BATON ROUGE-Brent Cadle, 16, drops onto all fours and looks up at his even younger audience. “First, we never walk; we crawl,” be says. The 40 children and a few parents sitting on the floor around him hug their knees and watch, rapt. No crankiness or yawning although it is 10:20 at night and some have been traveling for several days.

“Second, what do you do when a policeman puts his hand on your head?” Cadle, a strong looking All-American type wearing shorts and a baseball cap with the brim facing back, surveys the room. Silence. “Do you keep going?” More silence. “No and you don’t hit his shoe. You don’t touch him. You back away and you go around him.” Some kids’ mouths drop open. “If one person did that, it wouldn’t make much difference because he would just follow you, but imagine if 10, 20, 30 of us do it. They won’t be able to keep up.”

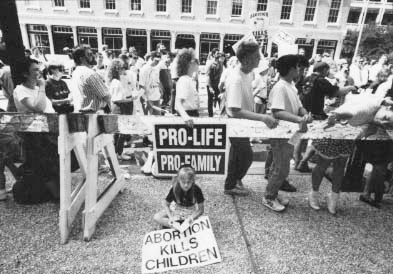

This training session, run by national members of the anti-abortion group Operation Rescue, prepares children to break the law. As more children become involved in Operation Rescue demonstrations aimed at closing abortion clinics, these training sessions have become commonplace. The stated goal is not to get arrested but to prevent pregnant women from entering all abortion clinic and to “save babies.” This session takes place at Hosanna First Assembly, a charismatic, non-denominational congregation in a comfortable suburban area of Baton Rouge. The congregation strongly supports anti-abortion activism and welcomed the Operation Rescue members from across the country.

Baton Rouge was the third city visited this year by Operation Rescue, following Buffalo and Milwaukee. Although the consensus is that the group is losing steam, there have been almost as many arrests last summer as there were last year in Wichita, the group’s most dramatic victory. One controversial change in tactics, however, is that leaders now encourage the participation of children. In Milwaukee, 353 of those arrested, or 25 percent, were children.

“Any protest group has to get maximum mileage out of its efforts,” said Robert Louden, associate director of the criminal justice center at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and a 21-year veteran of the New York City police department.

“One way to do that is to have your wife, your grandmother and now your daughter or son-people you think the police are less likely to arrest-on the frontlines. It means the police are faced not just with a protest, but the added burden of handling 5, 6, 7, 8-year old kids,” he said.

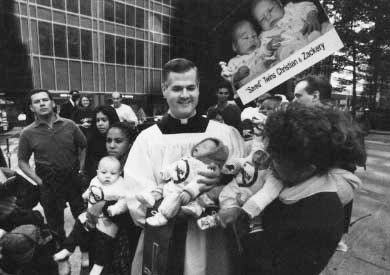

As fewer adults blockade clinics-because they face heavy fines if they violate probation orders-children are taking their place. They have formed Youth For America, a children’s arm of the Rescue movement. Its core group of about 50 members come from families with longstanding ties to Operation Rescue or similar groups such as The Lambs of Christ. Some of the parents are ministers and their congregations fund their pro-life work. Others, like Tom and Linda McGlade who act as chaperons for Youth For America, own their own businesses. The McGlades install sound systems ill churches. When they have enough money, they travel to Operation Rescue demonstrations with their children.

Most of the children come from families of modest means. They live in the suburbs of Florida and southern California and in working-class communities in the rust belt: Cleveland, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh. They are Presbyterian and Baptist; Pentecostal and Episcopal and Roman Catholic. Most practice a charismatic form of faith that involves dancing, clapping, and speaking in tongues.

As Louden and police officers across the country emphasize, more lenient rules govern children’s activities, making their involvement a boon for the Rescue movement. When children break the law, often they are not fined, nor are they detained. That means they can return to the clinic and block doors again. Brent Cadle, who along with Marisa Vittitow, 16, and Jae McManus, 16, led the childrens’ activities in Baton Rouge, was arrested 11 times in Wichita alone. Vittitow was arrested 16 times in Milwaukee. McManus said tie’s been arrested so many times, he has stopped counting.

