Dallas, Texas-On a drizzly January morning earlier this year, a crowd of politicians and lobbyists from California jammed into the Good Street Baptist Church, a modest brick building in the heart of Dallas’s black neighborhood. The power elite of the nation’s most populous state had come to pay homage to Minnie Collins Boyd, a small black woman who had worked much of her life as a maid for Dallas’s white families. She had died at the age of 83.

They listened as tributes were read from Texas Governor Ann Richards and former President Ronald Reagan. Back in California a night earlier, Governor Pete Wilson paid his respects during his televised annual “state of the state” address.

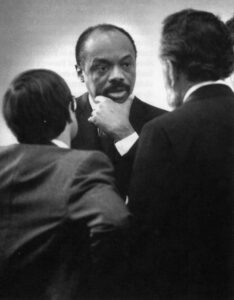

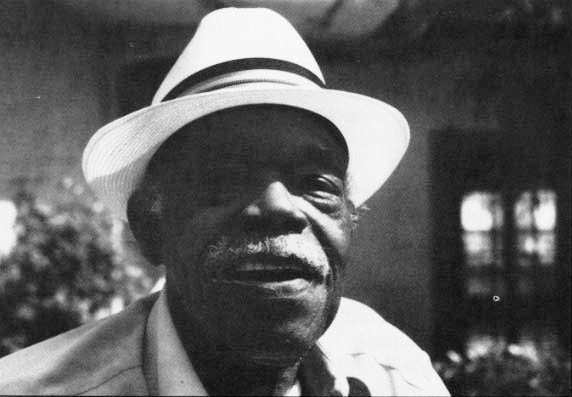

Minnie-as she was universally called by her friends, family and the former president was the mother of Willie Lewis Brown, Jr., who at that moment was arguably the most powerful politician in California and by virtue of that status, arguably the most powerful African American politician in the United States.

He has been elected by his peers seven times as Speaker of the California State Assembly and has wielded power now for 12 years. He has been speaker through the terms of three governors-speaker longer than anyone in the state’s history.

In Brown’s hands rests the fate of legislation and a 0 billion bureaucracy. He masterminds an election machine that has kept the state Legislature and the California congressional delegation in the hands of the Democrats for a decade. He fuels the machine with campaign contributions by tapping corporations, unions and trade associations with business in the Legislature. He had learned his craft as an apprentice of the legendary Congressman Phillip Burton, who had shaped California politics for a generation. Brown has long since eclipsed Burton’s genius with his own.

But Brown is more than a politician. He is a phenomenon. He wears,$2,500 Brioni suits, boasting he tosses them out every year. He drives new Porches and Jaguars. He relishes flouting convention, and has attended parties with his wife on one arm and his girlfriend on the other.

He portrays himself as the last bulwark of liberalism in California. But his harshest critics say he is the master of situational ethics, and even some of his friends wonder if his only guiding principle is keeping power.

With characteristic audacity. Brown mocked his critics by appearing in the opening scenes of The Godfather Part III thanking Michael Corleone, the fictional Mafia don, for a campaign contribution.

Brown’s parties are bigger than life. During the 1984 Democratic National Convention in San Francisco, he rented an entire pier on the waterfront. For a campaign fund-raiser one year he hired a circus, complete with big top tent. Another year he hired the Temptations. This year lie hired Ray Charles, accompanied by the Oakland Symphony.

On the morning Willie Brown’s mother was buried there was only a small Baptist choir at the Good Street Baptist Church.

Those who had come to the funeral of Minnie Collins Boyd caught a rare glimpse of where Willie Brown came from. But to know where he was going, they needed to know from what he had fled.

It cost $7 to bring Willie Lewis Brown, Jr., into the world.

His father paid the fee to Chaney Gunter, a black midwife who delivered him on March 20,1934. He was born in his grandmother’s drafty white clapboard house in Mineola, Texas, a town about 80 miles east of Dallas on the map and spiritually deep in the South.

