Several days a week, Dr. Harold Jensen pores through a stack of medical records from Ingalls Memorial Hospital, a 704-bed facility in a working-class Chicago suburb. Review nurses have used guidelines to winnow the patient charts down to those which may present problems. However, as part of the final peer review process by which physicians ultimately judge each other, it is Jensen’s job to decide what are allowable exceptions to the rules and what are medical errors.

Though Jensen is an experienced reviewer, he readily acknowledges the difficulty of monitoring the 340 staff physicians who admit more than 20,000 patients annually. By necessity, only a limited number of medical charts can be reviewed in depth. With too much detail, he says, “you get swamped by the numbers.”

That should change soon. Ingalls Memorial is installing a computer system that, for the first time, lets reviewers compare physicians to each other according to objective guidelines that measure just how well their patients are doing. The key to the new system is a method, still controversial, that classifies patients according to the severity of their illness. In doing so, it strips away a standard explanation of physicians for why their patients seem to have higher rates of complication or death than the norm: “My patients are sicker to begin with.”

“We are making [quality assurance] an objective process,” says Jensen, chairman of the Illinois chapter of the American College of Utilization Review Physicians. “We’re just imitating what’s been done in industry.”

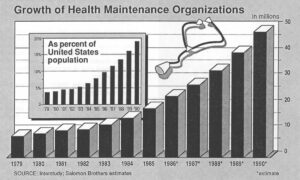

Ingalls Memorial is not alone. From hospitals to health maintenance organizations (HMOs) to medical professional societies, industrial procedures for quality control are increasingly being studied as a model for measuring medicine. Alongside the usual paeans to the “art” of medicine, scientific publications such as the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) have begun directing reader attention to such unlikely sources of guidance as the American Society for Quality Control, a predominantly industrial trade group.

Once virtually God-like in their independence, physicians are now being urged to pay attention to the smokestack definition of quality: “conformance to requirements.”

“The single most important thing that American medicine and its societies at this time should do is define quality indicators and follow them,” says Dr. George Lundberg, the AMA’s vice president for scientific affairs, and JAMA’s editor.

Adds Dr. Alan Brewster, president of MediQual Systems Inc., the designer of the computer system being used by Ingalls Memorial, “Individual doctors have to lose autonomy to move to the next level [of quality].”

Such talk represents an extraordinary change in the role of physicians. Less than a century ago, the primary role of doctors was as hand-holder and comforter. Only the spread of such “miracle drugs” as penicillin, after World War II changed the role to that of healer. Now, another major change is brewing. As the American health-care system moves from a regulated one, in which individual physicians and hospitals had near total freedom, to a competitive system, in which those who buy and finance health care have the upper hand, the role of the doctor is changing, too.

As the prime players in an industry on which Americans spend more than $1 billion daily, physicians are going to be responsible for bottom-line results.

“When you get to outcome measurements, it’s not going to matter who you are,” promises Dr. James Prevost, the director of research and development for the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals (JCAH), a not-for-profit group run by representatives of physician and hospital professional societies. “You’re going to have to put up or shut up.”

A major shift of policy by the federal government in paying for Medicare is responsible for a great deal of the change. After years of reimbursing hospitals based on whatever their individual costs were, Medicare, in October, 1983, instituted a “prospective payment” system using fees set in advance for each procedure, or diagnosis-related group (DRG). Hospitals that could provide care for less would profit; those which cost more would lose money.

At the same time, the business community increasingly pressured doctors and hospitals to keep their costs down by using middlemen, such as HMOs and utilization review consultants, to “manage” care. Again, “cost-effective” providers would get contracts for care; others wouldn’t.

On one level, at least, the tactics seemed to work. The Medicare DRGs are calculated on an “average” length-of-stay for each illness. Hospitals which beat the average make more money. In 1985, hospital inpatient days reached a record low after a 1984 rate that was itself a record bottom. Outpatient visits, meanwhile, increased almost 5 percent from 1984 to 1985 and jumped more than 9 percent for the first quarter of 1986 when compared to the same quarter of 1985, according to the American Hospital Association.

Unfortunately, no one can say for sure whether the changes came from efficiency or from just plain cutting corners in care of the privately-insured and of the 30 million elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries.

Jeffrey Merrill, who helped design the prospective payment system as associate director of policy for the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), puts it this way, “The system is becoming more Outpatient oriented, and there’s no way we know of to measure quality on an outpatient basis.”

