SPARTANBURG, S.C.–In 1982, Jan Johnson decided he had a Christian duty to become involved in politics “to help save America.” He spoke to members of his church, Evangel Temple. A handful, including pastor Charles Gaulden, joined him to become delegates to the state Republican Party convention.

This year Johnson and Gaulden helped lead a conservative Christian campaign that swamped precinct elections across South Carolina. The “Christians,” as the movement became known, jammed delegate-selection meetings that typically draw just a handful of party activists. More than 150 Evangel Temple members were elected to a convention where they wrestled with the GOP “regulars” for control of the state wide party machine. The battle, fought to a virtual draw, stunned the regulars and made the Christians the party’s power brokers. They now have the strength to control executive positions and nominations to the 1988 national presidential convention.

This year Johnson and Gaulden helped lead a conservative Christian campaign that swamped precinct elections across South Carolina. The “Christians,” as the movement became known, jammed delegate-selection meetings that typically draw just a handful of party activists. More than 150 Evangel Temple members were elected to a convention where they wrestled with the GOP “regulars” for control of the state wide party machine. The battle, fought to a virtual draw, stunned the regulars and made the Christians the party’s power brokers. They now have the strength to control executive positions and nominations to the 1988 national presidential convention.

South Carolina is the second state where conservative Christians have rushed local caucuses. Earlier this year, the Christian Right proved its status in the Michigan GOP, forming an alliance with Rep. Jack Kemp’s forces to defeat Vice President George Bush’s camp in a struggle for control of the state party. Organized, well-financed and highly motivated, the Christian Right is emerging as an independent political force in America.

Spartanburg’s Jan Johnson is typical of thousands of new conservative Christian activists. Seasoned and aggressive, they are determined to move American politics and morality at least one step to the right. “There’s no question that we’re surprising them,” says Johnson, a broad-shouldered man who moves comfortably in the “good-old-boy” atmosphere of Southern politics. “But they better get used to us, cause we’re here to stay.”

Like many of the new Christian activists Johnson has long held conservative political views. And, like many, he grew up believing that politics is evil and unchristian. Conservative Christians had withdrawn from active political involvement after the Scopes trial of the 1920’s, when believers were widely criticized as backward and ignorant. Bruised by that experience, conservative pastors taught that the whole political realm would pollute a Christian life.

In the early 1980’s, Johnson and others were influenced by the anti-abortion movement and by activist television preachers who began to encourage believers to get involved in politics. On a local level pastors like Gaulden began to get involved themselves. Since then Johnson has undergone a political and theological transformation. He once thought politics was beneath a born-again Christian. Now he revels in the political ‘hard ball’ played by leaders of what is commonly called the Christian Right. And he looks with satisfaction on his recent, well-planned victory.

“We see the system, society, getting more and more secular and less and less Christian,” he says. “Now we know we can change that.”

America’s 60 million conservative Christians–evangelical, fundamentalist and charismatic Protestants are divided by theological nuances but united by conservative political views. Repeated surveys show them joined behind an agenda that includes; a strong national defense, a ban on abortion, a return to school prayer, anti-communism abroad and free-market economic policies at home.

Johnson and Gaulden are part of a new, second wave of Christian Right activists who are charismatics. About 10 million strong, Charismatics believe in healing and speaking in ‘tongues.’ They emphasize a highly emotional worship style. The Rev. Pat Robertson, who is a charismatic, has brought his followers into the political arena where he hopes to join them with fundamentalists and evangelicals, including the nation’s 14.6 million Southern Baptists.

All of the conservative Christians are motivated by a religious outlook that concludes that America is a uniquely blessed nation now falling away from God. The movement’s leaders cite legalized abortion, the ban on school prayer, drug use and other social ills as evidence of a fall from grace. They are driven to restore both political conservatism and conservative, literal interpretations of the Bible.

“This Country was founded on Christian principles, but our leaders have gotten away from that,” says Orin Briggs, a South Carolina lawyer with working class roots common to conservative Christians. Briggs worked his way from a textile mill’s company housing through a fundamentalist college and then law school. After law school he went to Washington to work for conservative Sen. Strom Thurmond, a Republican. He returned to South Carolina in the late 1970’s to found a local political group called Christian Action. He has spoken to hundreds of church groups in the past 10 years, each time delivering a polished sermon on the Biblical imperative for Christian political action. He says that God has declared church, family and government to be special areas of responsibility for Christians, “and we have long neglected one of those.”

