Photos by APF Fellow James Rupert

BAKU, Azerbaijan–In the western Azerbaijani town of Agdam, Fazil Gassimov is a respected man. He is a former school director and collective farm manager who wears his 52 years, like his sweater vest and tweed jacket, with the air of a dapper, educated gentleman.

Gassimov knows his history. As he began a lunch of shashlik, salad and vodka one day last March, he sighed sadly over the war between Azeris and Armenians in their joint homeland south of the Caucasus Mountains. History, he told a foreign guest, has recorded that in past centuries Turkic khans ruled most of what is now Azerbaijan and Armenia. That fact, certified by ruins of the khans’ castles on hilltops throughout the region, proves that the land now belongs to the Turkic Azeris, Gassimov explained. The war, over the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, was the result of treachery by the Armenians: “They arrived here only in the last generations, and we received them hospitably. We gave them land. Now they are saying that it belongs to them.”

By the end of lunch, the logic of Gassimov’s history, and perhaps of the vodka, had moved him to a vicious conclusion: “We’ll never give up Karabakh… We have chemical weapons. And, if necessary, we’ll destroy Nagorno-Karabakh completely.Then it will be our children who will come back from Baku and populate it once again. There is no other way out.”

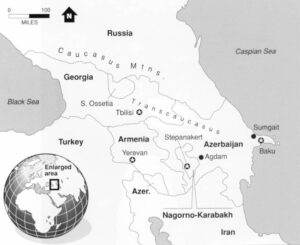

There is no clear evidence whether Azerbaijan has access to chemical weapons of the former Soviet army. In any case, of all the uncertainties reopened by last year’s collapse of the Soviet Union, the most immediately dangerous is the welter of conflicts in what was the U.S.S.R.’s southwestern corner-the Caucasus region, on the borders of Iran and Turkey. For Americans, the Caucasus is the most confusing of places-one of those gray regions Outside the mainstream of European history that American school textbooks consider our own. But the region cannot be ignored, for it is a small fulcrum that could rock larger neighbors: Russia to the north and Iran and Turkey to the south.

The Caucasus Mountains stretch like a fence between the Caspian and Black Seas-a border region that for centuries was contested by [lie empires of Russia to the north Turkey and Persia to the south. Partly because the tides of armies, colonies and refugees across these mountains and valleys, the region is a patchwork of ethnic groups. Peoples like the Armenians and Azeris-but also smaller groups, such as the Abkhaz, Chechen, Ossetians, Lezghin and Daghestanis have their own cultures, languages and even alphabets.

The Caucasus Mountains stretch like a fence between the Caspian and Black Seas-a border region that for centuries was contested by [lie empires of Russia to the north Turkey and Persia to the south. Partly because the tides of armies, colonies and refugees across these mountains and valleys, the region is a patchwork of ethnic groups. Peoples like the Armenians and Azeris-but also smaller groups, such as the Abkhaz, Chechen, Ossetians, Lezghin and Daghestanis have their own cultures, languages and even alphabets.

The conflicts among the Caucasus peoples are of a type. At innumerable places–maybe in most of the Caucasus–at least two of these groups claim the land. Like Fazil Gassimov, they cherish histories that teach that they once ruled this valley or those mountains. Often, each group feels itself a persecuted and endangered minority that needs the land to survive. Each often feels like an offended host who graciously tolerated the other as a guest, despite its own rightful claim to the land, only to have the guest declare sovereign rights. In the past few years, as the Soviet imperial grip on the Caucasus has slackened, two of the Caucasian conflicts have been carried into prolonged civil war: in Nagorno-Karabakh and between the Ossetians and Georgians in South Ossetia. Here, people fight with the mutual fear of extinction that has added years, bloodshed and hatred to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

South of the main range of the Caucasus Mountains is the region that the West calls the Transcaucasus–from the Russian zakavkaz, meaning the lands “beyond the Caucasus.” It is a land of lesser mountain ranges, many of whose valleys blossom with vineyards that produce wines and cognacs. In southwestern Azerbaijan, Karabakh (a Turkish phrase meaning “black garden”) draws its name from these vineyards. Eastern most Karabakh, where the wine-growing villages are mostly ethnic Azeri, is on the rolling plains that descend toward the Caspian Sea. But closer to the frontier with Armenia, Karabakh rises into mountains that peak at the border. In this region, called by the Russians nagorni, or “mountain” Karabakh, the villages are predominantly Armenian.

