Michael Harrington once wrote that one ought not to talk about “poverty” but about poverties. He meant there are so many ways of being poor that no single description or analysis can apply to them all. The same thing is true of homelessness. There are in actuality a variety of homelessnesses, each one different from the others in terms of causes, particulars and solutions.

What I want to do here is describe a particular kind of homelessness, one that has gotten less attention than it deserves: a sporadic and recurrent homelessness so much a part of the cycle of poverty in which some people find themselves that it becomes a predictable and “normal” part of their lives.

Ordinarily we think of homelessness in other ways: as either the result of a long downward slide (as with alcoholics, for example), or else as the result of a cataclysmic event-catastrophic illness, mental collapse, the sudden loss of a job or a home. In both cases homelessness seems like a sudden and forced exile, almost a falling off the earth, something that takes people beyond our ordinary social or economic orders and into another and an alien reality.

But there is another kind of homelessness, one that very poor people learn to take almost for granted. It’s a part of our social and economic orders, part of the poverty which takes people, in a seemingly endless round, in and out of homelessness: from low-paying jobs to unemployment to shelters to the street to welfare to low-paying jobs and eventually, once more, to unemployment and the street.

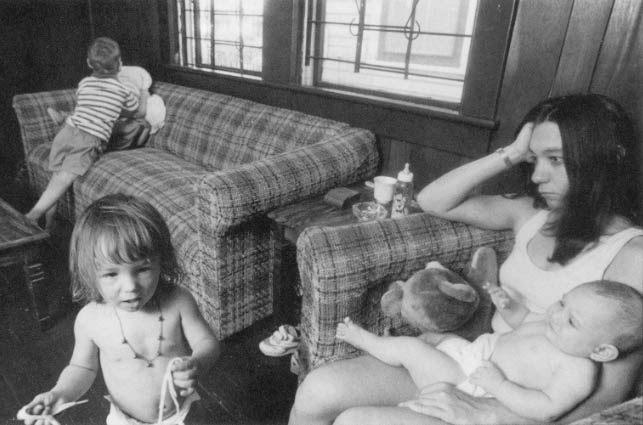

I want to examine that form of homelessness by writing about a young African-American woman named Virginia who I met several years ago in New Orleans. She was then twenty-one, with two young children, and she had just gotten out of a shelter after being homeless for a year. Since that time she’s been homeless three times or more and when she hasn’t been homeless she’s been so close to its edge, that it took only the slightest mishap or mis-step to make her homeless again.

There is another reason, too, I want to write about Virginia. For several years now advocates have concentrated on the absence of affordable housing or low wages as the main causes of homelessness. But there is far more to most kinds of homelessness than that. If you carefully examine them, you find at work psychological, social and cultural factors as well as economic ones. And it is only in that larger context, that you can understand what homelessness involves, or how and why people become homeless.

Is Virginia’s case typical? I don’t know. The statistics we have about homelessness don’t usually tell us precisely how long or how often particular people are homeless. But I do know this: Virginia is an African-American, and close to 50 percent of the homeless population (more, in large cities) is now African-American. And Virginia is a young single mother without skills, prospects or a mate, and a goodly portion of the families now on our streets or on welfare is headed by women in similar circumstances.

I first met Virginia when I went down to New Orleans to talk about homelessness at a conference of city administrators. I asked a local homeless advocate to suggest a couple of people who could come to the conference and talk about their lives. One of them turned out to be Virginia, who was then in a short-term church-run program for homeless mothers in which she had been given an apartment for three months and help in finding a job.

