Photos and article by APF Fellow Dorothea Jackson

There is a flat room-sized rock that sticks out into a pool in Big Santeetlah Creek, which borders Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest in Graham County, N.C. The place is called Rattler’s Ford, a name that more likely came down from a Cherokee family that lived here than from a snake.

The Snowbird Reservation, a collection of Cherokee properties with disjointed boundaries, no commercial district and a largely Cherokee-speaking, history-conscious populace, is close by. In the summer, pickups jammed and rocking with young Cherokees disgorge in the parking area near the creek. The revelers hit the ground running for the rock; it is their jump-off place into this pristine and mysterious stream.

Not one bit does the legend of nocturnal business here dampen these festivities. If (as some witnesses declare) ghostly warriors still come shouting, crashing through the night woods and splashing through this icy current, if indeed the sweaty-smelling spirits do surround and swarm upon this rock in pursuit of ancient enemies, no one begrudges them their occupation.

The phantom marauders may be dead, but it would seem they don’t intend to leave. One stays in this part of the country by any means one can.

The will to hold tight to an Appalachian homeland has long driven the imaginations and the labors of the living. A paycheck economy is hard in a place that has been precluded, by its up-and-down geography, from equal industrial and commercial opportunity. It is hard on people whose trust had been in angels, earth and elements instead of banks and Wall Street.

That some do not make it and have to leave is evident in the tables of out-migration. During the 1980-1990 census period, Graham County, a nearly matchless beauty spot rimmed on three sides by mountain ranges, including the Great Smokies, and on the fourth by Nantahala Gorge, lost population.

The loss was only 21 people, or 0.3 percent, from the 7,217 count in 1980. That is deceptive; all along the banks of the streams, up the mountains with the panoramic views, new cabins and houses of substance have been built, and new people have moved into them. How many local folk have left, so evenly balancing the scale, has not been determined.

Jobs declined by 116 in this timbering and light manufacturing dependent county. Still, the per capita income did rise, hitting, $8,842 – half the national average – in 1988.

Whatever the actual exodus from Graham County, North Carolina it was minuscule compared to the 14,666 (29.4 percent) loss front McDowell County, West Virginia; McDowell was only the hardest hit of 34 counties in the Virginias and Kentucky that fell by 10 percent or more in the latest census figures.

Overall, in the decade past, the Appalachian region showed a 1.6 percent gain in population while the nation gained 9.8 percent. In the Southern highland area monitored by the Appalachian Regional Commission, only the Georgia and South Carolina upland populations grew across the board.

That would be predictable; both are on the highlands’ southern rim, a largely gentle, mellow land beloved by retirees and some industries. Access to cities accounted for the biggest growth; Gwinnett County, Georgia., a lightly rolling suburb of Atlanta, grew by 111.6 percent in 10 years and nearby Dawson and Cherokee Counties gained by 97.5 and 74.5 percent.

And while West Virginia lost as a whole, its eastern panhandle is a dramatically different story. Berkeley County, centered by Martinsburg, grew 26.7 percent over the past decade.

“Basically, we’ve had agriculture and tourism,” says Susan Walter, who directs the Shenandoah Community Health Center in Martinsburg. “Now we also have industry and outlet malls. Good highways have been an inducement; we have a lot of clean, high-tech industries moving in…” The Appalachian dream.

Commuters go out of the Martinsburg area to Frederick and Hagerstown, Maryland, and to Washington, D.C. The railroad depot parking lot fills early in the day at nearby Harper’s Ferry. If peace and beauty would not suffice, “The taxes here are very low,” says Mrs. Walter.

Tourism throughout the mountains has been a mixed bag, as far as helping to hold the home folks. Sevier County realized the largest spurt of growth in eastern Tennessee. What’s there? Gatlinburg, home of the world’s longest traffic jams. And Lord-a-mercy, Dollywood!

Yet in Virginia, Bath County was the state’s biggest population-loser, showing a decline of 18.1 percent. That, despite its scenic charm and famous thermal springs, a natural drawing card.

Bath County’s major employer is the palatial old spa called The Homestead. where a family can easily drop several hundred dollars each luxuriating day – if a family has that much to drop. Given the nation’s current economic climate, fewer and fewer do. “People are leaving,” says Diane Hunter of the county administrator’s staff, “because there isn’t any work here.”

It’s the almost universal highland problem.