Fazil Gassimov’s history, in which Karabakh was ruled by Turkic khans, is true. But it is a partial truth, for when tides of empire washed in other directions, it was Armenian princes who governed. By the time Transcaucasia came under Russian, and then Soviet, rule, the Armenian and Azeri Turkish populations were scattered and mixed throughout it. When a border was drawn between the two Soviet republics in 1923, Nagorno-Karabakh was given to Azerbaijan-but in the form of an autonomous oblast meant to satisfy the desire of the Armenian majority there for an Armenian, rather than Azeri, identity.

Armenians never gave up their claim to Nagorno-Karabakh, which was based on their own version of its history and the Armenian majority there. Less than a year after Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev launched his policy of glasnost, Armenian demands for Nagorno-Karabakh had created grass-roots political movements. In February 1988, Nagorno-Karabakh’s legislature demanded independence from Azerbaijan and hundreds of thousands of Armenians marched in Yerevan to demand Moscow’s acquiescence. A week later, Azeris in Sumgait, near Baku, rampaged through streets and apartment buildings, killing more than two dozen Armenians. The following year, the attacks became mutual, with each side forcing villagers of the other nationality to flee their homes as refugees. In Nagorno-Karabakh, a guerrilla-style civil war began.

Armenian culture is suffused with a sense of the nation having been victimized.The 1915 massacre of Armenians by the Ottoman Turks–an act the Armenians call attempted genocide–forced them out of the heart of their traditional homeland, in eastern Turkey, and left them with a Soviet republic the size of Maryland. “We have lost so much… Naturally, all Armenians want to keep what Armenian land remains,” said Griar Arutunian, chief editor of an Armenian news agency in Yerevan.

Because of the centuries of conflict between the Christian Armenians and the Muslim Turks-and especially because of the massacre, in which Armenians say as many as 1.5 million were killed–a dislike, even a demonization, of Turks is part of Armenian culture. Most Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh “find it impossible to have any belief in the good faith of any Azerbaijani,” said Anatoly Shabad, a member of the Russian legislature’s human rights committee who has spent months in the territory monitoring the conflict. “It is ingrained in them,” he said. “Armenian women frighten their children with the name of Turks.”

