Editors Note: APF Reporter Vol.11 #3 exsisted only as a photo copy, becuase of this the pictures in this story are of poor quality.

Half a mile from one of the swankiest white neighborhoods in South Africa lies the black township of Alexandra, with 180,000 people crammed into one squalid square mile of mud, shacks and discontent.

Only two and a half years ago, blacks regarded Alexandra as a “liberated zone” and governed the township through “peoples’ courts” and street committees. To fight government forces, township youths built barricades of burned-out vehicles, dug trenches to tip over armored cars and lobbed stones and petrol bombs at soldiers and police. Troops fought back with bullets and tear gas. At one point, white soldiers guarded the entrances of the township. Some stood behind four-foot walls of sandbags while others searched cars entering the black ghetto. Army sharpshooters wearing bullet-proof vests sauntered on the rooftops of the Indian shops at the edge of the township.

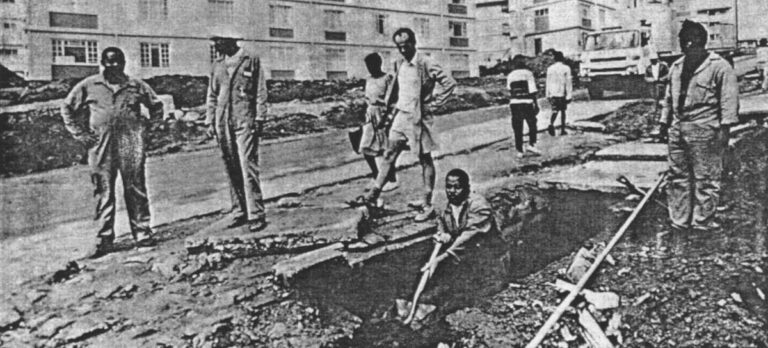

Today, the South African government is trying to transform Alexandra from a monument to apartheid’s cruelty into a showcase for government reform. The roadblocks have been taken away. The government has laid down its guns, packed up its sandbags and taken up shovels. The government is building sewers, handing out cricket bats and constructing new schools and houses, all part of a sophisticated scheme some officials call “WHAM”–winning hearts and minds.

To some, the idea that the white minority government in Pretoria can win the hearts and minds of black South Africans sounds as far-fetched as the proposal in 1890 by a reactionary Russian thinker who suggested that a reformist czar might keep his throne by putting himself at the head of the socialist movement.

Yet in a sense, that is exactly what the South African government is trying to do. Pretoria has singled out 34 of the black townships that were the “hottest” spots for political unrest and has begun to pour money into them. It has taken the lists of grievances articulated by black community activists and started to tend to those grievances–while keeping the revolutionaries under lock and key. One Cabinet minister calls the strategy a combination of a velvet glove and an iron fist.

Alexandra will be a test case of that strategy. From the township near the edge of Johannesburg, a picture emerges of a complete cycle of grievance, uprising and crackdown that has been the story of South Africa’s conflict.

Whether the government can break that cycle remains unclear. The government is pouring $45 million into upgrading Alexandra. At the same time, it is holding a show trial of five leading Alexandra activists, accusing them of treason. While the trial grinds on, the accused are in custody. The trial, which is being monitored by a group of distinguished American jurists, sends a clear warning to anyone hoping to reestablish the opposition’s control over the township.

Reversing the wrongs of apartheid is a mammoth task, as Alexandra shows. Seventy-eight years of bitter history makes the township a fertile place for black resistance. The rectangular piece of land had been a farm around the turn of the century on the outskirts of a tinier Johannesburg. When a widow tried to sell the farm, no whites wanted it. So in 1912, a land development company obtained special permission to sell the areas to blacks, making Alexandra one of the few places in South Africa where blacks had the right to own property.

