TOME-ACU, Brazil–Every evening, when work was done at the farmer’s cooperative, Noburo Sakaguchi would drive home to his small plot of land a few miles out of Tome-Acu, an agricultural village in the eastern Brazilian Amazon region. Sakaguchi, an agronomist by schooling but a woodsman at heart, looked forward to evening when the tedious paper work was done and the searing equatorial sun eased fat and red over the horizon.

He would sit down at the long hardwood kitchen table, take a long belt from a can of Pitu cane liquor, climb into a Caterpillar bulldozer and set out for the forest. Every night for two months he maintained this surly ritual, punishing the jungle with his growling machine. In the end, Sakaguchi had bashed a two kilometer road through the woods. To the innocent observer this might seem just a reprise of the age old story of civilization’s assault on nature, a drama that has claimed woodlands from the Black Forest to Borneo. But Sakaguchi’s road was a really a path to invention.

It would be the main access way through his farm, where, over the next 30 years, he coaxed thousands of trees, bushes, crops and creepers into bloom. You could call it a living emporium. Some 73 species are crowded into his estate of 60 hectares (a hectare is 2.47 acres). The plantation towers with tropical hardwood trees, from mahogany to Brazil nut, and is appointed with exotic fruits like the mangosteen, the size of a lime and stuffed with a subtly sweet pulp, and cupuassu, a dusky relative of cacao. His driveway is shaded by 100-foot andirobas, whose wedge-shaped fruit is boiled down into a quality oil that can be used for cooking or makeup.

Sakaguchi insists that his forest farm is merely the work of a green thumb and an incurable itch to see what can come up on a single patch of Amazonian soil. In Tome-Acu they call it, only half in jest, the Botanical Gardens. For the last three decades, in fact, it has become a veritable biological library, serving as a reference for an entire community of newcomers puzzling out a living on some of the most niggardly lands in the Americas.

Sakaguchi, at 53, is one of the sages of this colony of Japanese immigrants. Their 62-year tenure here has been, predictably, one of suffering and sacrifice. Illness and despair have frequently gutted their number. Lately, inflation and a national economic slump have taken their toll. Yet despite the setbacks, the Japanese and their descendants have not only survived but, in many ways, flourished here. This is no mean feat. Amazonia, after all, is perhaps the meanest region of the Tropics, that forbidding venue for which countless conquistadors and fortune hunters have had, in the words of historian Alfred W. Crosby, “the teeth but not the stomach.”