For those who stay, ingenuity must provide. Here are the stories of some who survived here because of it.

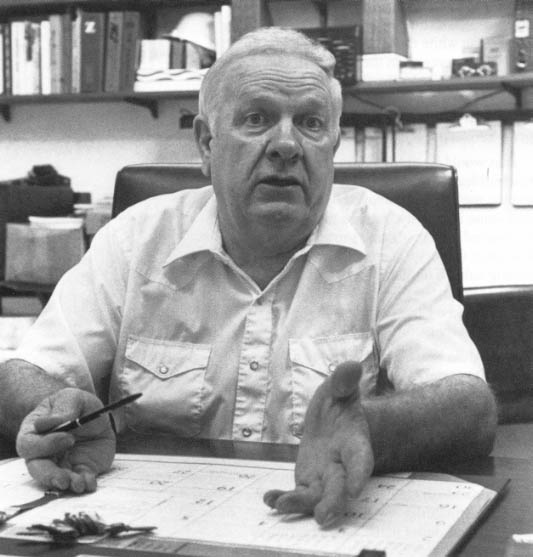

Ray Vance Miller had it. Miller is not one to brag but he is said by neighbors to be (at the least) one of the richest people in Yancey County, North Carolina. Should one go to his neat plain cinderblock “Ray V. Miller Enterprises” office in Pensacola, near where the Barnardsville highway becomes dirt, Miller will explain some things he does.

“We make these,” he says, holding up a little nameplate made of granite. “And we make these… (A calling card holder.) My boys and me fix up old cars. We fix up old houses too. We like to collect old pictures of Yancey County.

“We find something to do. You do that, if you want to stay here.”

What Miller found, just out of high school, in the early 1950s, was a job with a gifted older friend named John Robinson, who fixed radios and televisions. Robinson had made precision instruments for bombers during World War II. When the war was over, he simply came home.

“John should have been the richest man in North Carolina,” Miller says, “but he just fixed things for people that had no money. He paid me $2 a set to fix a TV or a radio. He’d add 50 cents to the customer, if he thought they had it. He was a fine man; he didn’t need me but he said he was afraid I wouldn’t be happy if I had to move to a big city.”

Barely out of his teens, Miller was getting ideas about sending pictures over a telephone line. He actually saw it work while he was briefly in Cumberland, Maryland. He worked on a plan and tried to get local or nearby financing to develop a cable TV system. Nobody with money paid him much attention.

He married his sweetheart, Mary Ann McPeters, and they went on a two-day honeymoon, paying their way with coins out of a coffee can. She was making $15 a week at the register of deeds office. He worked at least two jobs at a time. They had a dream. They began to save.

“We started with five dollars. When we had $540 and a 1949 Ford that was knockin’ so bad I was afraid the engine was about to blow, we decided to go to Alaska. I had a cousin there. Then we decided to go by way of California; we wanted to see how the movie stars lived.”

Of course, things that cost money happened all the way to California. When the adventurers arrived in Hollywood, nearly broke, they stayed at a motel run by an instant friend from Winston-Salem. “He said, ‘I’ve been to Alaska. You’ll freeze your tails off.’ He got us the paper and showed me the help-wanted ads.”

Miller immediately got a job as a TV repairman. Very shortly he went out to fix a woman’s TV and there was nothing wrong with it. “Maybe it’s the cable,” the woman said.

“The what? Where is it?” said Miller.

“On the roof,” the woman said. Sure enough, he climbed up and there it was. And he was able to see what was wrong with it. And he climbed down, and in a triumphant mountain voice, was able to tell the cable company that its handiwork had malfunctioned.

“What do you know about cable?” the dubious manager said. It turned out, says Miller, that there were only two men in the Beverly Hills area who did know anything about it. And he was one of them. He went to work for that cable company; shortly he was the manager, and a stockholder. When the company was sold, not long after, he says, “I was never going to have to work for anybody again.”

He had his own cable companies after that. “At one time we had 14 systems. I’ve had 39 franchises and 57 systems. I was the first to have live programming and to sell advertising on cable TV.”

Miller and his wife knew, from the day they started west, that they were coming home as soon as they had the money to buy a farm at Pensacola. They gave themselves 10 years. In 1965, they came home and bought the farm. They have three grown children and offices in Myrtle Beach, S.C. and in Florida.

“Years later, we did get to Alaska,” Miller says. But they live at home, in the Highlands.