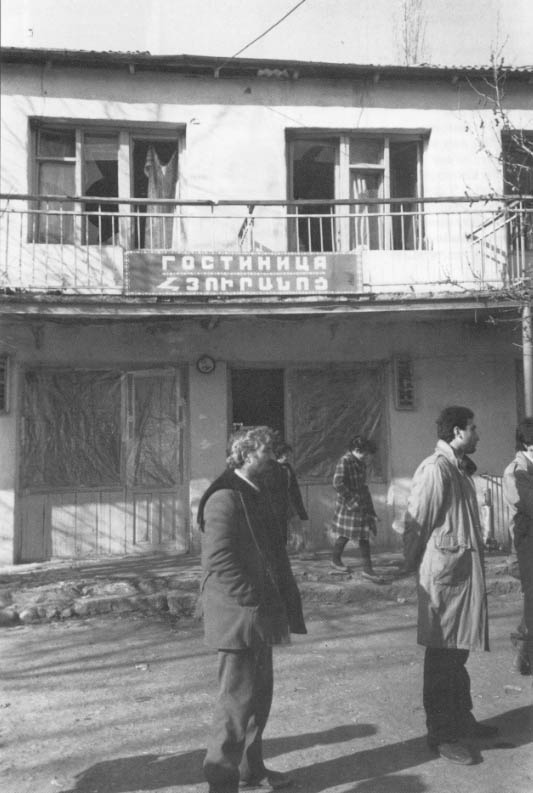

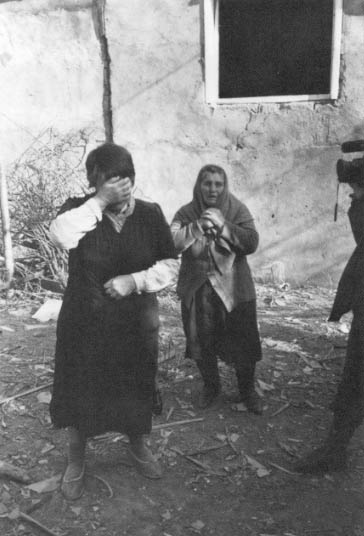

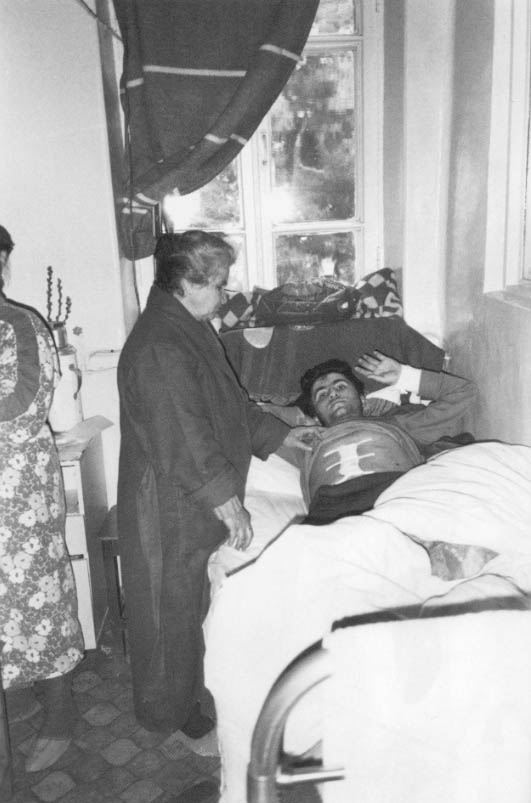

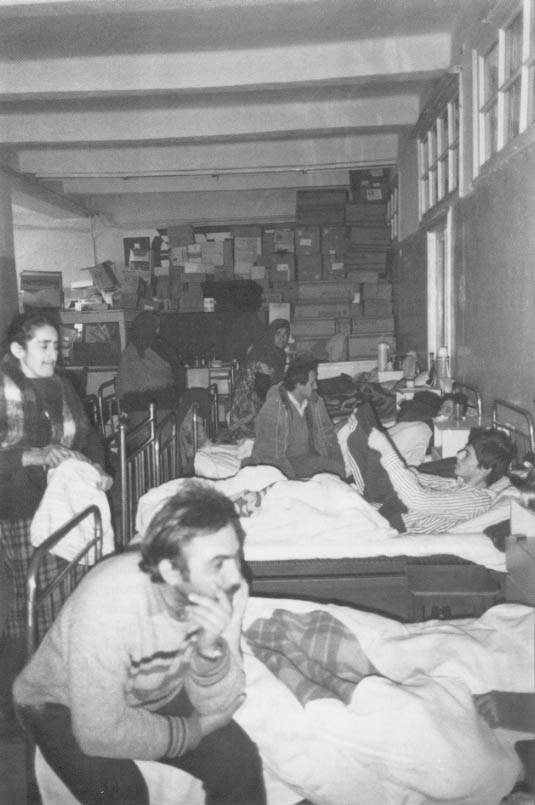

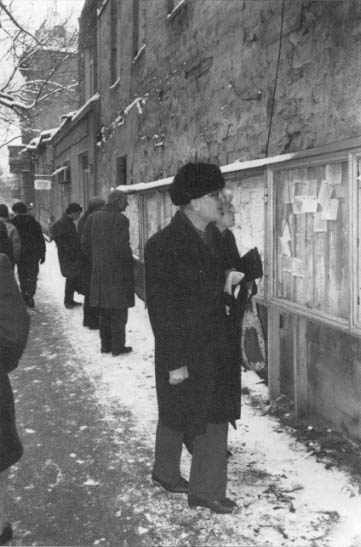

In January, among Armenians living in Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital, Stepanakert, the historical hatreds were sharpened by immediate desperation. The city of 70,000 was covered in snow, yet bad no heating oil, electricity or running water because of Azerbaijan’s blockade of the territory. Worse were Azeri rocket salvos, which demolished homes and killed residents by night, and sniper attacks that picked off people in the streets by day. Jana Dzhangirian–a white-haired grandmother who spent her days fussing over her grandsons, ages five and two–raised her soft voice only to berate the Azeris: “They were Turks and they’re still Turks…They were. animals and they’ll remain animals.They’re uncivilized.” The Armenian characterization of Azeris as “uncivilized” is often muted to an emphasis on the Armenians’ own attachment to the Christian and western worlds, in contrast to the Azeris’ place in the Muslim community.

Dzhangirian’s son, Karen, an official of the Nagorno-Karabakh government, avoided his mother’s vituperation of the Azeris. But, walking through the shell-shattered, lifeless streets of Stepanakert on a bitter January morning, Dzhangirian contemplated the blockade that was draining the city’s food supplies-including the winter stores he and his wife had put up in their garage last fall. “If tomorrow my child asks me for bread, shall I tell him, ‘Wait a little bit while the world deals with Yugoslavia first, and then they’ll send the United Nations to lift the blockade here?’” he asked. “No. I will go out and take the bread from my Azerbaijani neighbor-and maybe I’ll have to kill him to get it.”

Before the Soviet revolution, the Azeris largely saw themselves as Turks, and still feel a close identity with Turkey. But by giving the Azerbaijanis their first long-lived, unified state, Soviet rule strengthened their national identity. Yet the Azeris feel themselves surrounded by adversaries that are trying to prevent their rise to real independence. Iran, many Azeris say, opposes them because their independence offers a dangerous model for the millions of Iranian Azeris, across the border. Russia, which ruled Azerbaijan as czarist empire and then as the central