It was 1968. Arnetra Johnson, a black woman raising four bright-eyed babies alone in a rural North Carolina trailer park, was holding fast to the dream just as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had laid it out: black boys and white boys sitting side by side in the same classroom. She agreed: one day her children would attend the great integrated schools up north, far from the unenlightened, still segregated south. Didn’t her youngsters deserve the finest institutions America had to offer?

She listened closely for whispers, rumors, promises of opportunity that some said would come flowing from the blood of Dr. King and others who fell for civil rights.

Church sermons prophesied it. Newspapers reported programs, acts of Congress. Then came tire letter from her well-educated brother-in-law in Atlanta. He had heard about a special program that sent smart black boys and girls like hers away to private schools-,’the best in the country,” he wrote: For free.

The program was called A Better Chance, Inc. (ABC). It was the benevolent brainchild of a visionary band of New England prep school headmasters. Since 1964, they gave scholarships to move smart black boys and girls out of city slums and dead-end towns like Wise, North Carolina into Andover, Choate, Phillips Academy and eventually, Ivy League colleges.

ABC’s mission: To cultivate the “Negro leadership” that would pave the road to a divided nation’s integration.

To Mrs. Johnson, ABC was the sure ticket to those northern universities. She would press it into her children’s wanting hands.

“I thought it was the magic answer,” Johnson recalled. “I was so hung up on the integration movement. I just wanted them to go to a big northern college. I thought because they were in prep school they would automatically be accepted to one. I wanted them to have exposure, to be part of the new integrated America.”

At first, the ABC magic worked splendidly. But then it seemed to backfire. ‘Me Johnson sisters’ ABC experience is practically a model case study of the program’s strengths and weaknesses.

Like a fairy godmother, ABC delivered daughter Sondra, the oldest, to a golden nest of opportunity: from Abbott Academy to Harvard, to the University of North Carolina, and a corporate engineering post.

But the prep school fizzled for her sister Fran. She stumbled through, working too hard to fit in with the Docksider set in the dorm, and not hard enough to compete in the classroom. She lost direction, drive. College took eight years to complete. Her career as an accountant has been unfulfilling.

Mrs. Johnson’s two sons also attended private schools, though not through ABC. They too lost momentum, barely managing to graduate. They drifted in and finally out of college.

Nearly 30 years have passed since those headmasters cut the first ABC tickets. Today a generation of nearly 8,000 ABCers has come of age. As the century of civil rights comes to a close and America reflects on her racial progress, the question is inevitable: What has become of the children of perhaps the most daring and long-lived educational and social experiment of the Great Society era?

Like Sondra, did most live up to the program’s promise to cultivate a cadre of elite black professionals? Or like Fran, were they derailed and delayed on that road?

The answer lies in ABC’s 30-year battle to survive as a non-profit minority talent search agency: from the fat days of the Great Society when the federal government was eager to invest in integration; to a time when Uncle Sam and once-generous philanthropists dried up on the ABC dream.

The non-profit Boston-based agency still operates today, sending about 300 youths to prep school each year.

The answer of what became of its first alumni is tangled up in the changing attitudes and ambitions of ABC students. That first batch of ABCcrs in the 1960s was driven by poverty and hardcore segregation to shine at eastern academies.

But in the next decade, some ABCers may have been distracted, and perhaps, deceived by a world that no longer was drawn starkly or simply in black and white.

Interviews with 75 ABC alumni from Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York City and Washington, D.C. turned up an array of well-educated, impressively credentialed middle class blacks. They stand as testament to ABC’s boast that nearly 99 percent of its graduates enter college.

They recounted the journey from poverty to prep school and beyond as risky, wrenching at points. They recalled those who turned back, unable to go on. For some the experience had become a life-long reference point for personal strength and endurance.

Immersed in an unfamiliar, wealthy, white world at a tender time, most shadow boxed with their own racial identity. Most emerged with their psyche and black souls intact. Today they are at peace with their assimilation.

