Glamorous young mayor John Lindsay had been in office all of two months when he threw down the gauntlet on the issue of civilian police review. The occasion, in February 1966, was the inauguration of a new police chief, a man known to be committed to civilian review. “I intend to offer new solutions,” Lindsay declared over the airwaves, “and every one is going to disturb the tired, self-perpetuating bureaucratic ways of the past. Jobs will change. Deals will be canceled. Fat and easy lives will be disrupted.”

Police in the audience bristled, but lots of other New Yorkers cheered, thrilling to the mayor’s boldness and his take charge reformism. I cannot promise you a peaceful administration,” he continued. I cannot promise you that you will not continue to hear the howls of the power brokers…But I can promise you change and reform and progress. One of Lindsay’s most famous speeches, it caught everything that made him inspiring-and also bitterly resented-as mayor.

By the time he actually created the civilian review board, three months later, all of progressive New York was ready to rally behind the cause. Both ‘The New York Times and The New York Post supported the idea. So did the NAACP, CORE and the Urban League, but also, downtown, the ACLU, the Liberal Party, the City Bar Association, the Anti-Defamation League and the Council of Protestant Churches. When it emerged that the Policemen’s Benevolent Association was going to oppose a civilian board, Lindsay’s young media advisor, David Garth, organized a coalition known as FAIR. Anyone who was anyone in liberal New York rushed to join: black and white, Republican and Democrat, whiteshoe elite and ghetto grassroots. The long list of members included most of the city’s known-name lawyers, elected officials, union leaders, Manhattan clergy and a host of celebrities: Henry Fonda, Eli Wallach, David Susskind, Paddy Chayevsky and Sidney Lumet.

Never before, North or South, had the establishment of a big city risen quite so unanimously to meet a demand from the black community. In 1966, whatever Lindsay sometimes felt, New York’s power brokers were still unashamed, big-L liberals, keen to do the right thing in the name of civil rights. Already in 1966-in marked contrast to the early 60s-the white consensus on the right thing had eroded a good bit. The most obvious racial barriers had been removed; legal discrimination had been eliminated. Still, the ghetto festered and blacks bristled with impatience. Across the North, whites of good will were wondering what to do next. In New York, the civilian review board seemed the answer.

In 1966 as today, support for police oversight struck many liberals as a dream investment: it required little capital of any kind, looked virtually risk-free and promised a huge payoff in relations between blacks and whites. Like the civilian board at issue in New York today, Lindsay’s proposed panel would not have meant much real change. The police department already had a division that investigated abuses; all that Lindsay did was staff it partially with civilians. Like the board being created today, his concerned itself only with minor rule infractions; any incidents involving illegality on the part of the police were passed on the usual legal authorities. Also like today, Lindsay’s board had no enforcement powers. It stopped short of reforms such as changing the command structure, discipline procedures or accountability.

At the same time, like today, Lindsay’s supporters felt it was critical to back the new review board lest they look unsympathetic to the ghetto. It was clear to the mayor and others that civilian review Would not fix all that was wrong with race, relations. Still, white liberals felt the race problem was surely solvable, and the solution must start by establishing a sense of trust between black and white. Begin with the civilian review board, prove that while society cared- then move to other, concrete problems, like deteriorating schools, housing and job base.

For most whites, in 1966 as now, the review board’s biggest, selling point was that it was what the ghetto said it wanted. At the very least, advocates reasoned, it would calm rising black anger.That the problem might be deeper, that angry blacks might not be appeased by a gesture, that many city whites might not understand and might feel badly slighted: none of this was clear in 1966, as it apparently is still not quite clear today. Idealistic whites were not wrong to make interracial trust their highest priority. What they miscalculated was just how hard it would be to establish-how differently black and white New Yorkers would see police issues, and how trying to force a solution could expose and expand that gap.

Lindsay and supporters were certainly right that something had to be done about relations between the police and the ghetto. Then, as today, blacks saw police abuse as one of their foremost problems. In New York as in other cities, these gripes were often justified. City cops were rough if not downright brutal and often inclined to take frustrations out on blacks. At the same time, many ghetto youths knew no whites other than surly policemen and focused resentment on them, making tensions worse.

The idea of creating a civilian panel to oversee the New York force had surfaced in the 50s. The original proponents came from the militant fringe of the community. Malcolm X himself first became known to city authorities after an incident in which an angry Muslim mob threatened to storm a Harlem precinct. By the early 60s, more moderate leaders had taken tip the banner, in part at least to establish their bona fides among the restless youth who were being drawn increasingly to Malcolm X and other militants. There was plenty else amiss in Harlem, but centrists like Martin Luther King and CORE’s James Farmer had a hard time getting black audiences to focus on them–particularly when there were so few obvious answers to offer. Before long, the city’s largely white Liberal Party had backed civilian review. Police and business groups joined forces and momentarily buried the idea-until the summer of 1964, when rioting in Harlem brought the problem back.

