Photos by Marc Geller

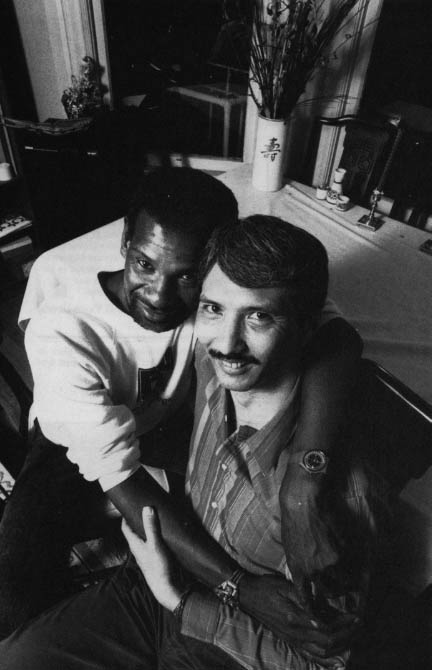

Derek grew up in Washington, D.C. in a strong, stable dual income family with a number of brothers and sisters. He was trained as an accountant and made rapid progress; by his late twenties he was named head of payroll operations at a bank. Nights and weekends he took classes and worked part-time as a massage therapist. Derek’s lover, Gunther, a Swiss national, was a highly paid professional whose family he had visited in Zurich. One day, more than four years after the two had been coupled, Derek’s mother spoke to him about his future. “Why don’t you and your sister buy a house together?” she asked. “You’ve both got good jobs, you’re single, it’s a good investment, and your father and I could help with the down payment.”

Derek began to consider the idea, musing about how he and his corporate-lawyer sister would get along. And then he shook himself.

“Morn, I can’t buy a house with Liz. If I were going to buy a house with anybody, it’d be Gunther.”

“Gunther could be gone tomorrow,” she answered.

“And so could Daddy.”

Gunther was not unknown to Derek’s mother. He had brought him to family gatherings, even to the annual Easter afternoon dinner. No one had ever been rude to Gunther, but there was no denying that he precipitated a measure of discomfort, for generally Gunther would be the only white person present.

Derek’s account of his family relations is typical of what homosexual couples say they experience as they try to integrate their conjugal families with their birth families. Even if their parents and siblings are not openly hostile, they are often completely unable to acknowledge homosexual mates. Perhaps they find it too painful to imagine their brothers and sons in the intimate details of daily mateship, or perhaps because they lack even the visual imagery to make it real.

Since their conversation about buying a house, Derek says his mother has not made the same mistake-and, he adds, she always asks about Gunther. They see each other on a weekly. if not more frequent basis. He is geographically close. He has intimate conversations with his mother and one sister. They are present for one another even if that presence includes recurring aggravation.

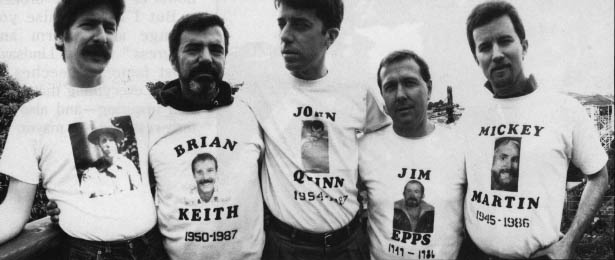

By contrast, San Franciscan Reed Grier frequently speaks at professional meetings about his experience in burying most of the members of his family.

“Why did you put yourself through all this torment?” others Would ask him. “Because we’re family,” he would answer. ‘This is what you do for family.” The five men who were all in some way connected to Grier’s devoted friend and former lover, David, constituted his primary family. Beyond them were two or three straight friends he has known since college and secondary school, people who have sustained their commitment to each other through critical life crises, people who, as he puts it, “were there for each other” just as surely as he feels his blood family has not been there for him.

Now, as he begins to get the first intimations that he too may not escape the disease that took the rest of his gay family he has begun to explore the pain and inadequacy-the “dysfunction,” he says-of parental family while at the same time proclaiming the passion and spirituality of his constructed family.

