Photo by James Rupert

TASHKENT, U.S.S.R.-On the night last August that masses of Muscovites undid the Bolshevik Revolution, most people here in the Soviet Union’s fourth largest city appeared not to care.

On the flickering television image from Moscow, 1700 miles away, a sea of Russians pressed close to their parliament building, roaring of their victory over the bureaucrats and military officers who had tried to renew the Communist Party dictatorship with an attempted coup. But, at Tashkent’s dreary Sayokhat Hotel, the only witnesses to this history were a group of vacationing Ukrainian office workers. The hotel’s Uzbek employees tended laconically to business, little interested in what the Russians were up to in Moscow. In the restaurant, the usual evening crowd of young Uzbek and Tatar men drank vodka and danced, arms outstretched, to Middle Eastern tunes.

The drama of the Soviet Union’s stunning collapse, heightened worldwide by the live coverage of the raw power struggle in city streets, has helped obscure an essential fact: last summer’s Soviet political revolution was a European event. Among most of the 50 million people living in the steppes, mountains and deserts of Soviet Central Asia, the changes in Soviet Europe were neither celebrated nor fully accomplished.

In the months since the August coup attempt, Western governments and media have focused mostly on the struggles of Western Soviet republics as they attempt independent nationhood. The five Islamic republics of Central Asia, and stretching from the Caspian Sea to Mongolia, have gotten less attention.

Yet it is Central Asia–known often among its mainly Turkic peoples by its historical name, Turkestan–that faces the more basic struggle. While the sudden collapse of the Soviet Union left the European republics to pursue a difficult path to independence and membership in the European family, it left the Central Asians with no clear path at all. While they have begun to follow Soviet Europe in rebelling against communist rule, they have nothing to replace it with. And, as the Soviet Union’s poorest region, facing one of the world’s most dangerous environmental crises, Central Asia will need a stable political system merely to avoid a descent into political extremism and violence.

This region’s uncertain future carries high stakes, not only for itself, but for the stability of the continent surrounding it. Central Asia embodies the combination of deep internal divisions and competing neighbors that have proved disastrous in recent years to countries such as Lebanon, Cambodia and Afghanistan. As Central Asia emerges from a century behind the walls of Russian empire, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan compete to win it to their own brands of Islam. Turkey and Iran seek to reassert their old cultural links. India and Pakistan, in their continuous rivalry, each hope to win influence in Central Asia and isolate the other. Afghanistan, still writhing in civil war, is a ready bazaar of militant Islamic fundamentalists, ethnic nationalists–and guns. And all of these neighbors, plus orthodox Communist China and a democratizing Russia, hope to export their own political models.

Outside political forces seeking clients in Central Asia are likely to find them. In each republic, there are regions, tribes or clans that feel they have lost out in continuous struggles against their rivals for power and wealth. Under the apparently seamless pavement of Soviet socialist republics and communist parties, such struggles continued unabated during the Soviet period, and the losers may readily welcome allies from abroad. Outside intervention may be easier from where–as in Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and China–there are populations of the same ethnic or linguistic groups as those of Central Asia.

A CULTURAL DIVIDE

Tashkent is Soviet Turkestan’s metropolis, a city of 2 million people that rules the region’s most populous republic, Uzbekistan. It is a curious mix of Asia and Europe, superpower and Third World, that symbolizes many of Central Asia’s divisions.

This city’s decaying, cubic apartment blocs and heroic communist monuments sprawl at the edge of Central Asian grasslands that once formed the heart of Genghis Khan’s Mongol empire. During the summer and fall, a dusty haze obscures the Tian Shan mountains, which rise to the east to form forbidding borders with China and Afghanistan.