On the night be was born, the Lawson Brooks orchestra was playing at “the shack”-a dance hall run by Minnie’s brothers. She wanted to go to the dance but Willie’s birth intervened. His father took credit for nicknaming him “Brookie” to tease Minnie. He was to say that he did not even know his name was “Willie” until he was 10.

Willie Brown was born into a sharply segregated world where only the edges have dulled over time.The “Whites” and “Colored” signs are now gone in Mineola, but to this day blacks live in small, sometimes ramshackle houses south of the railroad tracks while whites live to the north in suburban-style homes.

Even in death, blacks and whites remain segregated in Mineola. A chain-link fence runs down the center of the city cemetery. The well-manicured graves of whites are east of the fence while the unkempt plots of blacks are west. If there ever was a headstone for Willie Brown’s grandmother, Anna Lee Collins, it is now gone.

Separate was anything but equal in the Mineola of Brown’s youth.

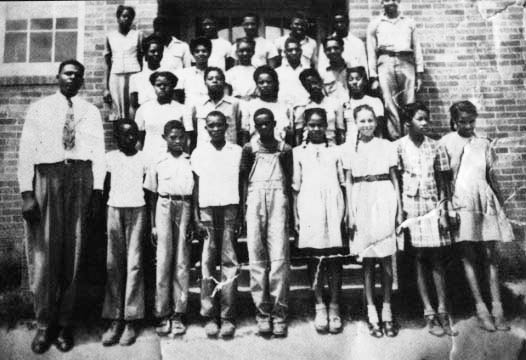

Whites went to schools that were vastly better than for blacks. In 1940-the year Willie Brown entered the first grade Mineola spent an average of $32.40 per white student while spending an average of $9.55 per black student.There was one teacher for every 35 white students compared to one teacher for every 60 black students. The only library in Mineola was at the white high school; there was no public library. An otherwise exhaustive 1949 study of Wood County by the University of Texas did not mention that desks, books and other supplies for blacks–when available were worn and outdated, discarded by the white schools.

Mineola Colored High School was a small red brick building where dedicated teachers taught multiple grades. Years later, Willie Brown had a simple description for the school: “the shits.”

In inter-views over the years, Brown has said his father was a railroad porter who abandoned his family when Brown was a young boy. The full story is a good deal more complicated.

Brown’s father was born in Mineola on Dec. 22, 1908, and he was also named Willie Lewis Brown, Jr. Birth records show that his father-the speaker’s grandfather-was the first Willie Lewis Brown, who was 46 years old when his son was born and died only a few years later, never to know his famous namesake.

Lewis Brown (he dropped his first name), was ahead of his time. He had an extraordinary memory, particularly for names, and mixed easily with whites-talents possessed by his son.

Lewis Brown wanted to go to college and become a doctor, but in those years blacks rarely went past the 8th grade. Lewis Brown moved in with an uncle in Marshall, Texas, and enrolled in a college preparatory program at a local black college. He managed to graduate from high school before his uncle’s fortunes collapsed. Forced to abandon his ambitions, Lewis moved back to Mineola and became a porter at the Bailey Hotel.

Lewis found a better job at Al’s Place, the best restaurant in Mineola, probably in 1931. Years later, Al’s nephew, Art Turk, said that Lewis Brown was the best waiter the place ever had.

“Brown was so unusual,” Art Turk recalled. “He could wait on 75 people without any problems. He learned their names-I don’t know where he’d get their names-but he would.”

Lewis Brown wore a fresh white shirt and white duck jacket every day and polished a pair of distinctive white shoes.

In his off hours, he went “up the hill” to “the shack.”

Today there is a church on the site of the shack. But in the 1920s and ’30s, the shack was combination dance hall, gambling casino and whiskey joint for blacks. It was run by Rembert and Rodrick Collins, better known as “Itsie” and “Son.”

Lewis had known their sister, Minnie, since childhood. But after Lewis returned to Mineola following high school, the two became romantically involved. Lewis lived on Wells Street with his mother, Ella. It was easy enough for him to cross an open field to see Minnie Collins who lived on Baker Street with her mother.

