The neighborhood surrounding Stony Island Avenue and 75th Street on Chicago’s South Side is middle-class to poor and mixes industry and stores on its main thoroughfares with homes and apartments on the side streets. On 75th Street just east of Stony Island, a bright blue awning stands out from a nondescript brick storefront. Neat white lettering advertises, “The Women’s Center.”

Inside, amid soothing surroundings, a woman can talk about stress with a nurse, be examined by a gynecologist or get a mammogram to check for breast cancer.

Inside, amid soothing surroundings, a woman can talk about stress with a nurse, be examined by a gynecologist or get a mammogram to check for breast cancer.

The center is owned by Jackson Park Hospital and Medical Center, whose buildings fill the rest of the block. The hospital decided recently that opening The Women’s Center was a good way to generate business since women traditionally visit doctors more than men and also make health care decisions for the whole family. In fact, a national survey of hospitals recently dubbed women’s centers “the” hot product line of 1986.

“The center gives the idea, ‘This cares for you and your problems,’ ” explains Dr. Peter Friedell, president and medical director of Jackson Park.

“It was my attempt to be upscale. A women’s center is very trendy,” Friedell acknowledges with a laugh.

A 20-minute ride north of The Women’s Center, on the city’s Near West Side, lies Cook County Hospital. Its gray, neoclassical bulk looms over the sidewalk. To its emergency room three days before Christmas came John Thompson, age 39, unemployed. Hit by a car on the South Side earlier in the day, Thompson (not his real name) was initially taken by a city ambulance to Jackson Park Hospital. There, doctors diagnosed and stabilized him. Then, they called a private ambulance and transferred Thompson to the trauma unit of Cook County, the city’s public hospital.

The reason for the transfer is checked in a neat box on a County hospital form: Thompson has no insurance.

In the trauma center’s front room this gray and chilly evening, a neurosurgeon pricks Thompson’s feet and legs with a needle to test possible nerve damage from compression fractures of the spine. The compression fractures are in addition to injuries which include a lacerated scalp and broken legs.

“Does this hurt?” asks the neurosurgeon.

“Yes!”

“Here?”

“Yes.”

“Is this sharp?”

“Yes.”

For the trauma unit physicians, who specialize in auto accidents, gunshot wounds and stabbings, this case is routine. Half the unit’s patients are brought directly by ambulance or come themselves to the hospital; half are transfers In 80 percent of the transfers, the reason given is “no insurance,” according to Dr. John Barrett, the trauma unit’s director.

For Jackson Park Hospital, this case is routine, too. “If you have no means of compensation, and you’re stable and Cook County will accept you, you’ll be transferred, 100 percent of the time,” Friedell says. “Self-pay” and free care patients cost the hospital an estimated $300 a day, Friedell explains. He says the “transfer when possible” policy was instituted in 1985 after Jackson Park experienced several years of red ink. It was the hospital’s first deficits since its founding in 1913.

Even with the transfer policy, about 8 percent of Jackson Park Hospital’s revenues go to uncompensated care, compared to a national average of slightly under 5 percent. Says Friedell, “Jackson Park [Hospital] decided to stay in this community. It had an opportunity to move out and didn’t…[But] this is a survival issue.”

It is also, Friedell acknowledges, an illustration of the new “upstairs-downstairs” of medicine. In a manner perhaps unseen since the advent of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965, a growing number of medical decisions are being made using the kind of bottom-line scrutiny that motivates any business. To those “upstairs,” with money to pay the bills, health care providers are reaching out with more and better services. Patients who are “downstairs,” on the other hand, with inadequate or no insurance, are discovering that care is increasingly difficult to find.

Upstairs and Downstairs

Paul Keckley, a Nashville-based marketing consultant to physician groups, hospitals and health maintenance organizations (HMOs), summarizes the change this way. “We’ve always had wards for those who didn’t pay and private rooms for those who did,” he says. “But we have formalized the process, and the number of steps between upstairs and downstairs are greater now.”

For years, physicians and hospitals have financed care for those who couldn’t pay by upping the bills of those who could. This implicit, but universally-accepted, “charity tax” was made possible by a generous reimbursement system that essentially paid providers whatever they claimed was “reasonable.”

