SERINGAL CACHOEIRA, BRAZIL–It doesn’t look much like a battlefield. A huddle of wooden huts raised on stilts crowns a grassy knoll. Tidy dirt paths stitch the way between the houses. Lush orange trees dot the hill, throwing deep shadows, and at the crest, a pair of goal-posts marks a makeshift soccer field. Children gambol among grazing cows. Now and again, a pair of macaws takes wing, a startling flash of primary red, blue and yellow against the mottled sky. A hundred yards away the jungle begins, a mat green wall rising to a splendid ten-story canopy. A visit to the Cachoeira Extractive Reserve is like walking into some tropical idyll, or a painting by the younger Breughel, as Claude Levi-Strauss once described the Amazon, where “Paradise is portrayed as a place in which plants, animals, and human beings live together in tender intimacy.”

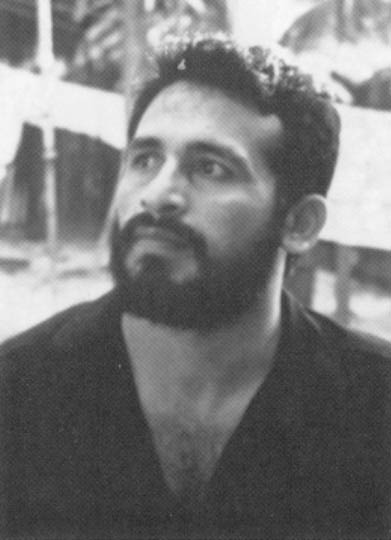

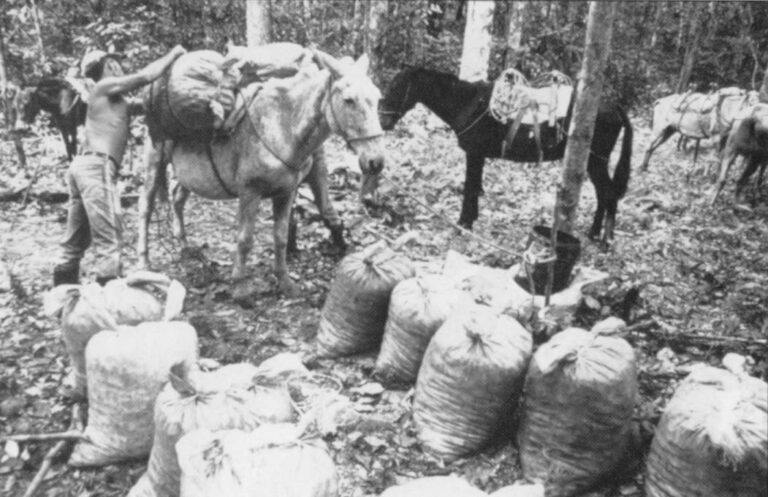

Yet it was here, in the western Brazilian state of Acre, near the Bolivian border, that Amazonian labor leader Francisco Alves “Chico” Mendes Filho and the rubber tappers made their stand. Early in 1988, a local rancher, Darly Alves da Silva bought out one rubber tapper’s lot, pressured others to sell out as well, and proceeded to deforest. Mendes organized an “empate,” a standoff, mustering “seringueiros,” or rubber tappers, to stand in the way of the rancher’s forest clearing crews.

For a decade, seringueiros had increasingly resorted to empates to halt deforestation. Ranchers and small landholders had already slashed and burned their way through 161,000 square miles of Amazon rain forest, and were steadily advancing on Acre. The standoff at Cachoeira would be Mendes’ last. That same year, three nights before Christmas, he was gunned down as he stepped out his back door. Silva and his son, Darci Pereira, were arrested and charged in the murder. In an important test case last June, Darci Pereira and his half-brother, Oloci, were condemned to 12 years imprisonment for shooting into a crowd of seringueiros last year. But at this writing, 20 months after the Mendes slaying, his accused murderers have yet to stand trial.

That brutal murder not only eliminated one of Brazil’s most eloquent union leaders but also put in peril a vast and still largely untouched part of Amazonia. It also set off a chain of events that would reach around the world and profoundly change the politics and economy of this country’s troubled frontier.

For ever since Mendes’ death, the seringueiros he championed have become something of an international cause celebre. Eleven Hollywood movie producers placed bids for film rights to the Chico Mendes story. Ecologists have decorated them with awards and summoned them to the halls of Congress, Parliament and the Bundestag. Osmarino Amancio Rodrigues, Mendes’ successor, has traversed the globe on speaking tours. Almost monthly, Europeans and Americans call on tiny Xapuri, the sleepy river town where Mendes lived. Mendes has been compared to Gandhi and his name adorns T-shirts, parks, plazas and foundations. Now help from abroad–loans, outright grants, vehicles, technology, and consultants–is overflowing.

