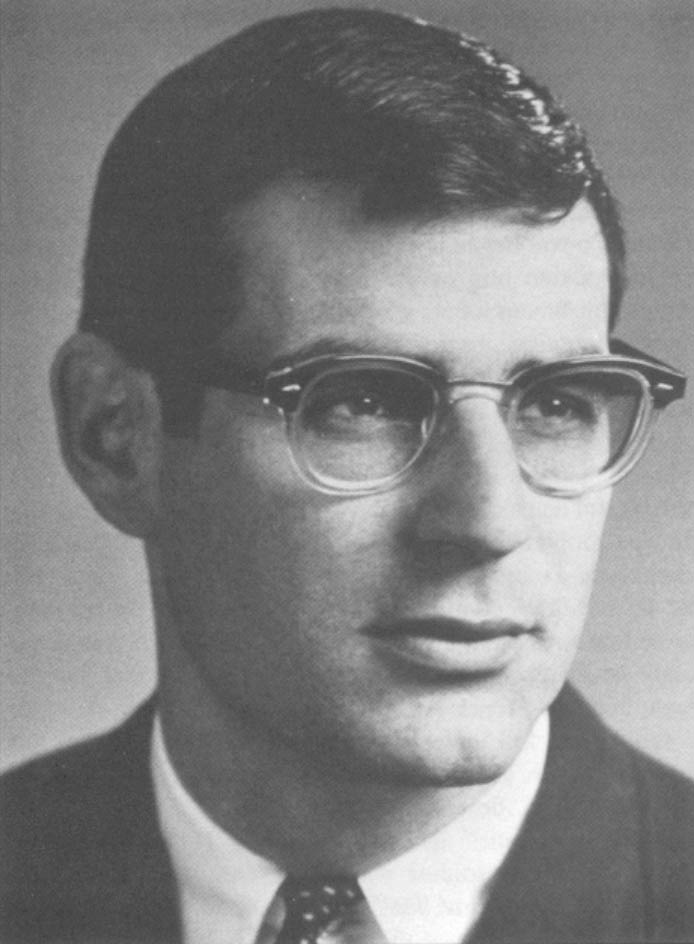

When David Halberstam arrived in Saigon in early September, 1962, his new dateline remained distant and obscure to his readers and even his editors. It would be several months before he would move back onto the front page with the regularity he had achieved in the Congo, the early-Sixties hot spot he had just left. In Vietnam, the United States had quietly increased its military commitment to more than 10,000 men, but the death toll of Americans still stood at just twenty-five, most having died in plane crashes while defoliating Vietnamese forests, dropping psychological-warfare leaflets on peasants, or ferrying troops.

Horst Faas, Halberstam’s buddy from the Congo who had preceded him by three months, greeted him rhapsodically. “You vill love zis place,” he enthused. “It iss VUN-derfull!” The countryside was “like a page out of the Bible” and the people were equally beautiful. It also was safer–”zee boom-boom comes easier.” In the Congo, where nervous rebels once misread his German accent as that of a right-wing Belgian mercenary, Faas had come all too close to a quick and anonymous jungle execution. In Vietnam, the AP photographer said, at least you had a government to pull you out of a Communist, and Faas would ruefully conclude he had come full circle. But for now it was pure adventurous joy.

Halberstam, too, was ecstatic. The South Vietnamese government, America’s ally, might be hard-nosed and unfriendly toward the Western press. Just recently it had expelled Francois Sully, Newsweek’s correspondent, on rather flimsy grounds and Halberstam had heard the warnings about the tensions between the press and the authorities from his New York Times predecessor, the legendary correspondent, Homer Bigart. But he still saw Vietnam as a reporter’s dream.

“This has everything,” he told himself, in awe of his good fortune. “A war, a highly dramatic and emotional story, great food, a beautiful setting, and lovely women.” Where else could he romance a beautiful girl with the best French cuisine and wines in the evening, shower in luxurious hot water at a modern hotel the next morning, take an early cab out to the airport, eat a tense breakfast with helicopter pilots, and then fly off into that special technological high of almost immune combat? And make his reputation at the same time? At 28 years of age, he was young by outsiders’ standards but approaching his prime in a profession that rewards youthful vigor. He represented the most powerful newspaper in the United States and, in the American century, that meant the world. He was ambitious, energetic, smart, self-certain to the edge of cockiness, and he knew from the moment he landed that his timing was perfect. Nothing like this would happen to him again, and he decided to go for it all.