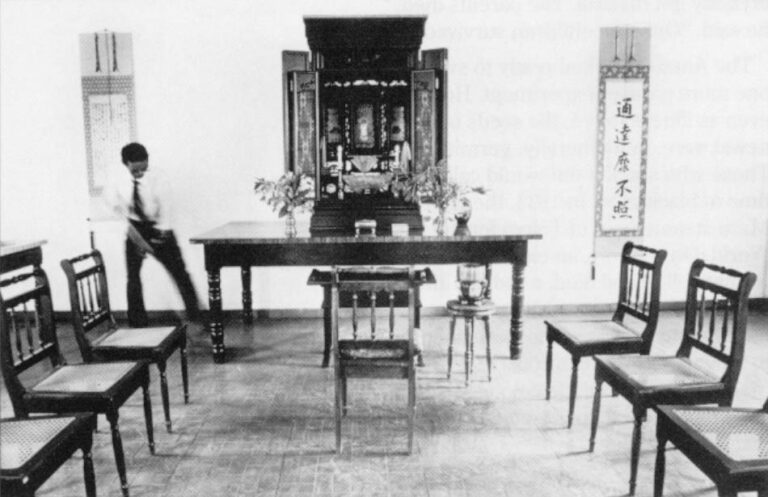

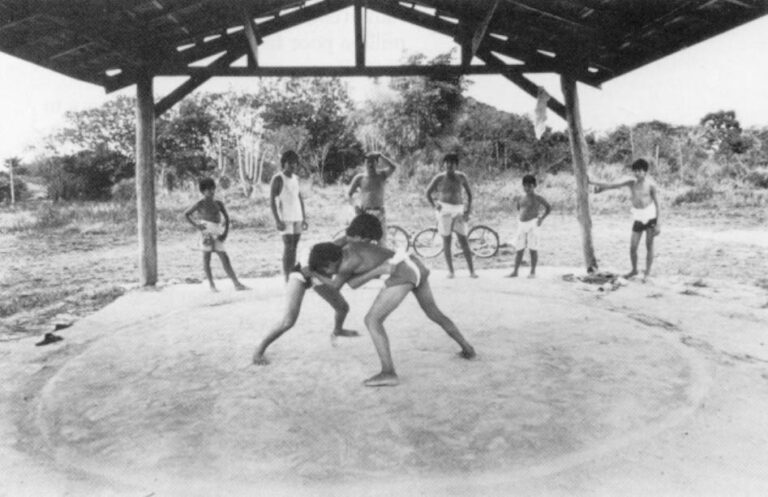

Tome-Acu is, fittingly perhaps, a hybrid of unlikely elements. On a given Sunday, worshippers may choose between the Catholic church, two Buddhist temples, and a host of evangelical churches. Japanese is still the lingua franca here, and even now negotiating Portuguese is a painful exercise for many residents. In restaurants, chopsticks, miso and tofu accompany black beans, manioc, and beef steak, the staples of Brazilian cuisine. Last June, while every Brazilian soul was glued to the television for the soccer World Cup, Tome-Acu was preoccupied with its annual baseball tournament, held at the harvest of the spice pepper crop. The centerpiece of town nightlife is the Karaoke, the Japanese sing-along, where patrons emboldened by whisky or sake belt out Sinatra ballads, Brazilian pop hits, and a wealth of Japanese torchsongs.

This town is the fruit of one of this century’s most remarkable diasporas, which scattered millions of Japanese across the globe in scant decades. Fleeing overcrowding and depression at first, and then the ruins of World War II, poor Japanese poured out of the cramped islands and set out for the empty frontiers of Asia and the New World. One wave of ÈmigrÈs went to Korea, Taiwan and Manchuria. Several more hit Hawaii and the American mainland, until immigration authorities slammed the U.S. borders shut in 1924. Yet another washed up in South America, all the way to the Andean highlands and down to Brazil. Sao Paulo, with a million Japanese, now harbors the largest community outside the home country.

In September 1929, the steamer Montevideo Maru docked at Rio de Janeiro, jammed with Japanese immigrants. Most of the arrivals headed to Sao Paulo and Parana, but 43 families turned north, sailing all the way to Belem, where the Amazon river empties into the Atlantic. They went 130 miles inland, deep in the rainforest, and built farms, schools, homes and hospitals.

By all rights this community ought not exist. For more than a century, the eastern Amazon has been the target of ill-starred official colonization plans. The first was in 1875, not far from here, in the Zona Bragantina, where fifteen “colonies” were founded. The settlers were Italians and Germans, lured by land grants from Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro II. But the distances from farms to the markets in Belem were considerable and the terrain severe. Worse, the Bragantina’s soils were acid when they were not sandy. By 1901, the 70,000 settlers dwindled to only 16,000. “Agricultural colonization by Brazilians in the Amazon left only melancholy memories,” writes historian Roberto Santos.

Recruited by a Tokyo colonization company, Nantaku, which beckoned colonists to a “second Paradise,” the Japanese found instead intractable jungle, distant markets, and endemic disease. But a core of immigrants stuck it out. They founded a pair of villages, Tome-Acu and Quatro Bocas, and began to negotiate a covenant with the new and strange land.

NOBURO SAKAGUCHI’S ROMANCE with the Amazon began thirty years ago. The young graduate had a row with his family in Japan; they wanted him to study law, he wanted to make things grow in the Tropics. His dream then was to go to Cambodia to plant rubber trees, whose milky latex was the raw stuff for the gadgets of the early industrial age: automobiles tires, hermetic seals, weather proofed clothes, surgical gloves, and syringes. “White gold,” they called it at the beginning of the century, “gold that grows on trees.” But by 1960, Southeast Asia was already engulfed in war, so Sakaguchi sailed on to Brazil.

