McGeorge Bundy hardly guessed how long a journey he was beginning when he traveled to Philadelphia in August 1966 to address the annual banquet of the National Urban League. After drinks and dinner in the formal hotel ballroom, the new president of the Ford Foundation spoke for half an hour or so about what he called the problems of “the American Negro.” His well-dressed, integrated audience must have found it all a little bewildering. After all, as Bundy himself admitted, he had virtually no experience in the realm of race relations. Fresh from five years in the White House, where he had worked 12-hour days as special assistant for national security, Bundy had been so busy with Vietnam and other problems that he had scarcely had time to read newspaper accounts of the civil rights movement.

Nor had Ford, or any other large foundation, shown much interest till then in the plight of blacks: it was considered just too big a problem, and too controversial. Yet here was Bundy, with one sweep of his hand, committing the nation’s largest foundation to an all-out attack. “We believe,” he said, “that full equality for all American Negroes is now the most urgent domestic concern of the country.”

The audience could see that Bundy had done a little homework; he even told them about one of the books he had read. He duly noted what everyone knew: that the civil rights movement had recently entered a new phase, moving beyond the fight for legal rights, on to the harder battle for real, concrete equality. And he tried to show that he was up-to-date by touching briefly on Black Power-although when he mentioned it, he looked up from his text and admitted that he didn’t “understand” it.

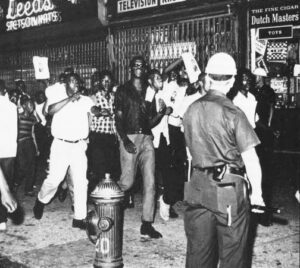

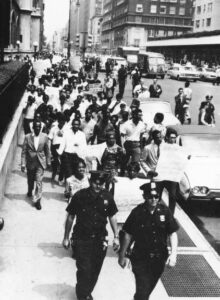

His middle-class listeners weren’t sure they understood it either. The slogan had been born only two months earlier, in an angry speech by new SNCC chairman Stokely Carmichael. No one knew exactly what he meant–whether he was calling for violence and black supremacy or merely, as he claimed, black pride and electoral power. But the civil rights movement had already split bitterly over the issue, and as a third summer of rioting wracked city after city, both blacks and whites knew that race relations were spinning out of control. Against that background, Bundy’s speech was all the more important: after all, if anything could help the cities, perhaps the Ford Foundation’s millions could. But the growing chaos in the streets also made the speech sound just a little hollow. Eloquent and earnest as Bundy was, sure that “America remain [ed] the home of hope,” many in his audience couldn’t help wondering whether he knew what he was taking on.

As it turned out, a good part of Bundy’s 13 years at Ford was indeed devoted to the race problem. Like much of America’s liberal establishment, he had come to see racial issues as the nation’s top priority–and, like most of his contemporaries, he believed implicitly that institutions like Ford (along with the federal government) had it in their power to ameliorate such problems. Bundy’s years at Ford did not prove him entirely wrong, but nor did they bear out the crusading optimism that drove him forward in 1966. In this, the story of what he did at Ford–his hopes, his achievements, his blunders and his deepening sense of difficulty–is a key chapter in American race relations. Bundy represented the establishment’s best effort to grapple with the problem by making good on the promises of the civil rights era. The results of that effort were mixed at best–but the lessons learned then are as apt as ever today as Americans begin again to look with urgency for some solutions to the problems of race.

None of the challenges that Bundy faced at Ford were to prove more difficult than the matter he touched on so briefly and diffidently in that first speech–the matter of Black Power. Bundy was to become deeply entangled with Black Power–and the questions this raised were to haunt him until the end. His critics, mostly on the right, remained at a loss to understand how this patrician intellectual and Vietnam “hawk” could have carried the Ford Foundation–in itself an arm of the American establishment–into even a fleeting embrace of the Black Power movement. How could Bundy, of all people, have put the resources of his powerful institution behind the idea of black separatism? Did he not grasp the danger of spiraling race-based bitterness? And did he not see how he was helping to sanction the nation’s turn away from the ideal of racial integration? The answer, in part, is about misplaced good intentions. But that does not fully explain what went awry.