Like Malcolm Browne before him–and most Americans before the journalists–Halberstam became enthralled immediately, caught in an exotic Venus flytrap that was potentially deadly but also irresistible. Also like Browne and the small group of American reporters in Vietnam in 1962, Halberstam found nothing untoward about his country’s commitment to this faroff land. Bred into a first-generation immigrant family’s old-fashioned patriotism, reared during the easy certainties of the Second World War, coming of age during the Cold War, Halberstam saw his country not only as America the Great but America the Good.

Like his country, Halberstam had a strong moralistic bent–too much the self-certain sermonizer, his critics would say. But if Vietnam and its charming people couldn’t defend themselves against the insidious advance of the communists, then his powerful country not only should help but had a moral obligation to do so. America’s client government, the Ngo Dinh Diem regime, made the new man from the New York Times uneasy. But that also was part of the real world; America supported a lot of tin-horn dictators and eventually American influence would moderate them–or replace them. He didn’t question the wisdom of the American presence in Vietnam, not when he arrived nor well after he left, and some of his early dispatches had a decidedly gung-ho ring.

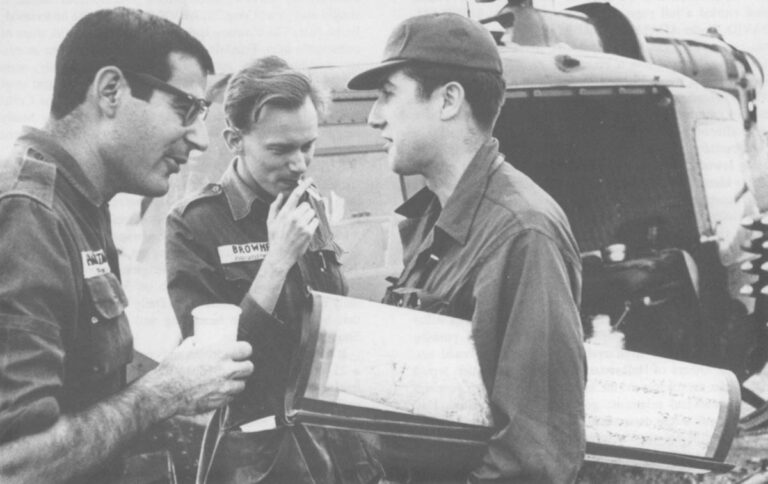

Watching the American military men in action, Halberstam wrote in an early dispatch, “is as impressive as watching Alan Shepard or one of the other astronauts for the first time on TV.” America had its “varsity” playing in “just another extension of the Cold War,” and the varsity was lean, mean, and tough. “There is a swagger to the American walk which is considerably accentuated in American military men…and they don’t seem to doubt that they ought to be here.”

Nor did Halberstam foresee the agony ahead. Two years later he would chronicle these early days in Vietnam in a book called “The Making of a Quagmire” and still later enhance his fame with a devastating analysis of American leadership, and hubris reached, in a best-seller with the ironically accusing and harshly condemning title, “The Best and the Brightest.” Halberstam would become a legend as one of the most questioning and outspoken Vietnam correspondents, symbolizing the beginning of a new era of deep hostility between the press and the government that would last long after the war. Later, after he left and the war began to rip America apart at the seams, some would enshrine him as the first journalistic laureate of the anti-establishment rebels who would storm the streets, fill the air with taunting obscenities, and spell their country’s name with a Germanic “k.” But not once, during his Vietnam years or well afterward, did he question America’s right, even her need, to be there. His criticisms were not of a moral or philosophical nature. His criticisms were of methods and foolishness and delusion, of a failure to set a policy that could win. He was not part of those Sixties excesses, nor of the firebrand journalistic excesses that sometimes accompanied them. Nor did he see them coming. In November 1962 he confidently wrote that America’s experience in Vietnam “will almost certainly never reach the harsh sense of alienation that came to haunt both the French Army and the French people….”

