How intrusive searches and disposal problems are hampering talks toward an historic ban on possessing war poisons.

At the sound of approaching aircraft, Farouk Abdullah, an elder in the northern Iraqi village of Ekmala, squinted up at the brightening summer sky. It was an unusual sound for this Kurdish hamlet. Five warplanes swept into view and dropped a series of bombs. Rather than exploding loudly, the bombs produced a muffled burst and billows of yellow clouds. The smell was reminiscent of onions or garlic. As cries of alarm rose from the mountain community, Abdullah ran. “Many people fell down, but I could not see clearly,” he recalled. “I tried to run away from the smoke, but then the wind changed. I tried to run back, but I fell and began to vomit.”

As Abdullah recovered over the next few days, he watched his world change. “The leaves fell off the trees,” He told a U.S. Senate investigative team. “The fish in the brook died. Anyone who touched the clothes of the dead people became blind.”

Elsewhere in the village on that early morning, August 25, 1988, Ramazan Ali saw six planes disgorge the yellow clouds of war. “Animals fell down and died,” he said. “We ran to the mountains.” Fatally injured in the attack was Ali’s two-year old son, Emin. “He turned black and blue,” Ali recalled.

Eauk Abubeki estimated he was about a kilometer from the attack. “When they dropped the bomb, a yellow cloud was formed and a smell like rotten garlic came out. I dipped my shawl in the water and wrapped myself in it. I buried 33 people.”

In the Kurdish town of Dihok, Ekrem Mai, a 27 year-old member of the Pesh Merga resistance movement, compared the smell to rotten parsley. “There were no wounds,” he said. “People would breathe the smoke, then fall down and blood would come from their mouths.”

The gas attacks on Iraqi Kurds by the forces of Saddam Hussein were a modern reminder of the indiscriminate and unnecessarily cruel quality of chemical warfare. While the evidence of chemical attack is largely anecdotal, critics say the Iraqi leader counted correctly on the debilitating and deadly effects of poison gas to cripple the Kurdish resistance. Investigators believe the blistering assaults claimed thousands of lives.

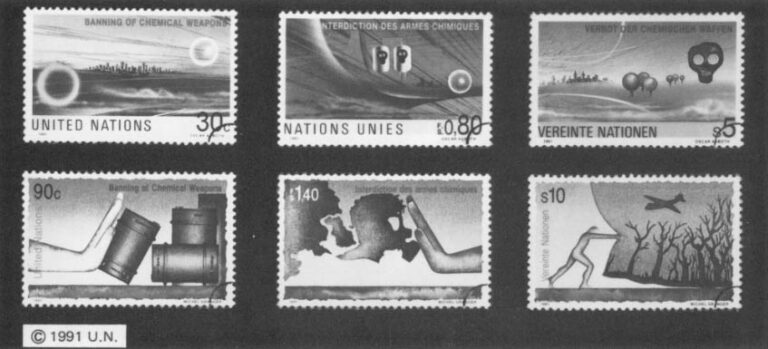

First used on a large scale in World War I, chemical weapons stirred such widespread revulsion that their use was banned under the Geneva Protocol of 1925. But the treaty, agreed to by 130 nations, including Iraq, has no real teeth. It has allowed the manufacture and possession of chemical weapons, and contains no provisions for punishing countries that resort to their use.

As the world adjusts to the post-Cold War power shifts caused by the dissolution of the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact, chemical weapons stand as one of the most obvious threats to peace.

Part of the problem is that the production of these deadly poisons is astonishingly simple. War poisons can be made fairly easily from other chemicals that have legitimate uses in the manufacture of pesticides, plastics, paper, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, detergents, dyes, ceramics and other common materials. “The same chemicals used in laundry detergents are two processing steps away from a deadly gas,” says Will D. Carpenter, vice president of Monsanto Agricultural Chemicals.

