A few months ago, the Internal Revenue Service handed out a two page press release describing a new computer tracking system it has recently cranked up. The IRS said the system had two distinct goals; improve the detection of those individuals who don’t file any income tax returns at all and automatically calculate what they owe the government.

Perhaps because the announced target of the new system has always been considered a loathsome class, genus tax cheat, the IRS plan received little notice.

But the January startup of this complex automated detection system by the nation’s largest and most powerful civilian agency represents the culmination of a major series of technological advances in the administration of the 74 year old federal income tax. At the same time, the new system may provide the clearest warning yet of an impending shift in the basic relationship between the American people and their government, an increasing pacification of the citizen taxpayer.

The initial goals of the new Internal Revenue Service system seem relatively modest. At very little cost to the government, the computers of the IRS have been instructed to make a list of everyone in the United States who received salary from an employer or interest from a bank or alimony from a former husband or dividends from a corporation or royalties from a publisher or rent from a tenant or a refund from a state tax agency and many other kinds of payments but then failed to file an income tax return.

The second step is more challenging for the machines. Take the list, add up all the income reportedly received by each miscreant, prepare an income tax return complete with the taxes they allegedly owe and then mail out all necessary warning notices and follow up correspondence.

In the first year, the IRS hopes to target 400,000 such “nonfilers” and actually move against 300,000 of them. The agency estimates that the first year assessments–the government’s initial calculation of the total it believes these tax cheats owe the tax man–will tally $2 billion. As the computer engineers like to say, this obviously is a “non-trivial” process.

“If the program works the way we want, the next few years will see a significant drop in the number of people who previously had just walked away from their obligations and paid no taxes,” said William Wauben, the assistant IRS commissioner for collection. “We think the new system will push people toward voluntarily complying with the tax laws.”

The system is a technical marvel.

But the system behind the system is just plain astounding. Beginning about ten years ago, the tax committees of the House and Senate and the top brass in the national IRS headquarters began to sense that developments in computer technology had moved along to a point where the government could seriously consider launching a tax enforcement technique that it had dreamed about for a long long time.

The legal requirement that every institution report to the government how much its paid its employees and withhold a portion of the pay check for taxes has been in place since 1943. For the last four decades, this law has guaranteed that most of the country’s working stiffs, those who had no source of income other than what they earned from their employer, met their federal tax obligations.

For those who received part or all of their income in the form of dividends, interest or royalties, however, it was a different story. It was true that in 1939 the government had been granted authority to force the banks and corporations to report the interest and dividend payments they were making to their customers and stockholders. But except for two very brief periods, Congress has never required the banks and corporation to withhold the federal tax that was due on these kinds of payments.

Without the bite of withholding, the bark of the so called 1099 reporting forms at first had a minimal impact. This was because the 1099’s initially were submitted to the government on paper. Even the massive IRS did not have sufficient funds to hire the thousands of clerks it would have needed to match the hundreds of millions of interest and dividend reports with the correct tax return.

But fairly recent developments in computer technologies have changed that. Now, all the information contained on every one of the 100 million individual tax returns filed each year is swiftly transferred to an electronic master file and virtually all of the 1099 reports are submitted to the IRS on tape or computer disk.

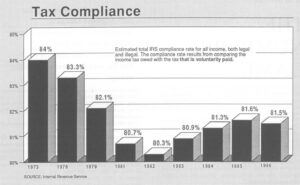

The transition from paper to computer has had an enormous impact on the IRS’s enforcement efforts. Last year for example, employers, banks and other payers sent the IRS close to one billion income information returns. In 1986, IRS computers were able to compare the information contained in 95 percent of these 818.6 million third party reporting documents with that on the 100 million tax returns filed by individual taxpayers.

This ability to read and compare massive amounts of data at very little costs and with extraordinary speed, allowed the IRS in 1985 to identify 4 million citizens who filed returns but failed to include one or more of these third party payments as part of their total income.

In addition, the computers identified about 3 million individuals in this country who last year were reported as receiving some kind of payment but failed to file any kind of tax return at all.

The computer equipment, software, authorizing law and regulations needed for this massive and apparently successful computer matching program have been in place and operating for several years.

The procedure that is new, the one that the IRS announced in January, goes a big step further: after the computers have scanned all the computer notices filed by employers and 27 other categories of payers, and targeted the individuals receiving income but not filing a tax return, the machines will automatically churn out a “substitute tax return,” including an assessment of the taxes that is owed the government. Before the IRS actually sends this substitute return to the suspect, the computers spit out preliminary warning notices. After the machine generated return has been mailed, come several follow up warnings. If there still is no satisfactory response, the heavy enforcement guns of IRS’s collection division, such as the seizure of the target’s home and savings account, will be triggered.