Indeed, notes Merrill, now a vice president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which specializes in health care policy, “we implemented…the most major piece of legislation ever passed in this country, with the exception of Medicare and Social Security, and we knew it could have some effects in terms of quality. We could have looked first [but] nobody cared.”

“Nobody knows how to define, in a reproducible manner. quality,” confirms Dr. James Todd, a surgeon and senior deputy executive vice president of the AMA. “Quality is kind of like pornography. I can’t define it, but I know it when I see it.”

But if quality is not definable, then doctors and physicians are in a poor position to resist those who claim that large portions of the money spent on medical care is wasted on unneeded tests, unnecessary operations and overly-long hospital stays. On the other hand, those who would hold physicians responsible for the results of their care can hardly do so if the final test boils down to a difference of opinion among competing doctors.

There are those, like Todd, who grumble that “you’ll do all this documentation and measurement” simply to find what the “average physician” knew all along. Nonetheless, groups ranging from the AMA to the Washington Business Group on Health, a national organization of major corporations, are working feverishly to come up with what will be nothing less than national standards for medical care.

Dr. Dennis O’Leary, who assumed the presidency of the Joint Commission last April, is blunt about his group’s aims. Says O’Leary, “We have an ability not only to set standards but to enforce them.”

He could be right. The JCAH accredits about five-sixths of the nation’s community hospitals. Its stamp of approval allows hospitals to be reimbursed by Medicare without undergoing a separate government certification. Medicare patients account for about 40 percent of an average hospital’s revenues.

The JCAH recently announced it will evaluate the outcome of care when it grants its seal of approval to hospitals. It hopes to have the new standards in effect by 1991. The next step is applying the same criteria to nursing homes, HMOs and ambulatory care centers, all of which the JCAH reviews to a lesser degree. It is a formidable task.

The vagueness of today’s standards complicates the job. Astonishingly, at least to a layman, there is no accepted “baseline” of medical quality measurements. For instance, a modest program by the Maryland Hospital Association to get seven diverse hospitals to share enough data to agree on what a “normal” rate of infection should be or what rate of Cesarean-section deliveries is worrisome is being hailed as a pioneering effort with national implications.

Similarly, a subject of hot debate among physicians today is whether there is justification for geographical variations in care; that is, treating back pain differently in Maine versus California, or even differently within different parts of, say, Maine, itself.

Still, the movement towards standards derives part of its strength from an increasing amount of research showing that essentially good doctors are doing bad things to good people. For instance, severity-of-illness adjustments are forcing physicians and hospitals to confront an open-secret: hospitals which perform a high volume of a particular surgical procedure generally have a lower mortality rate than low-volume hospitals; that is, even for surgeons, practice makes perfect.

For example, a hospital studied by two University of California, San Francisco, researchers did a relatively small number of cardiac catheterizations, a complex diagnostic procedure for heart disease, possibly because it lay within a half-hour’s drive of 12 other hospitals doing the same procedure. Instead of having an expected 6 deaths among its 161 cardiac catheterization patients, 24 people died.

After publicity about similar mortality problems with its cardiac surgery units, the Veterans Administration decided to close a third of them.

Perhaps even more disconcerting is research by Dr. William Knaus of the ICU Research Unit at George Washington University Medical Center. Knaus studied the intensive care units (ICUs) of 13 major hospitals, including some of the most famous names in American medicine. After adjusting the outcome of patient care to reflect the severity of illness, he discovered hospitals with, in one case, a death rate as much as 58 percent higher than expected. At fault was not a lack of high technology or a university affiliation.

Instead, Knaus wrote, in an explanation worthy of “The One-Minute Manager,” doctors and nurses in the bottom-ranked hospital worked in an “atmosphere of distrust.” At the top-ranked hospital, with results 59 percent better than expected, physicians and ICU nurses worked as a team, and the nurses had authority to act on their own in case problems suddenly arose.

How all this research will be put to use remains to be seen. The federal government claims to be keeping an eye on quality through its contracts with private, not-for-profit groups, called “peer review organizations” (PROs), that it set up along with the prospective payment system. At first the groups were told to make sure hospitals weren’t trying to keep patients in the hospital for extra days of care in order to protect profits. But after evidence appeared that some patients were being discharged too early the PROs were ordered to focus on quality, not just cost. That new focus on quality instead of utilization is just being implemented in the current PRO contracts up for their scheduled two-year renewal.

