If one only had an aviator cap of thin, fine leather, with earflaps and a chin strap that one snapped in a gesture of importance while settling into the feed trough, er, cockpit, one could shout, “Contack!” (an important aviator word) with a tone of authority. And with a deep-breathed HrrrrRRRMMMM! the propeller would whirr. And one would be lifted, transported on silvery wings, over the barn lot, the pasture, the summit of Mt. Mitchell and uncharted lands and seas beyond.

But one had to have an aviator cap.

Floyd Wilson was a little boy in Yancey County, N.C. in the era of bi-planes and barnstormers. He was born in 1918, the year the war to end all wars came to a close and the flying aces came home.

Their stories were the new stuff of heroism and adventure. Worn-out tales of barehand fights with bears and wildcats paled beside accounts of dogfights with the Red Baron. Every kid in America wanted an aviator cap. Floyd Wilson set out to get one.

Now, this bit of transfiguring magic would cost about a dollar, and dollars did not grow on many bushes in Mount Mitchell’s shade. Yet some people did (and some still do) pick up a modest living from the woods. One of the commercial staples was galax, its lustrous and long-lasting leaves being then and now a mainstay in floral arrangements.

There were some older boys and men among Floyd’s kin who made a little money at what they called galacking. Floyd decided he would get in on this bonanza.

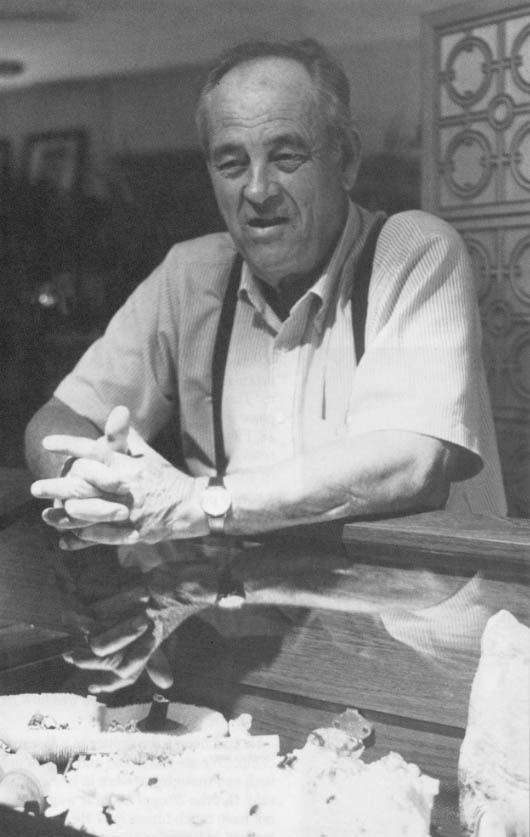

“At that time there weren’t very many cars,” he says now, leaning on the glass-topped showcase of his shop in Micaville, N.C. where he sells jewelry and no galax. “They’d load up a wagon, take what they’d need to camp and go way back up in the woods.

“My mother cut me some fatback and fixed me up some pancake flour. We took the wagon and went up Lower Creek and made our camp. That night they made the fire and got to telling them old ha’nt tales. Old ghost tales. You know, people really believed all that, back then. I listened at’em till my hair was standing up.

“I laid there and didn’t go to sleep until about four in the morning, and in just a little bit they all got up, got me up and we cooked our breakfast and took our oat sacks and straggled out over that mountain. We pulled galax for about a week.”

Not pausing to be picky, he filled his sacks with bug-nibbled, brown-specked, malformed leaves and a few healthy green ones. When the galackers got home, he remembers, “My mother helped me tie my bundles, the way we were supposed to. When the buyers got through culling’em, they had thrown out all of mine but a thousand–worth 20 cents.”

Floyd didn’t get his aviator cap. “But you could get these little old Western books for a nickel. They every one had Texas in ‘em. I could just see that old green grass a’wavin’.”

Economically there was not then a lot of promise in Yancey County. As Floyd puts it, “The Congo was far advanced to this place before Roosevelt.” So when he was 18, Floyd and his friend, Wimpy, went in search of greener grass. They joined the Army.

“They put us on this old jalopidated bus and they took us down to Ft. Bragg. It was a ‘pourin’ the rain when we got there. Wimpy says, ‘You know, we’ve played hell. We’ll never see home again.’”

“But oh, I had a good time!”

Floyd saw lots of places, including Germany, where he was wounded in World War II. When he did get home. his big concern, as it has been among Southern highlanders for generations, was how he was going to stay.

He had been a fire-fighter in a forestry camp; “We ate loaf bread and sugar-cured ham and thought we were in heaven,” he said. But the 20 cent an hour wage did not have much future in it. He had worked in the mica mines, one of the few local industries. But his interest in minerals was taking a very different turn.

