George Prill liked to work on a large scale. As president of Lockheed’s international aircraft unit, he tried to make an unprecedented deal for the sale and production of L1011 jetliners with the Soviet Union in the mid-1970s. Later in the decade, he played a major role when Lockheed began building a $2 billion airbase for the Shah of Iran. That both ventures eventually crumbled convinced some colleagues that Prill, a stylish dresser with red hair, was too much of a gambler. To his admirers, the failures were just part of what insiders call the “sporty game” of risk-taking in the global aerospace market.

In the spring of 1978, Prill launched another big project. American diplomats were in the fifth year of international trade negotiations known as the Tokyo Round after the city in which they began. Prill and other aircraft company executives feared the negotiations might not help their companies. For Lockheed, Boeing and McDonnell Douglas – the Big Three of American commercial aviation at the time – the chief threat was Airbus Industrie, a multinational European consortium that also made civilian jets. The Airbus planes were more fuel efficient than American ones, and had large seating capacities, which was just what airline companies wanted after the cost of oil soared in the Seventies. But Airbus had another great advantage–massive government subsidies that allowed the company to break into the market by offering cut-rate prices.

American companies enjoyed much less direct government support. Prill wanted the office of the Special Trade Representative (STR), the U.S. government’s trade negotiating agency, to reach a deal with European countries to limit the use of government aid in aircraft manufacturing. “It was clear that if they (the Europeans) weren’t constrained, they’d knock the hell out of us,” Prill says.

The negotiation of an international trade agreement covering a specific industry had never been done before, and some STR officials were opposed to the idea. But Prill was undeterred. After uniting the U.S. industry behind his plan, he approached European aircraft makers and governments, offering the elimination of U.S. tariffs on aircraft, engines and components in exchange for a subsidy-limiting deal. Prill recalls that he was frank with the Europeans, warning them that “either you play fair” or “we’d flex our muscles and do everything we can to hurt you.”

STR officials, outraged by Prill’s behavior, threatened him with prosecution because they thought he was representing himself to the Europeans as a U.S. government official. But by July he had convinced Robert Strauss, the Texas Democrat who was the trade representative at the time, to back his plan for the aircraft negotiations. (For Strauss, acceding to the aircraft companies’ wishes was one way of building political support for congressional approval of the Tokyo Round results).

An aircraft agreement was concluded in April 1979 in the final days of the Tokyo Round, which was held under the auspices of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the body that sets world trade rules. “Our objective,” said Stephen Piper, the STR negotiator of the aircraft accord, in testimony before Congress later that year, “was to provide a comprehensive basis for free and fair trade in the civil aircraft sector. The Agreement does that.”

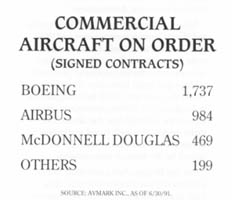

But 12 years later, the subsidy issue still divides Europe and the United States. The Airbus consortium, which now has a whole “family” of commercial planes built with an estimated $13 billion in government aid since 1970, is the world’s number two supplier. McDonnell Douglas is third, and continues to lose market share to Airbus (Lockheed, wounded more by costly management mistakes than competition with Airbus, has dropped out of the commercial jet business).

Boeing remains the supreme manufacturer, but is fearful of Airbus’s growing strength. For the United States, which had a $23 billion trade surplus in the aircraft sector last year, Airbus challenges one of the country’s few areas of leadership in high technology. Negotiations have failed to resolve the subsidy issue and there are predictions of a trade war.

“We are headed for a crisis with Europe over subsidies paid to Airbus,” warns Linn Williams, a former deputy U.S. trade representative who headed negotiations on the issue.

How did this happen? An examination of the history of the Airbus dispute reveals three fundamental problems: the original aircraft agreement was deeply flawed; American manufacturers have given conflicting advice to the U.S. government; and the government itself has been divided over what tactics to use.

International trade agreements are notorious for their elliptical style, and the aircraft accord’s section on subsidies is an especially fine piece of artful ambiguity. It says, for example, that signatory governments, in their support of aircraft programs, “shall seek to avoid adverse effects on trade in civil aircraft.”

The signatories are also, when considering the extent to which governments should back aircraft programs, to “take into account” the existing “widespread government support in this area.”

U.S. government officials now refer to these and other clauses as the “weasel words,” but for the Europeans, the words legitimize the Airbus program. “None of this was accidental,” says a British official who was involved in the negotiation of the aircraft agreement. “The language can have these different interpretations put on it, and everyone knew that at the time.”

The usefulness of the aircraft agreement is further undermined by that fact that, like all GATT accords, it has no enforcement mechanism. It is up to GATT members to find a way to bring an offending signatory into line.