Miller’s relief that he would never have to work for anyone again came of a conviction that lies deep in many hearts. The corporate idea of the “good” employee is often perceived – and not without evidence – as one who puts the company’s values above one’s own.

Bill Poland and his wife, Jenny, live in a setting of dreamlike tranquility on the south fork of the Shenandoah River, at Front Royal, Virginia.

From their yard they can see the place where they say the river dies. “You won’t see a frog, a bug, a bird,” Poland says. Gaseous bubbles come up from the bottom of the placid stream. Stinking liquid, “green as poison,” came up from neighborhood wells, Poland says, when there were neighbors. The water was not only unfit to drink, but he believes it was responsible for human illness and death. He points to where homes used to be. downstream, where some neighbors became ill, some died.

Across the river are the industrial waste lagoons where it seems the pollution originated. A little farther in the distance is the deserted Avtex rayon plant where Poland worked for 17 years, at the last as maintenance superintendent.

Avtex was operating despite 2,000 state and federal pollution violations, and almost as many safety violations, when the state revoked its discharge permit and the plant closed in November of 1989. In one incident, a worker had fallen into a vat of boiling chemicals and died.

Poland was no longer working at Avtex when it closed. He quit in 1981. “I was walking on a catwalk across a vat of hot chlorine. It was about 140 degrees in that room, and all of a sudden it occurred to me, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’ I gave two days’ notice and quit.”

He also became vocal about the health risks and environmental damage. Friends had cautioned him about quitting, worried about how he would make a living. Jenny remembers, “Anyone who took a stand against the company took a lot of abuse from people who were worried about their paychecks.”

Poland bought some tools and farm machinery, repaired what needed fixing and started a construction, farm and garden equipment business. “We knew we’d probably be lean for a couple of years, but we did three times the business we had expected,” he says. Three years later, the business was taking more of their lives than they wished to give it, and the Polands sold out. He now works as maintenance supervisor at a nearby nursing home.

The plant across the river remains closed but still, Poland says, “We kind of fear what’s already in our systems.” One thing that is not in his system is regret. “What price is a job? You sacrifice a few lives for jobs? Not me.”

Rebecca Allen learned how much the environment lagged behind jobs as a community priority when she encouraged her Canton, N.C. sixth graders to read and think about the effects of pollution, which most of them had been seeing and smelling all of their lives.

It was risky timing. Champion Paper Company, the area’s major employer, was under stern scrutiny by the EPA because of pollution in the Pigeon River. The State of Tennessee was threatening to sue because the river carried Champion’s waste across the state line, just as winds had carried the stench over the neighboring mountains for decades.

Champion’s rebuttal was that more than 9,000 jobs would be threatened if the EPA’s mandated clean-up was enforced. “Our principal told us in a teacher’s meeting that our kids were to write letters to EPA in favor of Champion,” Allen says. “I just couldn’t do that.”

She had asked that her students be allowed to attend an upcoming EPA hearing in Canton as a field trip. Her request was turned down, she says. Then, “I made these little posters.” She holds up one she saved: it says, “Don’t Muddy the Waters with Emotion.”

“I put them up on the class bulletin board on Monday,” Allen says. “On Tuesday, I had the principal, the county superintendent and the assistant superintendent at my door.” She remembers that a deputy sheriff waited in the hall.

The superintendent told her she would have to take the posters down, or he would do it, she says. “Well, of course that sealed it. I said, ‘Well, I guess you’ll have to.’ And he did. He took them down right in full view of my students.”

“I worry about that,” she said. “Will they think that if they speak out, somebody will come down on them?”

At the end of the year, Allen says, she got a bad evaluation. “They didn’t fire me. They gave me a third grade and moved my room.” With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, she filed suit. Eventually she settled for an apology, which she says she never got.

Allen and her husband Bob are both Canton natives. “Both of my grandfathers worked for Champion; my aunt was secretary to the CEO,” she says. Her stand set her apart from friends and kin. Her son and stepdaughter were in high school; her husband was the assistant football coach. “I didn’t want what I did to affect them. I decided I would just go over to Asheville and get a job.”

What happened the next year, now four years ago, was that her husband got a better job as head coach at Andrews, in a rich green valley about an hour west of Canton. “On his coattails,” she says, “I got a job teaching eighth and ninth grade English.