At age 17, Minnie had become pregnant by an earlier suitor, Roy Tuck, whom she married in March 1926. In September she gave birth to a daughter, Baby Dalle. ‘Me marriage did not last. She became pregnant by Lewis Brown, giving birth to another daughter, Lovia, in 1931. A year later she was pregnant again by Lewis, giving birth to Gwendolyn in June 1932. Two years later, she had a son, Willie Lewis Brown, Jr.

Minnie and Lewis never married. Years later in an interview, Lewis Brown said that Minnie’s mother, Anna Lee, did not approve of him. He said that when he went into the Army in World War 11, Anna Lee tried to garnish his wages for child support but the Army rejected her appeal and she blamed him. “She was kind of a tough customer anyway,” he said.

Realistically, Minnie Collins and Lewis Brown stood little chance of setting up their own household during the Great Depression. In Mineola, black grandmothers commonly raised their daughter’s children, sending the daughters off to find work as maids or cooks on the white side of town or in Dallas. Sons lived with their mothers and were expected to find jobs. Census records show that two-thirds of Wood County’s black women worked as maids while two-thirds of the black men worked on farms or in farm-related jobs. And those jobs began slipping away.

During the Depression, farm acreage in Wood County declined by almost halt. Cotton collapsed and with it jobs at a cotton gin employing blacks. By 1945 there were 7,000 acres of cotton left in Wood County; 80,000 acres of cotton had gone out of production. New Deal price supports kept some farmers afloat but did nothing for the blacks who depended oil cotton-related jobs.

Blacks began leaving and Lewis Brown was a part of that exodus. He went to Los Angeles at the invitation of his sister, Idora, most likely in 1937 or early 1938.

Lewis found work as a waiter at a Hollywood drive-in. He then became a porter on a Pullman railroad car before joining the Army at the outbreak of World War 11. He had left Mineola for good.

Now 84 years old, Lewis Brown lives in a convalescent home in Southern California on a pension that is quietly supplemented by his politician son.

When Willie Brown talks about his childhood, he invariably mentions how poor his family was. Compared to whites, his grandmother’s household was indeed poor. But relative to other blacks, her household was on top of the hill.

Her house had electricity and a radio. Uncles Son and Itsie had automobiles. ‘Mere was plenty of food and an extra place for children who wandered in. The minister at church was a regular guest for Sunday dinner.

And Anna Lee Collins owned her home.

“They were some of our Big Negroes,” said Patty Ruth Newsome, who grew up next-door.”They had a little money.”

The household income came from Itsie’s and Soil’s dance hall and their bootlegging business. The brothers sometimes kept their moonshine in tier basement.

A month before Willie Brown was born, Son Collins stood trial on bootlegging charges in Quitman, the county seat. Court records show that Soil’s lawyer told the jury that the police had caught him with someone else’s whiskey and he was acquitted.

Itsie Collins, who now lives in a San Francisco retirement home, said in an interview in February 1993 that he and his brother opened the dance hall using money Itsie had won gambling in the oil fields east of Mineola.

“Lots of colored people had oil (money) and they didn’t know what to do with that money,” be recalled. “When the East Texas oil field opened up, I made my headquarters in Kilgore.

“I made so much money there I was scared to go to sleep.”

The two brothers hired traveling black orchestras for their dance hall, dished up hamburgers and kept a supply of moonshine hidden under a trap door.

Anna Collins’ household had another source of income as well. Minnie was working as a maid for a Mineola white family, making $3 a week. She brought the money home to her mother.

When Willie Brown was young-he could not have been more than four or five years old-his mother left Mineola for Dallas, probably not long after Lewis departed. Minnie could earn $15 a week as a maid in the big city and she brought most of it back to her mother on weekly trips home. She became pregnant in Dallas, giving birth to James Walton, her last child, in January 1939.

World War 11 was nearly a disaster for Anna Lee’s household.

