will win by the end of the century. Since 1994, some 5,000 Haitian immigrants have stopped by her office, seeking naturalization forms. “If just 3,000 vote,” she affirms, “that will make a difference.”

And if they vote with African-Americans, blacks will run Delray Beach. “I want to be the bridge,” she says. “Nobody recognizes the Haitian contribution today. But they will.”

©1996 Joel Millman

Joel Millman, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal in Mexico City, researched Caribbean and African immigration during his Alicia Patterson year.