The kids act as a magnet to local children, most of whom have never been involved in anything more than occasional Saturday morning pro-life picketing. In Baton Rouge, about 50 local children join the core group. Only a few of these children agree to risk arrest, but they stand with the core group in prayer. Members of the core group are the veterans, the “in” crowd, the leaders.

For Marisa, Brent and Jae, blockading clinics is training for their future. When Marisa finishes high school she wants to continue her rescues. Mary children say they want to join Missionaries to the Preborn, an itinerant offshoot of Operation Rescue that blockades clinics around the country.

The involvement of children represents Operation Rescue’s bid for a hold on the future. Even more important than providing bodies, the children’s presence carries moral weight. Without ever needing to Litter a slogan, they make Operation Rescue’s point that only time distinguishes the child in front of the clinic from a fetus in the womb. ”They (fetuses) are our spiritual brothers and sisters,” says 11 year-old Min McManus, Jae’s sister. Their father videotapes for Operation Rescue.

0n Tuesday evening, the second day of Operation Rescue’s week in Baton Rouge, children cluster in the lobby of Hosanna First Assembly, sitting on the floor or on benches. “This is like a pro-life reunion,” says Jennifer Cadle, 10, who frequently travels with her brother, Brent, and her father to rescues. There is an air of summer camp to it. But the talk is of their last blockade, whether a doctor went out of business, where they were arrested, and who stayed in jail. Many of the children spend at least half the year on the road.

“I was in jail for 24 days in Buffalo,” says Jae McManus answering a question from a girl whose family regularly attends Hosanna but has never participated in a rescue. There is a moment of silence. Jae is one of the children’s heroes. Several reach and touch his arm, a sign of encouragement, wanting to be close to someone so dedicated. “He’s a rescue fanatic,” explains Min.

In the Operation Rescue lexicon, the word “rescue” is both noun and verb. Clinic blockades are called “rescues.” A rescue can take a few hours or it can lake weeks. Even if not one woman is stopped from entering a clinic, the event is called a rescue and the participants describe themselves as “having rescued.” The verb “to rescue 11 describes attempting to block clinic doors, but its meaning is expanded for children so that they can consider themselves rescuers even if they don’t risk arrest. “Rescuing is praying and it’s being in front of the clinic door,” says Jae.

Many of the children come without their parents and when they do, they often have to pay Operation Rescue or whichever of the rescue groups is organizing the demonstration. Usually the arrangement is for several children from an area to get together and come with a local minister or adult. About half the children who traveled to Baton Rouge seemed to have come with friends. For six weeks in Milwaukee, the average cost was $600, but the amount depends on how long they stay and where they come from. Brandy Wyar, 15, of Frederick, Md., says she sent a letter to relatives and members of tier church asking them to sponsor her summer of rescue activities. “I got $800 in a month and some letters back saying ‘we can’t support you because this causes violence,” she said.

Many of the children in the core group of Youth For America are home-schooled. It is the only practical way to teach children who are away from home so much of the year. Mothers (to much of the teaching, either in the months when the children are home or between clinic sieges on the road. Those who attend parochial or public schools find the institutions unsympathetic to their schedule of rescue activities. “They failed me this year for being with Operation Rescue so I’m going back to do ninth grade over, said Toshia Harris, a 16-year old from Cincinnati. She wouldn’t mind being taught at home, but her parents work full time and dropped out of school at early ages. Her father, who completed 6th grade, works in a machine shop; her mother who graduated from 7th grade, cleans rooms at a local hospital. Toshia has come to this rescue with friends.

The kids’ favorite reading is books on spiritual warfare, a genre that would be unheard of in most schools. Jae especially likes “Piercing the Darkness,” by Frank Peretti. It is the story of how satanic and new age cults take over a small town and with the help of the ACFA (American Citizens Freedom Association, a thinly veiled substitute for the American Civil Liberties Union) attempts to close down a Christian School by accusing its headmaster of spanking a pupil. In writing style it resembles “The Exorcist.” He says the book inspires him when he prays in front of abortion clinics. Other favorites are the Bible and, for 10-year-old Jennifer Cadle, “Pilgrim’s Progress,” the l7th century allegory of a husband and wife’s journey from the corruption of this world to heaven.