Today, that arrangement is being destroyed. The old system’s generosity led too many patients, physicians and hospitals to regard medical insurance as the equivalent of a credit card whose bill never came due. When health-care costs soared above even the high general rate of inflation, those who did have to pay the tab–the government and private businesses–finally took the credit card away.

The clearest symbol of this change was Medicare’s decision in 1983 to begin paying hospitals set fees for each of 468 diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) rather than reimbursing hospitals based on their individual costs. On average, Medicare accounts for about 40 percent of a hospital’s revenues.

In a like manner, most private insurers are vowing to pay only for what they believe is reasonable, just as in any other business transaction.

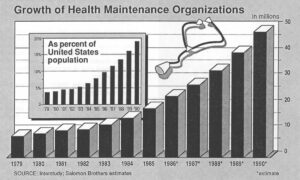

Unable to raise prices freely, physicians and hospitals have instead turned on each other in a kind of “care wars” for survival. At a time when the average hospital stay is getting shorter and an oversupply of physicians is increasing, the challenge is to retain current paying patients while capturing new ones. Ammunition has included the repackaging of existing services, in the manner of women’s centers and sports medicine clinics, and the addition of promising new services, such as outpatient surgery centers and drug treatment programs.

Sometimes those new services require a substantial investment. For instance, Humana Inc.’s artificial heart transplant program is only one of a group of “centers of excellence” the hospital corporation has established in cardiology, diabetes and burn treatment around the country. Dr. Thomas Moore, Humana’s vice president of medical affairs, says the specialties involved were picked with one eye on medicine and another on business.

“The question was what kinds of patients would legitimately need hospital care in spite of these [competitive] pressures in the 1990s,” Moore says.

The Humana effort pales into dull traditionalism, though, compared to the tack taken by Republic Health Corp. The Dallas-based hospital chain is a leader in “boutique medicine,” or specialty niches in health care. To pull in paying customers, Republic “peddles its wares the way Procter & Gamble pushes its soap,” Fortune magazine noted.

Republic hospitals put pizzazz into foot care with “Step Lively” (get a $20 gift certificate towards new shoes after foot surgery); into eye care with “Gift of Sight” (a $50 certificate towards new glasses after a cataract operation); and into sexual dysfunction with “Impotency Solutions” (a $150 discount certificate good towards, among other things, a new…penile implant.)

“People respond to a discount,” explains Richard Gordon, regional marketing manager of Republic. Even for such a sensitive and serious problem as sexual dysfunction? “Hell, yes.”

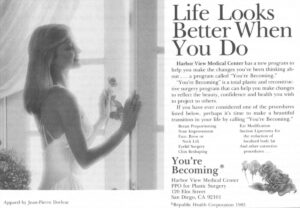

And they respond to ads. One of Republic’s most successful promotions has been the “You’re Becoming” plastic surgery program for women that offers everything from face lifts to body contour surgery. The model featured in the ads, which proclaim, “Life Looks Better When You Do,” makes Bo Derek look like an 8-1/2. In a year and half, the ad drew 4,600 responses in Houston alone.

Donna Yardley, 26, says she’d considered having her breasts enlarged for five or six years but didn’t decide to go ahead with it until learning about the Republic program. Part of the attraction, she said, was the guaranteed price and the easy payments for the $3,500 procedure. Republic offers low-interest financing through General Electric Credit Corp., better known for its loans for dishwashers and refrigerators.

“The biggest change it made for me was the way I looked in my clothes,” says Yardley (not her real name), who stands 5 feet, 5 inches tall. “People who didn’t know I had the operation said, ‘You lost weight.’ A woman loves to hear that…My self-confidence really escalated.”

In Chicago, a small, free-standing surgicenter called Urban Health Services Ltd. has used 30-second TV spots to zoom from 4,000 procedures in the year ending Aug. 31, 1984 to an expected 12,000 procedures by Aug. 31, 1987. The surgicenter now promotes 12 different operations under names such as the Center for Cosmetic Surgery, Lakeshore Laser Institute (for hemorrhoids), and the Eye Care Institute. Most of the work is covered by insurance.

