Richmond, KY-Across gently rolling grassland just east of Clark-Moores Middle School, the Lexington-Blue Grass Army Depot sprawls in sad tribute to a national security agenda that is no longer relevant.

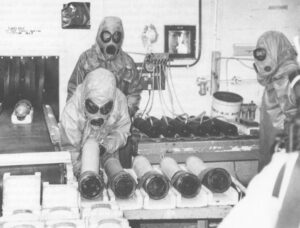

Since the early days of the Cold War, the 15,000-acre installation has sheltered thousands of rockets and artillery rounds containing chemicals designed to disrupt breathing and other bodily functions, often with deadly results. These so-called nerve agents-liquids with the arcane designations GB and VX – have never been used in combat. The third type of agent stored here, mustard, meant to sideline soldiers by blistering their lungs and skin, hasn’t seen wide service since World War I. Yet tens of thousands of tons of those compounds were manufactured and stored against the possibility of war with the former Soviet Union. Now decades-old and obsolete, these relics of East-West confrontation put the Pentagon in a bind.

Comprising some 25,000 metric tons of deadly or highly toxic liquid, the U.S. chemical stockpile is slowly deteriorating. The biggest headache is the unserviceable M-55 rocket, stored at Lexington-Blue Grass and five other sites: The M-55 contains a propellant that eventually will become Unstable and could ignite spontaneously. Some of the nine storage sites, notably Johnston Island in the Pacific, are far from populated areas.

But others, including Lexington Blue Grass, stand tooth by jowl with towns, schools, farms and ranches. Congress in 1985 ordered the Army to destroy these stores.

But in the incongruous drama of modern environment politics, many people who live near these weapons don’t want them destroyed. At least not right where they are. At least not right away.

“It looks to me like we can ship it out and destroy it someplace else,” remarks Douglas Roberts, principal of Clark-Moores, where 850 children go to school.

The focus of the debate is the Army’s decision, after years of study, to incinerate the chemicals and casings in a specially-designed, automated plant at each of the nine sites. While the Army has asked a committee of the National Research Council to take one last look at alternatives to incineration, the first plant has already fired up at Johnston Island. A second incinerator is well under construction at Tooele Army Depot in Utah.

According to its increasingly vocal detractors, incineration is unsafe and environmentally hazardous. Furnace smoke stacks emit all sorts of unsavory or unknown by-products, these critics charge. “It’s an open-ended technology which emits toxic and hazardous substances into the atmosphere,” says Craig Williams of Berea, Kentucky, a member of environmental group Common Ground. “You are transferring your problems from a landfill reality to a landfill-in-the-sky reality.”

Federal agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency and the Public Health Service, insist that incineration is safe, that the required system of air monitors and filters Will prevent unhealthy concentrations of chemical by products from entering the atmosphere.

But there’s another dimension to the protests. While Congress has ordered that all nine chemical-weapons incinerators be dismantled once the weapons are gone, residents say they fear that just won’t happen, that these plants will become a permanent part of their community’s landscape.

“We’re hoping to stop the incinerator cold,” says Linda Koplovitz, a founding member of Concerned Citizens for Maryland’s Environment, Inc., who lives near the Army’s Aberdeen Proving Ground. “Once the government spends $350 million on our incinerator, they are not going to want to tear it down. They are going to look at it and say, ‘Hmmm, how call we change this, how call we modify it?’ and we are going to become an East Coast hazardous waste facility.”

Kathy Flood, whose family once owned 350 to 400 acres that are now part of the Lexington depot, expresses similar skepticism. “You know, they’re closing 400 bases,” she says. ‘They’re all heavily contaminated and they’re not going to be able to turn those bases back until they’ve been cleaned up, and it sure Would be handy to have eight incinerators scattered around the countryside to take care of some of these problems.”

In short, the Army’s proposed solution is viewed by many as a more immediate threat than the original problem it sell. But each alternative has drawbacks, its own set of costs ill money, time and possibly safety. All this has turned the chemical weapons disposal program into the ultimate game of political hot-potato.