Black townships nowadays are placed tactfully behind mine dumps or hills, unseen and unnoticed by whites in their sheltered suburbs. However, Alexandra was founded before the white Johannesburg suburbs fanned out to the north. As Johannesburg expanded, Alexandra became an eyesore and threat to the insulated safety of white neighborhoods. So the government forced blacks to move to distant sections of the South Western Townships, an area later known by its acronym, Soweto.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, 24,000 people were forced to move. Others lived under constant threat of forced removal. In 1963, the government abolished freehold rights of 2,000 black property owners as prelude to moving all families to other townships and converting Alexandra into a dormitory township with 20,000 men and women housed in eight, single-sex hostels. The first two hostels were opened in 1972. But blacks kept moving to Alexandra and many old-timers hung on. In 1982, Pretoria relented and allowed the remaining portion of the township to stand.

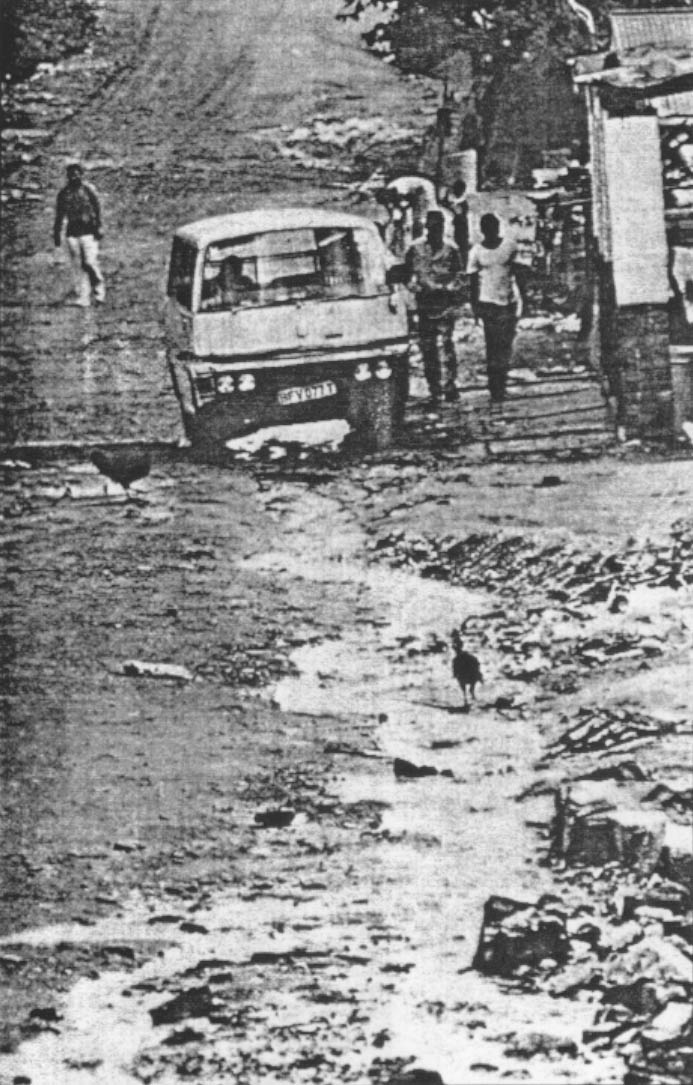

Meanwhile, Alexandra suffered from neglect. Today the township fills a small valley that falls away from a highway that runs from Johannesburg to Pretoria. Its boundaries are plain: on one side, the main road and a row of Indian-owned shops and fast food joints; on a second side, a white residential suburb; on a third side, a handful of small factories with metal cages protecting the windows; on the fourth side, a small creek with a graveyard on the far side. The gutted dirt streets are laid out in a grid. The avenues run from first through 22nd; seven streets named after prominent individuals (including Roosevelt) run perpendicular to the avenues.

The most established members of the community, many of them former freeholders, live in aging brick houses. Each plot holds an average of 15 families living in makeshift houses and cardboard and corrugated metal shacks. Hundreds of people live in five-story single-sex hostels. Blacks migrating from rural areas build new shacks as they pour into the township. Scores of people inhabit the powder blue shells of disused buses parked in a row along one street. Goats and cows roam freely. Residents share communal water taps.