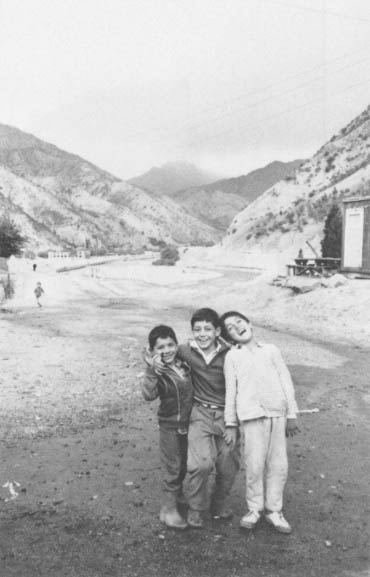

Tashkent often wears the face of modernity and prosperity. Its marble-walled subway system whisks factory workers, bureaucrats and students–many well-educated and well-dressed–to work and home. But work is usually inefficient industry or bureaucracy, and homes are crowded, dingy apartments that represent generations of broken Soviet promises for better lives. And much of Tashkent offers the sights and smells of a Third World city over-burdened by its population. In many neighborhoods, city workers sweep the trash into piles at the curb and burn it, filling the air with the pungent odor of Bombay or Karachi. In the old city, a warren of alleys among mud-walled houses, children swim in canal waters that carry, if faintly, the odor and gray tinge of human waste.

Central Asia’s clash of cultural and political visions is obvious here. In a downtown bazaar, young Uzbek men and women crowd into a shop to buy pirated cassettes of Madonna, Michael Jackson and other Western artists. “Rock and roll is about doing the things that you want, instead of what people tell you to,” said Timur Saidov, a customer. Firuza Makhmudova, a 22 year-old student of English, said she prefers to dance to the mandolins and tambourines of traditional Uzbek music, but spends hours at home trying to make out the meaning of American country tunes such as Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee.”

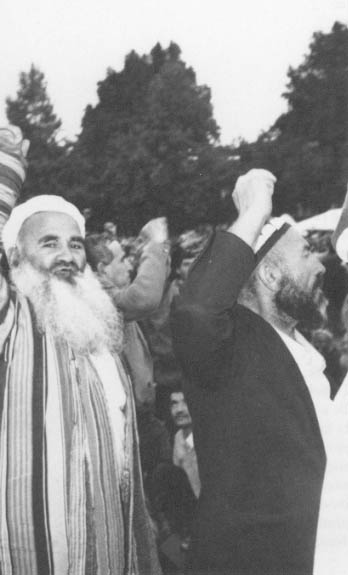

Outside the Tillya Sheikh mosque in Tashkent’s old city, the imported ideas are from another tradition. At a Friday noon prayer, Mukhammad Rasulov, an wizened Uzbek, drew a crowd of men, young and old, with his religious pamphlets and books, some from Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, spread on a blanket on the stony ground. A 20-page pamphlet teaching the rudiments of the Arabic alphabet and showing, in simple sketches, the proper way to prostrate oneself for Islamic prayer, sold for six rubles–a higher price than for almost any book in the largest downtown bookstore.

AN INCOMPLETE REVOLUTION

During the August battle in Moscow between orthodox communism and pluralist democracy, Tashkent remained silent, its people reluctant even to openly acknowledge the struggle. On the morning of August 19, hours after Moscow radio began broadcasting the declaration of Communist power by the coup committee, people bustled normally past the Maxim Gorky metro station. The few snatches of conversation from passersby dealt with life at home or at work. I wondered whether perhaps news of the coup had somehow not reached the streets, until a woman approached a group on the sidewalk. “Excuse me–has anyone heard if the airport is running?” she asked. “No news,” said one man, as others shrugged. The acknowledgment of the Communist coup lasted only for that moment, switched off abruptly as people again turned their eyes from each other and stood silently, with masked faces.

Unlike Soviet Europe, where nationalist and mostly pro-democratic governments banned the Communist Party following the coup, the conservative communist governments in four of Central Asia’s five republics simply changed their parties’ names and held tightly to power.