In homage to Mendes (and under heat from the world environmental movement) the Brazilian government recently set aside more than six million acres of “extractive reserves,” vast, protected areas like Cachoeira, dedicated to the collection of natural forest products, such as rubber, nuts, and fruits. Just one of them, the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve, sprawls over 2.4 million acres, three times the size of Rhode Island. Late last June, Brasilia announced plans to demarcate another 63,550,000 acres of reserves, an area larger than West Germany.

Rubber tappers, who had next to nothing, now have exclusive claim to these reserves, which enjoy a legal status similar to that of Indian reservations. They do not own the land, but have guaranteed “usufruct,” or land use rights, for renewable thirty-year periods. In a country where land reform has never gotten off the ground, this is hardly a modest achievement.

There is nothing new about this sort of system, of course. Back in Eden, when life was easy, man had only to pluck his sustenance from a bounteous natural garden. That was Paradise. Today, in the argot of the environmental movement, it might be called the first extractive reserve. Since the Fall, of course, things have not been so simple. Exile to the wilderness meant an endless contest with nature, and the mandate of civilizations hence has always been to evolve from the simple economies of gathering to those of cultivation.

That mandate generated fabulous harvests, inventions, and eventually empires, but it spelled the end of environmental innocence, as well. “Divide and multiply and replenish the earth and subdue it,” instructs Genesis (1:28). “I have made thee as a new thrashing wain, with teeth like a saw; thou shalt thrash the mountains and break them into pieces; thou shalt make the hills as chaff,” says Isaiah (41:16).

For the last 10,000 years, settler civilization has been complying with scripture, often to a fault. “Originally, all plants and foods were extracted from the forest,” said Alfredo Homma, an agronomist at the Brazilian research center, Embrapa. Homma has devoted 15 years to the study of extractive economies. “One by one, they were replaced by domesticated plants. At the time, man was not interested in profit but in the imperative of feeding a growing population.”

Now, on the eve of the 11th millennium of agriculture, extractivism is suddenly back in vogue. Society, reeling perhaps before the ruin of a manhandled environment, has soured on the miracles of industry, and turned instead to a gentler, more ecological past. Nowhere is this movement more evident than in the Brazilian Amazon region. A recent trip to Acre’s Cachoeira reserve illustrated just how difficult it is reinventing Eden.

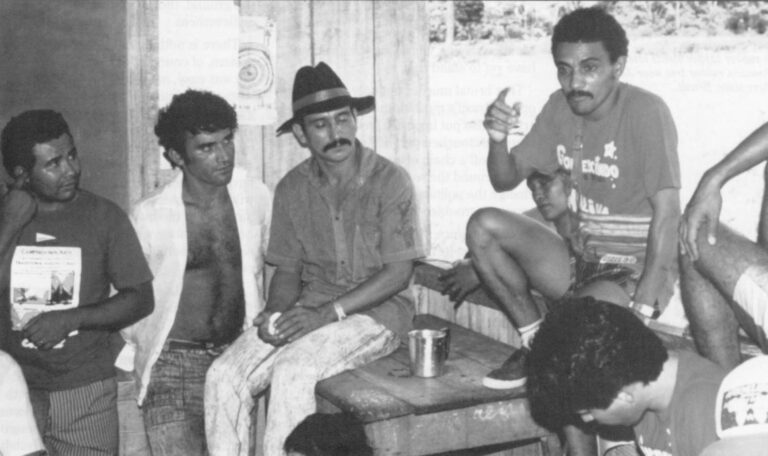

I visited Cachoeira on a Sunday, a rare day of rest for the seringueiros. Women tended to wood-burning stoves while the men lay about in hammocks or chatted in the shade. That afternoon there would be a soccer match. But before the game, there was business to tend to. Some thirty members of the Xapuri producers coop filed into a three room schoolhouse. Grown men in straw hats and rubber sandals sat at school desks before a green chalkboard, waiting to tell about their work and problems. The topics seemed unremarkable stuff. accounts receivable, prices, credit, and marketing. Yet before, during the days of the “patroes,” the cruel rubber barons who ran Acre for more than a century, this scene would have been inconceivable.

Then, seringueiros sold their nuts and crude rubber to the “seringalista”, the boss, who paid what he felt like and sold them back coffee, sugar, medicine, and ammunition at scalper’s prices. This was debt peonage, Amazon style, in which the seringueiro, merely to survive, worked up immense, and finally unpayable, debts to the barracao, the company store. Enforced by the lash and lariat, this barbarous arrangement shocked Amazon travelers for more than a century. “The seringueiro is the only man who works to enslave himself,” wrote Euclydes da Cunha, a famous Brazilian writer and explorer, in 1903. “The most irrational exploitation of the jungle and of man,” the noted Brazilian agronomist, Felisberto Camargo, called it as late as 1951.