Prill says he was under no illusions in 1979 that the aircraft agreement would solve all the industry’s trade problems. Nevertheless, he says, “I thought we’d made a major step.” The government’s advisory group of aviation industry executives, chaired by Prill, also endorsed the agreement.

In the early 1980s, as the Airbus consortium continued to pick up major orders from airlines around the world, the planes were a source of pride for Europe. Many industries there were suffering from what commentators derided as a “sclerosis” of slow growth and technological backwardness, and were falling further behind their American and Japanese rivals. Airbus was an exception to this pattern, and in addition, it appeared to vindicate the European view that government has a explicit role to play in national economic development.

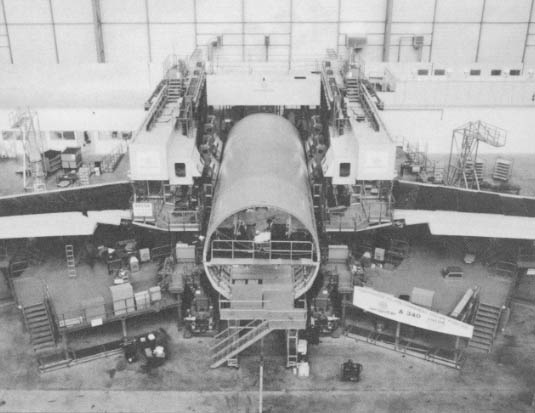

Airbus was created in 1969 by the French and West German governments and their state-run aircraft manufacturers as a deliberate attempt to challenge the dominance of American commercial aircraft producers (Britain and Spain have since then also joined the program). With its headquarters in Toulouse, the Airbus consortium operates under a French law that allows it to make design, production and marketing decisions, but its financial risks are assumed by the sponsor governments.

For the Reagan Administration, which professed a free market doctrine, this kind of government activism was heresy. So in 1985, when the administration was under pressure from Congress and business to do something about the soaring trade deficit, it chose Airbus as an example of what it called “unfair” foreign trade practices. The Airbus consortium had just launched a new model, the 150-seat, twin engine A320, backed by more than $2 billion in government aid. U.S. manufacturers were unhappy with the financial assistance their rival enjoyed, as well as alleged pressure put on European airlines by their governments to buy the Airbus.

At that point, however, only the renamed Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) and the Commerce Department were seriously concerned about Airbus. When a Cabinet-level “strike force” committee met in the White House Roosevelt Room in 1985 to consider the issue, Secretary of State George Shultz said the Airbus dispute was a “nonstarter,” according to then-Deputy Trade Representative Michael Smith, a participant in the meeting. Shultz, whose chief concern was maintaining good U.S.-European political relations, dismissed the idea of contesting Airbus, saying, “This is an attack on European manhood,” Smith recalls. Bruce Stuart, the Commerce undersecretary for trade policy at that time, remembers the normally placid Shultz as “concerned, verging on being upset.”

In the months that followed, other Cabinet agencies raised objections. The Transportation Department, reflecting the views of American airline companies, thought it was good to have Airbus competing with U.S. manufacturers because it meant planes would cost less. The justice Department was worried that USTR would negotiate with Airbus on the pricing of planes, thus illegally restraining competition. Members of the White House Council of Economic Advisers belittled U.S. industry complaints.

Throughout the rest of 1985 and 1986, the most vigorous action the United States took was to hold informal negotiations with the Europeans. The talks produced very little except haggling over the GATT agreement. To American claims that Airbus received forbidden subsidies, the Europeans countered that U.S. aircraft manufacturers benefited from the massive government financial support poured into research and development for these companies’ military projects.

(Not so, replied U.S. officials, since the connection between military and commercial aerospace production has become much less important over time. Furthermore, European aircraft companies are themselves the recipients of big government defense contracts.)

Airbus officials also ridiculed U.S. complaints about a “threat” to the American aircraft industry. “Our critics,” notes Airbus Industrie President Jean Pierson, say government support “is unfair trading since it causes distortion in trade. Let me ask this question: would not the distortion be greater if Boeing and Douglas had 100 percent of the market?”

By the end of 1986, McDonnell Douglas was becoming increasingly worried about the launch of a new Airbus jetliner program, the A330/340, because the plane would compete directly with the company’s planned widebody MD11. McDonnell Douglas Chairman Sanford N. McDonnell began pressing the administration to take a tougher stance on Airbus.

In January, USTR’s Michael Smith and Commerce Undersecretary Bruce Smart flew to Europe and held a series of acrimonious meetings with officials over the Airbus subsidies. The Europeans responded indignantly to the high-profile attack on their prized technological success story. French Prime Minister Jacques Chirac charged the United States with economic “hostage taking” and “aggression,” and vowed counter-retaliation if the United States used trade sanctions against Europe, according to news reports.