In daily life as in literature, Christian teachings are the framework. The children pray before arriving at abortion clinic protests. Once they arrive at the clinic, they pray again, sing hymns and listen to preachers as well as attempt to Stop women and staff from getting through the door. Dinner (served at a church) is followed by a three-to four-hour service which include charismatic expressions of religious ecstasy. People run through the aisles, clap, dance and speak in tongues. Jennifer Cadle, whose father is a conservative Presbyterian minister, says that what she like best about traveling for rescues is 11 seeing different churches: Catholic, Baptist, charismatic.”

The most colorful part of each day’s church service is the testimonials by guest speakers. One of these is a talk given by a mother and daughter team about a mother who tried to abort her daughter and failed. Many of the children said they had heard it before, but liked it so much they decided to listen to it again instead of going to play in the church lobby. Mother and daughter describe what life has meant to them and how hard it has been to accept each other. The daughter, Heidi Huffman, 13, is a rising leader in Youth For America.

On the first night that Operation Rescue arrives in Baton Rouge, the testimonial is replaced by a showing of Hard Truth, a film about abortion and rescue. With semiclassical music as its soundtrack, the film shows shot after shot of late term-aborted or miscarried fetuses. They are completely recognizable as soon-to-be-born babies but are mangled, bloody and terrifying. A hand holds up a severed head, the camera focuses on torn fetuses. Inter-spliced are shots of Operation Rescue members being dragged away from clinic doors by stony-faced policemen. This is the call to arms. Although the film lasts just nine minutes, it feels like an hour.

The aborted fetuses in the movie bear little resemblance to those aborted in most clinics where Operation Rescue demonstrates. More than 90 percent of abortions are so small and early in development that the naked eye call not distinguish an arm or leg. But those pictures of early abortions are not shown.

Most parents sit in Silence through the film and their children watch it with them, their eyes glued to the screen much as they would be for a horror movie. “He needs to know the truth,” says Mary McGuire, a Baton Rouge resident, as explanation of why she let her seven-year-old son see it. The film is shown twice during the week and video tapes of it are on sale in the church lobby every night along with a selection of other pro-life, videotapes. “It makes me very upset,” says Toshia. “But it is the truth.” Brandy agrees: “They should show it across the nation,” she says.

The sermon that follows, and most of the sermons throughout the week, will ring the theme that abortion is a blood sacrifice, a symbol of the struggle between good and evil. “The devil is in town and there’s blood running in the streets,” says Rev. Keith Tucci, the director of Operation Rescue National. The children nod somberly.

“Too many kids have died. We are determined to stop tile child killing, and we will do what we must do to stop tile child killing. In the spiritual realm, what is happening is that we are withdrawing our permission for child sacrifice,” he says.

At 2:30 a.m. on Thursday, the alarm goes off in the Motel 6 room where Jae and Min are staying with their father. In minutes they are dressed. fly 3 they join the other rescuers in the still summer night in the parking lot of the Sheraton Hotel, which is just a few minutes walk from the abortion clinic. The children’s part is not yet certain and they cluster around Linda and Tom McGlade, the couple from Bradenton. Fla. who act as the children’s chaperons. Everyone has a votive candle. When they are lit the symbol of these people as Christian lights in the darkness will be complete.

Rumors run through the crowd: the police have machine guns, they have brought in guard dogs, the abortion clinic is closing. None are true. The children crane their necks to see. Cincinnati preacher Joe Slovenec stand in the middle giving instructions. He has a soft voice but a preacher’s ( and politician’s) ability to project without shouting. He looks like a street fighter, muscular, a bit of a pot belly, closely cropped hair.

“Joshua to the left, Rescuers to the right. I want you 15 across, put your hands on the shoulders of the person in front Of you.” The children quickly fall in line. Jae looks over his shoulder to make sure everyone is following orders. (Joshua is a reference to the biblical character who blew down the walls of Jericho. In Baton Rouge the “Joshua Phalanx” is a group of musicians, banner bearers and dancers. The walls they are trying to blow Down are those of the abortion clinic.)