It is one of those little jokes of biology that plants found wild in one place often fare better cultivated on alien soil. So it was with coffee, native to Africa but most successfully planted in South America. The puny maiz of the Andes burgeoned into hardy, giant-eared Kansas corn. Amazonian cacao is routinely ravaged by fungus when planted in its home habitat but thrives in the semi-arid coastal plains of Bahia. Likewise, while Amazon rubber seedlings sprouted all over Maylasia, repeated attempts to plant rubber in its native Amazonia were consistently thwarted by plant disease. Today, biological engineers tinkering with chromosomes, fertilizers, and climate control have managed agricultural marvels. But these are long-term projects. By the time Sakaguchi got to Belem, the rubber boom had long since left the wild rubber groves of the Amazon behind.

The pioneers of Tome-Acu soon fell into the millennial farming practices of the Amazon basin. They felled the jungle, burned off the debris, and planted subsistence crops–rice, beans, manioc, mostly–pressing on when the soils gave out. But they also innovated, introducing radishes, celery, cabbage, and green peppers. But these strangers with their strange new foods failed to win over local palates. “The sight of grumbling Japanese farmers dumping loads of produce in the river at the end of the market day must have seemed even more odd,” wrote Christopher Uhl and Scott Subler, Pennsylvania State University agronomists who have long tracked developments in Tome-Acu.

Then malaria and blackwater fever struck, and soon became epidemic. Satoshi Sawada, one of the community’s pioneers, arrived in Brazil in 1930. Six years later, he buried his mother and his father. In the next decade, Sawada watched 480 families pack up and leave. By 1940, only 40 families remained. “Everybody got malaria. The parents died,” he said. “Only the children survived.”

The Amazon looked ready to swallow one more pioneer experiment. However, even as illness raged, the seeds of renewal were, quite literally, germinating. Those who stuck it out would call this the time of black gold. In 1933, the Hawaii-Maru steamed out of Tokyo for the New World. On the way, an elderly Japanese woman fell ill and died, a sad but all too common occurrence on the arduous month-long passage. The ship detoured to Singapore for the burial. On a whim, Makinosuke Ussui, the colonial recruiting agent, picked up 20 seedlings of Indian spice pepper.

Though virtually unknown in the New World, pepper had long built fabulous fortunes in Europe and the Far East. It was pepper that helped hoist Lisbon, with its bountiful spice colonies, into the status of a world class trader and turned Antwerp into the 16th century’s financial center. The chance acquisition in Singapore not only would change forever the fortunes of this embattled Amazon community, but also write a new entry in the ledger of agriculture in the Americas.

Legend has misted history now; in Tome-Acu they say three pepper plants survived, though some swear it was only two. But these few seedlings were enough to start an agribusiness. Once again farmers cleared their fields, sowed the black pepper, and waited. The results were startling. Every rainy season, this landscape of mottled greens and browns blushed in the glorious red of ripening pepper fruit. By 1956, Tome-Acu’s pepper crop satisfied the Brazilian market and began to export. By the late 1970s, farmers all over Amazonia had caught on and Brazil became the western hemisphere’s leading producer. Malaysia and India growers have since taken the lead, but in 1983, thanks largely to Tome-Acu, Brazil briefly led world pepper exports. “My rubber trees turned into pepper,” Sakaguchi said, loosing a wry laugh.

Hiroshi Muroi, who is 63 and a confessed “lover of pepper”, remembered those times fondly. 1 found him raking over a tarpaulin arranged in neat squares of both black and white pepper, like the dismembered parts of a giant chess board. A sweet perfume of pepper corns drying whole in the sun saturated the air. In the early 1960s, Muroi, formerly a pear farmer in Japan, cleared 25 hectares and planted 5000 pepper seedlings. “The first harvest, I got 600 kilos of pepper,” he recalled. “The second year, I got six tons. The third year, 12 tons. By the fourth,” he smiled, “18 tons.”

Soon Muroi built a home, a roomy, wooden farm house where he still lives. It is a monument to his enterprise. The garden was draped in delicate mosses. Cactuses of all geometries decorated the window sill. Inside, the calls of caged curio and sabia birds mixed riotously against a counterpoint of tinkling Japanese mobiles. A forest of brass trophies for pepper, cacao and dende palm crops had sprouted on his mantle piece.

But the Amazon has never been kind to wonder crops. Henry Ford cleared a vast swath of land the size of Connecticut along the Tapajos river, and planted rubber trees from horizon to horizon. Then came mycrocyclus ulei, a leaf blight, ruining the plantation that was to nurture his motorcar industry. Fungus also struck the pepper plant. But this time, nature played it straight. The black gold of the East fell prey to the ills of its new, foreign habitat.