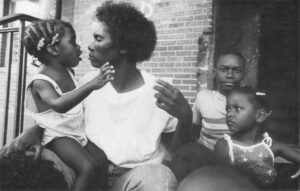

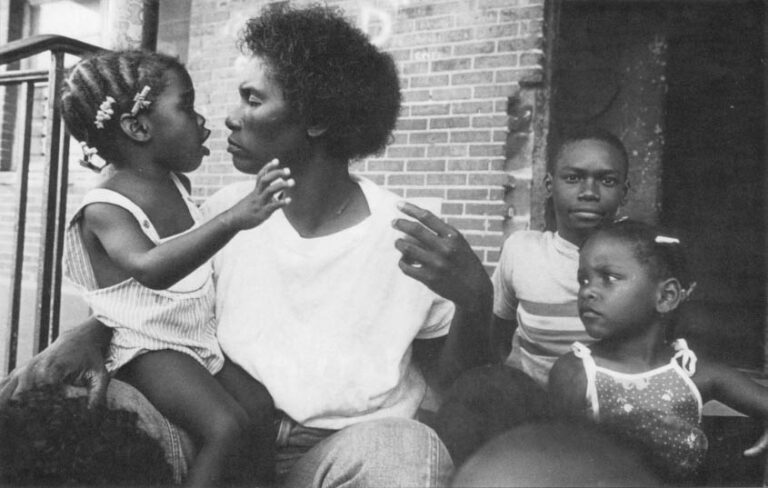

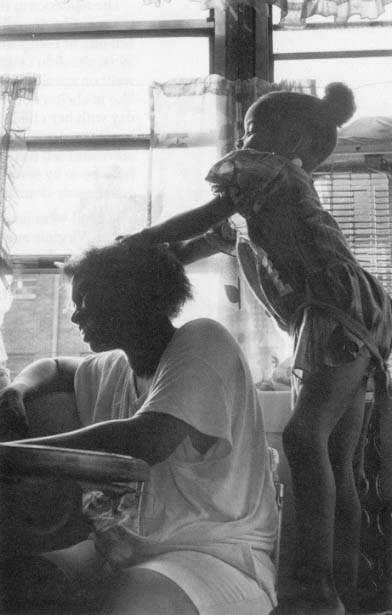

I know enough about black-white relations in the South to understand the guardedness and masking that goes on, so my sense of Virginia is largely limited by what she let me see, but I liked her from the start. She was tall and slim with a soft face and high check-bones and her hair cut boyishly short. There was both gentleness and directness in her manner, and a kind of shy diffidence, and she seemed, as do many young women in the South when faced with people who have power over them, to draw her voice-and her whole being too-inward with her breath as she spoke, so that you felt yourself leaning forward, straining to hear, even when you heard her words clearly.

The audience at the conference liked her too. She described her life without self-pity or complaint. Facts followed facts; she didn’t editorialize; and as she went on speaking, describing what it was like in shelters or walking the streets all day with her children, the people listening were moved, perhaps more by her sorrowful self-possession than they might have been by something more shrill or consciously dramatic.

When I went back to my family in California, Virginia and I kept in touch. Whenever she was in financial difficulty she’d call and I’d wire what money I could. I’d been well-paid for my lecture and Virginia had gotten much less and it seemed only right to send her what she needed until I’d exhausted my fee. Week after week, month after month, I followed, long-distance, the twists and turns of her fortunes. Whenever I went down to New Orleans, I would see her and we’d talk, and then, last summer, I went to New Orleans to write about women who were homeless or on welfare, and I had a chance to see, close up, Virginia’s struggle to get by.

It doesn’t take long, looking at the economic details of that struggle, to realize why it was so easy for Virginia to slip so often into homelessness.

Virginia’s welfare payments were $190 per month. That’s what the state of Louisiana gives to a woman with two children. With one child, you get $169. With three, you get about $235. For every other child, your check increases by about $50, but the total is clearly never enough to lift you out of the worst kind of poverty.