In an interview nearly 50 years later, Itsie Collins said he was paying someone to keep from getting drafted so that he could keep the dance hall open.

Eventually, he said, someone in the Selective Service put a stop to it.

“I was paying to stay out of the Army,” he said. “But some white guy got onto what was going on. Oh, they had a big fight.”

Itsie Collins had reached the point where the only legal way for him to stay out of the military was to get a job in a war-related industry.

“They told me I had to work or fight.”

He decided to go to California. His decision was to have far-reaching consequences, not just for himself and his family but for all of California. It was because of Itsie Collins that Willie Brown would eventually move to California.

Itsie got a job in the Bethlehem Steel shipyard in San Francisco at 3rd and 20th streets south of the financial district. He worked at the shipyard until his 38th birthday in 1943, the day he was ineligible for the military. Itsie quit the yard and took up where he left off in Mineola-running a gambling joint, only this time in the wide open city that was San Francisco.

In Mineola, Anna Lee Collins was making ends meet with the money her daughter brought home from Dallas on Thursdays, her day off, and with whatever income her daughter’s children could pick up. In the summer, Willie Brown and his sisters would pick berries at a farm 15 miles south.

Willie was fastidiously neat. He had two pairs of khaki pants and painstakingly ironed them. He ordered clothes out of a Sears catalogue.

Mother and grandmother admonished the children to do well in school. Willie turned out to be a superior student. He loved to read and talk about what he had read. He was quick with figures and words.

As the war wound to its conclusion, an event occurred still remembered vividly by blacks who were old enough. Willie Brown, only 10 years-old, remembers little about what started the trouble. But the aftermath seared his thinking forever.

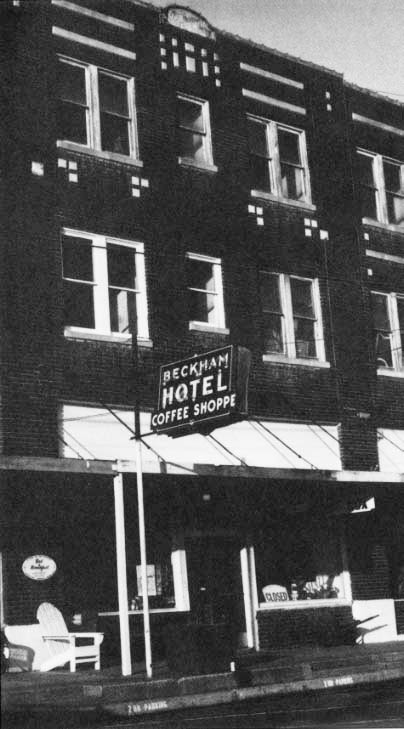

On the night of July 5, 1944, James Bonner Christie-a white truck driver who went by “I.B.”-came looking for Listress Jackson, who was black. Christie claimed Jackson owed him $50 for a car. At around 11 p.m., Christie went down an ally to the kitchen door where Jackson worked at a cafe next-door to the Beckham Hotel.

When Jackson stepped outside, he was cornered by Christie, according to court affidavits. “We have got you now,” Christie told Jackson.

Robert Crabtree, another black man who was Jackson’s father-in-law, stepped outside when he heard the commotion.

Crabtree was knocked to the ground. A scuffle began and when it was over, J.B. Christie-the white man-lay dead, his throat slashed with a kitchen knife.

Crabtree and Jackson were charged with murder. (In May 1945, Crabtree received a five-year suspended sentence while Jackson was given a seven-year prison sentence).

In the days following the killing, the Mineola Monitor gave only a hint of more trouble. “Because of the high feeling Wednesday night-still rampant Thursday morning—officers rushed the prisoner to an undesignated out of county jail.”

Young white toughs roamed the black neighborhood shooting at homes. They torched Crabtree’s house. They posted signs on trees that said: “No “n…..”s in town after sundown.”

Marcus McCalla, who was five years older than Willie and lived around the corner, said the well-to-do whites in Mineola warned the toughs to bypass the houses of their maids and servant.