Halberstam fell under the spell and watched the GIs fall, too. His kicker, the final sum-it-all-up paragraph in one early gung-ho article, described a scene in one of Saigon’s new “Honeymoon Lane” honky-tonks along TuDo Street as an enrapt American soldier watched a beautiful Vietnamese singer purr “Lonesome Me” in newly acquired English. The Yank suddenly thumped the bar and exclaimed, just as Halberstam might have done: “My God! We CAN’T let this go over to the Communists.”

So Halberstam was not of the Sixties generation. He was not of any generation, but a man out of the ambivalence of the Fifties whose peers struggled for generational identity of any kind. They had one foot balanced in the righteous self-certainties of Pax Americana, the other sliding into the righteous self-certainties of the bitterness ahead. Such slippery generational footing often provides the best ground for looking in both directions and sometimes the best for truly lasting disillusionment. As time wore on, Halberstam would draw on both vantage points to become not the laureate of an America turned evil but the biographer of his own biting and sermonistic vision of an America failed. He would chronicle the failed dream in Vietnam. He still would be chronicling the loss of the dream with the fall of Detroit to a different group of relentless Asians a generation later. His legacy, partly enhanced by myth, would be the changing of his profession’s mood, the spawning of a new and deeply questioning journalistic style that yielded to few icons, certainly not government icons, except the First Amendment. That style became the controversial standard in Vietnam, peaked at Watergate, and reached a kind of daily guerrilla warfare all its own by the Eighties. Not the smallest part of that legacy was the impact it had on early television, which came into the war years with no legacy of its own.

The real paradox in David Halberstam, who would become such a burr in the side of the American establishment, was that he seemed so predestined, so obligated to become part of that establishment–and that he felt so driven to succeed and fulfill the obligation. He seemed carved out of the dream he later would see as so failed.

The personal story of the Halberstam family read like a multigenerational Ellis Island melodrama. Both sets of his grandparents had been Jewish immigrants, one escaping religious and political persecutions in Poland, the other in Lithuania. Both had large families and, in classic immigrant fashion, sacrificed to thrust one singled-out child closer to their new country’s promise. Blanche Levy was the only member of the Lithuanian family’s first American generation to attend college. She became a teacher. From the Polish family Charles Halberstam emerged as the chosen one and became a doctor, although the luck of his timing would never be as good as that of the two sons he and Blanche begot. Two great wars, the depression and an early death prevented Charles Halberstam from reaping the full promise of the land of milk and honey to which his parents had been drawn. Filled with the pride and patriotism of an immigrant’s son, he interrupted college to become a medic in the First World War, struggled as a young doctor during the economic collapse, and then returned to Europe at age 44 as a combat surgeon in the next war. He died prematurely in 1950, leaving a family he had lifted to the lower middle class economically but taken far beyond in drive and spirit.

The two sons were born in New York City at the height of the Depression–Michael in 1932 and David in 1934. Unlike most Jewish youngsters of their era, they led rootless lives, following their father’s medical and military careers through town after new town–El Paso, Austin, Rochester, Minnesota, and finally to the Connecticut hamlet of Winsted that they came to call home. They grew up brash and independent, forced repeatedly to earn their spurs with each new move. Invariably, they fought only once in each neighborhood. The Halberstam boys were neither tough nor big–David would not sprout to 6-foot-3 till his college days. But they were tenacious. They held ground taken, a quality instilled by their father. People could push you around in the old country, Charles Halberstam told his sons again and again; they could push you around here, too, but in America you could push back. (Michael would die in a tragic and extreme extension of that quality, shot dead after he surprised and chased an armed burglar out of his suburban Washington home in 1980.) Blanche, who filled in the family’s often meager income with part-time teaching jobs, taught them that education would enable them not only to fight back but to join.

The boys were bright, and they brought home the good grades their mother demanded. But, on their own, they also learned a few lessons in mid-century Americana: Good grades. for boys, demanded a certain atonement. So they immersed themselves in the solid American sports, football, basketball, and baseball, at which neither was particularly talented. But they kept at them. No one would ever catch a young Halberstam with a sissified tennis racket in his hand, ruining everything.