“The level of anxiety in a few of the communities surrounding the eight sites has at times been high,” Dr. Sanford Leffingwell, a medical epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control, told members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science at their annual meeting in Chicago. “Children and adults alike fear for their life and health. We don’t know the prevalence or the severity of the problem, but we have seen its effects at public meetings.”

In April 1991, an estimated 1,000 residents of Kentucky’s Madison County, which includes Richmond and nearby Berea, packed it school auditorium to protest the Army’s plans. Many elected officials sympathize.

“I want to make it very clear that I do not want the weapons burned on-site and will continue my efforts to see if this can be avoided,” said U.S. Sen. Wendell Ford, a Kentucky Democrat. The congressional Office of Technology Assessment, at Ford’s request, conducted a study of the disposal program. The agency recently concluded that “major political and social obstacles” stand in the way and that the Army has “no backup plan” beyond incineration.

Kentucky probably has the best argument for transporting the weapons to another location for disposal. The depot in Richmond accounts for only 1.6 percent of the total U.S. stockpile, the smallest amount in any one place. Why should Richmond warrant the same $300-million incinerator as, say, Tooele, Utah, home to 42 percent of the stockpile?

In neighboring Indiana, Gov. Evan H. Bayh wants his state’s stores, of VX agent, housed in ton containers at Newport Army Ammunition Plant, moved away as well.

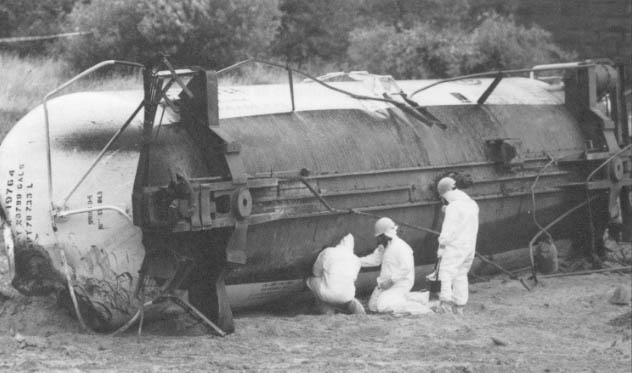

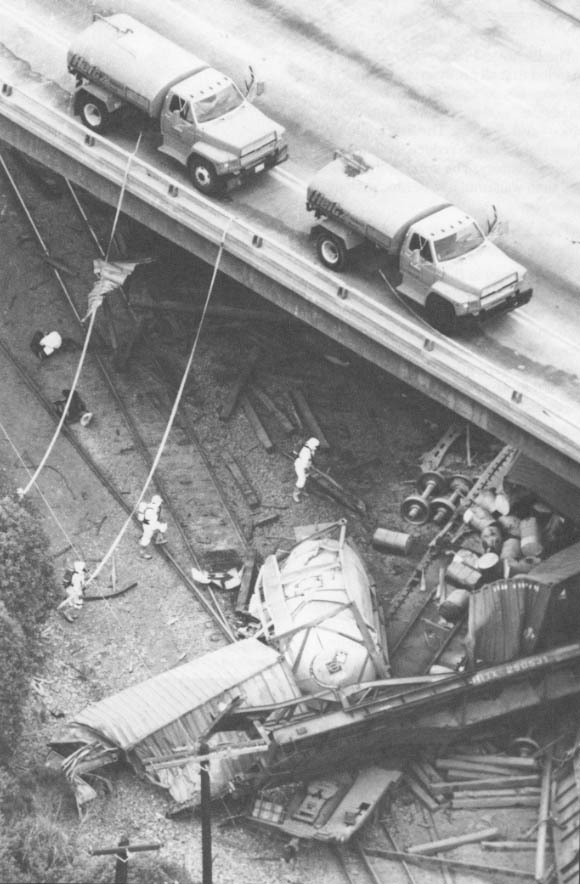

The Pentagon responds that moving, my of this stuff, regardless of how it’s configured, is unnecessarily risky and politically unfeasible. Transporting the Kentucky stockpile alone would require either 1,500 aircraft flights or four, 50-car trains. An air or rail accident along: the way would create a huge poisonous cloud, “a major catastrophe” in the words of Brig. Gen. Walter Busbee, the manager of the Army’s chemical demilitarization program – Adjacent states have said they don’t want my toxins traversing their turf.