“They were protecting their help,” said McCalla. “You see, the rich people didn’t go for that. They were the ones that kept things from getting out of hand.”

Patty Ruth Newsome, living next door to the Collins household, remembered the fear most of all.

“I know I was so afraid,” she said. “Mama would make us come in before dark and lock up because it seemed like they would kind of go from door to door.”

And a 10-year-old black youth repeated his tale over and over for years to come.

“For many days and weeks any car coming down the streets, if you were black, you got as far away from the roadway as possible because one of the retaliatory processes engaged in was to knock you off the roadway with the car-hit you,” Willie Brown said in an interview years later.

Asked if he was ever hit, Brown replied, “Hell no. I stayed off the roadway.”

But young Willie worried his grandmother and her worries deepened as he became a teenager.

Willie had a hankering for hanging around “uptown”—the small commercial center in Mineola. He shined shoes at a barbershop. The white men thought it great sport to throw a quarter in a spittoon and make him fish it out. It was among Willie Brown’s most bitter memories of Mineola. But he was drawn uptown all the same.

He would always be uptown and we were always afraid for him,” his sister Lovia said. Her grandmother, she said, “didn’t want anything to happen to Willie, but Willie he just said whatever come to his mind.”

Once, one of his sisters recalled, a white man asked him, “Say. junior, what time is it?” using a pejorative term reserved for black males. Willie did not respond. The white man asked again. Finally Willie Brown Jr. snapped, “You guessed my name. Now you can guess what time it is.”

His sisters wondered that he wasn’t beaten up. His grandmother was positively alarmed.

In later years, Brown said he came to California to seek opportunity and the big city life. But it is also equally true that his grandmother wanted him out of Mineola for his own safety.

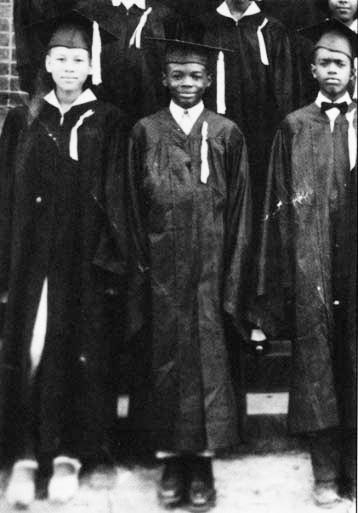

Brown graduated second in his class at Mineola Colored High. In later years, he joked that the only “B” he received was for “comportment.”

Texas held little promise for Brown. He was “colored” and had graduated from a “colored” high school and that made him ineligible for the University of Texas. He could have gone to an all-black college in Texas, but the black colleges turned out good teacher-, and good farmers but not much else.

Brown, who has always been physically small, was a natural born lawyer, but he stood about as much chance of becoming a great lawyer in Texas as he did of becoming a fullback for the Texas I,Longhorns. In 1946, when a survey was taken, there were 7,701 white lawyers in Texas and only 23 black lawyers.

In May 1951, soon after he graduated from high school, he packed his khakis and a few belongings and boarded a train bound for San Francisco. Soon after crossing the state line out of Texas, the “colored” signs came down in the train and Willie Brown could go anywhere he wished.

His Uncle Itsie picked him up in San Francisco. The first thing Itsie told him to do was get rid of the khakis. They would not do in San Francisco for the life he was about to lead.