McGeorge Bundy attacked the race issue with the same vigor and confidence that he brought to everything he did. In part, it was the confidence of his class and background. Born into the heart of old New England privilege, a product of Beacon Hill, Groton and Yale, Bundy had grown up among men who naturally assumed that they would lead the nation-and, most likely, lead it to reshape the world. Among his mentors were close family friends Henry Stimson and Dean Acheson, the two primary architects of America’s twentieth-century effort to build a global order. (As a young man, Bundy co-authored Stimson’s memoirs and edited a book of Acheson’s speeches.) Bundy grew up with all of these men’s activist assumptions, and with the added certainty that comes with rare intelligence. A legendary student, formidable debater and dazzling young college professor, Bundy was named dean of Harvard College at the precocious age of 34. Six years later, he was called to the Kennedy White House, in itself as vigorously confident an administration as any that had ruled the country in decades.

Bundy was the brightest of the bright young men around the glamorous President, and his cool, decisive manner soon came to epitomize the Kennedy style. His unassuming title belied his power. (So did his deceptively boyish looks: slender build, sandy hair, noticeably pink cheeks.) On arriving in Washington, he skillfully reshaped the national security assistant’s job, making it the power base that it remains today: as the President’s traffic cop and agenda-setter, Bundy quietly guided foreign-policy-making from the White House basement. What he lacked in institutional heft, he again made up in sheer brain power. Kennedy’s ultimate compliment, in the eyes of one reporter, was his exasperated remark one evening that he and Bundy and had been arguing all day: only the quick-witted and confident security assistant could engage the President that long.

Like Bundy himself, the Kennedy administration was sure that it could solve any problem–whether putting a man on the moon or bringing democracy to southeast Asia–through rational analysis and the deft use of money or force. It was an activist, interventionist government, yet one that saw itself as working toward an almost non-ideological vision of human betterment. Like the President, Bundy was politically unclassifiable–neither a liberal exactly nor a conservative. (As a Republican in a Democratic White House, he effectively had no party either.) What’s more, for all his influence, he left no particular stamp on American foreign policy. But neither he nor anyone else seemed to see this as a failing: on the contrary, he was most lauded for his hard-headed pragmatism-that tough, austere analytic mind unencumbered by ideology or emotion.

By the time he left the White House, in early 1966, America had begun to have doubts about the Kennedy (and Johnson) credo that government could “do anything.” Vietnam was only the most obvious failure. The developing world was as unruly as ever, the War on Poverty had not come to much, and Americans of all colors and classes were losing faith in the power of ideals. Yet if Mac Bundy shared these doubts, he did not show it. On the contrary, by all accounts, he seemed to see the Ford Foundation as the just the right vehicle to carry on the work–to forge ahead with fashioning a more perfect world. “The idea,” he said during his first months, “is to do things society is going to want after it has them.” He and the foundation “were eager for new ideas,” he said, keen “to move into the hot firing lines.” And so it was, almost in spite of himself, that McGeorge Bundy found himself slipping into political activism.

Bundy launched the program with characteristic energy and dispatch. The very month he arrived in New York, he secured the board’s formal blessing to make race the top priority. Then he got down to studying the issue in earnest. He read everything he could get his hands on and spared no effort to get to know “Negro leaders.” He reached out to individuals and heads of organizations, meeting them individually and in small groups. There were Sunday lunches at his home and dinner meetings at the elite, all-male Century Club. The Century round-tables became a kind of an institution in themselves: a dozen or more black and white men, from government, social work and academia, would gather on the club’s musty top floor and take turns around the table, each speaking his piece, then removing their jackets and arguing late into the night.

But even as he studied, Bundy did not wait to begin handing out Ford money. He started with fairly safe, established black organizations: the NAACP, the Urban League, a handful of all-black colleges, and Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. All were middle-class and solidly integrationist, though Bundy caught a glimpse of the trouble ahead when journalists asked if he was nervous about funding King, who was then planning a march to cause “massive dislocation” in Washington. In answer, Bundy grimaced slightly and recited the then-current cliché: “Picketing is better than rioting.” In his first two years he doubled the amount of money dispensed by the national affairs division, much of it for race-related programs, paying out some $40 million in 1968.

