On Seventeenth Street, just a short walk from the White House, is a handsome, five-story building that is one of the oldest government offices in Washington. Appropriately, it houses the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), which deals with an issue that has bedeviled the United States since its founding days. The American Revolution, the War of 1812, the Civil War–all had their origins at least in part in disputes over the conditions of international commerce.

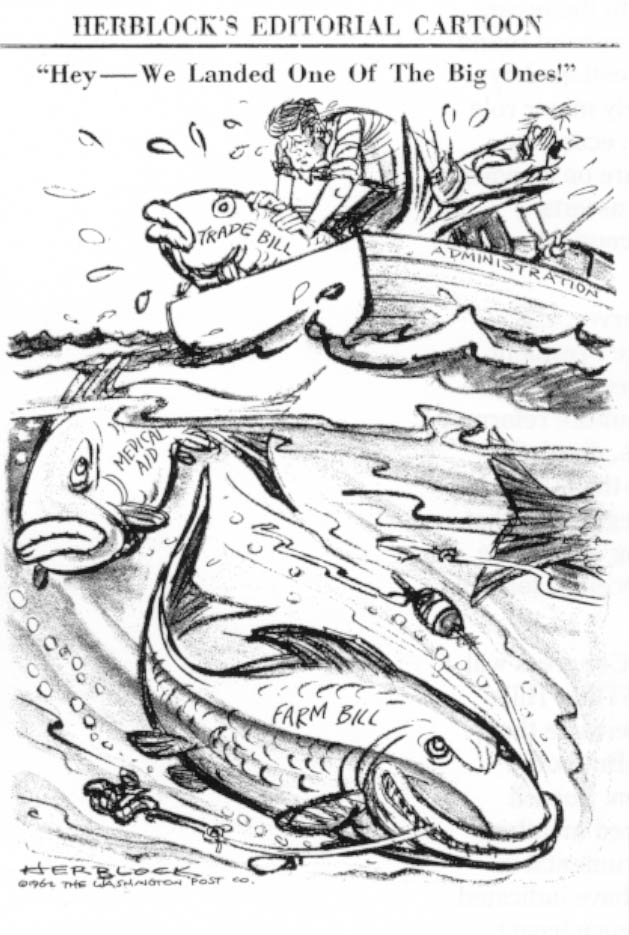

USTR itself is of much more recent birth, arising out of a campaign for a trade bill by President John F. Kennedy in the spring of 1962. The climax of that effort came in the first week of May, when Kennedy flew to New Orleans to deliver a major address at a ceremony marking an expansion of the city’s massive port. As he spoke at the new Nashville Avenue wharf, set on the banks of the Mississippi River, the President discussed the importance of trade in U.S. history, and called on Congress to pass the new trade bill, which would give unprecedented powers to the White House.

America had dominated international trade since World War II, but now there were new challenges to U.S. leadership that required a bold revision of the country’s trading rules. The United States, the President declared, “stands at a crossroads, when it can either shrink from the future and retire into its shell, or can move ahead–asserting its will and its faith in an uncertain sea.”

“We must either trade or fade,” Kennedy warned.

If the rhetoric was overblown, the crowd at the wharf didn’t care. They cheered the President just as an estimated 200,000 people did earlier when his motorcade made its way through the city on that warm, sunny May 4. Kennedy’s audience had no quarrel with his basic message. New Orleans was the nation’s second largest port, and more trade meant more jobs for its citizens. The port area was said by city officials to employ about 50,000 people and account for 75 cents of every dollar spent in New Orleans.

Approval of the Trade Expansion Act was Kennedy’s major legislative goal in 1962. Cuba, civil rights and U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia–issues that we recall as being at the center of national concern that year–had their place, but none, perhaps, had as much sustained White House interest. A “trade expansion bill mystique” was created and an “evangelical” campaign mounted for passage, Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger wrote in his history of the administration.