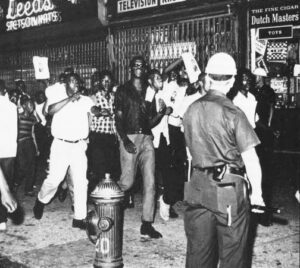

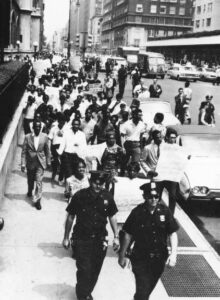

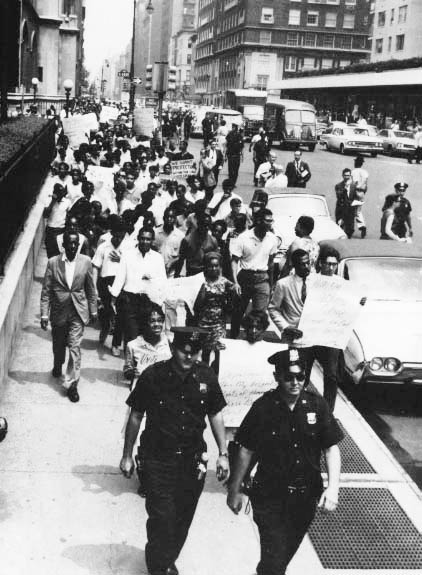

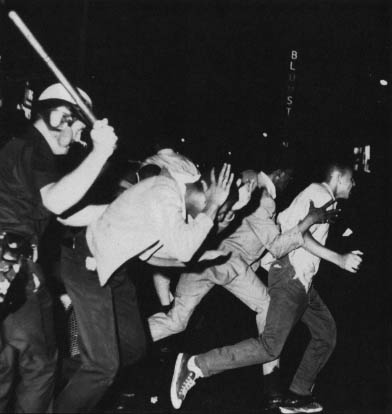

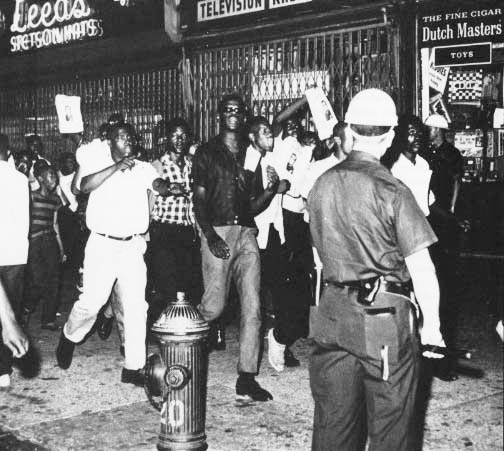

Like virtually all riots since, tile disturbances began with an incident between a cop and a black youth. Rumors swept the ghetto; the incident was quickly exaggerated; before long, looting and arson had turned into a pitched battle with police. There was little question that some officers went overboard. When the dust had settled, all of Harlem stood together, moderates and militants united in their insistence on civilian police review. By the time Lindsay declared for mayor, in the spring of 1965, black demands for oversight had a hard, angry edge: a reasonable request, long denied, had become an accusatory ritual. The fact that it was blacks’ first priority spoke volumes about the city’s racial climate.

From the beginning there were plenty of clues that civilian review was a grudge laden issue. Similarly, there was ample warning that it might not sit well with lots of middle-class whites.Their doubts were apparent if not yet formed by the time of the 1965 mayoral election, when Lindsay’s conservative opponent, William F. Buckley, vilified police review from one end of the city to the other.

Buckley’s argument was characteristically blunt and often mocking. Crime was rising, he said, much of it was committed by blacks; but poor blacks were also bearing the brunt of the violence, and they welcomed a tough police presence. It was demagogues who had made an issue Of police brutality-a phony charge, he maintained, certain to make life even less safe in the ghetto.The presentation convinced many middle-class whites, who had no idea of the different lens through which most blacks viewed cops. Parents, taxpayers, homeowners, shopkeepers: whites in the outer boroughs looked at the issue through their own prism-and as they Saw things, the clear, pressing problem was rising crime.

For Buckley, the issue went further, beyond delinquency or police comportment. What bothered him was the nature of the militants’ arguments, which he saw as dishonest and racially manipulative. Again and again on the campaign trail, he tore into the black claim being put forward by James Baldwin and others that black crime was a form of social protest. Buckley’s rhetoric, like his campaign, was subtle and sometimes insidious: one part reasonable argument and one part veiled appeal to prejudice. His followers were a mixed bag, though already in 1965, it was hard to tell the outright bigots frown the frightened, confused people wondering how to think about race and crime. The one certainty was the gulf between black and white. Ghetto and boroughs looked at the same phenomenon, and when they tried to describe it, sounded as if they lived on different planets.

