SAIGON, South Vietnam, mid-1963–Mal Browne drifted into a far world, caught up in the aromatic lure of incense, the shadowy vision of shuffling saffron, and the lulling monotone of an ancient prayer.

“Na…Mo…Ah…Di…Da…Phat…” a lean and ascetic monk intoned. A second bonze solemnly drummed a gourd in hypnotic rhythm with the prayer. Browne had come alone to the small pagoda on Phan Dinh Phung Street early on a muggy June morning in 1963. Now he sat next to a gilded statue of Buddha as the monk, serene in his flowing saffron robes, led the incantation for an enrapt congregation of nuns and fellow monks. For an hour the mind-numbing prayer continued, the eyes of faithful and outsider alike glazing as its tempo slowly rose. Then, at 9 o’clock, the ritual abruptly stopped.

Browne, the lone-wolf correspondent for the Associated Press, shook his head to clear it. He checked the cheap Minolta camera New York finally had sent him to replace his battered old Richo reflex and quickly followed the Buddhists out into the street.

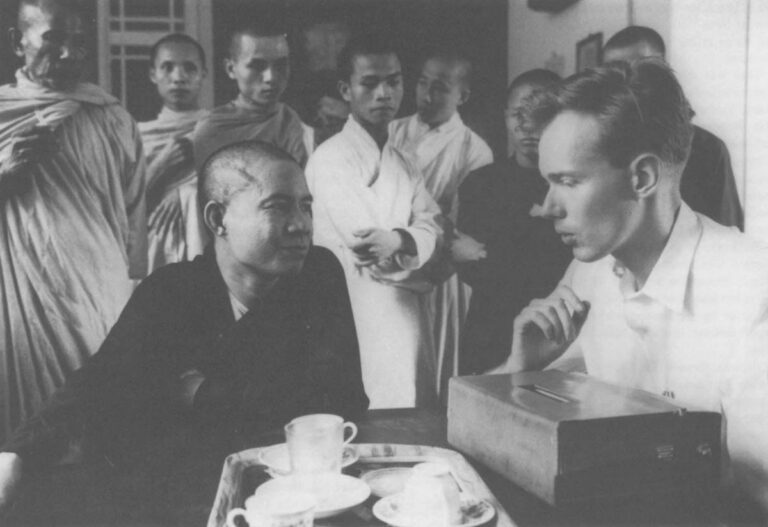

This was not the first time Browne–or other Saigon correspondents–had been tipped off to a protest march in South Vietnam’s month-old Buddhist crisis. But he was the only Western reporter who showed this morning. As usual, the protesters marched in two phalanxes, unfurling signs in both Vietnamese and English condemning America’s puppet government of Ngo Dinh Diem. At the head of the procession four monks rode in a gray four-door sedan. Browne became immediately alert. Riding in Western automobiles was sharply out of character for stoical bonzes.

Suddenly. at a busy downtown intersection, the procession stopped. One monk opened the hood of the car and withdrew a plastic, five-gallon container of pink gasoline. The others led the oldest and most venerable monk, Thich Quang Duc, to the center of the intersection where he seated himself on a small brown cushion, his hands folded in prayer, his legs crossed in a lotus.

Browne focused his Minolta from the edge of the crowd twenty feet away. The camera captured Quang Duc as the gasoline was poured over his shaved head. It clicked as the silent old monk calmly lighted a match and burst into flames. Frame after frame, it methodically recorded the self-immolation of this strange new Buddhist saint, who sat unmoving for five minutes before his charred body finally toppled over. The Minolta also recorded the beginning of the toppling of the Diem regime.

Mal Browne’s ghoulishly dramatic photos of the burning bonze swept across the world’s front pages. The photos seemed everywhere, and everywhere they seemed to symbolize what was wrong with American involvement, if not in Vietnam, at least with Ngo Dinh Diem. In Europe the photos were hawked on backstreets along with pornographic postcards. American clergyman reprinted them in full-page New York Times and Washington Post advertisements proclaiming, “We, Too, Protest.” China distributed millions of copies throughout Asia and Africa as evidence of “U.S. imperialism.” An American official, preparing for a Vietnam tour, noticed one resting prominently on President John F. Kennedy’s Oval Office desk.