A few weeks after the New Orleans speech, Kennedy got his trade bill passed by the House, with a comfortable 298 to 125 margin, and Senate approval followed in September. It was one the biggest congressional victories Kennedy enjoyed during his three years in office. But besides giving the President the authority to cut tariffs by 50 percent in upcoming international negotiations in Geneva, the bill contained a major change in the stewardship of the trade talks. For 30 years, the State Department had organized and led trade negotiations. Under the new bill, a special representative appointed by the President would be in charge.

The post was created at the insistence of Rep. Wilbur Mills of Arkansas, the studious, shrewd chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, which oversees trade legislation. The State Department had been under attack for years in Congress for highhandedness and its alleged eagerness to reduce U.S. trade barriers while not requiring sufficient reciprocity from America’s foreign partners . If Kennedy wanted such sweeping tariff-slashing powers, Mills insisted that he reassure Congress by putting trade negotiating authority in the White House, where, because of its political sensitivities, legislators and representatives of American business and agriculture presumably would have influence.

Kennedy’s purposes and those of the State Department were not so far apart, of course. The President’s preoccupation with the bill was not due to any great infatuation with classic economic theory–which holds that the reduction of trade barriers allows more efficient producers to flourish, providing lower prices that benefit more people in the long run. He believed in that (as have most American leaders in the postwar era), but what excited him about the bill was using trade policy to strengthen the U.S.-European alliance against the Soviet Union. In the early 1960s, the members of the recently-formed European Community–France, West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg-were laying the ground rules for their economic union. As part of this effort, they were establishing a common tariff for imports. Kennedy wanted the power to bargain down tariffs significantly on both sides and keep economic disputes to a minimum.

Kennedy also sought the agreement of Western nations to lower their gates to allow in products from poor Third World countries, so they would prosper and be less susceptible to Communist influence. Similar arguments were made by the President in support of opening markets to Japan, whose exports of transistor radios, textiles and other products were not viewed as serious economic competition for the United States.

So the trade bill had a fundamental political purpose. The legislation was something every citizen–”as a patriot concerned about national security, as an American concerned about freedom” should support, Kennedy said in New Orleans. Mills wanted to make sure that U.S. commercial interests would not be sacrificed to the promotion of the administration’s foreign policy goals.

The United States, to be sure, wasn’t facing a trade crisis in the early 1960s. In part because of postwar U.S. promotion of open markets, the country enjoyed an annual trade balance of about $5 billion. American technology–from factory machinery to refrigerators–was in strong demand overseas. American producers of cotton, grains and other agricultural goods made big profits from the exports sales of their enormous surpluses. Kennedy’s trade plan would make it even easier for U.S. companies to sell abroad.

Nevertheless, certain American industries, makers of such disparate products as glass, carpets, and bicycles, faced stiff competition from low-priced foreign goods. U.S. farmers were confronted with the prospects of their exports to the European Community being reduced by its protectionist agriculture policy. “Are we too stupid to realize that everything we’re doing is stultifying our growth?” asked Rep. John Dent, a Pennsylvania Democrat whose district’s coal and glass industries were hurt by low tariff policies. Dent sought a ban on imports that were made by workers whose wage scales were lower than those of U.S. workers. Dent’s proposal didn’t have a chance, but the new trade representative, Kennedy assured Wilbur Mills, would take an “immediate and powerful interest” in the problems of American business.