The life of the township takes place in dirt yards and streets. Children run barefoot playing with homemade toys made of twisted clothes hangers. They roll old tires. Adults take recreation in drinking at illegal bars known as shebeens.

Crime is universal. Alexandra has a history of tough criminal gangs. In the 1950s, two rival gangs called the Russians and the Americans were powerful. Modern versions include the Scorpion gang, named for a Scorpion pistol, and the Amakabasa, one of whose members posed for a local magazine while perched on top of a stolen BMW. One local kingpin lives in a new apartment complex with records stacked to the ceiling next to his expensive stereo equipment. Half a dozen of his cohorts hang around his door all the time.

The most embittering aspect of Alexandra is its startling contrast with Sandton, the white neighborhood just across the highway.

Established in 1969, Sandton is a tribute to the golden age of white South Africa. White South Africans have spent hundreds of millions of dollars to convert it from farmland into a rich suburb. Sandton’s winding streets are lined with rambling mansions with high walls and manicured lawns. BMWs and Mercedes automobiles are as common as mailboxes.

Sandton has every convenience imaginable. At Sandton Center, a luxury high-rise hotel and shopping mall, whites shop at stores similar to those found on Madison Avenue in New York: jewelry, clothing stores, hair salons, African art. The center also has a cinema, restaurants, and a popular night club marked by a yellow neon sign. The new suburb has plush offices of advertising agencies and corporations escaping the inner city. The area is dotted with tennis courts and swimming pools.

The discrepancy in living standards has been built into the budget and machinery of apartheid. Though the adjacent communities could have been part of the same municipality sharing common services, Sandton has its own government that lavished privileges on whites while ignoring the needs of its black neighbors.

Consider a handful of official statistics.

Budget.

The budget of Sandton totaled R70.3 million in 1986-87 for a population of just 65,000 whites and about 30,000 black domestic workers, (One South African rand equals about 40 to 50 U.S. cents). That comes to R740 per capita, or about $350. The Alexandra budget totaled R20 million for an official population of 120,000, a figure that excluded an estimated 60,000 people living there in violation of restrictions against blacks living in urban areas. The Alexandra budget comes to R111 per capita, or about $50.

Water.

Sandton had 17,720 domestic water connections on June 30, 1995 and 800 fire connections. In Alexandra, 98.5% of the population shared communal water taps. Usually about 15 families shared each tap. Because there were no drainage facilities around the taps, they tended to turn into mud baths. There were no fire connections.Sewers.

White Sandton maintains 550 miles of sewers and built 11.75 miles of new sewers. Everyone in Sandton enjoys a flush toilet. In Alexandra, there are virtually no sewers. Only 550 people out of a township of about 180,000 possess flush toilets. Residents dispose of feces in buckets, which often go uncollected. In those instances, residents usually dump the buckets into open trenches that serve as public sewers. I once saw a young child fall into one such trench during a rainstorm and nearly drown before being fished out by another child.These poor sanitary conditions were blamed for a 1986 outbreak of polio, a disease that has been wiped out in most of the third world.

In addition to reversing years of economic neglect, the government is trying to defuse political activism. The depth of that activism emerges from documents filed in the treason trial now underway.

On February 5, 1986, residents of Alexandra gathered at a clearing that had been rechristened Freedom Park to discuss how to build a network of street committees to govern themselves. Fed up with neglect, crime, unrest and official authorities, Alexandra wanted to take control of its own affairs. At the base of tile pyramid of self-government was the yard committee, based on plots shared by about 15 families. “The people of the yard should come together, forget about their tribal differences, classes and their education and form a yard committee,” the minutes said.

Two representatives from each yard would attend meetings of block committees, the next step in the pyramid. Each block committee elected a chairman, secretary and treasurer. Each block committee in turn elected four representatives to attend street committee meetings, organized along the 22 numbered avenues running across the township.