Briggs’ efforts are fueled by an urgent, religious sense of doom. “God has blessed America abundantly, but we’ve turned away from Him and if we cross a certain point, He’s going to abandon us,” he says. Briggs, and many others in the Christian Right believes AIDS, the fatal, sexually transmitted Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, is evidence of God’s displeasure. AIDS struck first, and hardest, in the homosexual community, and conservative Christians are stridently anti-homosexual. “The Christian movement is a reaction, to things like AIDS and to the fear that God might abandon us,” Briggs adds.

Other Christians view America’s economic problems, and even the Iranian hostage crisis of Jimmy Carter’s presidency, as warnings from God. Carter brought the term “born-again”–which refers to the believer’s spiritual rebirth when he commits his life to Jesus Christ–to the national consciousness in 1976. While they supported him in large numbers, born-again Christians, who are overwhelmingly conservative in their politics, were disappointed by Carter’s presidency.

Ironically, the Christian Right emerged as a stronger political force in the 1980 presidential campaign, turning out to defeat the first born-again, Southern Baptist president in history. Unlike Carter, who held more liberal views, Ronald Reagan captured the movement’s highly orthodox view of religion and America. He also articulated their disappointment with Carter. Following the urgings and organizing of television preachers such as Rev. Jerry Falwell, they voted for Reagan en masse. They did the same in 1984, reelecting a president who shared their Christian agenda.

With Reagan leaving politics after two terms in the White House. and their agenda largely unrealized, conservative Christians are now moving from a supporting role to direct action. They are building their own political organizations, legal foundations and an intricate grassroots network. The movement has highly-developed fund-raising operations and even its own presidential candidate, Robertson. The surge in Christian political power, first felt in presidential politics, is now evident on the local level. The maturing Christian movement can seize control of a local school board or blitz a state GOP convention.

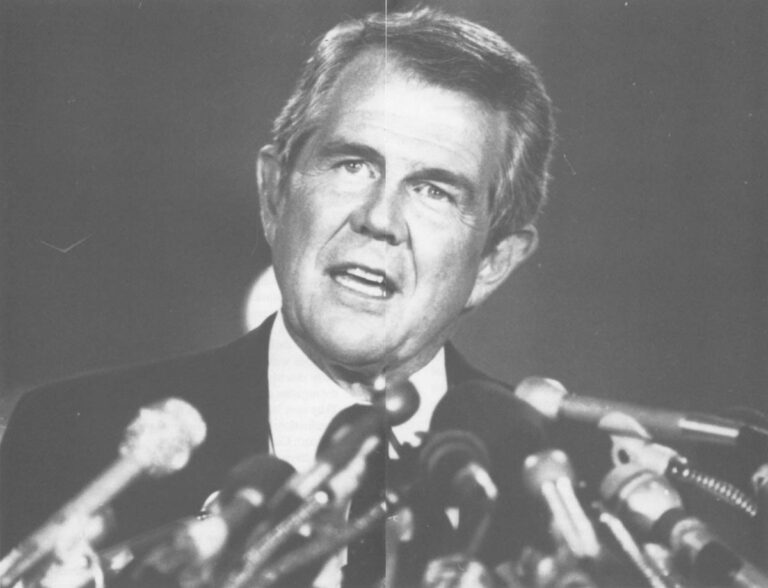

The Christians’ South Carolina blitz featured an alliance of independent Christian organizations and Robertson’s well-developed presidential campaign. By mid-1987, Robertson’s unofficial campaign boasted the largest paid staff in the race–75–and was active in 17 states. Robertson’s fundraising efforts, totaling more than $7 million by midyear, far exceeded the other GOP candidates. The money was raised in much the same way Robertson raises $200 million per year on his 700 Club television show. A 1986 television broadcast, viewed by followers who attended simultaneous meetings at churches and halls across the country, helped Robertson develop a list of 200,000 contributors and potential activists. That list, combined with lists of the hundreds of thousands of contributors to his TV ministry, gives Robertson an extraordinary base of support he can access with his extensive computer operations.