Nor did his efforts stop with national civil-rights groups. The shifts in the movement–from South to North, and from legal to economic issues–put pressure on the foundation to look to the ghetto’s grassroots. In a sense, in this, Ford was only following up on its own early initiative: the foundation’s Gray Areas program, working in six inner cities in the early 1960s, had pioneered the idea of helping the ghetto help itself. But in 1964 the War on Poverty had taken the notion one step further, urging “maximum feasible participation” by the poor as a virtue in itself–calling on ghetto people not just to help run local services but teaching them to organize politically so that they could bargain with the government. As the idea gained credence, the emphasis of many anti-poverty programs shifted away from health care and education and job-training-to teaching “leadership” and in effect telling “whitey” off. Some people at the foundation were troubled by this new development. But they were largely unable to resist the growing pressure for any and all kinds of participatory programs. And it wasn’t long before Ford found itself paying for street gangs and avowed Black Power leaders.

Among the most controversial of these grants went to the Cleveland chapter of CORE. Like even the most moderate civil-rights organizations, CORE had been drifting leftward through the 1960s. Its integrationist national director James Farmer had been replaced in 1966 by the younger and angrier Floyd McKissick, who along with Carmichael was among the first proponents of Black Power. Outflanked on the left by SNCC and even tougher ghetto leaders advocating violence and a separate black nation, McKissick felt under strong pressure to prove his militancy. He began to talk of “revolution” and to forge links with black Muslims; he explicitly repudiated the phrase “civil rights,” replacing its appeal to morality with bristling talk of race-based “power.” Before long, his escalating racial rhetoric had driven most white members out of CORE. By 1967, SNCC had actually expelled whites, and in July CORE deleted the word “multiracial” from its constitution. With this, it dropped all pretense that it was pursuing integration or the hope of progress based on racial harmony.

None of this apparently bothered the Ford Foundation, which announced two weeks later–even as the Newark ghetto erupted in riots–that it was giving $175,000 to CORE’s Cleveland chapter. Bundy explained at a press conference that his board had considered the grant “with particular care.” (In fact among some 16 trustees, only Henry Ford himself had expressed any doubts.) What’s more, said Bundy, “neither Mr. McKissick nor I suppose that this grant requires the two of us–or our organizations–to agree on all public questions,” The foundation had chosen Cleveland because it had been particularly hard hit by riots the past summer; Ford’s theory was that CORE might channel the ghetto’s grievances in a more constructive way, averting further violence in the streets. The money was earmarked for voter registration and the training of community workers who were then to help other blacks articulate their needs.

One year later, when the grant came up for renewal, the results were mixed at best. The voter registration and education effort had apparently been successful. Thanks, it seemed, to Ford and CORE’s efforts, blacks came to the polls in significant numbers that fall to elect Carl B. Stokes as mayor–the first black mayor of a major American city. In a sense this was exactly what Ford had hoped for–a channeling of black activism away from militancy and toward more mainstream politics. As it happened, neither Stokes’ opponents nor several members of U.S. Congress saw the issue quite that way, and many people felt that Ford had stepped out of line by interfering in a local election.

The other half of the grant produced equally controversial results. Several dozen youths, most of them high school dropouts, were paid $1.50 and up an hour to attend classes at CORE headquarters. Courses focused on black history and heritage but also on what one CORE official called the “decision on revolution or not.” A black city councilman who opposed the program said the youths were being taught “race hatred” and that they had been heard telling younger children that “we are going to get guns and take over.” Yet Ford continued to defend the grant: “I see it,” said a foundation consultant, “as a flowering of what Black Power could be.” In August 1968, the program was renewed, with explicit instructions to include local gang leaders.

McGeorge Bundy was not a man given to self-doubt. (He once cut off discussion at a foundation meeting by announcing to a group of program officers: “Look, I’m settled about this. Let’s not talk about it any more. I may be wrong, but I’m not in doubt.”) And if he had second thoughts about the path down which he was taking the foundation, he did not express them at the time. Indeed, his speeches and writings in that period showed a confident determination to continue working with black militants.

Bundy’s reasoning on the issue was not unsound. He was not, for the most part, naive about the mood in the black community. He saw the range of sentiment–from what he called “the preachers of hate” to “the great mass of Negroes [with their] patient determination and persistent good will.” And throughout his years at Ford, he continued to fund a range of black opinion–including people as moderate as Bayard Rustin and the Southern Regional Council. (Even in the most experimental years, grants to political activists accounted for no more than 10 percent of all giving.) But Bundy also recognized shrewdly that it made no sense to fund reasonable-sounding and perhaps likable black integrationists if they had no following in the ghetto. In effect, he grasped the limits of top-down social engineering: he saw that to be effective he had to reach black people where they lived, speaking their language, accepting their world-view, and, somehow, dealing with their real anger.