However, the Army’s recent transportation record appears good. In the fall of 1990, in an elaborate and tightly controlled mission called Operation Steel box, more than 100,000 nerve-gas artillery rounds were moved by truck, train and ship from a U.S. Army post in West Germany to Johnston Island. In fact, the environmental assessment prepared by the Army for the Steel Box shipments sought to downplay the risks of transportation. From 1946 to 1986, chemical weapons were moved routinely by road. rail, sea and air with “only 43 major accidents/incidents,” none fatal, the report said. Of those, 31 occurred before 1950 and involved the transportation of World War II mustard weapons made by Germany. No figure was given on the volume of chemicals transported. By chemical weight, the shells from Germany accounted for 1.5 percent of the U.S. stockpile, about the same, share as in Kentucky.

But while residents and representatives of Kentucky and Indiana may be anxious to run their stockpiles out (of town on a rail, the potential recipients are not as enthusiastic about the idea. Members of the 15-nation South Pacific Forum, meeting in Fiji, issued strong objections to the shipment of the U.S. chemical munitions from Germany. Never mind that tiny Johnston, 825 miles downwind from Hawaii and 1,400 miles east of the Marshall Islands, is one of the most remote sites on the planet. Some Pacific island leaders openly worried that Johnston would become the destination for all U.S. chemical weapons – and possibly those of Russia as well. President Bush, at an unprecedented meeting in October 1990 with leaders or representatives from eleven island nations, pledged that the incinerator would not become a fixture on the Pacific horizon. “We confirmed that these munitions will be destroyed safely, on a prioritized schedule, and that once the destruction is completed, we have no plans to use Johnston Atoll for any other chemical munitions purpose or as a hazardous waste disposal site,” Bush told reporters after the meeting in Honolulu. The sole exception would be chemical ordnance from World War II found on Pacific islands.

U.S. Sen. Daniel Inouye, who had expressed support for the Johnston I-land incinerator after a tour of the facility in August 1990, has come down firmly against was any extended use. As chairman of the Defense Appropriations subcommittee, Inouye helped push through legislation that prevents expenditures for further transportation of chemical weapons. U.S. Sen. Daniel Akaka, a sponsor of the bill, said it would “help ensure that the Pacific does not become the world’s chemical dumping ground.” Unless superseded by future legislation, the 1991 measure serve, to freeze the U.S. chemical stockpile at its current locations.

Congress can always change its mind – and has.

Initially, the stockpile destruction effort was to have been limited to M-55 rockets, but Congress expanded it to include 90 percent of the other obsolete single-agent or “unitary” munitions. Congress also passed a law requiring that the chemical weapons incinerators be dismantled once the stockpile was destroyed. In a subsequent switch, it directed the Army to study possible future uses for the plants.

The study, completed last year by the MITRE Corporation, said that the Lexington-Blue Grass facility could be used to destroy conventional munitions and for the thermal decontamination of soil, sludges and contaminated carbon filters. But the study noted “significant local opposition” to the incinerators. That, taken with some economic disadvantages, recommends against any further use of the Kentucky furnace, MITRE said.

By contrast, in gung-ho Pine Bluff, Arkansas, the public generally favors keeping the incinerator active for the disposal of other military and civilian hazardous wastes, according to the MITRE study. But from an economic standpoint, the study found Pine Bluff desirable only for the continued destruction of smoke bombs, tear-gas canisters, contaminated containers and old munitions found at firing range,,. The facilities planned for Tooele, Utah, also carried some advantages for Continued operation.

Talk like that worries the opponents of incineration.

“We have a very unique environment out there that is now going to become questionable,” says Cindy King, a member of the Sierra Club in Utah.