The sudden emergence of this new crisis caught everyone by surprise. Although nominally seventy percent Buddhist, only a small minority of the South Vietnamese practiced the faith and most of them in an aberrational form deeply influenced over the centuries by Confucianism, Taoism, animism, and other obscure Asian religions remote to Western thinking. At first, the reporters knew few Buddhist leaders and even less about what they were up to. At the American Embassy a single Buddhist scholar lectured occasionally to small crowds about the Eightfold Noble Path, Greater Vehicles, and Nirvanna–mainline Buddhist precepts more applicable in Thailand or Japan than Vietnam. Diem and his family, who practiced a kind of fundamentalist Asian Catholicism brought in originally by French missionaries, seemed equally at a loss. Diem predictably responded that Browne had been bribed and Quang Duc had been drugged. But just as predictably, Diem had brought most of the trouble down on himself.

The Buddhist crisis had begun almost inadvertently four hundred miles to the north in the ancient city of Hue. If Vietnamese Buddhism had a cultural and religious center, it lay in the beautiful old imperial capital on the banks of the Perfume River. Hue also happened to be Diem’s birthplace, and two of his brothers controlled the city, one as a virtual warlord, the other as the Catholic archbishop. In early May he attended the twenty-fifth anniversary of the archbishop’s elevation to the Catholic hierarchy. Vatican and national flags flew side by side in technical but symbolic violation of Vietnamese law, and several days later, on the 2,587th anniversary of Buddha’s birthday, Hue’s Buddhist community attempted to fly its own five-colored flag. Now the government said no, and the rejection ignited an angry street demonstration. Nervous government troops fired grenades into the crowd, killing one woman and eight children. They also magically transformed the usually passive and unworldly Buddhists into a major and fatal political force.

In the countryside the war against the Viet Cong insurgents had drawn to a virtual halt with Diem’s disconcerting reluctance to commit his government troops to battle. Now a different kind of war began in the cities. It was as if a premature and foreign version of the chaotic Sixties had begun in microcosm in Vietnam: Civil-rights protests, student demonstrations, riots in the streets. With mysterious tips arriving almost daily, the American news correspondents shifted from the jungles and the paddies to the streets, chasing from demonstration to saffron-robed demonstration.

Even so, after a month of marches, the story began to grow stale. It was only a compulsive fear of being scooped that took Browne to the little pagoda on Phan Dinh Phung Street on June 11. The methodical AP man’s photo seemed to convert Quang Duc’s bizarrely symbolic act into an insane infection. In Saigon the teen-age son of an American official tried to imitate the old monk, survived with serious burns, and said afterward he just wanted to see what it felt like. In Washington a youth burned himself to death on the steps of the Pentagon. In the next few months six more monks and nuns committed fiery suicides throughout Vietnam. No reporter passed up another Buddhist tip. David Halberstam of the New York Times, who would share the 1963 Pulitzer Prize with Browne, described a later immolation attended by most of his colleagues: “Thirty minutes passed and we had just about decided to bug out when a man burst into flames. I shall not describe that scene in any detail. Watching a human being burn himself to death gives a man a helpless feeling and a reporter a rare confusion of personal emotion…Well, we covered it.”

The bonzes, few of whom had any real sense of the complex earthly world beyond their pagodas, became remarkably proficient at orchestrating the press. Black-market mimeograph machines churned out press releases in broken English. Protest signs were written in English for the American cameras, an insight into the power that film eventually would have in Vietnam–and the way it could be manipulated. But no one was quite sure what the story meant. Was it religious? Political? Both? Or as inscrutably aberrational as the religion the monks practiced? In the midst of the suicides and growing conflict one bonze, a rarity with an American education from Yale, dumbfounded a correspondent, also a Yalie, by greeting him: “Boola, boola.”