At the time of their father’s death, David was 16, his older brother 18, and the family finances marginal. But Blanche Halberstam had no doubts about what lay ahead for her two sons, and neither did they. She sacrificed again and Michael went on to Harvard. David followed two years later. In just two generations the Lithuanian and Polish émigrés had thrust their progeny to the highest hand-hold on the climb to the American establishment.

Harvard cost a then-staggering $1,700 a year, $800 of which Blanche eked out of her husband’s life insurance and the rest earned by the boys during the summers. Michael chose medicine as had his father. David chose more unconventionally–journalism, an intellectually dubious craft that did not yet fit into Harvard’s elitist vision of its duty to prepare the next generation’s leaders.

Sam Adams, an inward and, at the time, aimless nouveau poor classmate who traced his lineage back to the Adamses of the Revolutionary War, remembered David Halberstam as an unapproachable “big man on campus.” Adams would go on to a quite different kind of career filled with remarkable coincidences that might have tied the two together. In the CIA, Adams ran the Congo desk at Langley. where, like a medieval monk, he methodically tabulated random intelligence reports and compiled remarkably accurate counts of the Katanganese rebels Halberstam wrote about. In Vietnam, he took on a similar chore. Within the establishment, Adams became one of the most tenacious silent rebels of the Vietnam era, contrasting with his classmate’s most visible challenge. Twenty-five years after the graduation of the Class of ’55, the Harvard reunion book carried a full page of exploits under HALBERSTAM, DAVID. Under ADAMS, SAMUEL it printed not a word. The two men would meet for the first time five years later–thirty years after Harvard–in a courtroom in New York’s Foley Square during the celebrated libel trial of Gen. William C. Westmoreland vs. CBS. The meeting was somewhat awkward, the two men having traveled such oddly similar life paths in such different psychological garb.

Halberstam’s perspective of his Harvard years was different. Being Jewish, and with neither American lineage nor money, he saw himself as an outsider and felt the Harvard of the Fifties “had accepted us academically but was not yet ready to accept us socially.” So he chose an outsider’s route.

The young man’s timing, as usual, was perfect. The two great wars that had interrupted his father’s life–and the dramatic social changes forged out of the agonies of the Depression–now placed the son at a unique time in history. The wrenchings of the twentieth century had moved the United States into unprecedented affluence and power. Both its dollar and its industrial/military might dominated the world, pushing America finally and irretrievably out of its traditional isolationism. Others of Halberstam’s Harvard generation would make safer moves toward the establishment through economics, international relations. government, or the law. Halberstam was no less determined. But he was drawn to a more electric profession, one “covered with no boredom,” as he put it. And luck was on his side. If, in the early Fifties, training the best and the brightest to hawk the news seemed somewhat beneath Harvard’s lofty purpose, the changed world soon would propel the news of events to a level of importance rivaling the events themselves. Halberstam’s “outsider” decision would place him in a new light often at odds with the establishment. Yet the “newsies” were about to become, at the very least, an establishment substructure so powerful they could challenge the whole. The Harvard ticket soon would provide first-class passage to power even for those with the dirty ink of newsprint on their hands.

Young Halberstam gravitated quickly away from the ivy and into the Plympton Street sanctum of The Crimson building, often spending fifty or sixty hours a week at the college newspaper. He wore a trench coat and drooped a cigarette out of the side of his mouth, not in the fashion of Harvard men but in the fashion of the old hard-drinking, underpaid, socially marginal news reporters of the past.

But these young Crimson aces would not be formed in the old Front Page mold. Anthony Lukas, who would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize, spurned the dreariness of collegiate news and covered the rampages of Joe McCarthy instead, earning the envy and razzing of his collegiate colleagues when the red-baiting senator cheerily began calling him Tony. Halberstam’s best friend, Jack Langguth, eventually would replace him as the Times’ man in Saigon. John Updike wandered around the fringes, writing satire for the Harvard Lampoon and starring for the Poon softball team in its annual embarrassment with the boys from the semi-serious side. One year Updike played eight of the Poon’s nine positions to no avail, the Crimsons winning 23 to 2. Years later Halberstam and another former Crimson man, Stanley Karnow, sent Updike a postcard from Saigon. It simply said: Viet Cong 23, ARVN 2, and Updike understood. In the past, The Crimson had produced more than its share of remarkable men. Franklin Delano Roosevelt had been its editor. Another former editor, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, soon would move into the White House. But Halberstam and most of his young colleagues had no intention of using The Crimson’s pulpit and Harvard’s ticket into traditionally heady realms. Their headiness lay in deadlines; their dreams focused on the New York Times.