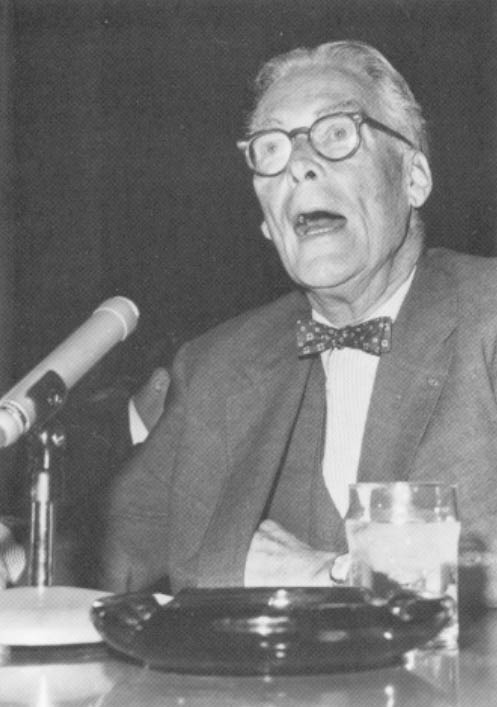

Kennedy’s choice for the first trade representative, former Secretary of State Christian A. Herter, certainly didn’t represent a clean break with State’s dominance of the trade negotiations. And Herter was a fervent believer in the importance of a strong U.S.-European relationship. Born in Paris to expatriate American parents, he had served as a diplomat on the continent following his graduation from Harvard. As a member of Congress in the late 1940s, Herter played an important role in assuring passage of the Marshall Plan to aid European recovery after World War II.

But Herter had some special insights into the conditions of American business and labor that other foreign service officers lacked. The grandfather of his wife, Mary Caroline Pratt, was a Standard Oil partner of John D. Rockefeller (a $100,000 trust fund established by his wife’s father allowed Herter to pursue his interest in diplomacy and politics without financial worry). Herter’s tweeds, bow ties, and towering height give him the air of an aloof patrician, but he was attuned to political realities, having served as a Massachusetts state legislator, congressman and governor. The state’s textile industry had been hit hard by foreign import competition in the 1940s and ‘50s when Herter was in office.

In addition, Herter’s deputies in the trade office were all veterans of the American business world: one as vice president of Ford Motor Company, another as an executive of his family’s San Francisco-based shipping concern, and a third with experience in helping to run an international holding company.

Herter directed the trade talks (which came to be known as the Kennedy Round after the late President) for four long, frustrating years. The Europeans, who were tough bargainers, wouldn’t sacrifice their protectionist agriculture policy, and demanded significant concessions from the United States on other issues. Herter, who wasn’t a particularly assertive personality, found that his close relations with European political leaders weren’t much help in changing their trade policies. The job was also physically taxing. Besides approaching the age of 70, Herter was suffering from severe arthritis and emphysema. He died from a heart attack in December, 1966, only months before the negotiations concluded.

In the end, the United States decided to take what it thought was the best deal possible at the talks, rather than let relations with the Europeans and others founder. Kennedy’s vision of a shining Atlantic Partnership was too optimistic. The accord concluded in June 1967 under the auspices of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) ran into trouble in Congress, which rejected parts of the Kennedy Round. The legislators believed that despite the new organizational structure, U.S. negotiators still “gave away” too much.

After the Kennedy Round was finished, the trade representative’s office fell into dormancy as other agencies vied for supremacy in policymaking. It almost was abolished by Richard Nixon but gained prominence under Robert Strauss, the Texas political dealmaker who served as Jimmy Carter’s trade representative. Yet within a few years, former Senator William Brock, Ronald Reagan’s first appointee to the office, had to battle with the Commerce Department over his agency’s existence.

Each time the trade representative’s power was threatened, Congress stepped in and strengthened or protected the office. The trade representative is now a Cabinet officer, with a significantly larger staff (it numbers about 150, in contrast to Herter’s staff of less than two dozen), including two CIA economists who crunch numbers in a windowless basement room. While in the 1960s it was mainly responsible for tariff cutting, USTR now has responsibility for numerous other activities: working out a complex new GATT arrangement known as the “Uruguay round,” negotiating a free trade agreement with Mexico, arranging a commercial accord with the Soviet Union, and pushing Japan and other nations to remove obstacles to imports. USTR’s negotiators are constantly on the road and inevitably jet-lagged as they try to keep up with disputes over the enormous U.S. trade market, which has shot up in value from a mere $35 billion in 1960 to close to $800 billion today.

Congress’ elevation of USTR has coincided with fears that America is being economically undermined by the hardball trade negotiating tactics and subsidized industries of other countries. Foreign competition was bound to increase as Europe and Japan recovered from the devastation of World War II, and underdeveloped countries began to export more advanced goods.