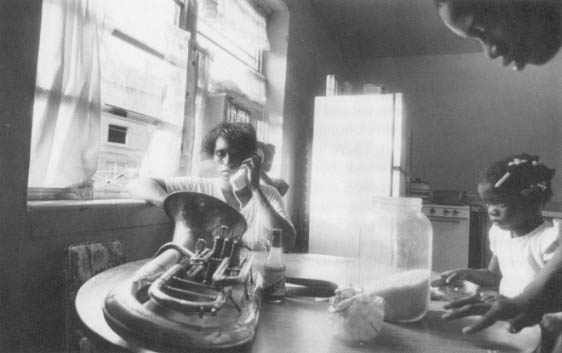

Measure Virginia’s payment against her expenses. When the church program ended, she stayed on in her apartment, and it cost her $150 a month. Her utilities came to $100. A telephone was a necessity-both for looking for work and keeping in touch with the world. That was another $30 or so, at a minimum. Food stamps provided her food, but even so her basic expenses came to $280 a month, and she was $90 behind before spending a penny on clothing, toys or transportation.

Virginia looked for work. But all she could find were part-time split-shift jobs at fast food outlets for minimum wage. Employers in New Orleans prefer part-time and split-shift employees because that keeps the cost of benefits low and means you don’t have to pay overtime wages. Say Virginia worked 20 hours a week for $3.35 an hour. That’s $60 a week in take home pay. But she had to pay someone to watch her children, and when you deduct that from her pay and throw in the cost of transportation – $I0 a week – there wasn’t much left at all.

Then there are welfare regulations. The federal government requires, by law, that any money you make must be reported to the welfare office so that the same amount can be deducted from your next monthly check. That means that for every dollar you make, you lose a dollar, so you’re left, always, in the same sorry predicament. And if you don’t report your earnings – as sometimes Virginia did not – then you are, according to the law, guilty of fraud.

What happened to Virginia was predictable and inevitable, She fell further behind on her bills. First the telephone was disconnected; then her utilities were cut off. Finally she stopped paying the rent altogether and was evicted. Homeless again, she went back to the same shelter she’d been in before she entered the church program. For several months, she looked unsuccessfully for work. And then she chose the only option left open to her and did what almost everyone on welfare in New Orleans ends up doing: she put her name down on the waiting-list for an apartment in the city’s “projects” and took the first one that became available.

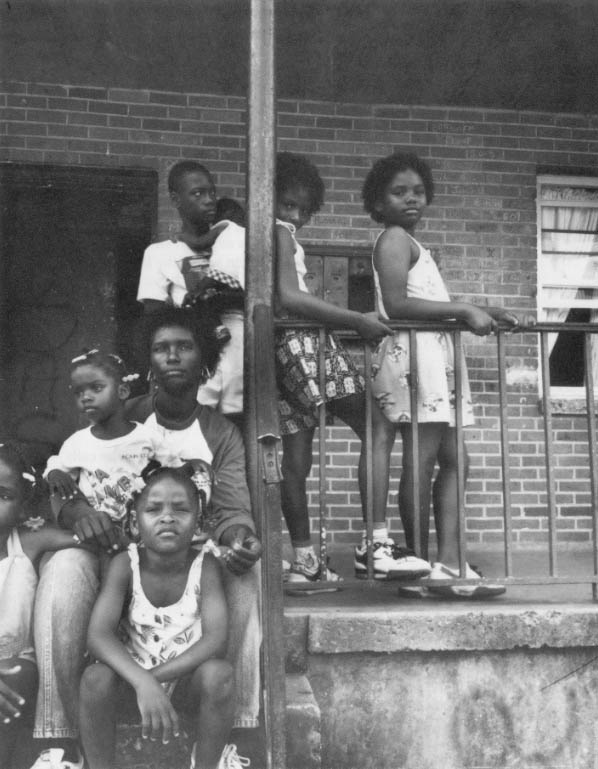

There are about a dozen projects scattered throughout New Orleans: huge federally funded housing developments built in the 1930’s and 40’s and now administered by the city. Official estimates put the number of people in the projects at 55,000, almost all of them black, most of them on welfare. But homeless advocates and grass-roots leaders estimate that when you add in illegal residents and doubled-up families you get a total closer to 75,000 or even 90,000, which would be close to 25 percent of the city’s 330,000 black inhabitants.

