Elizabeth Olson thinks the day she joined the “Senior Care” program of Share-Minnesota was one of the luckiest of her life. She told her story in a full-page newspaper ad Share ran to recruit elderly members for the special Medicare version of its HMO.

“In the past couple of years, I’ve had surgery, seen a lot of specialists and had months of chemotherapy. Share picked it all up,” says Olson of the Minneapolis-based health maintenance organization (HMO).

She continues, “If they hadn’t paid for everything, I’d probably have a lien against my home. I would’ve been wiped out!”

Mary Jane Bohnen has a different point of view. She told her tale in an investigative report broadcast by WCCOTV in Minneapolis. Her son, Daniel, had both eyes pierced by shotgun pellets in a hunting accident. Share paid for the first two operations, which unsuccessfully tried to save his left eye. On the day a crucial operation was set for the right eye, though, the Share business office called.

Recalled Mrs. Bohnen, “(They) called me as I was just about ready to leave to take Daniel to the hospital, and they wanted to see Daniel. And I explained to her that he was scheduled for surgery….The ophthalmologist at Share examined Daniel and assured me that he did not need that surgery at this time…”

Nine days later, when Daniel saw a consultant arranged for by Share, it was too late: the vision in his right eye had deteriorated, leaving him legally blind. Mrs. Bohnen said she was told Share delayed to try to save money. Noreen Suntrup, director of corporate public relations for United Health Care Corp., which now owns Share, denies the charge and says the proposed operation would likely have failed anyway.

However, without admitting guilt, Share paid the Bohnens $1.2 million to settle a lawsuit against it and its doctors. An HMO spokesman says it settled at the behest of its physicians’ insurance company in order to avoid the risk of a trial.

Together, the stories illustrate both the rewards and perils Americans are facing as the way medical care is delivered in this country undergoes a radical change.

Traditional fee-for-service medicine is shrinking rapidly towards oblivion, a victim of its laissez-faire attitude towards cost. In its place is arising a “managed care” system based on the bottom-line calculation that competition will result in consumers getting better quality medicine at a lower price. The linchpin of that new system is the health maintenance organization, or HMO.

HMOs trace their origins to the idealistic “prepaid group practices” that arose in the late 1920s to provide farmers and blue-collar workers with good medical care in return for a small, fixed payment–in the beginning, literally pennies a day. The groups never caught on big, though, even after a 1973 law required large employers to offer “federally-qualified” plans if they were asked to do so. A federally qualified plan offers a certain package of benefits, including well-baby care, mental health coverage and vision care.

But HMOs have boomed in the 1980s as “competitive medical plans.” Gone are the veiled overtones of socialism (or worse). Corporate America is rolling out the red carpet for HMOs as health and health cost maintenance organizations.

For one thing, studies show that HMOs can provide quality care for 10 to 40 percent less than traditional fee-for-service medicine, mostly by hospitalizing patients less frequently. At the same time, benefits managers can simply compare the price and services offered by various health plans rather than attempting the hopeless task of trying to control individual hospitals and doctors.

Explains Douglas Sherlock, an analyst with the investment banking firm of Salomon Brothers, “Health maintenance organizations ‘package’ health care in units that lay people can understand.”

In 1982, meanwhile, the federal government began allowing HMOs to enroll Medicare patients on an experimental basis; it made the option permanent in 1995. State governments, among them those in California and Wisconsin, also gave renewed attention to HMOs as a way to control the cost and quality of Medicaid.

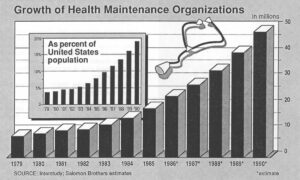

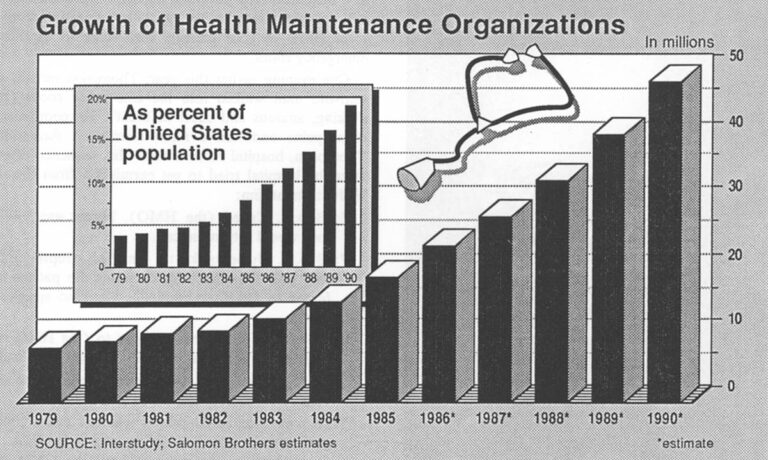

HMO membership figures reflect the new attitude. In mid-1980, there were 9.1 million Americans in HMOs, or about 4 percent of the U.S. population, according to InterStudy, an Excelsior, Minn., research group. By the end of 1984, HMO enrollment had spurted to 16.7 million people, or 6.4 percent of the population. Only one year later, enrollment was up another 26 percent to 21.1 million, or 7.9 percent of the population, a record annual gain.