Sakaguchi explained. In Amazonia, he said, where hundreds of species coexist in a single hectare, this tremendous “bio-diversity” acts as a protective shield. The myriad species, each with a different genetic makeup, form a natural barrier, isolating the funguses and microbes that abound in the hothouse of the jungle. A monocrop, by contrast, is a sitting duck for disease. “I am Sakaguchi,” he thumped his chest. “If there are thousands of Sakaguchis, one right next to the other, and one gets the grippe,” he now grabbed his throat, “every Sakaguchi will get the grippe.”

The grippe this time was called fusarium; it attacked the vine at the root and wouldn’t let go. Plants that normally bear fruit for up to 15 years now live for only five, barely enough time for a farmer to earn back what he invested. The root blight first appeared in 1957, and in 15 years it had romped all over the eastern Amazon.

Once again, Tome-Acu hunkered down for a crisis. To compensate for losses, farmers planted more and more pepper. For their efforts they reaped successive bumper crops but also a price collapse due to oversupply. The only solution for Tome-Acu was to intensify planting on existing plots and to diversify. Few families gave up on pepper completely, but now they wanted to hedge their bets. Much of the inspiration came from the Botanical Garden.

Sakaguchi, mulling over the dilemma in Tome-Acu, came to the conclusion that Amazon farming practices had to be stood on their head. “In agricultural school we were taught to pay attention to the soil. Prepare the soil and you will get a big harvest,” he nodded. “Very modern. Very wrong.”

In the Amazon, however, “the nutrients are above ground. The soil is very poor. The fertility is in the vegetation,” he continued. “It’s in the trees. They control light, humidity, and protect the soil. In Amazonia you have to take care of the trees.”

So the farmers of Tome-Acu began to redesign their plots, not as unichrome carpets of single crops but as a mosaic, imitating the diversity of the rainforest around them. Soon Tome-Acu was a dappled quilt of “polycultures”. As many as ten to 25 crops are now planted in “consortium”, where Brazil nut or rubber trees shade cocoa, and seasonal crops are sown in the alleys between passion fruit or pepper vines. To the untrained eye, a 20-hectare plot, an average farm in Tome-Acu, looks nearly like a patch of virgin forest.

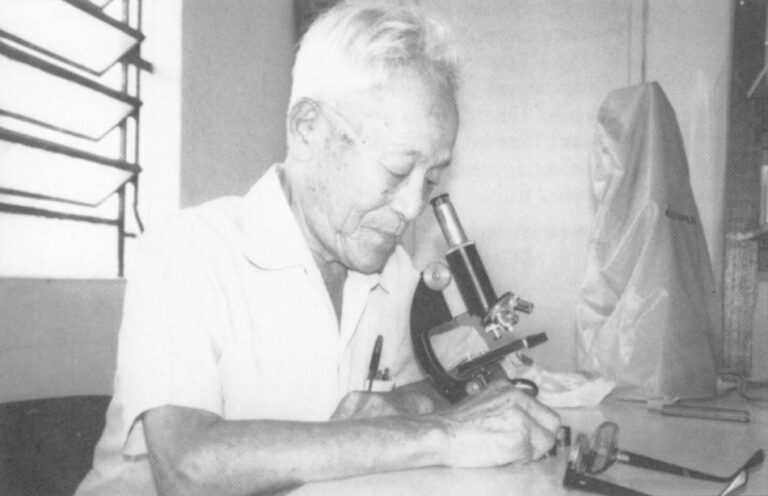

Most important, the Japanese settlers all but dispensed with beans, rice, and corn, crops which are prey to the vagaries of local markets and hard on the poor Amazonian soils, forcing farmers to deforest ever larger areas. Now, they concentrate instead on rarer items, such as exotic fruits, with secure markets at home and abroad, and handsomer prices. “Everywhere we went we noticed people were interested in tropical fruits,” said Toshitsugu Kuhayakawa, Tome-Acu’s botanist. Kuhayakawa is 75, a fragile, white-haired man with large horn rim glasses and an easy laugh that splinters his face into a million lines. Kuhayakawa spent years in Taiwan experimenting with endless varieties of sweet potato, but he longed to try out his sciences on the complexities of the Amazon. He arrived in Tome-Acu in 1970 and, together with Sakaguchi, began selecting seeds of the best varieties of tropical fruits.