The productive plantations of Maylasia, nurtured from Amazon rubber seedlings, came on stream in 1910 and quickly ended Amazonia’s rubber monopoly. The invasion of ranchers and colonists finished off what was left of the rubber elite. The last of the rubber barons cashed out by the beginning of the 1980s. Rid of their exploiters, tens of thousands of seringueiros, through their unions and cooperatives, are painfully trying to piece back together the system of sale and transport. Most of all, they are learning just what it means to be their own boss.

Fittingly, the assembly got underway with a sort of debtor’s roll call. Each member’s name and personal debit were read aloud. All told, Cachoeira owed the central co-op nearly $10,000 last May. The debtor’s roll loosed a series of pent-up frustrations and tensions. The seringueiros complained of the absence of oxen to haul their nuts. Some reported that their stashes were invaded by rodents or rotting in the pounding rains. Most clearly expected the co-op to front money for transport and purchases at the co-op store, or to come fetch their produce. “How can I pay for goods if all my nuts are in the forest?” asked one exasperated member, nearly trembling.

The litany of complaints droned on, but Francisco Assis Monteiro, the co-op president, was implacable. Perched like a cat in the window sill, Assis calmly lectured austerity. There would be no more free ride. “Everyone,” he said, “is going to have to pay for what he buys, on the spot.” To quell the wave of murmurs, Assis raised a hand and talked about what a co-op means. “I’m not anyone’s patrao,” he said, his voice tightening with emotion. “There are no more bosses. You all,” he panned an index finger around the room, “are the bosses now.” The protests simmered away all morning.

While the seringueiros struggle to make ends meet, the academic debate over extractivism thunders on. The promoters argue that it is the rubber tappers, Indians, and other “peoples of the forest,” who will show the way towards “sustainable development.” In the extractive reserve, economy and ecology are happily wed. Extractivism, they say, could at once retrieve Amazonia from the jaws of disaster and nurture a prospering tropical Arcadia.

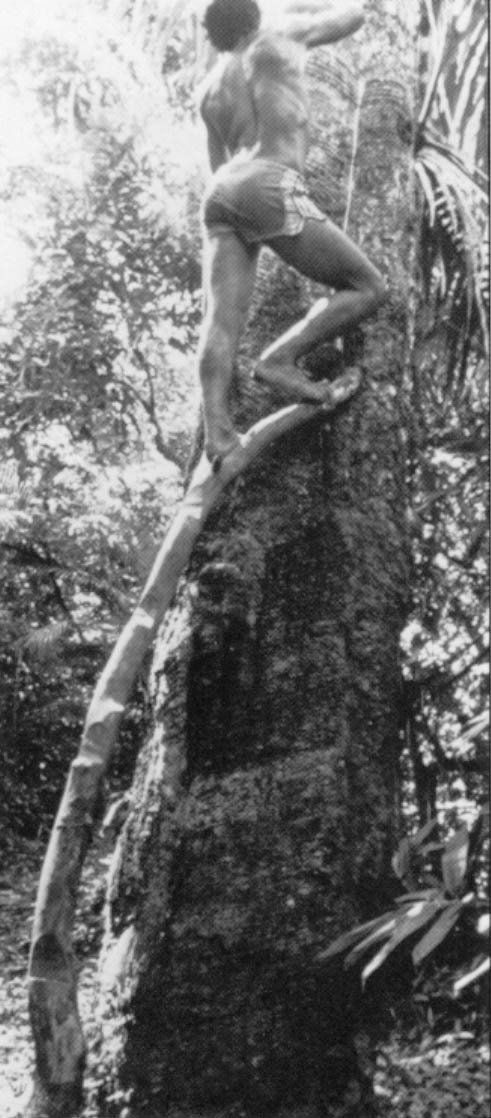

Undoubtedly, extractivism is ecologically sound. The tapper milks the rubber tree of latex and collects fallen Brazil nuts without harming the forest. By contrast in much of Amazonia, cattle ranching and land grabs by small-holders have been not only ecologically destructive but often a waste of money. (Ironically, in Acre, with good soils and few pests, careful pasture management has made ranching profitable.)

