When Deputy U.S. Trade Representative Linn Williams entered the White House Cabinet Room late in May of 1991, he was feeling both exhilarated and apprehensive. Just a few days earlier, he had completed months of delicate negotiations renewing the U.S.-Japanese agreement governing trade in semiconductors, the tiny bits of silicon circuitry that are the foundation of advanced electronics. Trade in semiconductor “chips” is one of the sorest points in U.S.-Japanese relations, fraught with charges by American companies that Japan has used predatory tactics to weaken a crucial high technology industry.

Others believed Japanese intentions were less threatening. They didn’t think the U.S. government was properly set up to save the U.S. semiconductor industry, nor could any government efficiently carry out such an effort. Within the White House, powerful figures such as then-chief of staff John Sununu and budget director Richard Darman held to this view.

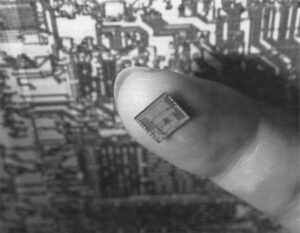

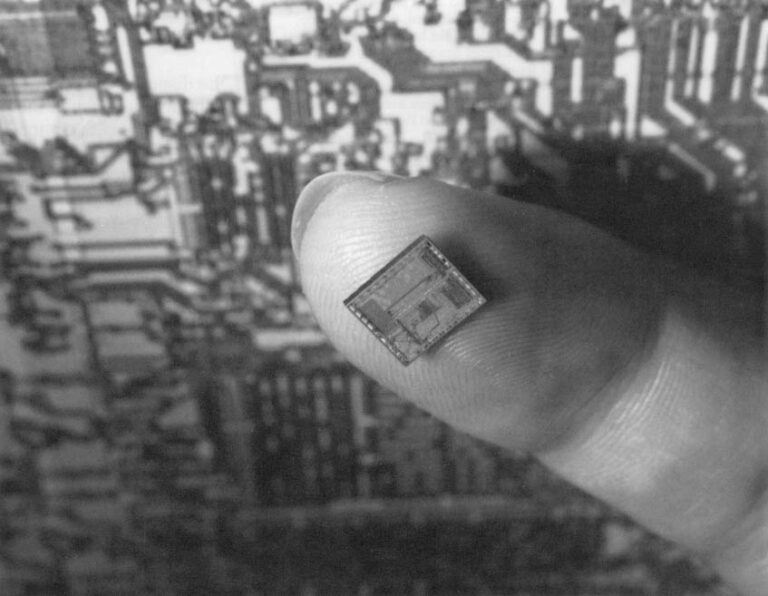

Undisputed is the fact that chipmaking brings in $50 billion in annual global sales, a sum that is expected to grow to more than $75 billion by the middle of this decade. Such revenue could go a long way to boost the prosperity of any country that dominates the semiconductor market.

Williams, a slight, greying man in his mid-40s, had removed most of what the opponents didn’t like in the original U.S.-Japanese accord, and he had carefully obtained the backing of a majority of the Cabinet departments. But as he listened to President Bush run through the agenda at the Cabinet meeting, Williams worried that Sununu and Darman still might have primed Bush to object to the new agreement. The President’s instincts were to steer away from active government involvement in the economy.

To Williams’ relief, the Cabinet meeting ended without Bush bringing up the chip accord. “I was waiting for the other shoe to drop, but it didn’t,” Williams recalls.

On June 11, Williams’ boss, Trade Representative Carla Hills, signed the new agreement with Japanese Ambassador Ryohei Murata. Hills said the arrangement was “in keeping with President Bush’s continuing commitment to reduce government intervention in international markets and promote free trade.”

The semiconductor agreement is nevertheless the most explicit trade accord in existence between the United States and Japan. Some specialists believe it sets the pattern for the future, management of sensitive international commercial issues. “Trade frictions in semiconductors are just the beginning of what promises to be a massive tangle of trade disputes in other high technology sectors,” predicts Kenneth Flamm, an economist and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, a Washington D.C. think-tank.

The United States and Japan, as important producers of computers, telecommunications equipment, satellites, pharmaceuticals and other advanced goods, must define the rules for governmental intervention and corporate collusion in these areas, or face greater clashes ahead, Flamm believes. How these issues are resolved, he suggests, “will shape the world trading system for years to come.”

The terms of the 1991 semiconductor agreement indicate that, for the time being at least, the United States will keep its distance from the explicit management of trade in high-technology products. While the government has extended some assistance to the chip industry to help it better compete against Japan, American companies are basically on their own.