Lindsay made an initial effort to bridge the gap, rejecting militant black demands for an all-civilian review panel. His com promise proposal included officers as well as outsiders, with civilian members just outnumbering those in uniform. Though meant to ease white objections, this immediately drew fire front all sides. Yet when it did, instead of trying harder to forge a consensus, Lindsay simply barreled ahead, imposing his own view. Confident and righteous, he still believed he could ignore the bigots and militants. Eventually, he reasoned, civilian review would win both sides. Like much of Lindsay’s politics, this was an appealingly idealistic assessment. The trouble was that he could not revise it-even when it proved to be dead wrong.

The issue simmered on and off through the mayor’s first months in office. From opposite ends of the city and the political universe, police commissioner Vincent Broderick and militant CORE activist Roy Innis both called the mayor’s proposal “a cruel hoax.” Black militants and the Police Benevolent Society both promised massive demonstrations. Still, Lindsay ignored the flak. This will pass, he said, once the police go through the motions of trying to block the board.

The mayor moved by executive order to create a review board. Ethnically diverse, mixed police and civilian, it was to operate according to strictly defined due process. Publicist Garth was brought in to package the idea as decent and reasonable. Neither the hard sell or the legal safeguards had much impact. New Yorkers, left and right, perceived the issue as a test of tribal loyalty.

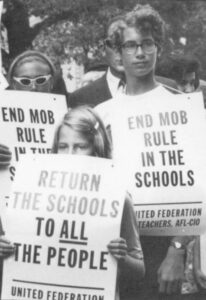

Few people in the city was unsure where they stood on the issue. The Daily News kicked off the resistance effort, calling the mayor’s order “the property of bleeding hearts and cop-haters.” Patrolman John Cassese, an activist with the Police Benevolent Association, declared it illegal. He went on TV to announce that the PBA would spend its entire treasury-the then-huge sum of $1.5 million-to kill the idea. Insisting that the mayor had acted without due authority in creating the board, the PBA began collecting signatures to put the issue to a vote in November. Right-wing groups rallied to the policemen’s side: the Conservative Party, the John Birch Society, the American Renaissance Party and the American Nazi Party. By July, the PBA and the Conservative, Party together had collected more than 91,000 signatures, more than three times as many as they needed.

The conservative opposition drew on a potent mix of feeling-caution in the face of change, bureaucratic self-interest and, from some quarters, undisguised racial resentment. Many cops, preoccupied with power and prerogatives, could not brook the interference from outside. Others felt that Lindsay was, using their department carelessly to make a gesture to angry blacks. Still others were worried that the extra scrutiny would tie their hands in dangerous situations, endangering them and the people they were trying to help.

Friends of the board did not, at first, appreciate what they were up against. New York’s liberal establishment poohpoohed the board’s cranky, fringe opponents. Lindsay was thrilled when the John Birch Society came out against the panel. He did not bother to refute the Birchers’ arguments, but simply denounced them as “highly organized, militant, right-wing group.” Campaigning around town, he drew attention to the openly racist literature of the neo-Nazis opposed to the board.

The opposition did include some virulent racists. But already in 1966, the charge of bigotry had a McCarthyite edge to it: once you found someone “racist,” You no longer had to argue with him. Justified or not, Lindsay’s dismissal of the PBA’s claims rankled the many ordinary citizens who were not sure where they stood on the issue and badly wanted to hear some more substantive debate. As for those who opposed the board for what they felt were valid reasons-fear of crime, loyalty to the police or even simple ignorance of the black experience-they resented being labeled as racist. Many who might have been open to argument were annoyed by the mayor’s contemptuous attitude, and their initial opposition grew only more entrenched. Instead of explaining his reasoning, or helping whites see things from a black perspective, Lindsay only sharpened the polarization of black and white.

As the summer wore on, liberals saw they had miscalculated, but instead of strategy they became more combative. The idealism drained out of their campaign speeches; arguments grew more and more defensive. Advocates had never been very good at showing how the board would improve race relations. Now they now longer even made the claim; they simply justified themselves. Finally, when they could think of nothing else, they went on the attack.

One morning in July, two PBA spokesmen had breakfast with the mayor. “I told them,” he reported later, “that if anything happened in New York-it there was a blow-up-they would be responsible.” Giving up all hope of winning over uncertain white voters, Lindsay tried to bully them with threats of looming race riots. By now, both sides were talking past each other and playing on white racial fears-whether of crime or riots hardly mattered.

By the end of the summer, the campaign conceived as a way to encourage racial trust was stirring up mostly paranoia and prejudice.