Each of the street committees in turn elected two representatives to “the Supreme Body,” a 44-person executive committee known as the Alexandra Action Committee and headed by Moses Mayekiso, a local resident and general secretary of the Metal and Allied Workers Union.

The activists of Alexandra set high standards and strict guidelines for people participating in the committees. “What is expected from a rep?” a memo of the Alexandra Action Committee asked.

- A rep must be well disciplined, devoted and loyal to the people whom he/she represents.

- He must be in a position to listen to what the people want and must share ideas with them.

- A rep has no chance to dictate since he is elected by the people.

The documents of the Alexandra Action Committee reflect the pressing concerns of the community, concerns that hadn’t been addressed by government at any level. The AAC identified the problems as unemployment, harassment by Police and police informers, high taxi and bus fares, low wages, high rents, poor education, poor housing, the demolition of shacks by police, the presence of troops in the townships, and the “bucket system” of sewerage. Mayekiso talked about starting cooperatives for the unemployed and bulk buying schemes to reduce the price of goods. “We want people to help each other,” he said.

The action committee heard complaints against businesses and drew up a selective list of stores for Alexandra residents to boycott. On April 21, consumer boycotts went into effect against fifteen different establishments, ranging from a large retail chain–Jazz Stores–to community councilors’ businesses and two shebeens in the townships.

The action committee also changed street names. Instead of names like Roosevelt and Hofmeyer, they rechristened streets after MK (short for the ANC military wing Umkonto we Sizwe), Steve Biko, Nelson Mandela, Joe Slovo (South African Communist Party chief), Robert Sobukwe (the late leader of the Pan African Congress), Bazooka and ANC president Oliver Tambo.

The local street committees also functioned as “peoples’ courts.” Mayekiso explained that “people were tired of taking problems to the police.” By April, the action committee was dealing with four to five cases a day, he said, ranging from settling marital problems to prosecuting “tsotsis” or gangsters. “The committee can mete out punishment and judgment” Mayekiso said, but he was fuzzy about the punishments meted out. “We are against harsh punishments of other townships where people are burned. We don’t want to be like the police. We want to create unity.”

Alexandra’s activists were so confident that they had created a liberated zone that they kept detailed records of street committee cases, records later presented by the state as evidence in a treason trial against Mayekiso and others. In one month, the seventh avenue street committee, sitting under a tree in a fenced-in yard, heard at least 26 cases, including four charges of assault, four domestic disputes, a complaint about the retrenchment of employees, three charges of theft, three of attempted murder, one house breaking, one of “bewitching” and practicing witch-craft, one of “supporting tribalism and being bossy,” and several others.

In two months, the street committee at 19th Avenue heard at least 169 cases, including 21 cases of theft (ranging from a stolen bicycle to housebreaking), 27 cases of assault, and 30 domestic disputes ranging from a husband leaving the house for another woman to problems disciplining children to a disagreement over lobola, the bride price. The committee at 19th Avenue also heard cases that were more explicitly political. One young woman was accused of running away from her boyfriend and “bad talk about the comrades.” One person was charged with “not cooperating with a stayaway.” Two were accused of “working with the system,” one of “being a sellout” and another of “selling out to the police.” But there also were indications that the committees could be used to curb the comrades. One case was brought over a “threat of burning.”

In the middle of 1986, the South African government struck back. With the imposition of a state of emergency and the detention of dozens of activists, open political activity ended. Anyone vaguely suspected of political activity was detained. Mistaking memos from the Alexandra Arts Center (AAC) for Alexandra Action Committee (also AAC), police arrested a butcher, who kept a piano in his butcher’s shop so he could practice when business was slow.