After Smith and Smart returned, they put together a Cabinet coalition to back a plan that could have led to sanctions against Europe. But on the morning of February 13, just hours before the Cabinet was to meet, Sanford McDonnell called several Cabinet members and told them to tone down their action. In the preceding several weeks, McDonnell Douglas executives had been warned by the government-controlled European airlines that they wouldn’t buy Douglas jets if the United States staged a confrontation over Airbus.

The Cabinet followed McDonnell’s directions, but USTR and Commerce officials were angered by the turnaround, feeling they had been made to appear foolish in front of their Administration colleagues. Boeing Chairman Frank Shrontz, who wanted a tougher approach, was also upset by McDonnell’s action. “I’ve never seen Frank Shrontz so disgusted,” says an attorney involved in the Airbus case.

McDonnell Douglas has tried to play down the incident. One aircraft industry executive says, “There’s no big deal here.” What McDonnell Douglas was doing, he says, was using the government to turn up the pressure on Airbus, then backing away when it became too dangerous. “Everything is force and counter-force,” the executive comments, describing what he sees as the realities of the business world.

But the McDonnell Douglas episode left trade officials distrustful of the aircraft companies. It also made the Europeans doubt U.S. resolve, according to Alan Boyd, chairman of Airbus’s North American operations. McDonnell Douglas further clouded the waters by pursuing, on-again, off-again talks with Airbus about a limited joint production agreement that would allow the two companies to compete better against Boeing. Confusing the picture even more, General Electric, which manufactures engines for both American and Airbus jets, has lobbied against U.S. sanctions.

Yet Boeing and McDonnell Douglas–acting like guerrilla armies with a talk-and-fight strategy–continue their vehement criticisms of the Airbus finances. The complaints grow stronger when the companies have completed a major round of selling that leaves them less vulnerable to retaliation by European airline buyers.

The U.S. government in recent years has become more united on the Airbus issue in response to Europe’s continued use of state money to back up Airbus. In late 1988, the West German government committed more than $2 billion for the privatization of Deutsche Airbus, the German partner in the consortium, by the Daimler-Benz company. The money is to be used to protect Daimler-Benz against fluctuations in the dollar/mark exchange rate that could result in less revenue for Airbus.

Trade Representative Clayton Yeutter thought that in 1987 he had secured the West German government’s agreement against the use of such exchange rate guarantees. In an unusually blunt statement issued after the West German action, he said it was “indefensible,” and “inconsistent” with the country’s free enterprise system.

Yeutter made these comments, however, just as George Bush was elected president. Yeutter moved on to be Agriculture Secretary. His scrappy deputy, Michael Smith–who became so engrossed with the Airbus issue that he began hanging model airliners from his office ceiling–left the government to become a trade consultant.

In a sense, the game started all over again, and it took the current trade representative, Carla Hills, and her team two years to build up the level of frustration felt by Yeutter and his aides. After an American proposal was rejected by the Europeans in February, Deputy Trade Representative Williams urged the administration to seek a ruling by a GATT panel of experts on the Airbus case. This move could lead to American retaliatory tariffs placed on European products, followed by European counter-retaliation against U.S. imports. The trade war will “shed lots of blood without reaching the objective,” says one U.S. trade official who negotiated the issue, because the Europeans will never give up their right to subsidize. “There will be lots of damage (done) to innocent bystanders,” he predicts.

A French trade official came to Washington in mid-April for further talks, but Williams, normally a patient and soft-spoken man, couldn’t hide his weariness and annoyance. When the official warned that French President Francois Mitterrand would intervene with Bush to stop the United States from going to GATT, Williams responded by writing the White House telephone number on a piece of paper and laying it on the table. Mitterrand apparently did not call. On May 9, a government committee chaired by Williams voted unanimously to ask for the GATT ruling.

But at the rate Airbus is acquiring market share, it probably will not matter even if the Europeans eventually agree to reduce Airbus subsidies. Says George Prill: “You can’t stop the thing now.”

Some have taken a lesson from the Airbus affair, urging the U.S. government and American industries to be much more careful about approving trade agreements that are so obviously weak and unenforceable, and spend more time strengthening the country’s economic base.

“Over the years, a culture has developed to reach a (trade) agreement, and pay a lot to reach that agreement,” says Robert Robeson, a vice president of the Aerospace Industries Association, a Washington lobbying group. “The days when we could do that are long gone. It is better to walk away from the table than to reach a bad agreement.”

©1991 Steven J. Dryden

Steven Dryden, a Maryland writer, is examining the U.S. Office of Trade Representative and international trade issues.