There was Jeffrey Palmer, a graduate of Kimball Union Academy and Princeton, and co-owner of one of the largest black-owned printing companies in the country. His home is a spacious Chicago condo. A gilded painting of his wife hung over the mantle.

“I got in a lot of fights, with white. boys who called me “n…..”,” Palmer, 42, remembered. “Mostly, I am grateful to ABC because it opened the world for me. And it kept me out of Vietnam when all my buddies from Steubenville, Ohio, were getting drafted. They came back damn near psychotic.”

Of the 75 interviewed, 11 fumbled prep school academics and later dropped out of college or took years to graduate. Prep school, some conceded, had knocked them flat and confused. For them, years after graduation, anger, angst and inertia linger.

Among them was Jimmie McVey, a 1974 graduate of the Storm King School in upstate New York, which is now closed. He could still remember feeling as if his classmates were cons ahead of him. “It was like I had been brought up to do things the wrong way,” said McVey, 37. “1 was lacking. Their whole thinking process was different. They dealt with the world different.”

He found little guidance from ABC. College just didn’t work out. He sweated in a Chicago steel mill until a 1988 layoff. After four years of unemployment, he now welds in an auto parts plant for about $10 an hour.

Some wondered whether they would have been better off if they had stayed at home in backwoods and tenements.

Mrs. Johnson’s oldest daughter Sondra, 39, believes she is better for her journey from that trailer in Wise, North Carolina, with its one-microscope school.

But Sondra has second thoughts about Fran who tried to march in her footsteps.

“I feel very strongly that prep school is very good for some people, but not for everybody,” said Sondra. “For my sister, in particular, it was too intense. It ended up taking her a step backward in terms of confidence. I’ve seen perfectly smart kids go away to prep school and Harvard who are now driving cabs or working line jobs. I know that had they stayed home, they could have excelled and become leaders.

“Some people need to be in an environment where they feel good about themselves and have family nurturing,” she said. “We do ourselves a disservice if we automatically try to push and shove all the kids we see as high-potential into so-called excellent environments.

“If I had a child,” she said, “I would surely think twice before sending him to a prep school.”

In 1968, ABC’s elaborate, six-week summer orientation program at Williams College was Sondra’s prelude to prep. Paid for with the help of federal funds, it was designed by ABC to ease the academic and social adjustment students would face at their new schools.

Sondra, sturdy and graceful, excelled academically at Abbott Academy. Socially, she paled on the sidelines in awe of her new peers.

There was Betsy Hoover, daughter of a home appliance mogul. Two doors down in the dorm was the daughter of a food chain vice president.Their families owned cottages on the eastern shore and summered in Switzerland . In winter, they skied. The girls sported Pappagallo shoes. At supper, each fingered her personal napkin ring.

The unevenness of material things did not distract Sondra from her mission. In two years, she entered Harvard as a math major. She graduated on time.

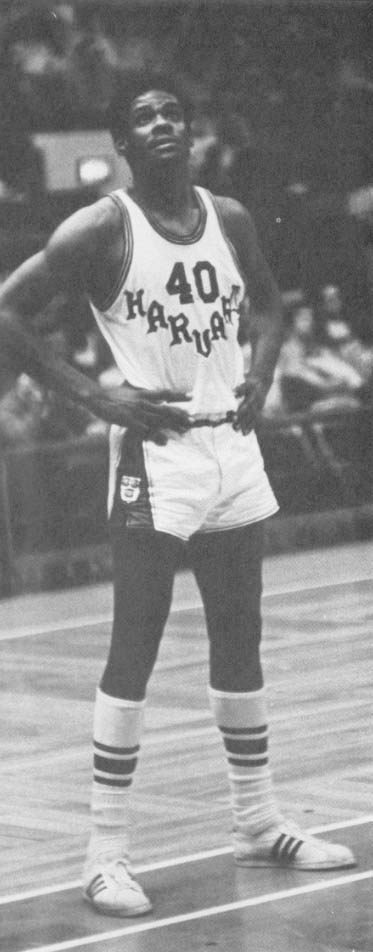

At Harvard, Sondra met her husband-to-be Anthony Jenkins. The son of a Detroit auto worker and a waitress, he too had been tapped by the ABC wand. He landed at Harvard after graduating from the Shattuck School in Minnesota.