But with trade deficits regularly exceeding $100 billion, and key high tech sectors taken over by Japan, some legislators say it is time for the United States to abandon its commitment to liberal policies. “We tried to set an example of high-minded ‘free trade’ openness, and we were mugged,” is the way Sen. Ernest Hollings, a South Carolina Democrat, puts it. Underdeveloped countries began to export more advanced goods.

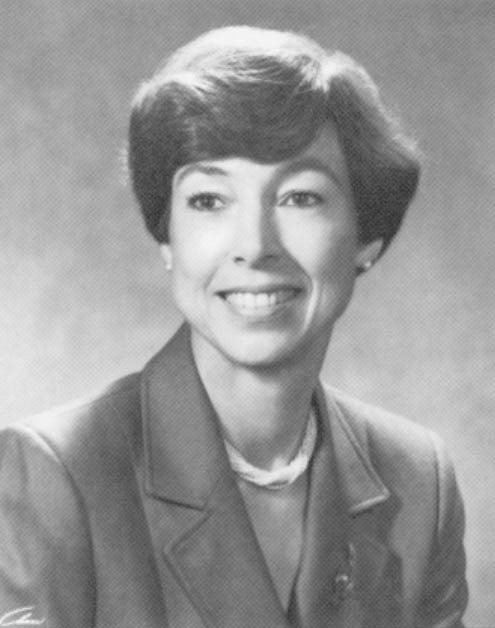

Congress has passed several bills requiring USTR to put “muscle” in America’s trading position, usually by threatening to close U.S. markets in retaliation for barriers abroad. Officials in the agency these days tend to embody that combative spirit. Carla A. Hills, appointed by President Bush as his trade representative, contrasts sharply with the relaxed Herter. A corporate lawyer at the height of her career when she took the job, Hills is an indefatigable worker and stern negotiator. Her attention to details helps to secure commitments from recalcitrant foreign trade ministers, and has won her praise from U.S. companies.

“Carla Hills has really been aggressive for us,” says Harvey Bale, a vice president of the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, a Washington lobbying group. American drug companies make about $25 billion annually in foreign sales, about 45 percent of their total business, and they rely on USTR to help stop patent violations and other actions by foreign firms that reduce U.S. market share overseas.

Robert McNeill, vice chairman of the Emergency Committee for American trade, which represents U.S. multinational corporations in Washington, says of USTR: “I would give them straight As.” The companies McNeill speaks for are pleased with Hills’ pursuit of, among other things, international agreements to open foreign markets to American banks. The provision of financial and other services–as distinguished from sales of manufactured goods–amount to more than S100 billion in U.S. exports annually.

But USTR doesn’t please everyone. It remains a part of the Executive Branch, which means it must seek decisions that are in the national interest, not just what would help one import-beleaguered industry. Indeed, congressional legislation specifies this role, even as it calls for tough action against closed foreign markets. USTR officials spend a good deal of time brokering among government agencies with competing interests in order to come up with a recommendation for the President. The consensus that USTR works out sometimes leaves business and labor unhappy: over the past months, for example, decisions have been made to soften a program controlling steel imports, and oppose greater quotas on foreign textile products.

One Washington lobbyist for a number of U.S. companies, who asked not to be named, says of USTR’s decisions: “The primary motivation is cold and bloodless,” doing what is possible within the administration, “without considering the impact on the U.S. economy, or even understanding the impact on the U.S. economy.”

Although the interests of this lobbyist’s clients have not been ignored, he thinks the current USTR team has little awareness of the nature of its job: to balance competing interests in a way that will ultimately benefit America.

Michael B. Smith, a former deputy trade representative, maintains that the desire not to offend U.S. allies continues to dominate trade decisions. He cites the Administration’s refusal to take action against Japan in several disputes last year as a case in point.

“Trade is still a handmaiden to foreign policy,” Smith says. “The longer we keep this up, the worse it will be for the United States.”