The dispute over semiconductors began in the 1960s when the U.S. companies that first developed the devices attempted to expand their operations in Japan.

When Fairchild, Texas Instruments, and other American firms started pushing to enter the Japanese market, the Japanese had no comparable products but were determined to catch up. The government used quotas, tariffs and severe investment restrictions to keep American companies at bay. (If the companies wanted to establish facilities in Japan, they were required to share know-how with Japanese electronics firms.) Despite these barriers, which were forbidden by international trade rules, U.S. manufacturers captured more than one-third of the Japanese semiconductor market by the early 1970s.

William Eberle, a former Idaho businessman and politician who served as trade representative in that period, badgered the Japanese to speed up the dismantling of their formal trade barriers in the semiconductor sector, which finally took place in 1975. At that point, however, the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), which had been sponsoring programs to upgrade the country’s semiconductor production capabilities, stepped in and began discouraging Japanese companies from buying American chips. The government also poured more money into the development of semiconductor manufacturing technology. “Japanese chip makers would henceforth have a head start toward cost and quality leadership,” Brookings’ Flamm observed in a study of the issue.

In the early 1980s, the Japanese use of aggressive price discounting for chips led American companies to charge that U.S. trade laws against “dumping”-selling below the cost of production-were being violated. The American companies, as they pressed the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) to take action against the Japanese, also complained about their rapidly declining share of the Japanese domestic market, which by that point stood at about 10 percent.

Japanese strength was bolstered by the fact that its semiconductor manufacturers were part of huge, diversified companies that could absorb losses resulting from market downturns. Most American chip firms were, by contrast, smaller and more exposed to financial pressure.

In addition, the Japanese began beating their American competitors in meeting quality standards. Although by the mid-1980s the U.S. firms pulled even again with Japanese in quality, the Japanese by then had a virtual worldwide monopoly in one major category of chips, known as DRAMs, which store information inside computers. The Japanese pressure, combined with a severe slump in demand, caused most American companies to withdraw from DRAM production. Faced with serious Japanese competition in other semiconductor categories, U.S. chip firms formally petitioned the Reagan Administration for help, which they believed had to include a commitment by Japan that American companies would be guaranteed a percentage of the Japanese market.

The Commerce Department was already convinced something had to be done. But Clayton Yeutter, Reagan’s trade representative, was undecided, particularly as to pushing the Japanese for a market share guarantee. It went against his free trade instincts.

Leading the efforts in Washington of the Semiconductor Industry Association, the chipmakers’ lobbying group, was Alan W. Wolff, a lawyer and former deputy trade representative under President Jimmy Carter. Wolff, a soft-spoken Massachusetts native and Columbia Law School graduate, believes that given the proper information, government will respond. For the semiconductor case, he unloaded a bound volume of several hundred pages of translations from the Japanese press showing how the Japanese government had protected and promoted its chip industry.

Working for the Japanese semiconductor companies in opposition to a trade action was another former deputy trade representative, attorney William N. Walker, who had known Yeutter in the 1970s when they had both served in the trade office. Walker lobbied Yeutter persistently, but so did Wolff, another 1970s USTR alumnus. With Congress pressing heavily for “toughness” with Japan, and the U.S. semiconductor industry in a virtual free fall, Yeutter ended up championing industry’s position, including the negotiation of a market share arrangement. “He became a convert,” Wolff recalls proudly.

The five-year agreement concluded with the Japanese in the summer of 1986 required the Japanese to end the dumping of chips in the United States and other countries, and contained a commitment by the Japanese government to support the growth of U.S. market share in Japan to 20 percent. (This latter section was only contained in a side letter to the agreement, kept secret at the insistence of Tokyo.) But it took the imposition in 1987 of retaliatory tariffs on Japanese imports of electronic gear-the first such trade action against Japan since World War II-to insure the end of Japanese dumping of chips.

In 1989, when Carla Hills and Linn Williams began to consider what to do about the renewal of the semiconductor agreement, most of the chip industry argued that the pressure on Japan should be maintained or intensified. But American companies that made computers and other products that depended on semiconductors were opposed.These companies charged that the 1986 accord, by requiring the Japanese government to supervise its chip producers, created in effect a cartel that could maintain or raise prices at will. American companies were convinced that this is was what happened in the late 1980s when, despite a drop in demand, prices stuck.