Floyd Wilson was an artist. Not long out of service, he entered the Penland School

of Handicrafts, just a few miles from home, and began to study gemstone cutting and jewelry design. As has seemed to work best for highland entrepreneurs, he drew upon a resource close to home. In this case it was his own lifelong observations.

Now in his workshop in his house on the Burnsville Highway he holds out for scrutiny a droll, jewel-eyed gold bug on the palm of his hand. “When I grew up,” he says, “you had to find things to occupy your mind. When I started making these things I didn’t have to worry about how a frog or a spider looked when it was moving. I knew it.”

His work is in the Smithsonian Institution; he has been profiled in the National Geographic. Shoppers from around the globe come to look at the dazzlers in his showcase. He and his wife, Shirley, travel to Arizona when they wish to. They visit Florida. They live at home.

The latter was not come by without determination. “I had to come up with these rolly-eyed creatures,” says Floyd, or “I’da had to leave here.”

Floyd is one of about 650 members of the Southern Highlands Handicraft Guild, the largest of several craft guilds and cooperatives operating in the Appalachian region. He observes that the guild wears a sharper business edge than it did in his younger days.

“It was born of, to give progress to, the true old mountain crafts. There used to be these old people bottomed chairs with hickory. There were the forges and blacksmiths, and the ladies that made quilts. Now it’s gone to the commercial end.”

The commercial end involves a vast diversity of sophisticated products from primitive-style furniture through exquisite blown glass, fabrics granny never wore, porcelains, sculpture and fine jewelry. The crafts-folk and artists who bring them forth are not necessarily native, and likely did not learn their trade at grandpa’s knee.

Jane Murto, who sells crafts in a shop in Harper’s Ferry, observes, “We have people here with master’s degrees, making toys.”

Even the craft movement itself had some less-than-homespun origins.

Back in the mid-1880s, railroad heir George Washington Vanderbilt rode into the mountains of western North Carolina in his private railroad car, called “Swannanoah.” Only about five years before, in one of the most dramatic and astonishing railroad epics in history, a team of convicts had literally pushed, tugged and all but carried the first locomotive over unfinished track through Swannanoah Gap, east of Asheville.

One could safely have predicted the almost immediate effect of the railroad on settlement, commerce, tourism and industrialization in that area of the Appalachian South. No one would have made book on the continuing impact of George Vanderbilt-just another rich Yankee who loved mountains.

Possibly on first sight, Vanderbilt decided to create for his wife and offspring a comfortable (or so he must have thought) dwelling on a farm carefully planned for self-sufficiency. Maybe to preclude fussing neighbors, he quickly bought 100,000 acres for the site of the house, which he called “Biltmore.”

To make sure the place was nice Vanderbilt hired the finest stone masons in Italy to come and show the local workmen how stonework should be done. He hired Frederick Law Olmsted to design the landscape and fine gardeners from abroad to care for the grounds and greenhouses.

He hired Gifford Pinchot and Carl Schenck, two of the world’s most renowned foresters, to restore the surrounding maltreated woodlands to a virginal appearance–and in doing so, established scientific forestry as a vocation in America. He hired the best agriculturalists, the finest weavers, woodworkers, artisans of all sorts.

All of these endeavors would, out of necessity, involve local help. Which, significantly, the experts had to train. And when Biltmore was finished, a “farmhouse” on the order of the Palace of Versailles, the Vanderbilts turned much of their attention to the furthering of fine craftsmanship, especially among the young, in the land where once it had thrived and would thrive again.

Thus was fueled a craft renaissance in Southern Appalachia, and its impact on the culture is still growing.

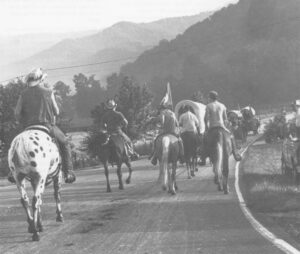

Something else that surged in that era and never lost momentum was tourism. There may be no record of when the first flatland settlers came riding on whatever they could, or walking, in search of a breath of relief from a scorching summer, or the sound of rushing water, or a lofty vantage point.

But it is sure that from the day of the first pioneer cabin with smoke coming from the chimney and the smell of cornbread baking on the hearth, there was someone with a hopeful look and a dog-eared map knocking at the door.

Stage coaches brought tourists to the airy heights of Carolina, to the healing springs and hospitality of the Virginia highlands. Deeper inland settlement and the railroad, improved roads and automobiles opened the floodgates.

By the late 1980s, according to a study reported by the Appalachian Regional Commission, tourism was providing well over 300,000 jobs and adding between three and four billion dollars annually to the economy of the Appalachian region.

And yet, as Sen. Robert Byrd of West Virginia noted in a 1990 discussion of the issue, “Here in our mountains lie undeveloped, or underdeveloped resources for recreation and relaxation.” And that is true; a traveler on the narrow little side-roads of the Virginias, and throughout the region, is awed by the miles and miles of lovely solitude. Part of the charm.