Urban plans to spend $1.8 million on advertising this year. By way of comparison, a national survey found that the average hospital spent about $102,000 on advertising in 1986, up 60 percent from the year before. The Urban budget dwarfs even what Republic will spend on its flagship Houston facility. Says an Urban spokesman, “Rather than invest in consumer studies, the company finds it more economical to develop a surgical specialty and advertise it. If there is a good response, it is added to the list of…regular procedures. If not, it is eventually dropped from the ad schedule.”

No ads have accompanied a second path to profitability pursued by a number of hospitals: they have established limits on free care. Some have also limited care for Medicaid patients. (Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that covers some of the poor. Payments vary by state, but reimbursement is usually much less than private insurance or Medicare.) The limits are often informal, but they are real and widespread, and they show up repeatedly in interviews with physicians and with hospital managers.

“From the perspective of paying patients, the newly-emerging buyer’s market in health care will be a delight,” says Prof. Uwe E. Reinhardt, James Madison Professor of Political Economy at Princeton University. -[However] the American public must be prepared to pay explicitly for the health care of poor fellow citizens or let the latter wither on the vine

Adds Reinhardt, “We are now firmly embarked on a march towards two-class medicine.”

Research being done by Northwestern University’s Center for Health Services and Policy Research is among the first to show clear evidence of this splintering. The center is analyzing actual patient data provided by hospitals as part of a three-year national study of hospital strategies.

The data show that “competition has had a positive effect on the number of services offered” the middle-class, says Prof. Stephen Shortell, the principal investigator for the study. For the poor, though, competition means hospitals “are less likely to offer charity care.”

However, Carol McCarthy, president of the American Hospital Association, insists. “There has not been any stepping away from the indigent care issue on the part of hospitals.”

Perhaps. But what, then, of the epidemic of “dumping” highlighted by medical reports during the first half of 1985? Private hospitals were repeatedly caught transferring uninsured patients to public hospitals in circumstances that can only be described as barbaric.

For example: a 21-year-old in critical condition was denied entry to the burn unit of a university hospital in Nashville. A pregnant woman in Wyoming, diagnosed as having complications, bled internally for a month as she and her husband scraped up the $500 down-payment an investor-owned hospital demanded before surgery. A Dallas woman was transferred in the middle of labor after mentioning she had no insurance. A stabbing victim in San Francisco was refused care at several private hospitals before dying at the public one. And the list goes on.

Comments Elliott C. Roberts, administrator of New Orleans’ Charity Hospital, “To be medically indigent in a competitive system…is tantamount to being an outcast.”

There is some evidence that dumping has abated, though it certainly hasn’t disappeared. No one knows for sure, however, because there is no one tracking “dumping” nationally. If it has declined, credit must go to publicity, lawsuits and new federal legislation prohibiting transfers of unstable patients. Dallas’ Parkland Memorial Hospital has tracked the problem for itself and reports that dumping appears to have lessened after passage of a Texas law regulating emergency transfers.

On the other hand, Parkland’s neighboring hospitals may simply have been discouraged by the reputation of Parkland’s president, Dr. Ron Anderson. Anderson was a major backer of the antidumping measure. He helped prod the state legislature into action by cooperating with 60 Minutes in an episode featuring tapes of doctors telling Parkland they were transferring critically-ill patients because they lacked insurance.

The pain and discomfort routinely visited on patients like car accident victim John Thompson, the Cook County patient who was transferred with “stable” compression fractures of the spine, has sparked no public outcry. Both private and public hospitals say the publics are in existence to take these patients. Ignored in this cozy arrangement is that the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals prohibits any transfer of patients for an economic reason. There is no record, however, of any hospital losing its accreditation because of a transfer.

Parkland’s Anderson explains the lack of a public outcry by saying, “I don’t think the American people are ready to see people die on the streets and walk over them. [But] as long as public hospitals keep them out of sight, it’s not on their conscience.”