I’ve seen old picture postcards of the projects: neat lawns and tidy two and three-story brick buildings surrounded by trees, street-lamps and wrought-iron benches. These days they’re dusty and run-down wastelands largely ignored by the city government which administers them. In some projects a third of the apartments are gutted and abandoned; drugs and guns abound; violence is common-place and at night you often hear gun-fire. When Virginia lived in the projects she kept her windows boarded up so the gangs wouldn’t bother her and she wouldn’t let the children play outside. “Minute I’d let them out,” she said, “I’d hear shootin’ and they come runnin’ inside. I always told them to git down low and don’t be scared.”

For those who live there, it’s the meanest kind of life. The only reason for moving in is economic, and once you’re there it isn’t easy to get out. Look again at the figures and you see why. Rents in the projects are geared to income, and Virginia’s apartment, utilities included, cost her $60 a month. Figure, again, $30 for a phone. Assume that food-stamps provide food. That leaves $25 a week for all her other expenses. That is more than you’d have living outside the projects. And if you teach yourself to need little and expect nothing, you can last forever in the projects, impoverished and in constant danger, but at least off the streets.

But Virginia didn’t last. She missed a couple of welfare appointments and her checks stopped for several months. She didn’t pay the rent and was evicted. Homeless again, she went to stay with an older woman-friend whose one-bedroom apartment was paid for by a lover. Virginia and the boys slept on a fold-out couch in the living room and got all of their meals, in return for which Virginia signed over her now-restored welfare checks to her friend. She was, she told me later, a virtual prisoner. But even that didn’t last. The boyfriend grew tired of her presence, and her friend told her to leave.

You already can see, how Virginia was checked at every turn by economic factors beyond her control; rents she could not afford, the scarcity of decent jobs and welfare payments so low they amount to a kind of indentured pauperism.

But there also is more to her situation. As important as economic factors are, they do not tell the whole story behind Virginia’s situation and fully reveal the difficulties she faced.

The easiest way to explain is to describe Virginia’s early life.

She grew up in New Orleans when the city to hear Virginia and others tell it-was more prosperous, neighborly, orderly and livable than it is now. The black neighborhoods were then thriving, and though whites had not yet fled the city to the suburbs, both inexpensive housing and decent jobs were easier to come by than they are now.

Virginia had four sisters and two brothers and a mother who took good care of them and a father who drank a bit too much but worked steadily on the docks as a foreman and had managed to buy a small house. But when Virginia was seven, her world fell apart. Her mother died. Her father’s drinking increased. Her two older sisters and a brother left the house. At eleven, she was left in the house with a younger brother and sister. “My daddy was gone all the time,” she says. “We was in the house by ourselfs many a night. We never knew where he was cause he didn’t want us knowin’ his business.”

Then Virginia’s father was shot and wounded in a bar by a jealous woman. He lost his job. The house was sold at auction and Virginia and the other two children moved in with an older sister who had joined the Army. She sent Virginia to a Catholic day school. The father disappeared, perpetually drunk, on the streets of the city. Virginia’s oldest brother became her surrogate father. And then he was shot five times and killed in a barroom brawl.

Virginia managed to graduate from high school-but in her senior year she fell in love with a boy and was soon pregnant. She had the baby after finishing school and stayed on with her sister. Then she met another man and got pregnant again. Neither of the men could take care of her. Neither wanted to marry her. Both went off, but Virginia shows no anger when she talks about them: “I don’t bear them no grudge in my mind.”

Of the first one, she says: “He tried. He wanted to be a man. But he couldn’t find no job or nothin’. He got discouraged and got hisself in trouble. I think he was misled to wrongness.”

Of the second, she says: “He never had no chance. He grew up in the projects not carin’ about things. That was his lifestyle. Now he got another baby by a woman younger than me.”

When I ask about birth control, she says: “See, when you’re just startin’ out you don’t know what you do now. I was only nineteen, and a good girl, and my sister, she kept that stuff quiet.”

When Virginia had her second child, her sister told her she couldn’t take care of her anymore. Virginia went to a Salvation Army shelter and then, after several months, into the church program she was in when I met her.