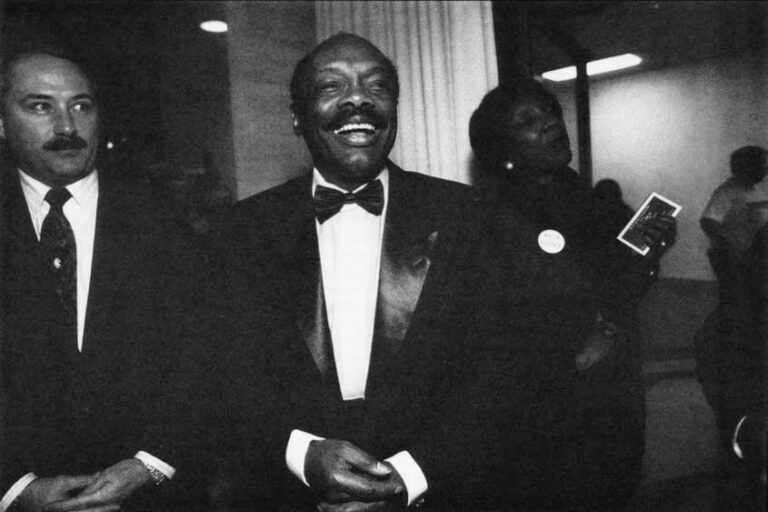

Forty-one years later, on .the night before she was buried, the family of Minnie Collins Boyd held a wake at the Good Street Baptist Church. A half-continent away from his adopted domain, Brown talked of the spirit of his mother. Like her, he had beaten the odds. Like her, he had enjoyed life to its maximum.

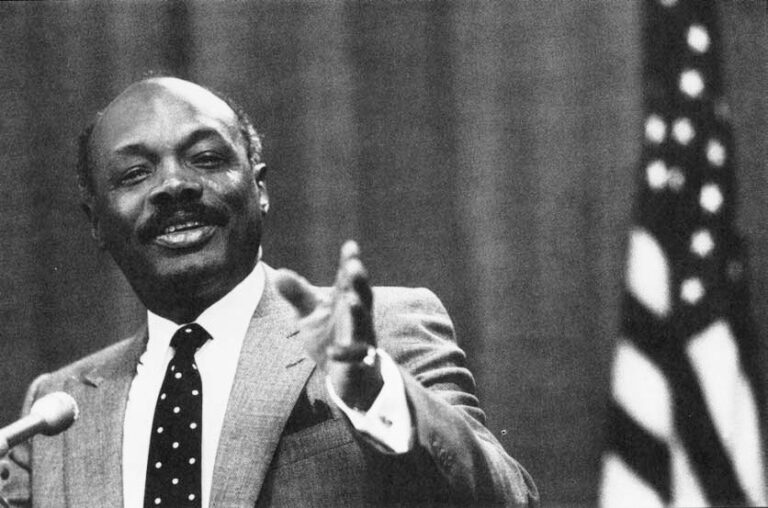

Brown had succeeded beyond the expectations of nearly everyone in the room that night but himself. Against great odds, he took legislative office by beating a Democratic incumbent in a 1964 primary. As a relatively unimportant legislator, he was at Robert Kennedy’s side in the days before Kennedy was killed in a Los Angeles hotel. Growing in stature, Brown electrified the 1972 Democratic National Convention with a speech cinching the presidential nomination for George McGovern. Brown became a required stop in California for all would-be Democratic presidential nominees. In 1988, Brown served as national chairman of Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaign.

But his career has its share of twists. In the 1960s, he was consigned to the farthest reaches of legislative oblivion for opposing the state’s legendary Speaker, Jesse Unruh. In the 1970s, Brown tailed twice to be elected Speaker largely because fellow African-American legislators didn’t trust him. Brown finally won the prize in 1980 by making a deal with Republicans that left Democratic front-runners in shock. Republicans rationalized that they had elected a weak Speaker, but they, too, ended up in shock. After meeting Brown in June 1992, presidential hopeful Bill Clinton cracked that he had met the real “Slick Willie.”

For a few hours on a dank January night, Brown’s rivals set aside their differences at the Good Street Baptist Church to honor his mother. But Brown was not the only center of attention that night. Holding court at a table during the wake at the church’s social hall was 87-year-old Itsie Collins, and Brown took great delight in introducing his uncle to visitors. “I suspect he only survives because neither place want,,, him,” quipped Brown.”He is the man I’ve patterned my life after more than any other.”

©1993 James D. Richardson

James Richardson, a reporter for the Sacramento Bee, is examining the life of Willie Brown.