As the crisis worsened, both the South Vietnamese and the American governments suspected a communist plot. None was ever found. The basically nonpolitical Buddhists had stumbled onto a latent and angry anti-Diem nationalism, and Diem stumbled into feeding it. The Americans tried to force their now-embarrassing client to compromise. But he wouldn’t budge, continuing to brand the protesters as communists and the American reporters as collaborators. Never to be outdone, the regime’s outspoken “dragon lady,” Madame Nhu, clapped her hands in glee at the “Buddhist barbecue” and told reporters that, if Halberstam wanted to try it next, she would provide the match. The demonstrations spread to Saigon’s students, government violence escalated, and the spin on the news stories shifted swiftly from religious protest to political crisis to Saigon intrigue and rampant rumors of a coup d’etat. By late June the crisis had grown to the point where Halberstam and Neil Sheehan of UPI agreed to be “kidnapped” by dissident young Vietnamese military officers so they could safely cover the group’s coup from a secret headquarters. The revolt never came off. But the plotting continued unabated.

Meanwhile, the crisis left the American Mission in such disarray that the beleaguered press attaché, John Mecklin, compared the place to the “insides of a mental institution.” The Mission found itself in the strangest of fixes. In the midst of the war’s greatest political crisis, American officials had no sources inside the Buddhist movement, and few among other dissidents. The press had them all, and the reporters were not sharing. It was a classic turnabout. The American ambassador, Frederick Nolting, and the commanding general, Paul Harkins, had refused to confide in the reporters, ostensibly fearing leaks to the Viet Cong. But the unsophisticated Buddhists talked freely, even though leaks could mean death for them. The reporters did not leak and the American Mission was left out in the cold–and angry about it–during its greatest crisis. “Now it was we,” Mecklin said ruefully, “who had become the bad security risk.”

At the White House President Kennedy began getting his news from the New York Times before it arrived in his intelligence reports. John Kennedy would never be an admirer of the rebellious Saigon reporters, most assuredly not of David Halberstam. But at about that time anxious aides remember the president slapping the Times down on his desk and barking: “Why can I get this stuff from Halberstam when I can’t get it from my own people?”

Under the circumstances, the American Embassy’s annual Fourth of July party became less than a gala event. By tradition the national birthday celebration brings together foreign diplomats, officials of the host government, and all factions of an American overseas community. In Saigon during the summer of 1963 this was an electric mix indeed.

At the party the correspondents seemed even more the outsiders–so exuberantly young, so blithely unencumbered by the responsibilities of power. By now, most had beautiful Vietnamese girlfriends: all had the run of an exotic city and a high ride on a story that had become everyone else’s misery. In the sea of tuxedos, dress whites, floor-length gowns, and occasional silken Vietnamese au dais, animosity bubbled with the champagne, particularly among the military wives. Snug in their own caste system, the wives’ social duties rarely brought them face to face with the bylined men causing their careerist husbands so much grief. Now they bristled as the reporters moved through the crowd with brash grins and zesty self-confidence.

Suddenly, Alice Stilwell, the color rising in her face, wheeled on a reporter barely old enough to be a captain under her one-star husband, Brigadier General Richard Stilwell.

“You’re not married, are you?” she abruptly demanded.

Startled, David Halberstam shook his head silently.

“You don’t have children, do you?”

Rarely at a loss for words, Halberstam shook his head again.

“If you did,” the general’s wife continued, bitterly biting off each word, “you’d look at this war quite differently.”

The anti-war mythology that built up later around these first rebellious reporters in Vietnam was just that–myth. There was not a dove among them, surely not Halberstam. At the height of the 1963 crisis, long after the bitter quarrels with American policy-makers had turned him into a publicly self-proclaimed “angry man,” Halberstam waxed with unbounded enthusiasm to a visitor: “This is a great country, much too nice a country to lose.” The early dispute between the press and the American government was about nuts and bolts, not great moral issues or even American strategic policy. So it would be years before Halberstam would concede that Alice Stilwell had a point, although unintended. He would be long gone from Vietnam before he would agree that, older and more mature, perhaps even as a father, he indeed might have looked at the war differently. He might have seen, as he wished he had then, that America had no business in Vietnam at all. At the time the 29-year old New York Times man recovered with a quick cocktail-party riposte:

“Mrs. Stilwell, your man, President Diem, does not have children. If he did, do you think we would have the benefit of an improvement in his view of the war?”