The battle grew more bitter as the city headed into fall. Lindsay was heckled as he made his way around town. “Why do you always kowtow to the coloreds?” yelled one woman in Flatbush. Uptown, too, people saw the issue more and more starkly. “The arguments against the board are shorn of their sophistry in Harlem,” said black state senator Basil Paterson. “We in the ghettos have heard it before…‘If you’re black, get back.’” The misunderstandings of 1965 had hardened into fear and hatred, as the referendum pitted one side against the other.

By mid-fall it was plain that liberals had scant chance of winning. For all the glittering backers who had lined up behind the mayor, the PBA had raised five to ten times as much money. The press saw the writing oil the wall and called the coming rout. The mayor has “jeopardized his political future,” one columnist said, “because of the enemies he’s been making” instead of finding a way to bring blacks and whites together, guiding them toward understanding and compromise, Lindsay and supporters had allowed tile situation to degenerate, with no middle ground and no way out.

The only surprising thing about the vote was the margin: 63-to-36 percent in favor of abolishing the panel. Of the city’s five boroughs, only Manhattan voted for it. Roman Catholic voters came out 5-to-l in opposition. Jewish New Yorkers joined them by a margin of 55 to 40 percent. Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods were for, as expected, but the turnout there, unlike in the boroughs, was dismally low. The overall outcome was all the more dramatic given New York’s long liberal history. This was the first time in decades that city voters had rejected a progressive cause, turning their backs oil civil rights and shrugging off a black demand.

One team of social scientists, working at Harvard in 1969, tried to correlate the vote with a survey of attitudes taken in a middle-class white neighborhood in Brooklyn. Edward Rogowsky, Louis Gold and David Abbott found, as they expected, that “on balance, race was the most significant factor” in the way people had voted. Yet unlike those partisans who felt that anyone who opposed the panel was a bigot, these pollsters found that Brooklynites-even those who had gone against the board-held strikingly ambivalent attitudes about color. Three quarters of the Brooklyn respondents said they would not mind a middle-class black family in their neighborhood; 85 percent believed that “Negroes learn as well as whites.” The rejection of the review board had not, the Harvard team found, been a signal that most white New Yorkers were inherently “racist.”

What it did signal was more complex and, with some leadership, perhaps avoidable. Certainly, in 1966, most whites had no idea what blacks regularly suffered at the hands of policemen. Many whites could not comprehend blacks’ fear and resentment of blue uniforms-and blacks could not understand why whites did not get it or care. Beyond that, by 1966, many whites were truly frightened by the city’s growing crime rate – they did not have to be racists to vote against a measure that seemed likely to put them at greater risk.

More important though, according to the Harvard team, middle-class whites were scared by [he anger that was surfacing in the black movement. More than two-thirds of the Brooklyn whites thought it was turning in a “generally violent” direction; they disliked the protest for protest’s sake and the bitter talk of separatism. Whether or not they liked blacks, and many probably did not, what they feared was the spiraling pressure for change-pressure that no one in the government seemed willing or able to resist. Blacks had mounted an angry challenge, and instead of trying to mediate it, City Hall had baldly taken their side. What the episode seemed to prove, for many whites, was that there was no longer a referee-and that in order to protect themselves, they had better hand together tribally.

Well, short of bigotry, then. The review board vote showed just how easy it was for race relations to spin off track-easier for black and white to misread than to hear each other, easier to overreact than to listen and respond. Certainly, by 1966, it was easy for whites to blame the protest movement and to cite its excesses as a rationale for resisting change-especially if they wanted to resist in any case. To those who were deeply racist and to many who were not, angry color-coded demands had given whites an excuse to act their worst-to hunker down, to block reform and to vote as selfishly as they liked.

Could Lindsay and his supporters have convinced them otherwise? Could he have proved that racial politics were not a competition, or eased the fearful jockeying that divides all rival tribes? Maybe not. But as it was, City Hall did not even try-and instead played right into both black and white insecurities. The campaign rhetoric had been chilling-and it augured worse to come, encouraging both right and left to trade in blatant racial appeals, fueling the politics of blame and fearful color-coded resentment. From now on, few New Yorkers would be embarrassed to make race an issue, to vote their fears or their prejudice. Each side was now convinced that the other was its natural energy, and both would react defensively to any future exchange.

So, turn for turn, each side fed on the other’s mistrust and resentment. The liberal establishment that forced the vote could not be blamed for its good intentions or even its ignorance of the fear and anger that divided one side from the other. What’s harder to understand is why so few of these white idealists were able to recognize their mistake-to see the fight they had encouraged and back off before it got worse, guiding the city toward compromise instead of bitter standoff. More than 25 years later, it is still a troubling question, as the city totters again on the brink of the same chasm.

©1993 Tamar Jacoby

Tamar Jacoby is a freelance writer in New York City examining racial politics in several U.S. cities.