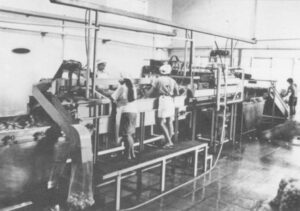

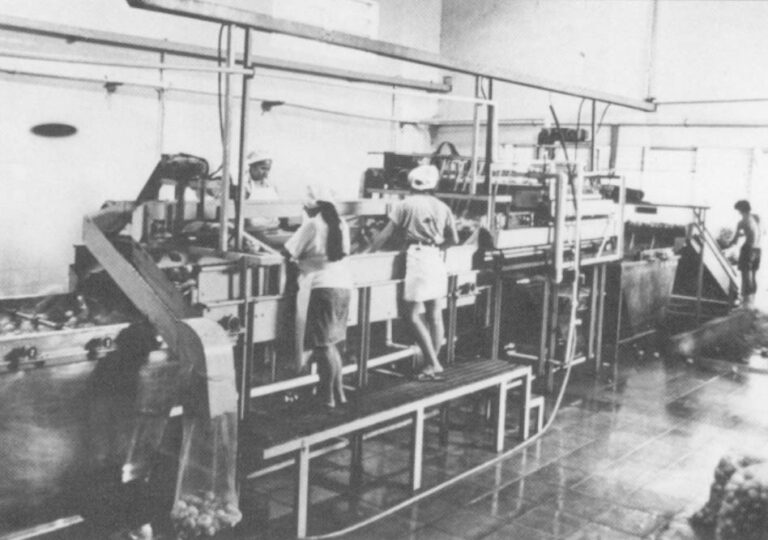

Now the co-op runs a juicing plant, which processes up to 7,000 tons of passion fruit pulp for a juice maker in Sao Paulo. Lately the co-op has begun cultivating more select items, such as cupuassu, with a rich, creamy pulp ideal for juice, jam and ice cream, and a seed that makes a fine chocolate. Another is the acerola, or cherry of the Antilles, a reddish-orange berry that contains 100 times more vitamin C than the equivalent amount of oranges. It can be pulped for juice or freeze dried for vitamin C tablets. Unlike most citrus and food crops the acerola takes well to Amazonia’s acid soils.

In a country where lumbermen almost never bother to replace the forests they’ve logged, a handful of Tome-Acu farmers also began to look ahead. Over the last ten years, Tomio Sasahara has replanted much of his 100 hectare spread with tropical hardwoods. “This is for my children,” he said, tramping around his own manmade forest, pointing to strapping stands of Mahogany, Rosewood, Cedar, Brazil Nut and Jacaranda- some of the most precious timbers in the world market.

DAUNTING OBSTACLES STILL lie ahead for Tome-Acu. All over Brazil, in fact, another tropical blight, perhaps the worst, has set in; endemic inflation. Despite president Fernando Collor de Mello’s “life and death battle” with the beast, inflation rose a startling 1,800 percent in 1990. The result has been soaring fertilizer costs, a steady erosion in the value of farm products, and a drought of subsidized credit. Worse, in a sort of shotgun wedding of economy and ecology, the debt-strapped government in Brasilia simply cancelled credits for farming above the 12th parallel, the southern edge of Amazonia. The measure may brake the advance of agriculture in the rainforest, but it also abandons half a million poor farmers to their own meager devices.

As a result, Tome-Acu has begun to suffer the same syndrome that assails rural communities the world over, an exodus of young people and an inexorably aging population. The farmer’s co-op, which once had 350 members, is down to 150. Some 300 families have sent sons and daughters to Japan in search of cash and jobs, thus reversing the journey their grandparents made 60 years ago.

“None of my children want to come back to Tome-Acu,” said Ryoji Funaki, director of the co-op. Between strenuous drags on a cigarette, he recited the litany of problems in the countryside. “No electricity, no schools, poor health, no security, no nothing.” His nervous gestures left a web of smoke trails. “No one wants to come back here.”