Though Medicare sets its DRG payments based on an “average” case, a hospital is expected to have some cases which cost more and some which cost less. A facility would, of course, make more money if all its patients were discharged more quickly than the “average” case.

Some health-care “buyers” are also eager to serve as quality watchdogs. Honeywell Inc. recently unveiled a set of standards that gives the computer maker the right to evaluate providers based on the outcome of care of employees. That kind of “conformance to specifications” tone is a far cry from the way health-care buyers have usually treated providers.

“I don’t want to operate under the guise of giving my people a quality product when I haven’t had time to assess it,” explains Laird Miller, Honeywell’s corporate director of health systems and a former administrator of a physician group practice. “Changes in health status are probably the ultimate measures.…Ninety-three percent of your heart transplant patients will live one year or I will not pay you for the services you render.”

If all this seems like a Golden Age of Medicine is about to unfold for patients, a closer look shows there is both more and less here than meets the eye. One definition of quality medicine certainly has to include access to it. Unfortunately. no one is sure how to find care that was denied.

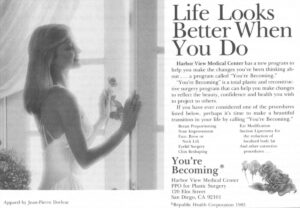

For instance, in north suburban Minneapolis, Kathy Tender brought her son Scott Potthoff to an orthopedic surgeon to be treated for the multiple problems resulting from his cerebral-palsy like condition. Dr. Timothy Mjos, the, orthopedist, recommended that Scott, now 8 years old, be referred to a local specialty children’s hospital. The hospital, however, had no contract with the HMO to which Tender belonged. Despite a letter from Mjos to the medical plan saying the care was needed, the HMO refused to pay for the referral.

Mjos and Tender both acknowledge they cannot point to any specific way in which Scott was harmed by not going to the specialty hospital. Still, Tender, who has since dropped the HMO, is bitter.

Says Tender: “I wanted the privilege of having him evaluated. They call themselves a health maintenance organization. yet they don’t want to pay for…an evaluation that might have benefited Scott.”

There are other problems darkening the lenses of the optimists. For instance, the Reagan administration continues to squeeze Medicare funding on the assumption, more a matter of faith than information, that there’s still plenty of fat left in the system. Though the PROs have added “quality” to their “cost containment” mission, their budget has not been increased in the same way, say, as if they had been deputized to find teen-aged drug users.

Walter McClure, director of the Center for Policy Studies, speculates that Medicare’s dilemma over quality just doesn’t make big enough headlines.

“The Federal Aviation Agency works because when it fails it kills people a planeload at a time and that’s big news. Medicare kills people one at a time,” McClure says.

Though review often requires a sophisticated staff, many PROs, pay their freelance physician reviewers much less for the time spent on reviews than the same time would earn in private practice. While some physicians accept the cut as the price of civic responsibility, the bulk of reviewers tend to be doctors just starting out or those in the waning years of active practice.

The job has another drawback: “private” or not, PROs are widely regarded as the outstretched arm (or, perhaps, finger) of an intrusive government; participating physicians can find themselves social outcasts.

Similar problems of physician pay and demographics dog the JCAH, though its survey teams suffer no social stigma. Still, while many hospitals credit JCAH surveyors with sparking real change at their institution, others call the organization a paper tiger. Barry Bader, a Maryland consultant to hospitals on quality assurance, says the JCAH mostly reviews a hospital’s own documentation of its quality efforts.

“Hospitals are able to appear to be complying by preparing for the survey rather than actually doing the job,” Bader charges. “It’s like cramming for an exam. It doesn’t mean you’ve mastered the course.”

Responds a JCAH spokesman, “I doubt hospitals could provide evidence they complied with the standards during the whole three-year period prior to the inspection” unless the compliance was real.

Moreover, groups such as the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) argue that oversight of medical care needs to be done by “a neutral, publicly-accountable entity, which the JCAH has never been,” in the words of Jack Christy, a senior policy analyst for the AARP.

Meanwhile, the big buyers of health care have yet to earn their stripes as protectors of workers. In Rockford, Ill., for instance, a group of employers hired a consultant in a widely-publicized effort to contract with only “quality” hospitals and physicians. The “quality” providers who won the contract turned out to be those offering the best price, says Marilyn Plomann, an associate in the consulting firm used by the corporations.