The IRS’s January Fact Sheet on the “automated assessment procedures” said the new system was aimed at the tiny fraction of Americans who totally flaunt the law and fail to file any income tax return. But for more than 30 years, the IRS has been fascinated with the possibility of establishing a quite similar procedure that would calculate the tax obligations of a majority of all taxpayers, not just the cheaters.

A national system where the government would assume responsibility for calculating the taxes owed by two thirds of the American people may not sound like a major change, but it flies in the face of the central premise of the American tax system and the rhetoric of generations of IRS officials.

The American people, the officials have contended, are different from the citizens of most other countries. The American people, imbued with a unique love for their nation, pay their taxes on a voluntary basis.

Despite the enthusiastic lip service paid to the spirit of “voluntary compliance,” the IRS has long yearned for a more intrusive system. As far back as July of 1953, the planning staff of what was then known as the Bureau of Internal Revenue Service, completed work on a secret study “to eliminate the need for filing tax returns by wage earners when tax is withheld by employers.” The first benefit of the 1953 proposal, the planning document said, would be to reduce “the burden of the wage earner.” But the plan gave equal weight to another goal: “safeguard the revenue” by “reaching more people for annual tax accounting.”

The IRS’s 1953 plan to collect sufficient information about the citizenry to enable it to calculate the tax obligations of a large part of the population did not fly, probably because of the impossible bureaucratic burden of manually matching hundreds of millions of pieces of paper containing the income information.

But three decades later, in November of 1984, the proposal was resurrected by Donald Regan, then Secretary of Treasury, in a report to President Reagan. The report bore the title: “Tax Reform for Fairness, Simplicity and Economic Growth.” By this time, Mr. Regan and the IRS had come up with a catchy soft sell advertising phrase for what is in fact a revolutionary plan. “The return-free system” was now possible, the report said, because the IRS’s improved information processing equipment would allow it to calculate the tax liabilities for many Americans. As a result, Mr. Regan called for the initiation of the system “under which may individual taxpayers will be relieved of the obligation of filing an income tax return.” The public reports about the 1984 proposal, unlike the 1953 version, contained no language suggesting that the IRS’s support for the system was partially grounded on its ability to better “safeguard the revenue.”

In late 1984 and 1985, Roscoe L. Egger Jr., the IRS Commissioner at that time, continued to beat the drum for the return free system, what he called a “very exciting proposal.” By 1990, he predicted, 2 out of 3 taxpayers “would never have to wrestle with a tax return again.” At about the same time that Mr. Egger was publicly speaking about the plan, the IRS was preparing its Strategic Plan, a long term policy paper about anticipated direction of the agency. It too called for the implementation of a system where the government, rather than the individual, would calculate the taxes owed by well over half of the population.

Congress was less enthusiastic. In the final version of the 1986 Tax Reform Act, a brief section was added authorizing the IRS to initiate a small experimental project to test the “return free” concept. Concept testing is now going forward in the IRS’s Office of Tax System Re-Design.

Thus, while implementation of the return free system for two thirds of the American taxpayers has been slowed, the IRS has aggressively moved ahead in the development of the somewhat smaller but quite similar automated assessment operation announced by Mr. Wauben in January.

There are three distinct and significant questions that should be raised about the IRS’s new drive to reduce the deficit by nailing all those tax cheats who are putting the burden on the rest of us.

First there is the apparently simple question of accuracy. In systems as large and complicated as those operated by the IRS, an apparently small percentage of inaccurate or ambiguous entries can very easily result in wrongful government actions against hundreds, and even hundreds of thousands, of innocent people. Depending upon the number of injured, and the government action actually triggered by the false information, such projects can sometimes lead to serious violations of the Constitutionally guaranteed rights such as the 5th amendment’s fundamental promise of due process.

A few years ago, for example, a Texas woman was sent an IRS notice asserting that she had failed to report $4,000 of her income and demanding $800 in back taxes, penalties and interest. It turned out, however, that the IRS’s assertion was dead wrong.

In fact a preliminary investigation turned up evidence that the Texas woman was not the only victim. It seemed a local bank had purchased some software, or computer instructions, that was supposed to enable the bank’s computer to automatically prepare a list of the names and addresses of the bank’s customers to whom it had paid interest. But sad to say, the software was faulty, and the bank had inadvertently informed the IRS that 200 of its customers had received interest when they had not. These incorrect reports, of course, triggered the IRS’s computers to kick out 200 incorrect dunning notices.