If he made a mistake–and he clearly made some–it was in underestimating the ferocity of this anger. Even this was perhaps an understandable mistake. When Bundy awakened to the issue of race in 1966, he was genuinely horrified by the level of white prejudice he saw all around him. Starting from that perception, he easily accepted the view, made popular in the 1968 Kerner Commission report on the riots, that white racism was the heart of the problem–and that if it could be eliminated, the rest would eventually solve itself. To Bundy, and to many liberal whites, this meant that black anger was somehow secondary, understandable even–justified. Bundy’s preface to Ford’s 1967 annual report, one of his most insightful writings on the race issue, talks–without a hint of defensiveness-about “legitimately militant black leaders [and] their properly angry words.” Besides, he was convinced, this anger would eventually pass. It apparently did not occur to him that by funding young radicals he might only encourage them–might seem in effect to be rewarding them for their militancy.

Nowhere did his conviction go as disastrously wrong as when Ford involved itself in the New York City school system. The tensions that erupted there had been brewing since 1954, when the city’s blacks began to demand desegregation. For more than a decade, they tried to sway school authorities, first calmly, then impatiently, then with growing anger. In theory, the Board of Education was entirely amenable to their requests, supporting the idea of desegregation with its full weight. In practice, the Board dragged its feet–instituting a series of half-hearted measures (voluntary busing and the like) that made virtually no dent in the increasingly stark black-white pattern in the schools. Finally, in 1966, just as Bundy was learning his way around the city, the black community changed course–all but abandoning its call for desegregation and demanding instead that the Board of Education allow them to run the ghetto’s schools.

To Bundy–and most of the city’s white liberals–this made a good deal of sense. Desegregation seemed impossible in New York–for simple logistical reasons, if nothing else. (Besides, many white parents were determined to resist it; and if blacks were no longer very interested, it seemed foolish to press the point.) Community control of the schools seemed to promise more parental involvement, and thus more interest and effort on the part of kids. Besides, if a little Black Power in the classroom could make the schools more responsive and more relevant to students, perhaps their reading and math scores would improve.

Once convinced, Bundy swung into action with characteristic force. He made his views clear to his friend, Mayor John Lindsay, who promptly enlisted him in the battle to wrest some authority away from the Board of Education and share it out among local community groups. A panel chaired by Bundy drew up the city’s official plan for what it called “decentralization” of the school system. In addition, to move the process along, even before his panel had completed its work, Bundy brought the Ford Foundation into the controversy–working around the Board of Education to fund experimental community school boards in three black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods.

Lots of knowledgeable New Yorkers warned the mayor and his allies that they were playing with fire. These skeptics–mostly white teachers and principals, but also a few centrist blacks and Puerto Ricans–argued that many community activists were interested only in power and patronage, that the city’s children would be lost in the scuffle, and that any hope of integration would die under this plan. Bundy, ever sure of himself, ignored the warnings and pressed ahead with the program. In part, he was simply naive: he didn’t see what kinds of angry and intransigent people were waiting in the wings to form the local school boards. He was also convinced that he could have his cake and eat it too-that he and the city need not choose between Black Power and integration.

Despite the black community’s increasing disaffection with the idea, Bundy himself remained firmly committed to the goal of integration. In the narrowest sense, he made clear in the report on decentralization, he believed in the educational value of school desegregation–in the simple mixing of black and white children. But beyond that, Bundy also held to a larger vision of an ultimately integrated society where blacks and whites would participate equally in shaping American life. His preface to Ford’s 1967 annual report makes the point with passion and great persuasiveness: “Apartness will not be enough…the Negro, like everyone else, has a right–and obligation–to play his part in the society as a whole.” If nothing else, he argued, “there is only one bar and bench, only one system of government, only one national marketplace, and only one community of scholars.” As Bundy saw it, there was no real choice: reluctantly or not, blacks would eventually opt to participate in the American mainstream.

Yet, paradoxically, he was also convinced that community control, and indeed black nationalism, might be stepping stones on the way to integration. If blacks could improve their own schools, educate their children and bolster their pride by asserting Black Power, they might then be in a better position to take their place in the integrated mainstream. It was, in its way, a noble vision. It recognized black needs and black insecurities, it honored blacks’ dignity and their special “apartness”–yet it also held out a glittering vision of ultimate harmony between the races. Indeed, in the long run–over the span of decades–Bundy’s vision may be the only acceptable one. It was not to be in New York City in 1968.