‘The key word,”he says, “is support. Emotional, practical support. And why? Because we care about each other. We have meaning to each other. Not instrumental meaning, as in ‘this is where I can get help,’ but unqualified support because I care and I take care, they care and they take care. Because of my experience in this overly individualistic society and with a [blood I family that was dysfunctional, I tried to create my own tribe, my own sense of communal solidarity with other people.”

Derek who seems to have negotiated a comprehensive life within both his families, and Reed, whose dysfunctional blood family sent him on a quest to construct a replacement, are common, perhaps archetypal gay,-,. Still more, they seem emblematic of the anguished search for a place of personal solidarity haunting Americans at large in the late 20th century. As any number of sociological reports and blue ribbon commissions have demonstrated, the inherently footloose character of American We combined with powerful economic and demographic pressures have rent our families asunder.

When Alexis de Tocqueville made his monumental study of Americans’ ongoing struggle over individualism, morality and democracy in the 1830s, he too located the most troubling torments in our need for and discomfort with family solidarity. What fascinate(] Tocqueville about the new American democracy was the relationship between “attachment” and morality. In their rapacious advance across the, frontier, the Americans had left behind most of the attachments which their European cousins relied upon for their sense of station and identity. Kinship, religion, class. geography: all these told the Frenchman or the Englishman who he was and how he should behave.

As they decimated the native inhabitants, these transplanted Europeans lived devoid of any monuments to psychological or moral location. Often residing beyond the pale of institutional law, the family alone offered refuge from the frantic, rugged individualism that became the half-mark of 19th century American life. Tocqueville worried about the ability of the family to carry so much weight when there was so little beyond faith and neediness to sustain it. Only among the women, whom he identified as the carriers of moral strength, did he see a counter force to the cut-throat male world of commercial and career ambition. To the women he ascribed nurturing roles through which they passed on values of interdependence, Christian virtue and civic good. It was the women who preserved and exemplified the highest of 19th century virtues, sacrifice an(] unselfish love. Through the preservation of those values of care and nurture in an acknowledgedly patriarchal family, they maintained, Tocqueville believed, the abiding foundation upon which democratic, civic life was built. Take them away, shatter the family as the last point of social stability, and the moral basis for civic democracy would disappear.

Tocqueville’s fear for the Americans was that their hyperactive individualism, their compulsion always to take to the road and invent their identities anew, would leave them bereft of a civic base. “I have seen the freest and best educated of men in circumstances the happiest to be found in the world; yet it seemed to me that a cloud habitually hung on their brow, and they seemed serious and almost sad even in their pleasures.” They seemed, he wrote, a people who “clutch everything and hold nothing fast.”

Luna was born in Havana, but left for Miami when he was a small child. Gilberto, his boyfriend, was born in Miami, in Little Havana, the enclave of Cuban refugees which vies with the real Havana as the global center of Cuban cultural life. I met them both on Mother’s Day after they had prepared a least in tribute to their two mother,,. In fact, of the dozen gay contacts I’d been given in Miami, all but one were with their parent,,, celebrating Mother’s Day-and his mother had died six years earlier. Nowhere I had ever been had I seen such close ties between gays and their families, a closeness made all the more remarkable by the fierce conservatism of Cuban Miami.

We sat on old chairs drinking beer in the front lawn of the house where Luna lived with his mother. A few feet away his uncle dozes on a couch inside the enclosed front porch.The uncle, a drawn little man who speaks no English, lives on the porch an(] appears frequently oil local radio stations agitating for new assassination campaigns against Fidel Castro. He doesn’t talk with Luna about Lima’s sex life. Luna, who calls himself a leftwing anarchist doesn’t speak to uncle about Cuba. Overhead jets roared us into periodic silence on their takeoff path from Miami International Airport.