Spurred to some degree by chemical combat in the Iran-Iraq war, diplomatic progress toward a comprehensive chemical weapons ban has been relatively swift since the mid-1980s. Negotiators now predict they are only months away from completing a treaty to prohibit the manufacture and possession of noxious or asphyxiating compounds that have military applications. Ambassador Stephen J. Ledogar, chief U.S. negotiator at the chemical weapons talks in Geneva, told Arms Control Today: “This is not part of my instructions, but my own personal suspicion is that you can count back from the end of the first Bush administration and subtract the time you need for ratification of a CW (chemical weapons) treaty, and you can come pretty close to the kind of timetable that senior policymakers are thinking about.”

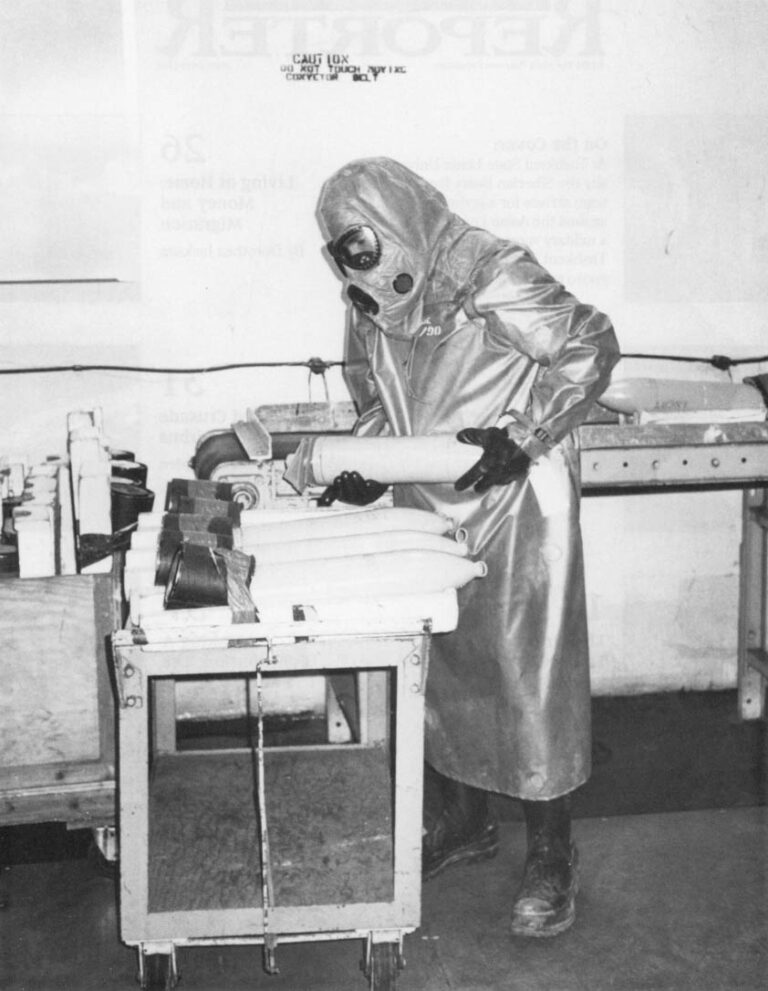

The owners of the largest chemical arsenals, the United States and Soviet Union, are working out the details of a bilateral treaty signed on June 1, 1990. Despite the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the weakening of the central government, U.S. officials say they fully expect Moscow to meet its treaty obligations. The agreement calls for a ban on production and the reduction of each stockpile to 5,000 metric tons of chemical agent by the year 2002. That’s one-fifth of what the United States has now, nearly all of it in older so-called “unitary” munitions stored at eight locations in the continental United States and on Johnston Island, southwest of Hawaii. A multinational agreement would supersede the U.S.-Soviet pact, requiring complete destruction within 10 years. But while the United States already has begun to destroy the first of its older weapons, at an Army incinerator on Johnston Island, the Soviets have no destruction program in place.

Environmental concerns over proposed methods of destruction remain a major barrier to any chemical weapons ban.

Equally worrisome may be the huge and pervasive system of inspections required to make sure that countries are complying with the multilateral ban. Under the current draft, participating nations may demand inspections of another country’s facilities “anywhere, anytime” with no right of refusal. In the United States, this means teams of inspectors nosing around government labs and private businesses on an unprecedented scale, perhaps without benefit of search warrants. That has raised constitutional qualms as well as concern about risks to national security that are unrelated to the chemical industry. Will Japan be allowed, under a chemical weapons treaty, to inspect electronics labs in Silicon Valley? Will the feds join foreign agents in nosing through the paint cans in your garage?