“We landed into something wonderful here,” she says. “We love it. I love the school; I love what I’m teaching. I tell my kids, “Don’t leave your brains at the door…”

When he was a very small boy, Robert Thomas Long of Jefferson, N.C. hit a hard place. It took him 43 years and a miracle of friendship to get back what his family had lost.

Long lives in a modern house with such a commodious sprawl that a man in town gave directions to “that apartment house.” His two grown daughters live with him. Sometimes Mexican farm workers live with him. Visitors of all sorts stay there.

When he had his 81st birthday last summer, there was a big tent out in the yard with tables and chairs for the overflow crowd. There were about 300 well-wishers from 15 states.

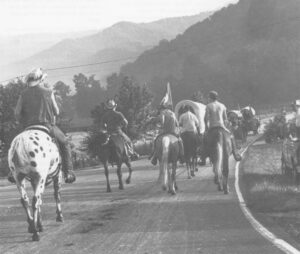

“One couple rode up the mountain and fell out,” Bob says. “They’d never been that high before.”

Long’s father was born in slavery in Ashe County, N.C., on the eve of the Civil War, the son of a black slave mother and a landed white farmer. When the elder Long was grown, his father deeded him a big tract of land in the Laurel Springs area of Ashe County and built him a house on it.

By Long’s early recollection, it was perhaps the biggest farm in a county in which, as is generally true in the mountains, there were very few black people. “When my daddy died, he had about 500 acres of land. We had all kinds of farm tools and two teams of mules. We lived like people!”

Until his father died. “Do you know how it is when something dies in the field?” Bob Long says, with a thump of his cane. ‘Buzzards come!”

One of the first visitors to come to “sympathize” with the widow was a white lawyer with a paper in his hand. “My mother was very young; she didn’t venture out like some women do. She was a mother and a housewife,” Long says.

She didn’t know what to make of the “mortgage” the lawyer showed her. She did understand by the time that he left, though, that since she had no money to pay the “debt,” she and her children were about to be homeless.

“I was eight years old,” Long says. “When we left there, we didn’t know where we were going to spend the night.” They moved into an old, abandoned house. “At night my mother would gather us around her like little chickens and pray.”

They made a garden; they worked for people. “There was no Red Cross to help us,” he says. “My mother never got a check – we just lived.” In his teens, Long followed an older brother to West Virginia to work in the mines. The days he didn’t work, he went to school.

Yes, it was true, he said, that black people tended to draw the toughest jobs in mining, “The dirtiest, the most dangerous.” Once the roof caved in and caught his leg; he still walks with a cane. That did not defeat him. It gave him courage to study mining safety regulations and take the test as an inspector, which he passed. “You can imagine how that set, when I came around as the inspector,” he says, smiling wryly.

But in all things, Long’s nature was to be honest, to be fair. He earned respect, made friends.

He had a wife and four growing children when he got a letter from another white lawyer back in Ashe County. “Lawyer Austin said, ‘Your daddy’s land is going up for sale. Come bid on it.’

“I told him that I couldn’t. I didn’t have a quarter. We didn’t make no money, you know. In the mines, we didn’t work half the time, and what I did make was going to take care of those children. Lawyer Austin said, ‘Come on.’

“I came down, and he said, ‘Go ahead and bid. I’ll help you.’ Lawyer Austin knew that a lawyer robbed my mother. He was a good man. He helped me. I bid and paid $500 down.

“Well, it went on and on and they never give me no deed. It turned out that they couldn’t give me one because they never had no deed in the first place. Lawyer Austin said, ‘Go get on that land. Live on it. Build a fence. Pay the tax.’ My brother did the same with another piece of it. I raised tobacco, I had cattle, sold timber.”

With ownership legally established, Long eventually would do something far more profitable. On a slope with a view of the New River Valley, he put in underground utilities and a water system and began selling homesites to the cities’ well to-do.

But there was another chasm he and his family first would have to cross. In 1962, when they first came home, there were no schools in Ashe County for his children. So, he says, “I had to go back to West Virginia so they could finish school.”

They came home and worked the land on the weekends. As his sons and daughters finished high school, they enrolled in colleges in North Carolina and got jobs. At last, they were home to stay.

Ten years ago, Long’s wife, Sally, died. Otherwise, he says, “Life’s been sweet. God ain’t made no better place than Ashe County…”

It is just home.

©1992 Dorothea Jackson

Dorothea Jackson is a freelance writer in Six Mile, SC, examining the condition of the Southern Highlands.