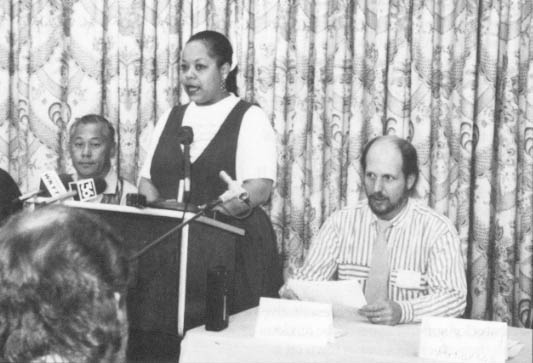

Thus, in November 1991, at the Richmond Holiday Inn just off Interstate 75, representatives from opposition groups in nine states met for the first time to formulate unified strategy. Sponsored by the Kentucky Environmental Foundation and Common Ground, and co-sponsored by Greenpeace and the National Toxics Campaign Fund, the meeting was billed as the International Chemical Weapons Disposal Citizens Summit.

The term “international” attested to the presence of Sergey Rudolfovich Fomichov, a member of tile movement that successfully fought the opening of the Soviets’ chemical weapons disposal plant at Chapayevsk. An environmentalist and magazine editor in Dzerzhinsk, near Chapayevsk in the Volga River basin, Fomichov recounted how the April 1986 Chernobyl disaster provided the impetus for active environmentalism in the former Soviet Union. For the Chapayevsk protests, citizens hunkered down in a Resurrection City-style encampment on the plant’s periphery. “Tens of thousands of people took part in the actions,” said Fomichov.

At the Richmond summit, the single most difficult issue was whether some chemical stockpiles should be moved, an option strongly favored by the Indiana and Kentucky delegations. But moved where? Any shipment – would automatically become some other state’s problem. Others favored a ban on transporting the Weapons. After long discussions behind closed doors, the delegates settled oil a compromise: stockpiles should not be moved if they are merely going to be destroyed elsewhere by incineration, an “inappropriate technology.”

The Richmond conferees recommended that all future arms control agreements distinguish between “demilitarization” – that is, dismantling weapons – and disposal.The first could be done right away to reduce the battle ready inventory. The second, they said, can then wait until a better technology emerges.

Thus arose the ironic consensus that time is not the enemy, but a friend.

“Technology in the field of waste management is changing as rapidly if not more rapidly than almost any other type of technology on the planet today,” said Ross Vincent of the Sierra Club in Colorado. “If it were private industry that needed these new methods, they would be available in six months to two years.”

Added Kathy Flood of Kentucky, “I feel very strongly that the stockpile is safe enough to be maintained for mother technology or transportation, either one. These are field weapons. They are designed to be thrown in the back of a jeep and battled around and then hauled out and launched. They were designed for rough use.”

The Army’s practice of packing leaking munitions in airtight cases can be continued for decades without safety threats, Flood and officers argue. “Delaying this process does not mean increased, prolonged danger to the community,” said Pete Conroy, president of the Alabama Conservancy. The Anniston Army Depot in Alabama is the next in line for the construction of an incinerator. so Conroy and colleague Jeanette Crow confess to a sense of “desperation,” particularly since the Anniston community solidly supports the Army. “They have been good environmental stewards,” he says. They put bluebird boxes up all over their base, and they recycle and they do everything else extremely well. I can’t say they have been a pinnacle of information distribution oil this particular issue.”

At the AAAS meeting in Chicago, Leffingwell, the medical epidemiologist assigned to the chemical weapons disposal program, agreed that lack of information has contributed to fear in some communities. “The truth of the matter as we see it is, first, I here is a small but present risk of catastrophic release from storage,” he said. “Such a release could under proper weather conditions or under sufficient magnitude of release. endanger people beyond the installation boundaries. Adding a demilitarization plant increases that risk only slightly.”

A private consultant now is preparing an emergency plan for Clark-Moores school. Say,, Roberts, the principal, “They are going to show us what we need to do to isolate ourselves within the building, or – if possible – evacuate, which, you know, we’re so close, unless the wind was blowing the other direction, there wouldn’t be a chance to evacuate anyhow.

Until these weapons are destroyed, their most likely victims are not their once-intended targets – the Soviets, but thousands of Americans in communities like Richmond.

©1992 James Borg

James Borg is a freelance writer in Honolulu specializing in chemical weapons.