The courts have refused to rule explicitly whether inspections arising from foreign affairs must comply with the 4th Amendment, which protects against unreasonable searches and Seizures. “If they were to be abused, challenge inspections could become open-ended fishing expeditions, reaching both businesses and homes,” said Edward Tanzman, an attorney for the Energy and Environmental Program at the Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois. If, in Tanzman’s view, the chemical manufacturing industry qualifies as a “pervasively regulated industry,” warrants may not be needed.

“There is a line of Supreme Court decisions that says there is an imputed social contract between pervasively regulated industries-the classic cases being the liquor industry and the firearms industry-and the government, in which these industries implicitly consent to warrantless searches in return for being allowed to do business at all,” Tanzman says. However, a 1986 high court ruling involving Dow Chemical Co. cast doubt on that interpretation, he adds.

And what about facilities that don’t belong to the chemical industry? The answer may be for Congress to pass laws that prevent or at least discourage citizens from asking for injunctions against searches they know are coming. At the same time, the legislation could offer them hefty compensation for any misuse of information acquired through a treaty compliance inspection. And any evidence of unrelated violations-of environmental laws, for instance-found during challenge inspections would have to be held inadmissible in criminal proceedings, Tanzman argues.

In an article with Barry Kellman in the New York University Journal of International Law and Politics, Tanzman notes that the U.S. Supreme Court has already ruled that warrants aren’t needed for health and safety inspections of mining operations. In passing the Mine Safety and Health Act, Congress noted “the notorious ease with which many safety or health hazards may be concealed if advance warning of inspection is obtained.” Presumably, Congress could lay a similar foundation for enforcing an arms-control treaty.

But the treaty drafts are continually changing-negotiators call this a “rolling text”-and it’s difficult to guess the final language. Compounding the difficulty, the United States has flip-flopped on a number of issues in recent years. “Challenge inspections” were first proposed in the draft treaty presented in Geneva in 1984 by Vice President Bush. The idea was met with almost universal booing. The British, for instance, were “highly skeptical,” recalls Matthew Meselson, a Harvard biochemistry professor who has been involved with chemical-weapons issues for many years. “Since that time, however, they have carried out a series of six trial challenge inspections of their own sensitive facilities,” he says.

Using various means of “managed access,” such as shrouding consoles and equipment, the British found that inspections can be effective in verifying compliance with a treaty without compromising legitimate secrets. The result: the British now are in favor of the concept. So are the Soviets. The United States, meanwhile, has backed away from its original plan and now favors limiting challenge inspections to facilities on a specific list. The administration remains steadfast on that point despite at least three apparently successful trial inspections at U.S. facilities.

Two changes in policy by the Bush administration have been hailed as breakthroughs for the convention. The United States and Soviet Union in 1990 proposed, as a way of promoting “universality” or the widest acceptance of the treaty, that nations with chemical stockpiles be allowed to delay the destruction of the last two percent of their stockpiles until all countries capable of producing chemical weapons had become parties to the agreement. The so-called “two-percent option” was roundly criticized and President Bush finally dropped it last May on the eve of the opening of this year’s round of talks in Geneva.

At the same time, Bush announced that the United States would “forswear” the use of chemical weapons, even in retaliation to a chemical attack, once the multinational treaty enters into force. The right of “retaliation in kind” had been reserved under the 1925 Geneva Protocol and had been a mainstay of U.S. policy aimed at deterring such attacks.

The dramatic policy switch shows Just how bad Bush wants chemical weapons banned on his watch. “It has moved the process forward at least that far,” remarks U.S. Rep. Martin Lancaster, DN.C., a Congressional observer at the Geneva talks. “But it has heightened the differences that remain.” These include inspection issues, who will pay for verification and the question of providing protection to states that are attacked or threatened with chemical weapons.