After Harvard, Sondra headed back south to the University of North Carolina to earn a masters degree in environmental engineering. Meanwhile, Jenkins graduated New York University Law School. Once back home in Detroit, he called to ask Sondra to marry him.

She believed she could move north. Her family’s future seemed assured: Brother Eric had received a scholarship (not through ABC) to private Cushing Academy in Ashburnham, Massachusetts; and ABC was eager to send Fran to Abbott.

In Detroit, Sondra quickly landed an engineering job. She and her husband settled into America’s new black middle class.

But the long-distance calls started. First, from Eric, who was struggling with confidence after graduating from Cushing and enrolling at Northeastern University. Eric had been comfortable at Cushing, a private school that takes pride in an unpreppy curriculum.

“Going to prep school lowered my awareness of who I was,” Eric, 34, said. “After two years partying up there with them, I thought I was one of them. When you leave, you go back into the real world. If you are not focused, you lose sight of that reality.”

A semester or two away from a Northeastern engineering degree, Eric, on a lark, brought a Yamaha 750 and sped south. Much to Mrs. Johnson’s dismay, he never returned to graduate, But eventually, he settled into a solid career as a field engineer.

Next Sondra’s phone rang with calls from Fran.

At North Warren High School in Wise, North Carolina, Fran, eight years Sondra’s junior, had been an academic and extra-curricular star. She wrote poetry, plays and helped teachers grade papers.

All that changed in 1975 when Fran took the ABC ticket. By then, the school for young ladies had merged with its male counterpart under the name Phillips Academy. No longer the quaint cottages and schoolhouse that Sondra had known, it was now large and impersonal, nearly 1,000 students.

ABC funding had dwindled as the Great Society went out of style. ‘Me once elaborate summer orientation nearly vanished. While Sondra had the luxury of a six-week, retreat-style preparation for prep, Fran received only a three-day orientation.

Fran’s yearning to fit in was stronger than her will to compete. ‘Though she partied, drank, smoked pot, the feeling of belonging never came.

“I could never find my niche,” recalled Fran, 32. “Mat bothered me quite a bit. I spent a lot of time trying to mimic some of the things they did in order to make the grade. It pulled me into a shell. I felt that I was here with all these rich white people who were born with these silver spoons in their months and here I am this little black girl from a country town.

“As far as I was concerned, a lot of them were not bright and I resented that,” she said. “It taught me that it’s not what you know. It really got to me.

“In class, it was as if they spoke a different language with a different alphabet. “One teacher insisted that the poem by Robert Frost ‘Stopping by a Woods on a Snowy Evening’ was about death,” Fran said. “I wrote that it was just about a man who was tired and stopped to take a break. She insisted that I was wrong.”

Disenchantment set in. The drive that had moved Fran from the trailer park to Phillips slowed. Grades dived to C’s, D’s.

ABC was nowhere to be found. Fran vaguely recalled an ABC representative showing up at the school for an occasional student check-up. But there was no consistent shoulder to cry on or ear to listen.

Then as now, ABC officials stressed that its goal is to get students into schools. Once there, it was up to the schools and what minimal support ABC could provide to guide them, said William Boyd, ABC president in the late 1970s.

Those integrated northern universities that Mrs. Johnson dreamed about replied to Fran with rejection letters. Only North Carolina State University would take her. ‘Mere she fumbled through first and second semester while kids she knew from back home excelled. A summer make-up course at Harvard, paid for by her sister Sondra, did not help.