power of the Soviet Union for 178 years, is seen as their old oppressor. “Russia is helping the Armenians as a way of keeping us suppressed,” said Elha Rustamov, correspondent for the official Azerbaijani news agency in Agdam. “Russia is afraid that our independence will be a model for other Turkic” peoples in the former Soviet Union to challenge Russian interests, he said.

Azeris also share a nonspecific but strong belief that the United States and Europe have been drawn into a conspiracy against them by the influence of the global Armenian diaspora. “There is an Armenian governor in California,” (former governor) Edward Deukmejian, said Gabil Gusseinov, a political science professor and commentator for Azeri state television, “and we know there are Armenians in Congress.” Neither Gusseinov nor others cited actions by the West that showed a bias toward Armenia, but declared their case proven by the fact that Armenia’s new foreign minister, Rafi Hovanissian, is an American citizen and former congressional staffer. Rustamov and other Azeris flatly asserted that western television news reports showing the heavy damage to Stepanakert had really been filmed in the nearby Azeri town of Shusha and had been mislabeled to discredit Azerbaijan.

At an Azeri front-fine guardpost near Agdam, a group of Azeri militiamen, in combat fatigues and with automatic rifles slung over their shoulders, watched one day in March as a French diplomatic convoy returned from Stepanakert. When the trucks halted, grizzled guerrillas pressed to the open window of French Deputy Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner. They had a question: Had the minister seen evidence that Azeri forces were attacking civilians, as the Western press said? Could he truthfully say he had seen any destroyed houses in Stepanakert?

Kouchner gaped in astonishment. “I don’t want to answer such questions,” he said indignantly. But Michel Bonnot, head of the French Foreign Ministry’s European section, was more vocal. As the truck lurched forward, he leaned out of his window and shouted back: ‘The city is being destroyed! People are living in basements!” Watching the trucks pull away, the guerrillas shook their heads. They knew with certainty that it was the Armenians who killed civilians and shelled houses in this war-not the Azeris. If the French were, saying otherwise, they said, it showed that they had taken the Armenians’ side.