It is worth noting that the investigation that uncovered the faulty software was triggered by a newspaper story about the rash of incorrect notices, and not an internal audit.

But the trail did not end there. Further investigation found that the faulty software had been sold to at least 50 other companies which in turn had sent the IRS incorrect income reports concerning approximately one million individuals all over the United States. To this day, the IRS insists it does not know how many incorrect dunning notices it actually dispatched to terrified taxpayers.

A million incorrect IRS dunning notices may only be one million momentary heart attacks, hardly grounds for constitutional challenge in the courts, even if the courts could figure out who was responsible for the incredible mess. But when the automated system starts triggering the seizures of bank accounts or homes, even the most obtuse federal judge may begin to worry. The IRS, of course, insists that more than adequate protection is provided by its elaborate notice system. But in a nation as large and mobile as the United States, it’s not possible to assume the notices will always get through.

The experience of the Federal Bureau of Investigation is not reassuring. Despite the earnest efforts of the FBI, recent audits have determined that a significant percentage of the tens of thousands of entries that it transmits around the country each day are inaccurate, incomplete or ambiguous. The result: innocent people sometimes are arrested, guilty people sometimes go free and patrol officers sometimes are unnecessarily endangered. Individual victims living in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Michigan, Louisiana and California have brought suits charging that their constitutional rights were violated when the incorrect information in the computers led to their false arrest.

No similar audits of the accuracy and completeness of IRS data ever have been made public. But anecdotal evidence from IRS personnel working in different parts of the United States suggest that similar problems plague some of the computerized data bases of the tax agency.

The second key question goes beyond the set of problems presented by inaccurate data. Assume, for argument’s sake, that we live in a world where every bit of information in every one of the IRS’s computers is accurate and that every IRS notice is correct. Do the American people want a world where much of the personal information collected by the IRS is routinely shared with state and local tax agencies? Do the American people want a world where the IRS, to improve its enforcement efforts, has initiated a long range plan to gain direct access to a wide range of information collected by the states during the registration of automobiles and voters and the licensing of drivers, doctors and other groups? The American people have long resisted the development of a single national data base. But the Office of Technology Assessment, a research arm of Congress, warned last year that a de facto system already was in place.

Because this growing electronic net is being tossed over the country in the name of worthy causes such as fighting crime and catching tax cheats, the nation’s current leaders have not responded to the challenge of men like Joseph Weizenbaum of MIT or the late Sam Ervin, the constitutional scholar and Democratic senator from North Carolina. Senator Ervin believed that computer technology threatened to erode liberty and the creative spontaneous spirit of the American people. Unless new legislative controls can be devised, unless federal officials can be persuaded to exercise more self control, he once warned, “this country will not reap the blessings of man’s creative spirit which is reflected in computer technology itself.”

Return Free System

Benjamin R. Barber, a professor of political science at Rutgers University in New Jersey raises a third question, based on the assumption that IRS’s current automated assessment project and existing technology will lead to “return free” procedures for most citizens. “If the IRS moves ahead with the return free system–which seems almost inevitable–we will see a profound change in one of the basic roles of the citizen,” he said in a recent interview.

“The citizen becomes even more passive than he is today, the government more active. Instead of the citizen telling the government what taxes are due, the government, like Bloomingdale’s, will just submit its bill to the citizen,” he said.

Professor Barber noted that filling out the tax form served an important civic function. “It makes you wonder where the money is going. Who is getting the various possible deductions? You need active engaged citizens if representative democracy is to survive and flourish. The government’s desire to take over a key responsibility of every citizen is just one more step in the continued pacification of the American people.”

Remarkably, almost 150 years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville expressed the same concerns. Tocqueville, of course, celebrated the great American experiment. But he worried that the egalitarian spirit of its people could lead to the growth of a despotic centralized government. Such a government, Tocqueville wrote in “Democracy in America,” would cover “the surface of society with a network of small complicated rules, minute and uniform, through which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate, to rise above the crowd.”

The subtle despotism of democracy, he said, “does not destroy, but it prevents existence, it does not tyrannize but it compresses, enervates, extinguishes, and stupefies a people, till each nation is reduced to nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which government is the shepherd.”

©1987 David Burnham

David Burnham, a freelance reporter, is investigating the Internal Revenue Service.