“They didn’t really end up evaluating the hospitals. They said they were looking for quality but they weren’t. They were looking for a discount,” Plomann says.

Similarly, Health Data Institute of Lexington, Mass., got the hostile intruder treatment from the U.S. Air Force after finding problems at Air Force hospitals.

“When you find problems, it’s explosive,” says Dr. Paul Gertman, HDI’s founder.

“I see a lot of rhetoric and little results,” says Dr. Robert Brook, a Rand Corp. researcher and a professor of medicine and public health at the University of California, Los Angeles. “if you’ve got competition, you need to have information on quality, [but] there’s no money in the public sector to do research in quality, measure quality and present information.”

Nevertheless, problems with traditional peer review are helping so-called “objective” measurements, even though the state of the art may be cruder than desired. The process of concerned professionals critiquing their peers remains the cornerstone of medical quality assurance; the commitment of good doctors, in fact, is; undoubtedly the most important factor in the generally high-quality medical care in this country. But the peer review process is an increasingly troubled one.

A growing number of physicians disciplined by their peers have traded the tight smile of one swallowing disagreeable medicine for the loud screams of lawsuits against everyone involved. Peer review has become entangled in litigation about everything from malpractice to antitrust. Small wonder that caution has replaced candor in a growing number of hospitals.

Apart from litigation, there’s the problem of referrals. Dr. Donald Hanscom, a gastroenterologist at suburban Chicago’s Hinsdale Hospital, discovered that family practitioners did not uniformly appreciate his efforts to reduce overuse of a procedure that employs a special scope to examine the inside of a patient’s stomach. While lucrative financially, the procedure is done too frequently, Hanscom says.

“My surveillance…has cut off about 30 percent of my referrals from family practitioners,” sighs Hanscom, who is president of Hinsdale’s medical staff. “Some of them have decided, ‘The next time I need a gastroenterologist, I’ll call somebody else.’ “

Peer review at its best can produce superb medicine. The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., has fine-tuned the process on the way to becoming the most famous medical brand name in America.

Dr. W. Eugene Mayberry, chairman of Mayo’s board of governors, freely admits that “American medicine is passing from a cottage industry to big business.” And with its recent merger with two local hospitals it long controlled, the Mayo Clinic certainly fills the bill. Its army of 850 staff physicians and an equivalent number of medical residents–not to mention 40 students at the Mayo Medical School–is but part of an empire with 14,000 employees, $750 million in annual revenues, a satellite clinic in Florida and another set for Arizona.

Yet for all that, the Mayo Clinic retains a dedication to patients that combines what is often called quality of medical service with quality of medical care. To long-time patients like Ernest and Dorothy Richardson of Mincing, Wisc., who’ve been coming to the clinic for 45 years, it remains the place where “they make you feel like they’re trying to help you,” in the words of Ernest Richardson, 80.

“We have a doctor when we go to Mayo,” adds Dorothy, 74.

Physicians at Mayo earn a salary; there are no incentives or bonuses for the amount of care given or not given. There is constant review of each other’s medical records.

“You have to accept the fact you really do work as a team. There are no prima donnas,” says Dr. Fred T. Nobrega, director of the Mayo Clinic’s health care studies unit and a 20-year clinic veteran. The esprit de corps includes pride in making an accurate presentation of medical findings to one’s peers, even if it means owning up to an error, Nobrega says.

“If you present things in an inaccurate way, it’s an intangible mark against your professional pride,” he says.

For physicians whose pride is not enough to maintain standards, other pressures are sure to come–and not just from peers.

“Bad medicine is what’s costing us a lot of money, not good medicine. If you cut out unnecessary medicine, there would be no cost crisis,” says Charles Inlander, head of the People’s Medical Society, a consumer group based in Emmaus, Pa. “We as consumers are not going to tolerate second-class care.”

Says Carolyne Davis, former administrator of HCFA and now a consultant for Ernst & Whinney, “It’s only a step away before we see Hospital Consumer Digest or Physician Consumer Digest…that looks at real outcome measures.”

©1987 Michael Millenson

Michael Millenson, a reporter on leave from the Chicago Tribune, is chronicling the deregulation of the American health-care system.