“We are likely to see half of the U.S. population in price-competitive health plans by the early to mid 1990s,” predicts Dr. Paul Ellwood, founder of InterStudy and the originator of the term “health maintenance organization.”

But the importance of HMOs lies in far more than just the soaring enrollment figures. HMOs are a closed system of care, limiting consumer choice in return for assuming the financial risk for care. That risk is what gives doctors and hospitals affiliated with HMOs an incentive to practice cost-effective medicine. Partly in response to competition from HMOs, traditional forms of health insurance are being transformed into the new “managed” variety.

Medicare’s prospective payment system, for instance, uses 468 diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) to set what become, in effect, “unit costs” for hospital care. Blue Cross/Blue Shield plans, commercial insurers and self-insured corporations have introduced new “management” features such as requiring that a doctor get their clearance before hospitalizing a patient. Hybrid groups called “preferred provider organizations” (PPOs) have sprung up in an attempt to combine HMO-type controls on the providers with a wider choice of doctors and hospitals for the patients.

“HMOs are the paradigm of the health-care delivery system of the future,” concluded Peter Fox, a consultant with Lewin and Associates.

It is a remarkable change. In 1986, a majority of Americans will, for the first time, receive their health care from some sort of “managed” plan, according to Kenneth Abramowitz, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. He expects that figure to climb to 90 percent by as early as 1990.

There is considerable evidence that the old payment system has been responsible for many Americans suffering needless medical tests, useless surgery and bloated hospital stays. And the new “managed” care has prompted many doctors and hospitals to upgrade the quality of their service with such patient-oriented steps as longer office hours or satellite clinics located near residential areas.

Still, the new button-down medicine raises some troubling questions of its own.

“The problem is, there’s a fine line between efficiency and under-service that’s detrimental to the patient,” points out Cynthia Polich, executive vice president of InterStudy. “It really falls to the physician to make sure that they’re practicing efficient, conservative medicine, not shlocky medicine.”

Medicare’s DRG payment system illustrates some of the problems that can arise when those who directly provide care try to be businessmen, too. DRGs represent averages; that is, some patients receiving, say, a coronary by-pass procedure will cost a hospital more than the allotted payment while others will cost less. On average, though, an efficient hospital should make money at Medicare’s current price.

But there have been widespread reports of hospitals and doctors using the DRG calculations as maximums, either deliberately or because of confusion. Michele Adamich, a registered nurse in Minneapolis, recalls how physicians reacted in one hospital where she worked.

“They would write in their progress notes or in the (patient’s) charts, ‘Have to be discharged because of DRGs. Have to be discharged because out of money.’ “

“Almost every force being exerted on doctors today is pushing them away from the professional aspects of what they do and toward the business aspect,” acknowledges Dr. Harrison L. Rogers Jr., immediate past president of the American Medical Association (AMA).

These forces “tend to make the doctor think first about the financial aspects of the needed services and whether the patient or a third party will be willing, or able, to pay for them,” Rogers says.

Even some businessmen worry whether the pendulum might swing too far.

“We’ve accused the doctor of playing God for years now,” muses Jack Milligan, director of compensation and benefits for Garrett Corp., a Los Angeles-based aerospace firm. “How much of that role have we assumed?”

Sally Thompson has one answer. Thompson (not her real name) is a registered nurse who oversees admissions at a busy Louisville hospital. She says it is becoming difficult for physicians to get quick authorization from one local HMO to treat patients who come to the hospital emergency room.

One evening earlier this year, Thompson recalls, a 42year-old man walked into the emergency room (E/R) shaking, anxious and short of breath. He complained of chest pains and had a rapid heartbeat. According to Thompson, hospital records show this sequence of events after the hospital tried to get permission from the man’s HMO to treat him:

6:58 p.m. Called (the HMO). Nurse was told that they would return the call.

7:08 p.m. Nurse spoke to (an HMO representative) who said the HMO doctor wants the patient transferred to (another hospital). Gave no specific reason.

7: 10 p.m. E/R supervisor spoke to (the HMO representative), who said the HMO would call back.

7:25 p.m. The HMO called and asked for the supervisor.

7:26 p.m. The HMO said it was not authorizing the patient to be admitted and treated in the E/R. (The representative) promised to have the HMO doctor call back.

At that point, says Thompson, “we already had (the patient) in the back working on him. We don’t take any chances.” She suspects the request for a transfer came because the HMO has a better contract with the other hospital.

Meanwhile, the hospital E/R physician sent a nurse to get the patient’s chart away from the telephones so he could record the treatment.

7:30 p.m. The HMO doctor called back.

7:33 p.m. After talking to the E/R supervisor, the HMO doctor authorized treatment.