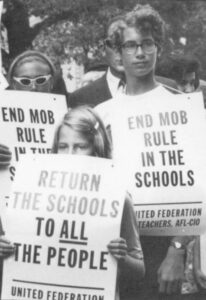

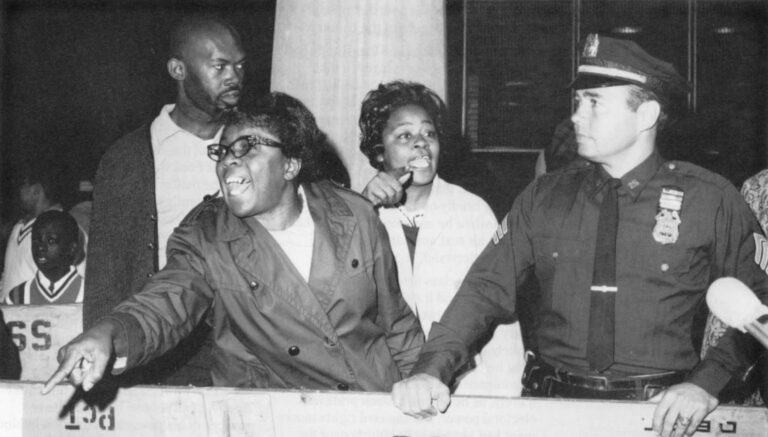

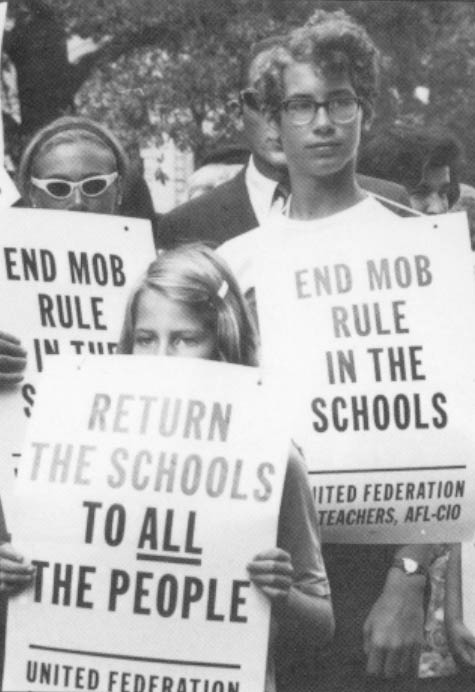

Everything the skeptics predicted–and more–came to pass in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, one of the three experimental districts funded by Ford. Within weeks of the foundation’s $59,000 grant, the militant activists who made up the board in this forsaken Brooklyn ghetto found themselves at odds with some dozen allegedly “incompetent” teachers charged by the board with being disloyal to the decentralization experiment. (The board was largely black, the teachers were white–and even a black judge who later investigated the dispute could find little cause, apart from race, for the board’s dissatisfaction.) In May 1968, the offending teachers were asked to leave their posts, and when the union rallied to their defense, the local board went to war against the union. The union struck; the board resisted-by hiring several hundred irregular teachers and organizing people from the ghetto to demonstrate at the schools. Then, throughout the fall of t968, the Ocean Hill-Brownsville schools were the scene of daily violence.

A typical day brought out pickets and counter-pickets, shouting at each other across wooden police horses, threatening each other and inciting schoolchildren. Both sides organized rallies at City Hall; both spread hateful and largely racial innuendo. Black anti-Semitism (many of the teachers were Jewish) vied in fury with whites’ race-charged fear and anger, and the cumulative venom spiraled out of control. The eight schools in the Ocean Hill Brownsville district were at the center of the storm–and many white teachers there reported they feared for their lives. But the striking union gave as good as it got, spreading bitterness throughout the city by shutting down the entire school system and causing more than 1 million students to miss nearly 40 days of the fall term. By November, when the strike was settled, integration–and race relations in general–had been set back 20 years or more.