During the coup, “we could see a difference between Soviet Europeans and Soviet Asians,” said an Anwar Usmanov, a dissident journalist in Tashkent who was arrested by Uzbek police during the coup for having held a meeting with other government opponents. “In Moscow and Leningrad, people had lost their fear of dictatorship, and they stood up to demand their rights. Here in Asia, there are only a few people who have lost their fears… The Europeans have some historical experience with democracy,” he said, “but our only governments have been dictatorships,” Usmanov said. Before Soviet and czarist rule, Central Asia was ruled by despotic Islamic emirates, sometimes under the control of Mongol or Persian empires.

But the loss of fear has begun, in part because of the Soviet European example. In Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, thousands of Tajiks rebelled against the communists in September, striking and demonstrating for the government to resign and call elections. Watching a rally at the Supreme Soviet building, a Dushanbe mullah, Abdulghaffar Khodoidodov, said: “We chose this method [of opposition] after seeing on television how it worked in Moscow and the Baltics. We saw that it could be done peacefully.”

NO PATH TO FOLLOW

Wile Central Asians are beginning to follow Soviet Europe in forcing communists out of power, the greater challenge is what to replace it with. The East-West cultural divide here prevents consensus on how to organize society and government. In September, the Tajik opposition movement managed unprecedented cooperation between Westernized intellectuals who take Europe as their political model and Islamic leaders who cited Iran and Saudi Arabia as examples of what they consider an Islamic democracy. Even though “these people can unite to oppose the communists …. they don’t have even remotely the same idea of how to conduct politics in the future,” said a European-educated Tajik in Dushanbe. It has been unclear how long such groups will continue to cooperate.

As in other traditional societies, in Central Asia, the battle of ideas remain largely the apparent politics. These–evident in newspaper articles, public meetings and declarations of formal political groups–often obscure the real politics of regional, clan and tribal rivalries. Uzbek politics are largely a battle among the Fergana Valley, the Tashkent region and the heavily Tajik Samarkand/Bukhara region in the west. Tajiks are divided by region, Turkmens by tribe, Kazakhs by clan.

Such divisions mean that Central Asians have hazier political identities than most Soviet Europeans. Before Turkestan came under Russian control in the late 1800s, the Central Asians had developed little sense of nationality or statehood. They identified themselves primarily with their families, clans and linguistic groups–and paid the obligatory homage to an emir who could enforce fealty. The Soviets tried to break the region into distinct nationalities, largely by replacing the region’s single Arabic script with a different Cyrillic alphabet for each republic, rendering the Turkish dialects mutually illegible.

But Soviet rule appears to have left Central Asians where it found them. “A Lithuanian thinks of himself as a Lithuanian, and a Russian as a Russian,” said an Uzbek intellectual here. But, as a Central Asian, he said, “I must decide to what identity I shall be loyal: Shall I be most loyal to my clan or tribe? Or to my nationality [as an Uzbek or Tajik]? Or to Turkestan? Or to Islam?”

“THEY WANTED TO ASSERT THEMSELVES…”

Central Asia’s lack of clear political identities and political institutions that can channel political sentiment is potentially dangerous, for this region shares the volatile mix of frustrations that have bred political extremisms and violence in the Middle East and South Asia.

Part of Central Asia’s frustration is the sense of cultural failure felt elsewhere in the Islamic world. The people of Turkestan, like the Iranians and the Arabs, feel great pride in their ancient history, but humiliation at their recent past. Turkestanis claim as their ancestry the emperor Tamerlane and his celebrated capital Samarkand, the physician Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and great astronomers, mathematicians and poets of the ancient world. Many wonder unhappily how such an accomplished people fell to the low station of second-class citizens in their own lands, under Russian czarist and Soviet rule.

Central Asia long has been the Soviet Union’s poorest region. While the Baltic states have life expectancy and infant mortality rates comparable to Austria, Central Asia’s statistics resemble those of Paraguay. The population is booming and housing is short. Families in Dushanbe have waited 20 years or more for promised apartments, and rumors that Armenians were being settled in the city after the 1990 Armenian earthquake helped spark riots that left 22 dead.