Another complaint, voiced by a lobbyist who handles American and foreign firms, is that USTR has not articulated a clear statement of U.S. trade goals, except to continue “by rote” along the liberal policy path of previous Administrations.

Hills has pursued these liberal trade objectives even when they threaten other deals. She has refused to accept anything less than an agreement by European Community to dismantle its farm subsidies. This stand, which led to the breakdown last December of the current round of GATT talks, has been questioned by some, who note the relatively minor role agriculture plays in the U.S. economy. “You cannot place agriculture on a pedestal above the other issues,” asserts Harvey Bale of the pharmaceutical association.

Another trade policy observer, U.S. Chamber of Commerce Vice President William Archey, says he doesn’t disagree with Hills’ position on agriculture reform. But he warns that Congress, dissatisfied with the lack of progress in the GATT, is getting ready to pass new legislation that would push USTR into using even more assertive tactics against perceived foreign trade sinners.

If the past is any pattern, Congress will do so without criticizing USTR or Hills directly, so as to not to undermine the trade negotiators’ position. But both Wilbur Mills and former Sen. Russell Long of Louisiana, two retired members of Congress who were instrumental in the development of USTR, have indicated disappointment that the agency hasn’t done more to improve America’s trade position.

Current members of Congress, however, have been critical of former USTR officials for their habit of becoming lobbyists for foreign companies. Since 1974, almost half of the senior USTR officials who left the agency, or their firms, registered as foreign agents with the Justice Department, according to a study by the Center for Public Integrity, a Washington research group. Among the most militant trade hawks in the capital, there is a tone of innuendo over the fact that Hills, and her two top deputies, Julius Katz, a trade policy specialist and former State Department negotiator, and Linn Williams, an international business lawyer, did some work for foreign companies before coming to USTR. Such patterns of employment may keep USTR from being demanding enough in trade negotiations, these critics say.

But even those who exclusively represent American companies in Washington see little evidence that former USTR officials have been able to tilt the decision-making process in favor of foreign firms, “It’s occasionally troubling,” says Alan William Wolff, an attorney for U.S. semiconductor and steel companies. “I never saw it as much of an issue.”

While a persistent negotiator, Hills shies away from the “trade warrior” mantle. She says her agency’s chief job is to coordinate trade policy, and points to the Commerce Department as the primary advocate of U.S. business interests.

Congress, however, deliberately did not shift trade negotiating authority from State to Commerce in 1962 because it was felt that Commerce was too big and clumsy to do that job well. Efforts since then to convert Commerce into a “Department of Trade and Industry” have been resisted by the legislators for the same reason. Hills’ reluctance to fully embrace the warrior role reflects the difficulty of being both advocate and coordinator. “They are at war with each other,” admits one of her top aides. “It’s very hard to be both.”

Hills’ dilemma also raises the questions of what America’s international economic interests really are, and how to best promote them. For the workers at the port of New Orleans, increased imports are welcome, even if they may displace products made in Ohio. Who should the U.S. government favor? Even more perplexing is the question of whether USTR should be giving priority to breaking down barriers abroad to products made by U.S. companies at their overseas factories. At the moment, American policy is to do so, but some argue that the export of domestically-made goods should receive greater help.

More fundamentally, the disagreements over trade policy reflect differing views over the role of government in the economy. Hills and her Bush Administration colleagues reject the notion that government should intervene to help troubled industries with cash and management. Similarly, the administration doesn’t approve of making arrangements with foreign governments to regulate the flow of goods in strategic industrial sectors (although both Bush and previous Presidents have occasionally done that).

Hills and other U.S. trade officials say they hope that America’s competitors can be convinced to see the benefits of a liberal trade philosophy. But foreign governments continue to back their companies with subsidies, allow anti-competitive cartels to flourish, and protect their markets from imports. Hills and her agency have not yet been able to devise a strategy to effectively counter that challenge.

©1991 Steven J. Dryden

Steven J. Dryden, a Maryland freelance writer, is investigating the origins and accomplishments of the office of the U.S. Trade Representative.