In the end, state education authorities approved a much watered-down version of the Bundy panel proposals. But Ford was made to pay dearly for its activist involvement. Conservative journalists and congressmen riding the backlash of the late 1960s seized on the foundation’s involvement in both Ocean Hill and Cleveland. These were only two small grants, a few hundred thousand dollars of the many millions Ford had spent on race relations–for education, voter registration, housing integration and poverty research. But that did not stop critics like Texas congressman Patman Wright, who suggested apocalyptically on the House floor that, “the Ford Foundation [had] a grandiose design to bring vast political, economic and social changes to the nation in the 1970s.” Thanks largely to his efforts, in 1969 Congress passed legislation that significantly restricted all foundation giving (not just Ford’s) with excise taxes and federal oversight.

Ford never exactly repudiated community control–or Black Power. Nor did it give up entirely on Bundy’s paradoxical idea that the best way to spur integration was to bolster separate black institutions and strengthen black identities. Yet Bundy and his officers quietly retreated to a far safer form of black-institution-building–investment and grants for ghetto-based enterprises known as “community development corporations.” Pioneered in the late 1960s by Robert Kennedy and the Rev. Leon Sullivan, CDC’s are now a mainstay of the foundation’s work. The theory is simple: Ford-and the government and private lenders-funnel money to a local nonprofit “board” that builds up the neighborhood and tries to attract business. These businesses create jobs, while the “corporation” –acting as a kind of local government–provides an array of social services. In the past 20 years, Ford has spent some $200 million on what it now estimates to be 2000 CDC’s.

The difference between today’s CDC and the community activism of 1960s is small but critical: participation is still the key word, but the emphasis is on substantive participation–community involvement in a particular activity like rehabilitating local housing–rather than on participation for participation’s sake. Success is hard to measure. Few of these “corporations” could exist without outside support: yet to Ford and to the communities that host them, they represent an important kind of “self-help.” And that, for the moment, is still the most urgent priority–with the goal of integration still deferred indefinitely.

What about Bundy’s larger ambitions–including his dream of an ultimately integrated society? If nothing else, the 60’s and 70’s taught him that the world was a more complicated place–less rational and readable and open to change–than he imagined as a young man in the Kennedy White House. His writing about race changed noticeably over the years, growing if any thing more concerned but also a little more melancholy, filled with an increasing sense of just how hard it is to change American hearts and minds. Gone is the confidence of Stimson, Acheson and Kennedy; gone is the certainty that one can teach society what it needs. In particular, the more Bundy worked on racial matters, the clearer he saw that no social engineering could simply undo 300 years of history. No one, overnight, could simply eliminate the bad attitudes built up on both sides over generations of scorn and fear. And so, always the pragmatist, Bundy began to look for strategies that would take account of these entrenched difficulties.

It was this understanding that produced his last, and perhaps most significant, achievement in the realm of race relations–his role in the Supreme Court’s Bakke decision endorsing the use of racial criteria in university admissions. Bundy’s contribution was an article in The Atlantic making the case for affirmative action. It was, even for Bundy, an unusually subtle and brilliant argument–but if that was all it was, it would hardly matter today. What made it important was its impact on one particular reader: Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun, who provided a crucial fifth vote in favor of the use of racial criteria. His short opinion on the case was so close to Bundy’s piece that it all but quoted him. “Precisely because it is not yet ‘racially neutral’ to be black in America,” Bundy wrote, “a racially neutral standard will not lead to equal opportunity.” Thus, he concluded. “To get past racism, we must here take account of race.” Blackmun borrowed the phrase almost verbatim, and it has stood for a dozen years as the nation’s primary rationale for affirmative action. For better of worse, it encoded the key idea of the late 60s-that racial progress can come only through racial consciousness-at the center of American law. The distilled essence of Bundy’s thinking on “the Negro question,” it remains a telling emblem of all that he did to encourage black consciousness and race-based strategies.

Controversial as the argument was–and remains today–in Bundy’s view, it was simply pragmatic. From the start of his career at Ford, he had realized that one must see the world as it was and work with Americans as one found them, however backward on the matter of race. Integration and color-blind laws were certainly his goals, but he saw no point in insisting on them before Americans–both black and white–were ready. As a working assumption, this is hard to argue with-and it has helped make Ford a critically important force in alleviating the symptoms of American race relations. If the foundation has not accomplished more than that–and certainly not McGeorge Bundy’s expansive goals–he alone can hardly bear the blame. Even his cool mind and best intentions could do only so much to ease the American race problem.

©1990 Tamar Jacoby

Tamar Jacoby, a freelance writer, is researching race relations in several American cities.