Robertson organizers targeted South Carolina because it is emerging as a “New Hampshire of the South.” State party officials will hold South Carolina’s GOP primary three days before Super Tuesday, when most of the rest of the South chooses presidential candidates. South Carolina officials hope that by moving up their election, they can make the results more important. They hope to influence the media and voters eager to know which candidate has momentum.

Relying on an already-established network of contacts developed by his ministry, Robertson formed an alliance with local Christians, including Jan Johnson and Orin Briggs, at informal meetings early this year. Although this year’s precinct meetings did not select delegates specifically pledged to presidential candidates, the caucuses were considered a test of candidate strength. Vice President George Bush. whose campaign manager is South Carolina’s Lee Atwater, took a strong interest in the caucuses, but Robertson forces worked in churches and Christian organizations to develop a full-fledged campaign.

The Christian activists worked, unnoticed, until one week before the March precinct meeting when Robertson arrived for an inspirational pep rally. The rally was followed by an instructional session at a Columbia high school where campaign leaders performed a skit that showed first-time activists how to take over a precinct. A week later the conservative Christians followed the script, winning a majority of delegates. Party regulars prevented a complete takeover when they invoked some obscure rules to deny the selection of about 90 Robertson supporters, cutting their share of the delegates to the state convention to just under 50 percent.

“They have set themselves up in a way that if they vote as a block, they can dictate much of what the party will do,” says Scott Elliott, a party regular who is GOP chairman for Richland County, where the state capital of Columbia is located. ‘What bothers me is that they seem to have a restricted agenda. They might not be willing to work for the Republican Party. They support Pat Robertson and the Christian agenda, but will they help elect state legislators and town councilmen?”

Elliott says that the Christian activists surprised party regulars. “We first tried to work with them and eventually had to simply do what we could to beat them,” he adds. Elliott says the Christian activists’ zeal and religious fervor might harm GOP campaigns. As evidence he points to campaign literature that refers to GOP leaders as a “politburo” and describes Vice President George Bush as untrustworthy. One Christian group opposed to abortion distributed literature that asked, “George Bush, Convert or Con man? Pro-Life or pro-death?”

The struggle over the South Carolina GOP “demonstrated that there is a national base, already existing in the churches, that can be tapped,” says Ray Moore, Robertson’s South Carolina campaign director. Moore is one of a new breed of conservative Christian political operatives. A theological school graduate and former church pastor, Moore has been involved in ten congressional races since 1980. He likens conservative Christians to the labor movement of the 1930’s through the 1960’s, when it could deliver blocks of votes, money and victory to local and national candidates.

“There’s Christian radio and TV. Christian publications. We can be active in a state for months and never bump into other campaigns because we’re in the Christian community. Then they’re surprised when we turn up at precinct meetings.”

The South Carolina offensive followed a similar sweep in Michigan in February when conservative Christians joined with supporters of candidate Jack Kemp to seize control of the GOP central committee. After the Michigan battle, in which Robertson forces claimed to win 53 percent of the state’s convention delegates, Robertson suggested he might consider Kemp as a running mate in 1988.

While they master precinct politics, Christian conservatives also are growing more sophisticated in the way they press their agenda outside the electoral process. They have become effective lobbyists in state legislatures and Congress and also use the courts to pursue conservative change. Activist lawyers, supported by legal foundations such as the Rutherford Institute and the National Legal Foundation, have won two important federal decisions on cases involving the public schools. In Tennessee, a federal judge found that conservative Christian students cannot be required to read literature that they believe damages their faith. In Alabama, a federal judge removed 44 textbooks from public schools because, he said. they promote an anti-Christian religious viewpoint. Both cases were aggressively pursued by young conservative Christian lawyers who liken their cause to the civil rights movement of the 1960’s.

“This is really a liberal case, a civil rights case we’re arguing,” says Thomas Parker, a Christian lawyer in the Alabama case. “In the 1960’s, civil rights lawyers argued that blacks were being discriminated by being excluded from the public schools. We’re arguing that Christians are being discriminated because their viewpoint is being excluded from the public schools.”

While the constitution prohibits schools from teaching religious doctrine, Parker has argued that school materials that seem to erode faith in concepts such as God’s literal creation of man and the universe, are in fact religious. A federal judge in New Orleans shocked educators nationwide last March when he agreed.