CHRIS UHL SMILED when asked about Tome-Acu. “I sometimes think it’s the final proof that agriculture is impossible in the Amazon,” he told me on a recent afternoon. Uhl, who is based in Belem, has spent much of the last decade searching for the chimera of “sustainable agriculture.” Put oversimply, that means farmers who don’t farm their lands to death. Too often, he has seen the Amazonian smallholder, locked, like some backlands Sisyphus, into an endless cycle of slash-and-burn farming on ever more impoverished fields.

Indeed, for all their ingenuity, the farmers of Tome-Acu may not be so much an example for Amazonia as an anomaly. Unlike their Brazilian neighbors, they have been blessed at times with aid and credit from abroad. They have also relied in the past on high doses of fertilizers, both chemical and organic, costly inputs that are unthinkable for the average Brazilian smallholder. “If the Japanese, with all their talent and resources, are still barely getting along, what hope is there for the far poorer and scattered farmers of the Amazon”.

The question required no answer, of course, but Uhl’s own research betrays a clandestine optimism. In the Amazon, he has commented, virtually all colonists are aliens and there are no privileged castes. Nor, one might add, is there any deus ex machina poised to pluck foundering settlers from disaster. It is rather the glue of a common culture that has helped bind this community together through countless crises. What is more, while many farmer’s associations in the Amazon have folded, Tome-Acu has fought to maintain a cooperative, which has been running in various incarnations since 1931. The co-op provides members a vital network of financing, markets, and, most importantly, information. The successes here owe less to beneficence from abroad than to solidarity and sheer doggedness. “The only way is to try, and try, and try and make mistakes and try again,” said Kuhayakawa, hunched over a microscope and a collection of petri dishes. “Mostly, we have been on our own.”

The example of Tome-Acu, Uhl and Subler have written, “provides the hope that perhaps someday man can reside in harmony with nature.” That may seem pale encouragement for immigrants who crossed the oceans to make a new life half a century ago. But if the farmers of Tome-Acu were to fold up and decamp tomorrow, that legacy alone would be nothing less than monumental.

It may not be any one crop or technique, finally, by which they help solve the riddle of this land, for the Amazon has played havoc with virtually everything the farmers of Tome-Acu have tried. Rather, it is in their ability to read and adapt to the land and its requirements. Just as their forbears withstood war, famine, overpopulation and a shattered economy, at each crisis, the people of Tome-Acu–pioneers, nissei, and sansei alike–have reached deep into the well of cultural experience, and, again and again, come up with a response.

MY LAST EVENING in the village, Sakaguchi took me on a lengthy tour of the Botanical Garden. Later, over a savory dinner of roasted fish and spiced eggplant, irrigated by generous closes of Pitu, he spoke at length about the rules of tropical agriculture. Farmers everywhere like to jawbone about the weather or prices or prospects for the next harvest. Sakaguchi talked about the future. “Am I rich?” he shrugged. “No. Right now, I don’t earn anything from this,” he gestured into the night towards his gardens. “Fifty years from now I won’t be here, but these trees will.” Suddenly he went silent and sat now nearly motionless, puffing on a cigarette fixed onto a long metal pipe stem, lost in private thoughts and a veil of white smoke.

I ran into Sakaguchi a last time on the bus back to Belem the next day. He was dressed in pressed shirt and trousers; on top was a tidy plaid sports cap. He smiled broadly and said he was headed to the Dominican Republic, the Caribbean island nation, for a two-month consulting job. There, too, a wave of Japanese immigrants had fallen ashore, and now another colony was in need of counsel. Sakaguchi smiled again, contented, I imagined, with his new mission. Then he pulled the lid of his cap over his eyes and, in the sort of miracle managed only by those inured to the punishing landscapes of the Third World, slept through the entire bone-jarring, four-hour journey to Belem.

As the bus heaved and pounded its way over the dirt top, I couldn’t help but feel that the fate of this Amazonian community turned largely on a special formula: uncanny endurance, the judicious use of a bulldozer, and the forehead that rested under the brim of that plaid sports cap. And maybe, Sakaguchi might add, a dollop or two of Pitu.

©1991 Mac Margolis

Mac Margolis, a freelance writer and a special correspondent for Newsweek in Rio de Janeiro, is examining the conquest of the Amazon frontier.