Graduating in 1955, Halberstam surprised his Crimson friends, most of whom were using the ticket to lock up jobs with the country’s most prestigious news organizations. Brasher than ever, completely self-confident, and eager to make his mark on the world, he wrote off the newspaper of his collegiate dreams because he didn’t want to get lost in “the Number Thirty-Five slot in the Times Washington bureau.” Instead, he took a $46-a-week reporting job on Mississippi’s smallest daily newspaper, the West Point Daily Times Ledger, certain that he could plunge head-long and influentially into the South’s racial problems.

It told a lot about the driven and cocky youth that he thought a 21-year-old, Harvard-educated, Jewish northerner could freely report events, let alone influence them, in a small, unflinchingly segregated Mississippi town just one year after the Supreme Court’s historic school-integration ruling. His other goal in West Point told even more–to write “for a larger, intangible, invisible journalistic jury, which somehow would know what I was doing and would reward me.”

After seven months, and more intolerable compromises than David Halberstam would endure at any other time in his life, the job ended abruptly when he tried to report the activities of some of the town’s movers and shakers at a local organizing meeting of the supremacist White Citizen’s Council. The Times Ledger’s editor silently read Halberstam’s copy and stared briefly at the young northerner. “David,” he finally said, “you’re free, white, and twenty-one, and can do anything you want.” Halberstam accurately took that to mean in someplace other than Mississippi. The story was killed. He left two days later.

But Halberstam stayed in the South, moving to the respected Nashville Tennessean. For the next four years he covered civil rights and politics, writing occasional articles for the small national political journal, The Reporter. It was those articles that finally reached the “larger, intangible, invisible journalistic jury.” He was spotted and recruited by James (Scotty) Reston, the New York Times’ Washington bureau chief.

Halberstam joined the Times in 1961 and ended up in the pickle he had feared: The Number Thirty-Five slot in a Washington bureau of thirty-five reporters. He hated it, and he did poorly. Very poorly. Even as the capital began to throb with the promise of historic change, Reston watched his bright, 26-yearold recruit flounder about, lost. Finally, Reston pulled him aside and softened the news with a classic Times side-slip. “Dave, maybe you need a hotter climate and darker people,” Reston said, making it sound as if he were sending Rudyard Kipling off to colonial glories. Halberstam leapt at the offer and found himself en route to equatorial Africa.

Halberstam landed in the Congo with his trench coat, a stylish collection of Abercrombie & Fitch bush clothes, and a variety of anti-dysentery potions whose vastness was exceeded only by his enthusiasm. Henry Tanner, the exhausted resident correspondent for the Times, had been covering the newly independent country’s chaotic tribal civil war for most of a year. He took one weary look at his eager young replacement and wished the new man luck with his useless array of medicines. Then he dryly observed, one Times man to another, that the trench coat surely would keep Halberstam warm, and bush clothes by Abercrombie & Fitch were an ingeniously daring idea in a country where European mercenaries were favored targets. Halberstam changed outfits, and thrived.

Over the next twelve months the front page opened up, the first awards rolled in, and he received the war correspondent’s obligatory blooding–a minor flesh wound from bomb shrapnel. Halberstam was on his way, although it was far from clear that he was on his way to a new kind of war correspondence that would place him in direct conflict with his own government and often his own colleagues.

In the Congo, Halberstam played by all the set rules. He checked in regularly with the CIA men, and, in the accepted fashion of the day, thought nothing of doing a little routine information trading. He became close friends of the American ambassador, Edmund Gullion, and found no reason to distrust him, just as Gullion found no reason not to confide in Halberstam. The stories from the Congo, which were considered bigger news at the Times than Homer Bigart’s pieces from the little war in Vietnam, did not always follow the American line. But they even more rarely diverted from it. Halberstam was one of the boys.

©1989 William Prochnau

William Prochnau, a freelance writer, is working on a study of media coverage and Vietnam.