There’s nothing in Virginia’s story that is unusual-not at least in terms of the stories I heard in New Orleans from other women. All of them had in them many of the same elements one finds in Virginia’s story: early pregnancies; men drifting in and out; little preparation for work or the world; little family support or an end to it; and, perhaps most importantly, personal tragedies and traumas which had destroyed an orderly world or deprived people of the sustenance they needed.

I think here about a thirty-five year-old woman in the projects named Lobelia who had had eight children by six different men. She was tough and outwardly cheerful and had been hooked twice on drugs but was clean when I met her and trying hard to replace crack with Christ. She had a 20-inch scar on her thigh from a recent fight with a neighbor over a man, and she wouldn’t, she told me, let any male visitor into the house unless he brought whiskey, food or money. “I ain’t no whore,” she said.

I didn’t quite know what to make of her until she told me one day that her father had died when she was thirteen. “I went so wild with grief,” she said, “there wasn’t no controlling me. My mama had the doctor declare me crazy and they put me away for a year.”

When she got out she immediately started having sex and children and soon her mother would have nothing to do with her and she went from one relative to the next until, homeless and on welfare, she went into the projects.

Mixed in with economic troubles are these other difficulties: sorrows of the heart and grievances of the soul which isolate men and women and make it impossible for them to make order in their lives or sense of the world. Is that a surprise? Jack London, long ago, in People of the Abyss, perhaps the best book ever written about the poor, speculated that in a competitive and individualized economic system those who failed soonest were those, without the energy and will, as well as the means, to survive. What I’m saying here is delicately different: that those who have had the hardest time surviving are neither the weakest nor the worst but often those with the least sense of human connectedness, the strongest senses of betrayal: the wounded, the abandoned, the excluded, the abused, all those who cannot on their own discover how to fit in or even the reason for trying. I remember once asking Virginia what she most wanted in the world. I expected her to say something about money or a house or a job or a man. Instead, she said in a voice so soft I had to bend to hear: “I want my Momma to be livin.”

Almost all of the women I spoke to in New Orleans had had two or sometimes three sets of children by different men, almost all of them outside marriage. Most women had their first children in their middle or late teens, often with men they say they loved. Birth control isn’t much talked about or used; abortion hasn’t much appeal; and since most of the young men involved are without money, jobs, skills or prospects, going on welfare is, for most of the women, the only possible choice.

Here too, welfare regulations play a role. For decades, family aid has gone only to those households where women and children lived without men. Where men are present-even husbands and natural fathers-no aid is given. Precisely how much effect this had had in poor communities has not, in so far as I know, been documented. But the regulations may have destroyed or nullified whatever impulses men and women may have had to stay together.

Once on welfare and in the projects, women are almost like hostages: bored, tied down by children, isolated from the larger world and with little hope of changing their lives. They become stationary targets for disenfranchised men for whom sex is an anodyne and a consolation and a way of proving one’s worth or simply that one exists. Out of boredom and the human need for company, attention and pleasure, more children are born.

There also is the fact that children in the South, and especially among the poor, seem to have an absolute value that often makes abortion unthinkable.

I remember a conversation I had with Tanya, a young woman in her late twenties who was a second generation project dweller. She had had three children by two different men-friends. One of them, a daughter, was still a nursing infant. Now she was pregnant again. The father was a man she hardly knew and didn’t like, and she had slept with him while drunk and without precautions, believing – as do many women in the South – that she couldn’t conceive as long as she kept suckling the child. “It wasn’t quite rape,” she said. I just lay there, not ready, not caring. But I didn’t bother to say no.”

But still she could not bring herself to have an abortion. She’d gone twice to a birth-control clinic intending to get one, but couldn’t go through with it. And then her own doctor let her listen to the fetal heart-beat with a stethoscope. After that, she said, I couldn’t do nothing. It was like my own heart I heard.” And then she sat there, musing, and asked me again and again, “Would someone like you like me if I had an abortion? Do you think God would like me?”