On academic probation, Fran dropped out and moved to Detroit at Sondra’s suggestion. She worked junk jobs. A college course here and there eventually earned her an industrial engineering degree from Lawrence University in 1986, eight years after her graduation from Phillips.

“My mom had aspired for me to go to an Ivy League college. She thought prep school would be a stepping stone,” said Fran. “But my getting into Lawrence had little to do with me going to prep school. It’s a working man’s school.”

Since then, Fran has worked as an accountant with little career satisfaction.

From time to time, she wonders what became of her old academy pals, but never inquires. “With me, it’s a pride thing,” she said. “If I were doing something outstanding, if I were along in my career like Sondra … But good grief,

I went to one of the best prep schools in the country. And for the last few years everything has been so depressing for me career-wise.”

Possessed of clear-eyed honesty and arresting self-reflection, Fran refused to blame ABC. It was simply immaturity. “I didn’t use the prep school experience to do the things I could have done with it.” And perhaps it was displacement. “I didn’t conform. I didn’t become a preppy. I just didn’t.”

After Fran’s phone calls, Sondra received crisis collect calls from Keith, the youngest of the Johnson children. He had followed Eric to Cushing, though not on an ABC scholarship. He too faltered, preoccupied with partying. On the eve of commencement, he was expelled. School officials debated before allowing him to graduate.

Now 30, he is attending a technical school in Charleston, South Carolina. “Not too long ago, he told me,” said his mother, “‘I just want to finish something for once in my life.'”

While her siblings have struggled for a foothold, Sondra has the prestige and challenge of a fast-track engineering career. She carries her prep-school aplomb into corporate decision-making rooms. She takes it with her on frequent business trips to Europe and South America. She is at competitive ease with her white male colleagues.

“ABC gave me exposure to people whose lifestyle, culture, point of view were different from mine at a time when I had the luxury of learning about it, as opposed to later when I had already started a career,” Sondra said.

“You have to hit the ground running. If you are going to work and compete in the corporate arena with the so-called advantaged, you don’t have time to learn how they think and where they came from once you get the job. ABC gives you a headstart so that this is not a foreign environment when you get here.”

Sondra’s husband, Anthony Jenkins, now a successful real estate lawyer, took the high road right along with her.

“When I was first contacted by ABC, my old basketball coach in junior high school reminded me that I might be the first Negro to go to that school.” Jenkins remembered the post-gym class talk as if it were yesterday. He said, “I want you to be as well-prepared as you can possibly be as an athlete, but also in terms of what. you can do in the classroom.”

“I carried that with me through high school,” Jenkins said. “I realize that I was breaking new ground for white people who had never had any contact with black people. I began to think that it was, in large part, a social experiment and I was being tested. I learned how to work hard, really hard.”

As for her siblings, Sondra said, “If they had gone to school in North Carolina, even though it was a poor school, they probably could have made a greater contribution to society.”

Back home in dusty, small-town North Carolina where the residue of segregation lingers still, and the dearth of opportunity for anybody, black or white, staggers the mind, Mrs. Johnson reflects on the maybes.

Would her bright-eyed babies have been better off if they stayed at home? Should they have turned down the ticket?

“Prep school was very good for them,” she said. “Even in talking, they have so much more to say and they say it so much better than others. And it exposed them to so much more.”

“But they didn’t have that inner push,” she realizes. “I don’t know why it was lacking. I’m not disappointed with them or the program. I just expected more.”

Degrees from prestigious northern universities were not placed in all her children’s hands. But Mrs. Johnson still believes in the ABC dream. Her eyes and ears can’t help but scout for a bright boy or girl in her town with the stamina and wit to work the ABC magic. And from time to time, she recommends a recruit, a real winner, to take that ticket and weather the ride.

“It is a great opportunity,” she said faithfully, “and it takes a certain kind of person to make the best of it.” W

©1993 Charlise Lyles

Charlise Lyles, an ABC graduate, is a reporter for The Virginian-Pilot and Ledger-Star in Norfolk.