After being given heart medication, the man was discharged around midnight.

HMO advocates rightly point out that fee-for-service medicine has its horror stories, too. They assert that their critics often blur the line between patient inconvenience and real medical danger. In addition, they note that a study of 20 years of medical literature comparing HMOs with fee-for-service medicine found that the care at HMOs was almost always equal or better.

Yet the years covered by that study, 1958 to 1979, comprised a period when most HMOs were consumer co-ops and not-for-profit partnerships or corporations. Their competition consisted of individual doctors or insurance plans which paid claims and didn’t worry about costs.

From 1979 to 1985, the number of HMOs more than doubled, to 480 plans, according to InterStudy. Most of these now face competition from other HMOs and from various managed care programs.

The industry’s structure is also changing. In 1985, for the first time, for-profit plans outnumbered the not-for-profits, though the latter still held a comfortable membership edge. A number of not-for-profit plans have converted to for-profit status or set up for-profit subsidiaries. (For example, a Harvard Community Health Plan Subsidiary is partly owned by the plan, a venture capital firm and American Can Co.)

One lure of for-profit status is easier access to capital. HMOs at present earn about a 25 to 50 percent greater return on invested capital than other companies in the service sector, notes Peter Grua, an analyst at Alex Brown and Sons.

InterStudy estimates that 99 new HMOs sprung up in the last six months of 1985 alone. Industry observers are beginning to worry about a shortage of experienced managers. Between 1973 and January, 1986, for example, federal statistics show that 30 HMOs merged or went out of business for financial reasons.

Laments Jonathan Weiner, a professor of health policy and management at Johns Hopkins University, “The health-care system in which the earlier consensus on HMO quality was developed bears little resemblance to today’s evolved system.”

Some HMOs and PPOs require nothing more than a membership fee from a doctor who wishes to participate. Others accept a doctor who belongs to a participating hospital’s staff, relying on the hospital for screening. Others, especially large group practices of physician partners, ask tough questions.

“One of the things we’re proudest of is we fire doctors,” says Dr. Charles Jacobson, a partner and manager of the Park Nicollet Medical Center in Minneapolis. The group is part of an HMO and also treats fee-for-service patients.

Plans increasingly differ, too, in their coverage. “Federally-qualified” HMOs will offer a certain minimum package of benefits relatively generous in its size. Other plans carry no such burden. Benefits vary locally even in “national” plans, such as those affiliated with the Blue Cross/Blue Shield or large insurers.

Subtler differences don’t always show up in the benefits list. The care a pregnant woman gets, for instance, might vary depending on what plan she joins and how assertive she is. Her care could include seeing physician assistants and a doctor; a midwife only; a midwife only, then a physician at the time of delivery; or a physician only.

Of course, traditional insurance can contain unexpected gaps, too. But HMOs seem to present themselves differently, more “as a large physician,” in the words of Dr. Gail Povar, an internist at the George Washington University Health Plan.

She adds, “(The HMO) purports to provide care, not just a payment mechanism. (But) if the HMO…’doctors’ the benefit package so as to leave out certain kinds of care, or to create barriers to certain kinds of care, the physician may find himself in the position of insisting that the patient get care which the physician’s institution refuses to pay for.”

The new managed-care medicine also contains significant variations in how doctors and hospitals are paid, differences of which patients are often completely unaware. Some HMOs employ doctors directly on their staff. Others give lump payments to a group of doctors and let the physicians allocate money for care. Some “preferred provider” groups simply discount a doctor’s fee, leaving some wondering whether a physician will increase services to maintain his income.

An increasing number of HMOs use primary physicians as a “gatekeeper.” The primary doctor is “capitated;” that is, paid a set amount per member per month, whether or not the member is sick. It is up to the “gatekeeper” to make referrals to specialists and, sometimes, to pay their fees and hospitalization costs out of the “capitation” he’s been receiving.

At its best, the “gatekeeper” approach can provide more focused care and eliminate needless visits to expensive specialists. On the other hand, the “gatekeeper” approach also contains an incentive to under-serve patients and possibly delay getting more advance care, an AMA report concluded. Real evidence either way “is either inconclusive or lacking,” the report said.

The AMA isn’t the only one having a tough time judging quality. Neither the government nor trade groups nor consultants have yet agreed on a way to measure quality in health care, whether with prepaid plans or conventional fee-for-service physicians. In the meantime, the consumer is left to judge the new, “efficient” medicine the same inefficient way he judged the old-through word of mouth, personal impressions and asking lots of questions.

“The average poor working stiff is not sophisticated (enough) to know what he’s getting,” contends Joe Rivard, a St. Paul malpractice attorney who represented the Bohnen family in its lawsuit.

“All he knows is he’s promised he and his family will be taken care of as part of an employee benefit. That’s great.”

©1986 Michael Millenson

Michael Millenson, a reporter on leave from the Chicago Tribune, is chronicling the deregulation of the American health-care system.