A few days later I met with Jeannine, whose father was a school-teacher. She had wanted to be a journalist. But in her first year at college she fell in love and got pregnant and now she had four children by two dads. She had recently had an abortion. “You know,” she said, I hate my life. I hate myself for wasting it. I’m so depressed I once tried to give the kids away for adoption. But the very worst time in my life was when I had the abortion. I didn’t want the baby. I knew I shouldn’t have it. But afterwards, well, when I came back, that’s when I tried to kill myself.”

Religion? Tradition? The fear of God? The inherited, forced and oppressive notion, of women merely as mothers, as breeders? I don’t know. Perhaps. Certainly at times, talking to these women, I had a sense that they were trapped not only economically, but also in roles and traditions they’ve inherited rather than chosen.

And yet these families, which echo the large families from which these beleaguered women come, provide at least some sense of connection to the past, some sense of purpose and home in troubled lives which might otherwise be too empty and crimped to bear.

I remember a conversation I had with Tanya’s two older children-a boy of ten, a girl of eight. They told me that between them they had two daddies and considered one of Tanya’s boyfriends to be a third.They felt that all of their daddies’ other children by other women were their brothers and sisters-eight in all, they said, toting it up on their fingers. And some of the mothers of those children had become their surrogate aunts, and the children of those women by still other men were, they thought, like their cousins-all part of a web extending outward and endlessly expanded by the formation of new sexual relationships and the birth of new babies.

Within this network, relationships were not always determined by biology. Tanya’s son, for instance, felt closer to his sister’s natural father than he did to his own. They spent part of each summer together. The sister, in turn, spent much of her time at the house of her brother’s daddy’s new girlfriend, who, she said, she had started to love.

Hard to follow? It’s true that when I asked the kids whether they wouldn’t have had one permanent father there all the time they wistfully nodded yes. But nonetheless these families work. They aren’t just a break-down of what we think of as normal family life, but a variation of them: a system of connection that acts as a buffer against loneliness and creates not only a meaning for life but also a social world, a human world. Seen in one way, they are evidence of a culture in trouble; but seen in another way they are a way of continuing and extending that culture, a way of keeping it alive.

There are other elements at work in Virginia’s life: culture and racism. I link the two together because it isn’t easy to separate them in the South-not from the outside, not as a white person peering into a black world. There are certain things to which African-Americans in the South-and especially in the projects-seem to cling: language, music, large families, etc. But since the people and the projects are ringed by a still-racist society, one can’t tell precisely what they’d keep or leave behind were they free to choose. Given that, one can only give a rough indication of how both are at work in lives like Virginia’s: a culture which sustains people and a pervasive racism that forces people into a closed and unhappy world.

Talk to Virginia about this and she stays pretty mum. These are not things you discuss with white people. But I know how wary Virginia is when she and I walk downtown or sit together in a restaurant. She wants it to be perfectly clear to people there’s nothing romantic or sexual between us; but she’s also worried that people will think she’s a whore and that it’s merely business between us. That isn’t paranoia. Black and white don’t usually mix in New Orleans, and certainly not two by two. No matter what the law of the land says, every black person in New Orleans, or the entire South for that matter, of maybe all America, know there remain two separate worlds and a set of invisible “pass-book” rules nowhere written down but everywhere in effect.

How much does all of this enter into Virginia’s troubles? No one can say. But surely it is not surprising if she often acts ineffectively or without much aggressiveness in a world which is still, as she understands it, off-limits to her. She is expected somehow, all on her own, to succeed in a world from which she was systematically excluded as a child. and in which, in her mind, she has no place.

What about rage? About this subject too Virginia remains self-protectively silent, though it would hardly be surprising if she felt a cumulative fury with white welfare workers, white shelter providers, white employers, white apartment managers and, yes, even with me – a white man supposedly expert, at a very safe distance, in the reality she experiences every day.

Too, there is the whole question of culture. Debates about African-American culture rage everywhere, and all black men and women are individually faced with agonizing choices pertaining to culture and tradition: how much to embrace, how much to discard, how to mediate between their needs for a culture and the sense that it must be discarded. There’s a growing sense in African-American intellectual and academic circles that the trade-offs required of those who want to find or keep places in mainstream America may be a bad bargain, at best, and that the gains to be had are matched by what is lost in terms of your senses of identity, self, community, and the past.