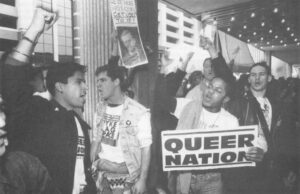

“He was an older man. Cuban. And he was a top,” Gilberto reminisces of his first male lover. Gilberto is 22, sandy-haired, blue-eyed. A close-cropped goatee tickles his chin. A turquoise ear ring dangles from his right ear. His voice is a little camp, a touch fey. He could pass as a Queer Nation foot soldier in New York or San Francisco.

“Somehow I think that they brought over that stigma that somehow you are not gay if you are a ‘top.”‘ Once you are a bottom, “that makes you a queer. And you are like lower in status than a top man.”

Gilberto does not consider himself a “top” or a “bottom.” He has, he says, distinct sexual tastes, but his sexual positioning doesn’t define his sense of gender, of masculine and feminine roles, as it has throughout much of Latin and Mediterranean culture where almost any man is permitted to have sex with other men so long, as he is in the “top” or penetrator’s role. In Mexico, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Peru and especially in Brazil, such “straight” men have long kept discreet homosexual liaisons with boyish inmates who were their “bottoms” and who behaved as silent mistresses.That is the stigma of the old country that Gilberto’s first lover brought over with him. I might have expected other biases from his large, extended family that would have made it unthinkable for him and Luna to lay out a ladies’ luncheon spread, for there was no doubt in anyone’,, mind that (lay that these two men were lovers. Instead, and particularly among Gilberto’s elders, Luna has been taken in as a member of the family.

Toward the end of the Mother’s Day afternoon, several of Gilberto’s cousins arrived, tough, straight, roustabout guys, men Gilberto calls Cuban rednecks, macho men who are always off without their wives, hunting and fishing.

“Well, you got to go spearfishing with US, man,” they’d tell him. “We got a boat.” More talk of what a great time they all have on the boat follows. Then one of the Young cousins-the most redneckish, Gilberto says-draws him in close.

“Like, you disappear! We got to stick together. cause, well, we never see each other anymore. Why don’t you hang out with us anymore?”

“I just sort of go quiet,” Gilberto says. “I figure, he doesn’t know how to track me. cause I’m gay. [But I it’s like, ‘You’re our cousin, and we use to do things together when we were young, and there’s no reason for that not to happen now.”‘ Would he like to hang on to that inherited place of Butch family camaraderie? Would he go?

“I don’t know,” he answers, drifting into visual memories of past adventures. “I really enjoyed hanging out with my cousins before. Going out and getting all muddy. Going fishing. Scaling the fish. (Then a little campy.) Getting fish guts all over my hands-the whole hutch scene. (Then back in regular straight talk Speech.) That’s fun to me, and I miss doing that, cause I don’t find too many people in the gay culture that want to go do that.”

More than Mother’s Day devotion, which borders on gay Latino stereotype, Gilberto’s mixed attachment to his tough guy cousins captures the complexity of his own relationship to family. he hopes to make a household with Luna if their own relationship continues to grow. he would like them to live in a mixed neighborhood of straight Cubans and gays (where now and then he could borrow a cup of sugar from another gay couple). Yet he is also deeply afraid of being beaten, or worse killed, possibly by his own people, by some fanatical redneck or some fanatical rightwing Cuban who might spot him and Luna holding hands on the sidewalk.

I glance at Luna’s uncle up on the porch, a man who has spent his life at political rallies. He is no longer dozing. Perhaps he is working on his next diatribe. But he speaks no English and wouldn’t care what we are saying, they tell me. Still he knows that in the front yard of his sister’s house, the place where he sleeps each night. there are three maricons, three faggots, chattering away, and one of them, Luna, takes another, Gilberto, to bed three, four nights a week under the roof where he sleeps. And sometimes, [he morning after such a night, Luna will silently drive his uncle to the radio station where he spreads his bitter oratory.

If these worrisome complexities are just the forces that have driven many middle class Anglo gays to move away from their homes and into safer enclaves like the Castro or West Hollywood or Greenwich Village, it is the fact of cultural contradiction which seems to have drawn Luna back. At 30, he has lived in gay ghettos in San Francisco and New York. Coming back to Miami has been explicitly about comprehending family and reinforcing his Latino identity. To explain what he means he turns the conversation to sex and language.