Alan Wolff and his colleagues working with semiconductor association don’t see it that way. They have evidence that the Japanese companies were collaborating before the 1986 agreement. But SIA couldn’t convince the chip users, so it began talks with the representatives of American computer makers to see if they could reach common ground on the renewal of the chip accord. The result was a joint position in late 1990 that endorsed less stringent monitoring by the Japanese government of the country’s semiconductor companies, while maintaining the 20 percent market goal.

It was a position that Williams and Hills welcomed. Hills had been warned explicitly by John Sununu that the White House was not in favor of renewal of the old accord. Williams personally didn’t think much of “managing” trade, but he did believe the United States had to show some consistency in its policies, and just couldn’t drop the 1986 agreement. Having worked in Tokyo as a lawyer for an American firm, Williams-whose office was filled with Oriental artwork and knickknacks-saw the renewal as a challenge to find a constructive way to bridge an explosive trade issue.

Williams picked two agencies, Commerce and the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) as the keys to securing U.S. government approval of a renewal. Commerce, which is close to business, represented one end of the spectrum, while CEA, which reflects an anti-interventionist outlook, was the other. Williams had an inside track to the tiny CEA because he had known one of its three members, John Taylor, since college.

Both the Japanese and the CEA were opposed to the idea of maintaining the 20 percent market share goal in the agreement. So Williams developed the idea of a market “access” objective, of which a strict market share, percentage would just be one aspect. Other methods of measuring access would be the extent to which Japanese electronic companies establish relationships with foreign semiconductor companies and take steps to regularly use chips made abroad. The new arrangement also specified that the two governments expected the foreign share of Japan’s semiconductor market to exceed 20 percent by the end of 1992. The association was happy to finally get that out in the open.

With Commerce and the CEA both on board, Williams was able to get the approval of the -governmental committee that recommends trade policy to the Cabinet. When Bush gave the new agreement his tacit go-ahead at the meeting last May, he was no doubt exercising his well-known instinct for the pragmatic option. In addition to the Cabinet supporters, there were enough powerful members of Congress and industry executives to create political problems for the President if he dismantled the agreement completely.

What did the first semiconductor accord do for American companies? Their decline seems to have been arrested, although analysts disagree on whether U.S. chipmakers have held their own in the global market, or are inching forward. In the United States, domestic companies have a healthy presence in several chip categories, but the firms have not reentered DRAM production.

The Japanese market remains the biggest battleground. Chip sales there totaled almost $19.6 billion in 1990, compared to 14.4 billion in the United States. The U.S. share in Japan grew from less than nine percent in 1986 to more than 13 percent in 1990, a modest improvement that executives of several chip companies say was due in part to the Japanese government’s prodding of their firms to buy American products.

But as the U.S. government moves away from its experiment in managed trade, the semiconductor industry will have to rely for the most part on its own initiatives. These are well underway, in fact. Cooperative ventures between Japanese and American companies – in which cash, information, technology and training flow back and forth- have proliferated in recent years. Some critics see it as a sign of American desperation for Japanese money, but there are signs that U.S. firms are extracting benefits too. No longer is American know-how preeminent, and if U.S. companies really want to sell in Japan, they’ve got to become better acquainted with the calculations of buyers there. The 1991 chip agreement is designed to encourage these cooperative deals, building on the call for market share contained in the original arrangement.

One senior executive of a major American electronics firm praises Williams for the way he renegotiated the chip arrangement. “I believe that without his positive inclination, it would have been difficult to get the renewal,” he says. “He (Williams) understood the Japanese better than anyone.” Yet this executive remains pessimistic about the future of the U.S. semiconductor sector, given the huge financial resources of Japanese manufacturers. “They will out-invest us,” he predicts.

But William Finan, a Washington consultant and former Commerce Department high technology official, sees hope in the improved ability of the U.S. chip industry to coordinate its research and development activities. Greater amounts of R&D funding have emerged, and the congressionally-sponsored Sematech organization, which is focused on improving chipmaking technology, is beginning to show results, he points out.

“Given the fact that you have an Administration that is inherently hostile (to an activist role in the economy), this is movement forward,” Finan says. “It’s a question of whether you can get these programs to take hold.”

For the foreseeable future. it may be impossible for either Japanese or American companies to dominate the chip market. Strategic alliances will probably continue to be the order of the day, since even the Japanese are hesitant to go it alone and put up the $500 million or so it takes to back a new semiconductor design.

©1992 Steven J Dryden

Steven J. Dryden, a Maryland freelance writer, is examining the role of the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative in foreign trade.