Parker is typical of the new, well-trained Christian advocates. Educated at Dartmouth, he says, “I came to accept the secular. relativistic way of thinking.” When he returned to practice law in Alabama, Parker also returned to his Southern Baptist roots, and a more conservative political religious viewpoint. “I realized that Christianity gave me a firm way of deciding what was right and what was wrong,” he adds. Now he uses his training, and his faith, to press for the conservative Christian political agenda.

The rise of more sophisticated, more educated and conservative Christian activists reflects the great upward social mobility of the fundamentalist and evangelical Christians who are the core of the Christian Right. Long a fixture of the less developed rural South and Midwest, conservative Christianity has grown since the 1960s while other denominations have struggled to remained stable. At the same time many of the Sunbelt states which also make up the “Bible belt” have enjoyed dramatic economic growth. In his study of conservative Christians, political scientist John Hendricks found they have, since 1960, risen from well below mainline Protestants to nearly even in measures of wealth and education. Conservative Christians are no longer poor, rural and politically weak.

“This group has gone from feeling defensive and possibly inferior to feeling aggressive, eager to take over an evil world and make it right for God,” says Robert Wingard, a professor of religion at Southern University in Birmingham, Alabama. “Because of their upward mobility they now have the time, the money and the interest to follow their agenda.”

In South Carolina, Henry Jordan, a surgeon, is part of the rising professional class among conservative Christians. An Air Force veteran of Vietnam, he is committed to Christian Right politics. Unlike lawyer Orin Briggs, who grew up in the blue-collar South, Jordan comes from a long line of moneyed Southerners. His turn toward a more conservative local church is common among the younger professionals who are seeking more religious certainty in a complex age. He was motivated, in part, by a spiritual hungering and moved by the messages he heard while watching television evangelists during late night breaks from hospital duty during his medical training.

“I was sort of like America is,” Jordan says. “I was arrogant, comfortable. I was a doctor with some money and an attractive wife. But something was missing. Now I believe in the Bible. I believe in the inerrancy of scripture,” says Jordan, a tall, youthful man of 41. Many born-again Christians believe the Bible is inerrant, which means it is without factual error. Jordan’s faith was followed by a call to politics when local Christian activists encouraged him to run for Congress. Now Jordan’s medical office is decorated both with study Bibles and a lamp fashioned to look like a Republican elephant’s head. In the waiting room, newspaper clippings and photos of Jordan with prominent Republicans fills a cork bulletin board.

Jordan lost his 1986 bid for Congress, but plans to run again in 1988. In the meantime he has become part of the Robertson alliance, working in the small city of Anderson, trading political favors with the Robertson machine. In ’86 Robertson ran television commercials on his Christian Broadcasting Network in which he declared his support for Jordan’s congressional bid. In 1987, Jordan threw his weight behind the Robertson presidential campaign. He says that Robertson has promised to share his list of South Carolina contributors when the 1988 congressional races begin. “It’s definitely part of the deal,” says Jordan.

Deal-making and coalition-building are signs of a maturing political movement. Political scientist James Guth, at South Carolina’s Furman University, says the Christian Right has moved beyond the introductory stage of politics. “There was a time when the less sophisticated religious believers were confronting the world of politics for the first time,” he says. “It was easy for them to rally behind Reagan. Now they are trying to move into party politics, to become influential in a more institutional way.”

The rough-and-tumble of politics will challenge those who hope to remain orthodox conservative Christians, adds Guth. “If they want to succeed on a broad scale they are going to have to meet other people and deal with them. In the process they might be changed themselves, mellowed, and lose some of their conservative edge.” So far, Guth’s studies have shown that the Christian movement has trouble attracting support outside the ranks of believers. Guth’s analysis shows that Robertson’s $7 million war chest, for example, has been built almost entirely on money sent by born-again Christians.

“In the short term, that might mean we won’t accomplish everything we want,” says Ray Moore, the preacher-turned-politician who heads Robertson’s Southern campaign. “But when I started I didn’t think Robertson had a chance. Now I do. And anyway, we’re thinking of long range, 20 year goals. We’re just becoming an influence in society. There are millions of people out there for whom the Bible is the main thing. We’re going to get them involved for the first time and it has to make a difference.”

©1987 Michael D’Antonio

Michael D’Antonio, a reporter on leave from Newsday, is reporting on the Christian America.