Slovenec tells people to light their candles. In the humid air, the flames stand straight. His first instructions are to the 75 pastors who are leading the procession. “Each of you guys will go up to the police. You will say ‘Let me through because they are killing children in there’ and of course they won’t and you will say ‘My name is so and so. I’m a pastor’ and you will proclaim whatever is in Your heart. The idea is proclamation. We’re making a proclamation to the church today.”

The crowd advances on the clinic, with the children not far behind the pastors. They are wearing t-shirts that say “Turbo Christian” and “I Survived The American Holocaust.” It is still pitch black but the candles and street lights show a line of police and on each side of the line, hundreds of clinic defenders. Many of these wear lace-up black leather boots, cut-off shorts and sleeveless shirts. The frontlines seem mainly to be drawn from radical gay and lesbian groups. Some of the women, who wear t-shirts saying ‘Abortion on Demand and Without Apology’ carry high-pitched whistles which they blow in the ministers’ ears. They shout and jeer in rhyme: “Racist, sexist, anti-gay, born again bigots go away.” And later, “Pray, you’ll need it, your cause will be defeated.”

One of the clinic defense leaders, Susan Farren, hovers around Tucci as he kneels, praying. “Do you know what an illegal abortion sounds like?” she asks. Tucci does not answer; like a Muslim in prayer, he is completely abased on the ground. Farren shrieks, a high, terror stricken sound. Tucci doesn’t move.

The local children who have joined up for this rescue look shocked. They have never seen or heard anything like this. ‘They look pretty evil,” says Blair Giffin, a 13-year-old from Abida Springs, Louisiana as he watches the pro-choice forces. “They look like they are angry all the time. I think they are afraid of us.” Min nods. “Look at that man with a ring in his nose, how can lie blow his nose? It’s disgusting,” she says.

Lea Vittitow, a slender girl of 11 with brown-blonde hair and all-American looks, stands still, watching. One of six children, whose family are members of Missionaries to the Preborn, she is an old hand at rescues. ‘They are just filled with evil. “The power of Satan is all behind them,” she says looking at the line of clinic defenders. “All you have to do is look in their eyes and you see (lie evil behind it. A lot (of them) will do anything for the blood of a child.”’

These are statements of fact for her. The clinic defenders are murderers, little different from the hated doctors who perform abortions; they are enemies in the spiritual war. Their flaunted homosexuality-many wear t-shirts saying Queer Nation-add fuel to the Operation Rescue myth that people who perform, defend or undergo an abortion are tainted by the biblical curse of barrenness.

By 9 on Friday night, the children have given up on the sermons. They drift around the lobby of Christian Fellowship Church and talk among themselves. Several have a certain wistfulness. They have not yet had a chance to rescue. Tomorrow, Saturday, will be their biggest day because it is the weekend and local working people will be able to come. But for most it will also be their last day and they will have to return to less adrenalin charged lives.

Min and Jae are torn about whether to risk arrest. For Jae it seems to be an especially hard decision. “I do not like to rescue: but I am called to rescue,” he says. But his mother has forbidden him to do it. Min explains that their mother, who is divorced from their father, believes abortion should be legal. The children only became involved in the Rescue movement in the past three years when their father became involved. “She doesn’t like any of us going to pro-life rallies. She doesn’t want us to rescue. I feel kind of mad at her because she has no right to run our life,” said Min.

“My stepmother is very pro-life, just like my Dad. But every time she wants to rescue she’s pregnant. She has two children and one coming,” says Min. Since coming to America from Korea to be adopted when she was five, Min has moved several times, first with her parents and then with her father after her parents divorced. She has only a faint memory of her birth mother in Korea. She recalls being on a bus that was taking her to the orphanage and seeing her mother run away through a maze of traffic because “she was sad to leave me and she didn’t want to see my bus going away,” Min says. Her tone is matter of fact but she looks about to cry.