For most black Americans, a terrible tension exists. For the pull of the past is there, especially in the South, where some of the sustaining traditions of black culture remain partially intact. There’s a whole world in the projects which outsiders cannot enter. But you can sense it, from outside. It’s there in the language, a patois so private, so dense, that it is like listening to a foreign language. It’s there in the music, in the systems of kinship, in the perception of time and space, in attitudes towards pleasure, work, leisure and community. It’s there in the still astonishing capacity for generosity and sweetness, in the residual passion for relationship rather than competition, in a system of values that somehow raises life itself to a crowning position unchallenged by success or accumulation.

Obviously, the culture I’m describing is in disarray. Most of those who maintain it do so in part because they have little choice. But if they hold tight to it, unwilling to let it go, that’s natural enough. Look around. There’s something so joyless and pained about the society we expect people to enter, that one can easily understand why-in cultural if not economic terms-some men and women are reluctant to enter it, or to trade away what little they have for the little we offer in return.

Much of this applies to Virginia. It’s in her background and it exists side by side with, the more obvious issues of rents and wages. Erik Ericson, writing about Martin Luther, once argued that certain great men were culturally significant because they are forced to resolve in themselves deep-seated and schismatic cultural crises. The same can be said of more ordinary people, Virginia, for instance, though in her life, as in others, it is failure rather than success that we see, as if some people suffer in themselves cultural crises they cannot, on their own, resolve, or heal. Certain kinds of homelessness attest to that.

But Virginia, of course, has not failed yet. Her story so far has neither an unhappy nor a happy ending. I go back now to where she was when I first saw her last summer, on the living-room couch at her friend’s apartment, about to leave and with nowhere to go.

Had I not been there, she might have been homeless again. But she had one welfare check in hand and asked me for a loan of.$200. With the total, she said, she’d be able to move into an apartment. I tried to tell here there was no point in it, that even if she got a place -he couldn’t keep up the rent payments and would be out on the street in two months. “I don’t care,” she said. “I ain’t going back to the shelter. And I got a feeling this time that somethin’ good is gonna happen.”

One Sunday with newspaper in hand we went hunting for apartments. Virginia wanted to get as far away from the projects as possible, so we drove out to an area known as East New Orleans on the city’s edge. Only a few years ago, developers moved into what had been rural territory and began building housing developments and apartment complexes for an anticipated invasion of baby boomers that never materialized. The rents are low and there are still open spaces and stands of trees and, at twilight, a whole host of country smells, though it is only twenty minutes by bus “a straight shot,” says Virginia-to downtown New Orleans.

We had only to look at two places before Virginia found what she wanted: a rather dingy one-bedroom apartment in a colonial-style complex with a brimming but dirty pool, a laundry room, and both black and white tenants. The ad in the paper had something about moving in for $199, but I let Virginia talk to the manager alone, and when she emerged she had handed over $400-$235 for the first month’s rent and the rest, he had explained to her mysteriously, for “one-time unrefundable charges.”

The apartment was on the first floor, out on the edge of the complex where the blacks were put. It had a glass door in the living room that slid open to a swampy common that once was a lawn. The whole place smelled of mildew and mold and you could see its speckled presence on the wall a couple of feet above the damp shag carpet. But Virginia loved it. It was the nicest place she’d lived in, she said, “since my daddy’s house.” The manager who had overcharged her took a liking to her-it was the South, after all-and dragged out of storage an old box-spring and two torn high-backed velvet chairs and a lopsided table that non-paying tenants had left behind. Said Virginia: “It’s mine, my own, my first real home.”

And then, to my surprise, something good did happen. Virginia had a friend who worked as a maid at a downtown hotel, and for more than a year she had called the hotel every few weeks to see if there was a job for her. Three days after she moved into the apartment she called again and they told her that if she came in the next day to be interviewed, they would put her to work.