On the bright side, one study indicates the cost to the United States of implementing the treaty will be relatively cheap. The Alexandria, Virginia-based Institute for Defense Analysis, under a Pentagon contract, estimated that inspection-related activities will cost the international organization created by the convention $800 million over 15 years. The United States would be responsible for about $400 million of that, the study said. The costs of challenge inspections were not included, since the exact procedures have yet to be determined.

Apart from the treaty negotiations, 20 industrialized nations, members of what’s called the Australia Group, have agreed to control exports of 50 common chemicals that can be used to make munitions.

The U.S. Commerce Department now requires-and will generally deny-licenses for the export of these 50 “dual-use” chemicals to Iran, Iraq, Syria and Libya, and requires a license for the export of nine of the chemicals to any country outside the Australia Group. Under an agreement by the 20 nations last May, licenses will be required by the end of 1991 for exports of any of the 50 chemicals to countries outside the group.

This alone is not expected to stop chemical weapons proliferation. In its 1991 foreign policy report to Congress, the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Export Administration said nearly all 50 controlled chemicals can be obtained from other foreign countries. Mentioned were India, China, the Soviet Union, Brazil, Mexico, Poland and Israel. “Export controls can be helpful in slowing down the program of developing nations that want to have chemical weapons,” says Harvard’s Meselson. “But export controls are a temporary palliative. They cannot prevent nations from producing chemical weapons if they wish to have them. One needs to recall that 70 years ago Germany was able to produce vast amounts of mustard, still today regarded as an effective chemical warfare agent. The process they used required only ethyl alcohol, sodium sulfide and bleach.”

While supportive of the negotiation in Geneva, the U.S. chemical industry considers export controls a poor substitute for a treaty. “When we speak of CW technology, we are not discussing the cutting edge of chemical science,” says Monsanto’s Carpenter, a spokesman for the Chemical Manufacturers Association, the industry’s principal trade association. “Trying to halt the spread of 50-year-old techniques is no more practical than trying to ‘un’-invent fire.” Barring exports of chemical manufacturing equipment also hampers efforts to bring developing nations up to the same health and safety standards as the industrialized West, he says.

Matthew Meselson, a Harvard University biochemistry professor, has been involved with chemical-weapons issues for years.

The wild cards in the deck, of course are the Middle Eastern countries suspected to have chemical arsenals. Will Libya and Syria sign the Geneva agreement? Will they insist that Israel destroy its nuclear weapons as part of the deal? “The interesting question now is whether the neutral and non-aligned participants will climb aboard and make this happen or jump overboard and torpedo it,” says Brad Roberts, editor of The Washington Quarterly and a fellow in international security studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “I think the Gulf War will really dampen the proliferation trend. As states in the developing world tote up the benefits and disadvantages of being under the disarmament regime, I think most of them will come to find that it’s in their interests to be inside the regime.” Still, holdouts among Arab nations would jeopardize ratification of the treaty by the Senate, Roberts predicts.

Equally serious is the question of safe disposal of chemical weapons stockpiles. The U.S. plan calls for the construction of incinerators, modeled after the plant on Johnston Island, at each of eight storage sites in the continental United States. That already has brought legal challenges and community protests in Hawaii, Kentucky and Maryland.

In the Soviet Union, a pilot disposal plant near Chapayevsk on the Volga River has been kept idle because of environmental concerns about a chemical encore to Chernobyl. “The Soviet public is so deeply skeptical of its government generally, but especially on environmental issues-especially on military environmental issues-that their ability to come up with a demilitarization program and destruction plant that will satisfy mobilized groups to the point where they will let it happen is doubtful,” Roberts said in an interview.

Most observers fear that the Soviets certainly will be unable to begin destruction of its 50,000 ton stockpile by the end of 1992, the deadline set in the bilateral agreement. Says Geneva negotiator Ledogar: “Until we are confident that the dates that are in that agreement are going to be met, I cannot conceive of this administration, even if we finish the protocol, putting the package before the Congress and risking, while it’s being looked at up there, categorical revelations that the Soviets cannot meet the destruction dates.”

©1992 James Borg

James Borg, a science writer based in Honolulu, is investigating the future of chemical weapons.