There are more and more people to keep out of sight. In 1984, almost one in six Americans–or a little over 35 million people–had no medical insurance, according to the Census Bureau. That’s up 22 percent from five years before. An estimated 65 percent of those without medical coverage were working or were the wives, husbands and children of workers. Many small businesses and service businesses do not provide health insurance.

Charles Gilmore, 32, works for a window cleaning company that employs 30-40 people. “No one that I know [at work] has health insurance,” says Gilmore, who’s come to Cook County Hospital’s outpatient clinic after three days of a cough and cold. Gilmore is fortunate–he waited only 3-1/2 hours to be seen after arriving at 5:30 in the evening. A five-hour wait is not uncommon.

Mary Allen, 47, seeing a doctor about chest pains, usually comes to the hospital’s emergency room at 5 or 6 in the morning to keep the wait down to about 2 hours. Allen has a temporary job filling orders for a large cosmetics firm. Like a growing number of companies, hers employs part-time workers to keep costs down. Allen has no health insurance.

For the working poor, Medicaid gives little medical aid. In fact, Reagan budget pressures helped reduce the percentage of poor people covered by Medicaid from a high of 63 percent in 1975 to about 46 percent in 1985.

Suffering the most may be victims of chronic conditions. Those “dying in the streets” after all, command attention. Not so the sufferer from high blood pressure, diabetes or sickle-cell anemia. At big public hospitals, a visit with a doctor is rationed by waiting. At Cook County, officials estimated that 8 to 10 percent of the patients simply give up and leave.

“People just grow to accept it as part of the process,” says Dr. Ted Brockett, the attending physician running Cook County’s ambulatory screening clinic one evening. “It’s strictly patch up and send ’em out.”

Community health clinics are similarly overwhelmed. At Los Barrios Unidos Community Clinic in west Dallas, Dr. Kathy Simon acknowledges, ‘We turn away lots of people.” The clinic has two doctors and a nurse practitioner: it has neither the funds nor staff to remain open long hours. So, except for emergencies, it’s first-come, first-served for 25 people in the morning and 25 people in the afternoon.

Unfortunately, says Simon, “a lot of problems that are really medical emergencies that shouldn’t wait a few days are not picked up by a receptionist.” For instance, says Simon, “I’ve had at least three diabetics with foot ulcers” who failed to convince a receptionist of the seriousness of the problem. After losing several days at work because of immobility, the patients finally got treatment.

Dr. Ron Anderson sums up the dilemma of the new medicine this way: “Never in human history has economic competition resulted in the just distribution of scarce and life-sustaining resources.”

Anderson should know. To defray costs of the uninsured, Parkland is competing for paying patients with a special floor featuring a few more amenities and better nursing service. And to appease the university physicians upon whom it depends for staff, Parkland is helping to build a private hospital next door that will give its staff a chance to have private patients, too. Other public hospitals have also taken steps to attract paying customers to offset some of the cost of the medically indigent.

If there are clear villains here, they are hard to find. Should hospitals, especially tax free ones, be more responsive to the uninsured? Probably. But as the nun who heads a large Catholic chain puts it, “There’s no mission without a margin.” (That’s profit margin, of course.) Naturally, doctors can’t be expected to provide their services for free, either.

Should insurers, HMOs and businesses be condemned for driving a hard bargain on medical prices? Perhaps, except consumers don’t expect to pay a higher hotel bill as a way of funding the homeless or a steeper restaurant tab in order to feed the hungry.

The government is an obvious bad guy. But the government, of course, is elected by all of us.

A number of solutions have been proposed to the indigent care problem, including various special funds and reforms of Medicaid and Medicare. None will go anywhere until the middle-class remembers that the extra medical services and conveniences that competition is bringing them are in part resulting in services and conveniences being taken away from others.

“The social contract is not a set of promises or laws. It is a process,” writes Emily Friedman, a longtime activist in the indigent care arena. “We all seek protection from the random violence of life..

“We have to protect each other because we don’t know who’s next.”

©1987 Michael Millenson

Michael Millenson, a reporter on leave from the Chicago Tribune, concludes his reporting on the deregulation of the American health-care system.