Within a week she had a steady job and had found someone to watch her children. It was a good job as such jobs go. The hotel was locally owned and the owners treated their employees in a familial way, The pay was close to $5 an hour and there were scheduled raises and a health-plan and a credit union and below cost hot lunches in the cafeteria. It was clear, Virginia told me, that if you did your work and showed up on time, you could stay there a lifetime. “You’re gonna have to show me,” she said excitedly, “how to open a bank account and write checks and save. I never done it before.”

But there was one small hitch. Your hours and pay weren’t steady. In the winter when the hotel was full you might work seven hours a day, six days a week-forty-two hours in all. But in the summer when the flow of tourists slowed, you might work only three or four days a week, and only five or six hours a day.

Now, for the last time, look at the figures. During the busy season Virginia can take home perhaps $700 a month. Measured against her expenses that doesn’t work out badly. $235 for rent, $100 for utilities, $30 for the phone, $30 for transportation to work, $25 for hot lunches-it comes to $430 or so a month. With her earnings, she won’t get food-stamps, but that still leaves her about $65 a week for food, clothing, toys, etc. Maybe if she’s disciplined and lucky she will, as she said, be able to save.

But what happens when things slow down? Figure four days one week, three the next, say fifteen days a month, maybe six hours a day. That’s about $400 a month in take-home pay, not quite enough to cover her expenses, though they’ll be slightly lower. She’ll get some food-stamps if she reapplies for them every time her income dips. But what about other expenses? It isn’t hard to imagine what will happen, just as it’s happened before. She’ll fall behind; the phone will be cut off; the lights will go; there’ll be a monthly struggle to come up with the rent, and when she fails to do it, the eviction notices will start, and sooner or later, she’ll be homeless again.

That hasn’t happened yet. Virginia still calls, though less than she once did, and less in need of money than of the sense that someone cares what happens to her. But she’s having trouble making do. The tourist season is over and she’s working less-four days in two of the last three weeks, she told me. She has a bit of money saved and the manager of her complex tries to give her odd jobs around the place, but what she really needs is what nobody poor in America gets: a loan to tide her over, or welfare money to supplement her salary, or some kind of grant so that she can learn to do something else.

What comes to my mind when she calls is an image I first had years ago, during the period when she was in the projects. She’d called me up in despair, at the end of her rope. She hadn’t wanted money. Instead she asked for something else. “Kin we come live with you,” she said, “kin we come live with you?”

I said no, I was sorry, and I sent her some money, and the image which came to me then and which is with me still was from Moby Dick, when at the end of the book the Pequod sinks beneath the waves, and every imaginable oppressed and immigrant color and race is sacrificed to mad Ahab’s white power, will and rage. I kept imagining Virginia among them, calling out from the sea: “Kin we come live with you?”

Maybe that’s over-dramatic. After all, Virginia is still afloat. And maybe, just maybe, since homelessness has become such a “natural” part of her life, it isn’t in her mind quite like sinking, but is instead simply a way of getting from one of the familiar stages of poverty to another.

But I’m not sure. Virginia keeps her sorrows hidden, and I’ve never seen the full depth of the desperation she feels. And how long can she keep it up? How long before tiredness or hopelessness wear her down, or before she begins to solace herself with alcohol or drugs or sex, or before, with a sigh, she lets herself slip back into the stasis and safety of welfare and the projects? And what about Virginia’s children? What’s the cost to them of all of this? What happens to them if she becomes homeless again or decides to seek permanent refuge in the projects?

So the image of sinking persists: Virginia, along with millions of others caught in the swirling currents of poverties and homelessnesses, each on their own, but together somehow in the downward spiral of their fates. The modern equivalents of Ahab’s madness are all around us, spelled out for us in the ghettoes and projects of America. Economics? Yes. Of course. Wages and rents? Obviously. But the crisis goes so much deeper, and the wounds are so much more varied, it would take another Melville to catalog and reveal them all.

© 1992 Peter Marin

Peter Marin, a freelance writer in Santa Barbara, California, is examining homelessness in America.