The belief in conspiracies is linked to the Azeris’ own demonic image of the Armenians. Numerous Azeris did not hesitate to label Armenians as cunning, sly people who gain advantage by connections and deception. “You know, they always lived better than we did,” said Rustamov. “People always talk about Sumgait,” site of the 1988 massacre of Armenians, “but they don’t understand the way that they (the Azeris) felt. You should have seen how they (the Armenians) lived there.”

Azeris say they cannot give up Nagorno-Karabakh because the Armenians would then press other demands. “They say they have the right to the western half of Azerbaijan because some people lived there hundreds of years ago,” said Capt. Mirsalikh Akhundov, a spokesman for the Azerbaijani Defense Ministry. “If they take Karabakh, then they’ll want more and more, until they’re right here in Baku,” Akhundov said. To an outsider, it may seem an exaggerated fear–but the independence claim by the Armenian government based in Stepanakert includes not only the former Nagorno-Karabakh autonomous oblast, but an Armenian-majority district to the north that always was part of Azerbaijan proper. And there are historical Armenian claims to other parts of Azerbaijan, even if no prominent Armenians are pressing them now. (As are so many others, this part of the conflict is symmetrical; Fazil Gassimov, the Azeri history buff, stresses that the Armenian capital, “Yerevan, really is ours. There were khans there, too.”)

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict carries risks beyond the vineyards of the Transcaucasus. During the spring, Turks held anti-Armenian marches in several cities, and Turkey’s prime minister called President George Bush to say that Turkey would be unable to stand aloof from the conflict if it continued to escalate. Iran tried to mediate in the war, clearly concerned over its effects on Iranian Azeris.

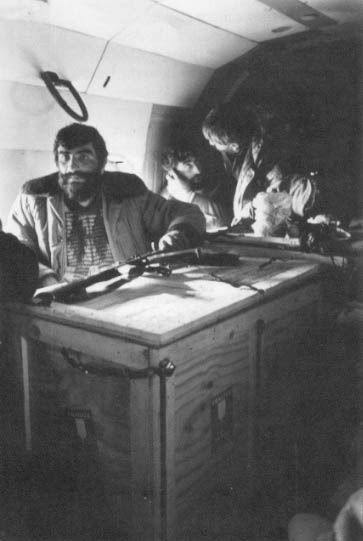

The Russian-led ex-Soviet army tried to withdraw its last regiment from Nagorno-Karabakh, but the unit broke apart, with top officers accepting an airlift. to Georgia and many others choosing to take their weapons to fight on behalf of one side or the other. Both Azeris and Armenians hoped, after a March visit by U.N. special envoy Cyrus Vance, that peace-keeping forces might be sent from the United Nations or the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe. With each side in the conflict carrying a badly distorted sense of reality, and with no strong and acceptable mediator in the region, the international community does seem the only hope. Yet it now is barely able to pay for peacekeeping efforts in Cambodia and Yugoslavia.

Karabakh’s near future is probably depicted by its recent past-and the passions that drive it are repeated with alarming regularity in the Caucasus, Through the spring, the South Ossetian war continued to resemble a small Karabakh, limited only by the smaller populations involved and the fact that their weapons are lighter–mostly rifles, machine guns, and shoulder-fired rockets. The Ingush continued to threaten possible violence over their claim to part of North Ossetia.The Chechen trained an army to fight for independence from Russia. Caucasus Cossacks held meetings to demand their own national territory.

The last time that the Caucasus was free to pursue its own patterns of life and conflict, it had no modern armies with which to do so, and there were no electronic communications to make its actions so relevant, and therefore dangerous, for neighboring countries. It will never be so easily ignored as it once was.

© 1992 James Rupert

James Rupert, on leave from the Washington Post’s foreign desk, is reporting on Soviet Central Asia.