For some of the children, traveling with Operation Rescue gives them a sense of family. They believe in what they are doing fervently, perhaps in part because adults who treat them with warmth and kindness, believe it. Many of the children, when asked who their heroes were, mentioned people in the rescue Movement. Brandy Wyar, 15, said Rev. Joe Foreman, who founded Youth for America and Tom McGlade. Katie Hahn, 14, it cheerful girl with wavy brown hair, mentions Rev. Johnny Hunter, the only black preacher in the Operation Rescue leadership, and his wife, Pat. She traveled here with the couple, who are from Buffalo.

Pro-choice activists who track Operation Rescue say some of the children are drifters clinging to anything that gives order to their lives and others are normal teenagers. Kathi Hudson, a longtime pro-choice activist who has attended almost every major Operation Rescue event, says some have a history of being abused or coming from families with alcohol problems. “I’m not sure that these kids are so different from teenagers in the 60s who ran away from home and hung out in the Haight,” she says.

As a leader in Youth for America who has been rescuing for four years, Marisa Vittitow is realistic about the kids’ backgrounds. “In the pro-life movement we get kids who are misfits, outcasts in their schools. We have kids who come from abusive situations, who don’t love themselves,” says Vittitow. Her own family life seems relatively happy. She is one of six children and for I he past year the whole family has been involved in rescuing year round. She names her father as one of her heroes and Pope John Paul as the other.

“Oftentimes they come and they see our families and just want to be part of us. The rescuing is secondary,” she says. “They see how much love we have for one another and the unconditional love and they want to be accepted. And they are so starving for affection, they’ll do anything for it,” she says.

A the sky lightens on Saturday, the Sheraton parking lot again fills with Operation Rescue members. The plan is for the children to lead the rescue-a conscious tribute to the biblical passage from the book of Isaiah prophesying the peace on earth that will herald the Second Corning. ‘The wolf also shall dwell with the Iamb and…a little child shall lead them.”

A separate contingent of adults is dispatched to the clinic’s back gate ;is a diversionary tactic. Of the more than 50 children there, 20 plan to risk arrest. Linda and Tom McGlade hover near the children but let Brent and Marisa run the show. “OK everybody is supposed to go limp to the paddy wagon,” says Brent.

“When you crawl, spread out as much as you can.”

The children hold hands and begin to jog towards the front of the crowd. Linda McGlade jogs alongside keeping her eye on them. There is talk of police, brutality. “These kids are solid,” she says implying that nothing will faze them. Marisa and Brent nod their assurance to her. Min and Jae are walking with the prayer support contingent.

As usual, the rescuers in the front go right to the police barriers. The police stand in a line a bit beyond the barriers. A police helicopter hovers behind them. Paddy wagons with wire over the windows line a nearby street.

Instead of standing, praying and trying to engage the police in conversation, the rescuers kneel. The police seem to relax a little. As the sun rises, the demonstrators hold out their arms and begin singing:

I have decided to follow Jesus

Though none go with me

I will follow

No cross before me

No world behind me

No turning back

No turning back.

This is it. The children are running. Several of the adults pull back the police barrier; the children rush through; adult rescuers follow; the police surge forward. At the clinic’s back gate, rescuers are surging through too. Linda McGlade stands by the barriers shouting at the children, “Go, go, go.” The children are running into the lines of police, getting pushed, shoved. Jae grips his Bible, leans over [lie barricades, tears in his eyes. He is with them in all but body.

Somebody shouts to Min’s father and the other Operation Rescue photographers “Abuse, police abuse. Over there, film it; film it.” Four people need hospital treatment. The worst is a South Carolina woman whose ankle and knee were fractured when the police told them to hit the ground. She said she was pushed into the concrete. Later a police brutality case will be filed involving nearly 100 of the rescuers.

In minutes the rescue is complete. The children mass against the gate. It will be impossible for anyone to get through this entrance. The police stand with their arms crossed. No one is going any further.The sun is high and hot, the humidity rising. Sweat rolls off the rescuers’ faces; they are sitting arm in arm), making the heat almost unbearable. People pass them water.

After some hours, an agreement is reached with the, police. No patients will be brought through that entrance.What they do not know and would not believe is that some of the staff and women patients came in last night while [lie rescuers sat in church, praying.

©1993 Alissa Rubin

Alissa Rubin, a reporter for Congressional Quarterly, is examining abortion in America.