Others point out that most jobs connected with tourism are in the service area. Such jobs tend to be low-paying and seasonal and offer few chances for advancement.

Something about this sticks in the native craw; it recalls a line in a letter written years ago by a low-country matron, recently moved to the hills. The exasperated lady said of her newly-hired help, “These people are untrainable as servants!”

Cautioners add that burgeoning development may create some construction jobs but the contractor and most tradesmen will come from somewhere else, and take much of the payroll with them. Growth will burden local water, waste and health facilities and law enforcement agencies. The necessity of higher taxes and the natural result of rocketing land values can put buying-and sometimes staying-financially out of reach of local people. This is true even for those blessed with new jobs waiting tables and keeping grounds.

But then, tourism is basically clean. No foul smoke, no seeping chemicals. It is sometimes culturally enriching, if one does not count the giant hot-pink waterslide–Visible From Seven States!–or Weirdo’s Waxworks of Gruesome Stuff ‘n Things.

In areas where retirees settle, community life can be enormously enriched, along with the tax-base. In Salem, S.C. outland retirees, among them physicians, scientists, professors and top-management veterans of business and industry, tutor students at Tamassee-Salem High School in math and science and language. Additionally, they become the students’ friends. In Hendersonville, N.C,, volunteerism by elder come-latelies is a celebrated phenomenon.

Sharing the landscape with tourists is a trade-off, in the view of one Waynesville, N.C. farmer: “It’s what we have; we better learn to live with it.” Learning to live with, and from, what one has is the highlander’s primary survival tactic.

Since Avery County, N.C. has become, over recent decades, the Christmas tree capital of the world, most upland farms have a few rows or several sprawling acres of manicured young trees. Fraser firs, cedars, Scotch and Virginia pine have displaced tobacco, grain and cattle in some places as the major cash crop. A cash crop no one brags on but some surely cultivate is cannabis sativa, a useful hemp (good for fiber and oils) that various persons, including a recent Kentucky candidate for governor, have declared should be legalized, and tax levied on the considerable income it is known to bring growers. Cannabis/ hemp/marijuana does very well in the damp mild climate of Southern Appalachia and contributes immeasurably, lawmen lament, to some isolated economies.

So do other unusual crops. Red Alderman farms near the New River at Todd, N.C. His major crop is evening primrose. That’s a modest yellow-blossomed wildflower that grows along ditches and roadsides.

What does he grow it for? The seeds. To grow more primrose? Only in part.

“We send the seed to LaRoche Pharmaceuticals, in England. They’re the largest pharmaceutical house in the world. They extract the oil from the seed. The oil is used in the U.S. in cosmetics, in the rest of the world for nutrition and in England also as a medicine.”

Alderman, who grew up on a farm in central Florida, came to North Carolina to teach earth studies at Appalachian State University. Fascinated by the unsung properties of wild plants, he began Watauga Herbs, a root and herb brokerage in Boone, where the venerable Wilcox Drug Company was already the world’s major supplier.

Scavengers from across the mountain region shipped or brought Red sacks of ginseng-in its increasingly rare wild state worth around $165 a pound, and yellowroot, bloodroot, boneset, borage, maypop and other such medicinals, which he then sold to pharmaceutical houses here and abroad.

The business grew large and he decided to leave it. He and a partner divided it. “She took over the herb company. I took the agricultural part. We had recognized that there are economically important botanicals being harvested from the wild and we decided to put them into cultivation. The next thing was to work out the methodology.”

There are plenty of people, Red says, who want to make a living on their land. So when he runs out of acreage of his own, he contracts others to plant a small bed, or a hundred acres, of borage, echinacea or cultivated ginseng.

“I’ve changed my business,” he says. “I used to have a lot of people working for me. I was too much involved with ‘business’. Now I operate out of our home. I use a fax to communicate with anybody in the world. You don’t have to have the appearance of a business when you have the telephone and the fax machine. It would be very difficult without those things.”

Red came of age in the era of the “back to the landers,” many of whom returned to town sadder and maybe no wiser. Why?

“They couldn’t recognize that they were part of this world. Some had the skills but most did not. We are at the mercy of the elements and of people who are not honorable, or who have needs in conflict with ours. We have to understand, too, that there is a process of culturalization. We think we can live lives of voluntary simplicity–and then something comes along that we WANT!”

“I have had to recognize that I am very much a part of this modern world. That nothing is accomplished without stress and strife. I recognize that I have need for more than to just make a living.”

“What I want to convey to people is that it can be done.”

©1992 Dorothea Jackson

Dorothea Jackson is a freelance writer in Six Mile, South Carolina who is examining the economic fate of the Southern Highlands.