Universities here pour classes of career-hungry graduates into a stagnant economy still tightly bound by Soviet bureaucracy, inefficient industrial plants and infrastructure–and virtually no capital with which to begin building. Many of these youth risk joining the frustrated class of unemployed and underemployed.

The resentments of Central Asia’s young men appears capable of being ignited–either in nationalist or Islamic guise–most easily against people seen as outsiders. The worst case of such violence was the June 1989 riots in the Fergana Valley, in which Uzbeks attacked Meskhetian Turks, an ethnic group whom Stalin exiled to the valley from Georgia during World War II. At least 115 people were killed.

Tashkent residents–recalling attacks at the city’s university that they said triggered the Fergana uprising–described the rioters’ emotions. “Students who come to Tashkent from Fergana are often outside their hometowns for the first time,” explained Aziza, who saw the riots as a student at the university. “They met foreigners here–Arab and European students–and saw that they had more money and nicer clothes. They especially could not stand it because they felt that the Uzbek girls preferred to have foreign boyfriends.”

When the Uzbek popular front, Birlik, held rallies to demand the use of Uzbek, rather than Russian, as the republic’s official language, Fergana students interpreted the message in light of their own feelings, rampaging through dorms, breaking into foreign students’ rooms, beating them and stealing their possessions. “The students … just felt humiliated and wanted to assert themselves,” Aziza said.

In Tashkent and Dushanbe, westernized Tajik and Uzbek women, with university educations, careers and a taste for some European fashions, tell privately of being accosted or spat upon by young men who, in the name of Islam, demand that they cover their hair or adopt traditional dress.

ECOLOGICAL DISASTER

The political dangers of poverty and social ills become acute when people’s hopes for improvement are dashed–a process now underway in the Soviet Union, with the unfulfilled promises of five years of perestroika.

What is worse in Central Asia is that ecological catastrophe risks a continued decline in the quality of life here.

For centuries, Central Asia was a thinly populated land whose steppes supported nomads and whose town-dwellers farmed small oases of irrigated land. As in North Africa and the Middle East, Western-style development, imposed by European colonialism, has permanently changed such societies, whose dry or desert lands now must be worked intensively to support heavy populations. But development in Central Asia was Stalinist: a grandiose campaign that sought to mold even the Asian landscape to the state’s economic plan.

Soviet planners ignored the fact that Central Asia represents a closed, finely balanced watershed, in which the Syr and Amu rivers feed the Aral Sea, the world’s fourth-largest lake. They diverted the rivers to turn steppes and deserts into a huge cotton plantation, draining away so much water that the rivers are nearly dry on their lower courses. The Aral has shrunk by a quarter–a loss of water equivalent to drying up Lake Erie–leaving a saline desert where fishing villages once thrived. Salt from the exposed seabed, whipped up by winds, now is deposited on the cotton fields.

Meanwhile, the irrigated lands have become waterlogged, their rising water tables also carrying subsurface salts to the topsoil. There, the salts mix with heavy doses of fertilizers, insecticides and defoliants used in the Soviet planning ministry’s effort to beat Mother Nature into fulfilling its quotas. The runoff from these fields, carried back to the shrunken rivers, is used for drinking and cooking by people living along the canals, producing appalling levels of illness and infant death.

Central Asians face a blunt choice: Scientists conclude that they must cut the amounts of water used for irrigation to stabilize the Aral, or see the destruction of their lands accelerate. (There is no foreseeable hope of restoring the sea, which would require halting irrigation entirely for as much as 30 years.) Yet the population is booming: the 33 million people of the four southernmost republics (excluding Kazakhstan) is expected to grow to 60 million within 20 years. The region needs a revolution in its agricultural system or a sudden drop in its birth rate, or both, to avoid a crisis of enormous proportions–but neither task will be easy.

©1991 James Rupert

James Rupert, on leave from The Washington Post’s foreign desk, is living in and reporting on Soviet Central Asia.