The government also launched its economic offensive. The government has erected a couple of dozen new houses in the worst neighborhood of the township near 22nd Street. Workmen have erected three new primary schools, several prefabricated apartment blocks and a children’s recreation area across the creek, where the only previous construction was an old leprosy clinic. A couple of streets have been paved and a new sewer is being laid on Roosevelt Avenue. Some black adults have been employed in these construction projects. Schoolchildren are being taught cricket to keep them out of trouble and kids run around with team T-shirts and bats.

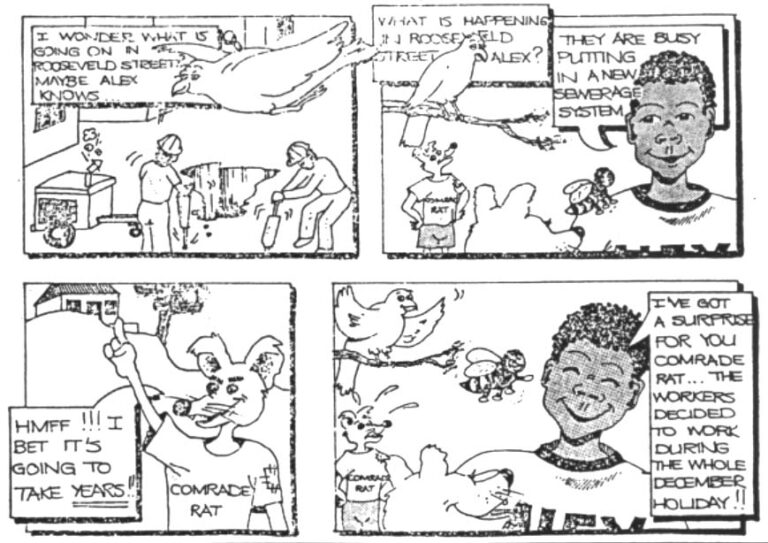

In early 1987, soldiers were handing out a comic strip explaining the government’s efforts. On the cover of the comic, a smiling black boy with the name “Alex” on his shirt was depicted with a smiling dog, a smiling bumble bee and a smiling bird. “Alex and Friends” was the title of the comic. On the reverse side, the bird cooed, “I wonder what is going on in Roosevelt (sic) street. Maybe Alex knows.” Alex explained in the next panel that “they are busy putting in a new sewerage system.” Just then, a scrawny little creature who wore a shirt labeled “comrade rat” chimed in that “Hmff!!! I bet it’s going to take years!!” Alex responded that “I’ve got a surprise for you comrade rat…” and he explained that construction would continue through the holidays and that the sewer would provide a third of the houses in Alexandra with flush toilets. Without promising when the project would be finished, the smiling Alex said another two sewerage systems were planned for the future.

Whether the government will win any friends in Alexandra remains to be seen. The size of the black voter turnout during elections for local authorities in October will be the first indication of whether the government is winning any legitimacy.

Regardless of the results, the government is likely to continue to wage its economic campaign for hearts and minds. “Drastic action must be taken to eliminate the underlying social and economic factors which have caused unhappiness in the population,” Major General Bert Wandrage of the South African Police Riot Unit, said recently. “The only way to render the enemy powerless is to nip the revolution in the bud by ensuring there is no fertile soil in which the seeds of revolution can germinate.”

In a booklet recently circulated among state security officials, functionaries were advised that “a governing power can defeat any revolutionary movement if it adapts the revolutionary strategy and principles and applies them in reverse.”

Opposition leaders doubt the government can reverse the history of apartheid and restore its tarnished image. United Democratic Front leader Murphy Morobe, in an interview given a month before his own detention in 1987, said, “Whites, after suppressing our people for 100 or 150 years, say here’s all the manna you need and we have to say ‘Lord, Lord’ to them. No. They take our people for granted and think they know what’s right. They think better roads will lead to an element of conservatism. But not here where the basic issue of political power isn’t addressed. Peoples’ thoughts have gone beyond better roads and better houses. The main question is who rules and how whoever rules does the governing.”

©1988 Steven Mufson

Steven Mufson, a freelance writer, is reporting on black political leadership in South Africa,