“Having sex in Spanish makes a big difference to me-all the communication that goes with sex. We flip back and forth between different languages.

“If You catch me when I am just waking up, I would more likely respond in Spanish than in English, even though I have been in this country longer.”

He stops, to think.

“When I count I switch to Spanish.” Counting, he reminds me, is among the earliest and most intimate associations we have with language, one of the first techniques humans use to order their world, one of the last things we learn to do comfortably in a new language. Only recently has he come to feel the cultural resonance as a Cuban that the language stirs in him. “I always thought that it wouldn’t make a difference, but later on I came to realize that it would, that ‘these [Cubans] are my people.’ Why would someone stick with their people?” he asks himself rhetorically, but he has no perfect answer. Instead he is more intent on exploring the question. ‘The most satisfying sexual relationships I have had have been with other Cubans. Even though I don’t really look Cuban the way I dress or the music I listen to. People call me a punk, and it always has put me outside of being Cuban.

“Like with him… ” He gives a giggle grin at Gilberto, who breaks in: “We just took a little vacation, in central Florida, and it was really good to be able to speak in Spanish and be really sexy with each other… to say really hot things to each other in front of a lot of people who didn’t know.”

Luna breaks in. “No matter how passionate I may be feeling in English it just doesn’t go across as much as it does in Spanish. When I talk in Spanish, I think in English. But I think that I feel it in Spanish, and think it in English, and then I translate it.”

Something more powerful than their own personal relationship as individual gay men seems to propel them toward their mutual search for family. Throughout his twenties Luna lived in a succession of communes, which included both straights and gays. -Anglos and Latinos. he says that the sense of personal fulfillment he wants drives him to some sort of larger living arrangement which reflects both his personal identity and his place in society. Gilberto, much younger and not yet traveled in the world, ,,cents clear that he in no way wants to lose the communal and community ties which his extended family and all their traditional celebrations have provided him.

Even when they speak of leaving Miami, Gilberto insists it wouldn’t be the same as it is when all those gay Anglos leave home. “I know I’d have to come here for Christmas and New Years,” he in a tone of absolute certainty. “I know I’d have to come here for Mother’s Day, and I’d have to make a big effort [to be here] for my birthday.”

No one will know whether they can maintain such promises to themselves until they are each firmly implanted in the careers, geography and ambitious of middle age. For two hundred year-, first generation Americans have made such promises repeatedly, and few have managed to keep them. What may differ for Luna and Gilberto is the enormity of the Hispanic presence in America, and the steady replenishment of linguistic and Cultural tradition provided by the proximity of the Caribbean and Mexico. For anyone who has spent more than a weekend in the cities of South Florida and the Southwest knows instantly how completely the bonds of language and family networks have overcome the barriers of borders. Too often Anglo Americans’ incapacity to use other languages leads them to miss the profound Cultural insurance locked within language. When Luna and Gilberto confess that sex is altogether different when they make love in Spanish, they are referring to more than sexual talk. When they visit family theme parks in central Florida and flirt with each other in street Spanish that is incomprehensible to the Anglos, they are being more than petulant.

Like children who invent their own secret languages, like immigrant parents who withhold the mother tongue from their children in order to preserve the private memory of their own pasts, Luna and Gilberto are repeating in ancient ritual which at once unites their own sense of personhood and does so by declaring their connection to a cultural identity grander than themselves. Even further, the dual secretiveness of street language and the double entendres in their “camp” talk intensify their sense of being “gay spies” in a straight land. All these layers of language and interpretation, of straight speech, gay speech, Spanish speech and raunchy invisible sex speech become a framework through which they express irrepressible drive,,, to hold on to family and culture.

©1993 Frank Browning

Frank Browning, a freelance writer in San Francisco, has just completed a book, “The Culture of Desire: Paradox and Perversity in Gay Lives Today,” published by Crown.