Alice Stilwell stalked away, furious. Her husband, deputy to Harkins and a rising star whom some thought might replace the commander, never forgot the insult, developing a near-obsession about the rude young man from the Times. Most others remembered with greater clarity an event that occurred a few moments later. When the traditional toast was proffered to Diem as the host government’s head of state, Halberstam stood tall, straight, and stern in the middle of the room, his glass clutched to his chest. “I’d never drink to that son of a bitch,” he announced, and he did not announce it quietly.

Three days later the reporters were out in the streets again, covering another Buddhist demonstration. This time Diem’s secret police were ready. In a narrow alleyway they cornered Browne, the great offender at the burning of the bonze, and grabbed his AP colleague, Peter Arnett. Always the story-first reporter, Browne shimmied part way up a telephone pole and began photographing the police as they pummeled and kicked Arnett. It was a dedication to duty that Arnett, a scrapper but also a runt of a man at 5-foot-7 and 145 pounds, did not appreciate for some time to come. Moments later Browne, the real target, was hauled down and his odious Minolta smashed. But the film survived, including one memorable photograph of Halberstam, looming over all at 6-foot-3, stiff-arming the cops as he pulled the pug-nosed and battered Arnett to safety.

The confrontation was the first but far from worst physical battle between the South Vietnamese police and the press. Over the next months, as the regime tottered, the violence escalated into brutal beatings and near-deaths. More than a decade later the police murdered an Agence-France Presse correspondent, the last reporter killed in Vietnam. That occurred in the chaos of Saigon’s fall in 1975. But by the war’s end, more newsmen had been killed in Vietnam than there were American soldiers dead at the beginning of the Buddhist riots in the summer of 1963. These unlikely riots were one of the first crises that turned America’s little war into the beginning of the nightmare to come.

Furious over the Browne-Arnett incident, the correspondents angrily stormed the embassy in search of help. They found none. Mired in an impossible task and even worse luck, Ambassador Nolting, ill-starred as usual, had chosen a most improbable time to take an overdue vacation. Since the first Buddhist burning, the ambassador had been sailing in the far-off Aegean Sea, out of touch with the rest of the world and the turmoil in Saigon. His deputy, William Trueheart, overwhelmed by a month of increasingly nervous pressure front Washington, had pushed Diem enough; he would not add another protest. Trueheart simply stiffed the reporters.

Bitterly, the newsmen cabled President Kennedy directly, accusing his men of refusing them protection. The next day the secret police arrested Browne and Arnett, grilling them for four hours.

Now the four-letter words erupted like mortar rounds, with Mecklin the target. Only weeks earlier, Mecklin had gone over the head of his superiors to make his own personal appeal to Kennedy to calm the “press mess” in Vietnam. The anti-press crusade, he had told JFK, was lurching out of control and could prove deadly to long-term American interests. But now the invective was too much. Angry shouts echoed through his office: The government was “too cowardly” to help and he was a “gutless bastard.” The meeting turned so loud and stormy that a fellow embassy official rushed to his aid, fearing Mecklin might be in physical danger. His advice to Kennedy was correct: Events had run out of the control even of people who knew better. Mecklin stiffed the reporters, too.

In Washington, Kennedy’s frustrations grew with the bad-news headlines, and, privately, the frustrations began to tell. During a visit by Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson, the president made a pro forma request for advice about Vietnam. Pearson’s reply was direct and seemingly simple: “Get out.” Kennedy’s wit and charm disappeared in a flash. “That’s a stupid answer,” the president angrily snapped. “Everybody knows that. The question is: How?”

©1989 William Prochnau

William Prochnau, a freelance writer, is working on a study of media coverage and Vietnam.