But extractivism is also historically fraught with difficulties. “Extractivism is an inherently unstable system,” said Embrapa’s Alfredo Homma. Homma is one of the doubters. He has found that the very success of forest products can provoke the demise of extractivism. For decades, Brazilian forest dwellers collected large quantities of guarana, a native berry containing a high dose of caffeine, for a popular soft drink. Then, in the 1970s, demand for guarana skyrocketed, from 250 to 1600 tons a year, far outstripping the capacity of the extractive economy. “Now,” said Homma, “all guarana is planted.” Likewise, cacao was harvested wild until world chocolate demand spawned a booming agribusiness and put most petty collectors out of business.

There is perhaps no more blatant example of inefficiency than Amazonian rubber extraction. Once the world’s leading producer, Brazil now must import 75 percent of its rubber. Plantations account for nearly half of domestic production and in a few years probably will out-produce the natural rubber groves. Yet extractive rubber survives thanks to an extraordinary subsidy called the Tormb, the Tax for the Organization and Regulation of the Rubber Market. The Tormb is a levy on cheap rubber imported from Asia, meant to protect the costly Amazonian product, traditionally two to three times as expensive.

What is more, companies like Goodyear and Michelin may import rubber only after they purchase a minimum quota of Brazilian rubber. But in a crowning irony, today’s tire makers have little use for this erstwhile “white gold.” Amazonian rubber is shot through with impurities, and serves mostly for lower grade tires and auto parts. Now, the tire companies fulfill their national quotas buying as much as possible from their own plantations, far from the native rubber groves.

“If the Tormb were eliminated, the extractive sector would end tomorrow,” said Paulo Sergio Coelho, a rubber expert at Brazil’s environmental institute, lbama. Coelho favors the Tormb as a support to the embattled seringueiros. The rest of Brazil may not remain so sympathetic, however; for it is the consumer who must finally foot the bill for this archaic economy, paying stiff prices for rubber goods.

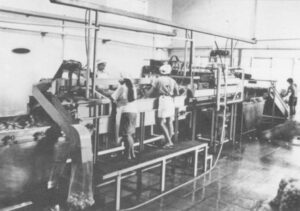

Fortunately, Brazil nuts fetch a far better price in the world market. The seringueiros are now running Xapuri’s first factory for processing nuts, built with a $30,000 loan from Cultural Survival, a Cambridge, Massachusetts-based human rights center. Cultural Survival anthropologist Jason Clay helped negotiate a deal with the Vermont ice cream chain, Ben and Jerry’s Homemade Ice Cream, to buy up Xapuri’s Brazil nuts to mix into its newest flavor, Rain Forest Crunch. The Xapuri factory plans to produce 70 tons this year, which would net about $160,000. But with Cachoeira’s travails, seringueiros will be lucky to process two-thirds that amount.

Academics may extol the forest’s treasures, but the seringueiros have few illusions about their fragile vocation. Most rely on vegetable gardens for subsistence, but virtually their entire cash economy still depends on just two products, rubber and Brazil nuts. Ecologists now speak of “densifying” the reserves, planting cacao, coffee, and other cash crops in the shade of the rubber groves. But so far these are little more than proposals on paper and fledgling experiments in test plots They seem giant steps for communities who are hard pressed to gather, process, and market the products they know.

More discouraging still, 90 percent of Acre’s revenues derive not from any economic activity but transfers from the federal coffers. This state, Brazil’s center piece of extractivism, is constantly operating in the red. “We are looking for help. We’re talking to every kind of ‘ologist’ there is,” said Amancio. “We have to get out from under the tutelage of rubber.” Ronald Polanco, an economist who manages the nut factory and co-op, put it bluntly. “What we are able to do now is administer the misery.”

In fact, the seringueiros have managed much more than that. Mendes’ genius was his ability to parlay world anxieties over global warming and the tear in the ozone into vital aid for a near castaway class of rural laborers. His death sowed doubts and some bitter divisions among seringueiros, but his successors have astutely grasped their special position.

“A few years ago, we didn’t even know what ecology was,” said Amancio one tumultuous evening before a knot of aides and reporters at the National Council of Seringueiros in the Acre capital of Rio Branco. The Brazilian press had been ringing all clay, Amancio had to draft another press release, and Amnesty International was on the phone again. “We thought it was some kind of dessert. But we understood that it pleased people abroad. So we began to talk about ecology.”

Amancio began to pace the cramped Council quarters, working his argument as he walked. “After all, the ranchers had 20 years and millions of dollars in financial incentives, and what did they produce?” No one answered but the question hung in the air, like an echo. Now the seringueiros have the land, funds, technical aid, and the world’s blessings to try things their way. For all the fanfare over the Amazon’s bounty, they know finally that it is up to them–and not Green Parties, government grants, or goodwill from abroad-to make things work.

©1990 Mac Margolis

Mac Margolis, a freelance writer and a special correspondent for Newsweek in Rio de Janeiro, is examining the conquest of the Amazon frontier