There were about 125 students in the Gadsden, Alabama High School senior class of 1930. The editor of the yearbook had the bright idea of using three adjectives to describe each member of the class. Under the name of Hazel Brannon, it read: “Industrious, Independent, Indomitable.”

I’ve learned since that those three qualities are not only valuable for a newspaper editor and publisher, but absolutely necessary if one is to survive and succeed.

It’s too bad the members of the White Citizens’ Councils who wanted me dead, or at least out of Mississippi, many years later did not know about those three “I” descriptions of me as a high school senior. It would have saved all of us a lot of trouble and heartbreak.

At the age of 18–after having worked for a weekly newspaper for nearly two years–I made up my mind what I wanted to do in life: edit and publish a weekly newspaper of my own. But I had to get my college degree from the University of Alabama first. Then I had to find a paper that I wanted in a nice community with prospects for growth and development in the future.

In 1935, a school friend of mine was practicing law in south Alabama and through a newspaper friend of his found out from the Publisher’s Auxiliary that a weekly in Durant, Mississippi was for sale. They went over to Durant to look at the property and find out the price. The next weekend my college boyfriend and I went over and inspected The Durant News and the town of Durant, just under 2,500 population.

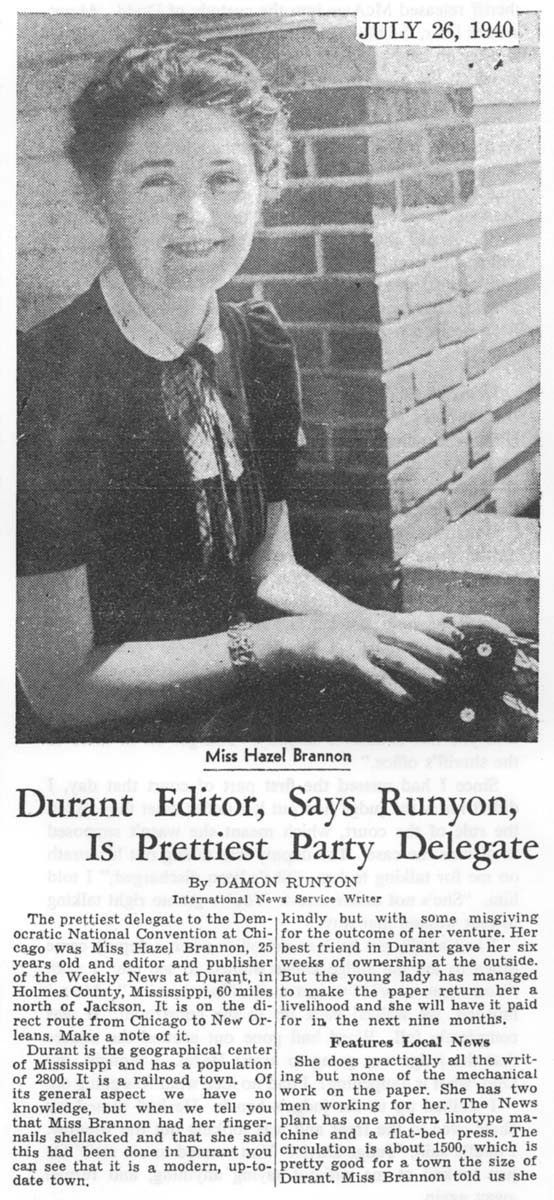

I was not impressed with the shop and equipment but I thought that I could manage it–if I could borrow the $3,000 down payment. Within a week or so the deal was completed. At age 21, I became the owner, publisher and editor of The Durant News. Seven years later, I bought the larger weekly paper in Holmes County, The Lexington Advertiser, again with borrowed money-and paid it off ahead of schedule. As the owner of the only two newspapers in a county without radio stations, I became the voice of Holmes County. I didn’t consider myself all that important, but I considered it my responsibility to do what I could to promote a county in which everybody could live in peace and without fear.

Durant was and is a friendly town where people don’t put on airs. Their minds are always open to new ideas, especially if it’s anything to boost the city and its citizens. When I arrived there in the mid-1930s, Durant was a railroad town. The only industry was a sawmill. Durant sits on the main line of the Illinois Central Railroad (which runs from Chicago to New Orleans) and most of the town’s families had someone working on the railroad.

My staff consisted of a linotype operator, two printers and a high school girl who worked afternoons. I got the news and wrote it, and solicited advertisements. There is always something to cover for a weekly newspaper–seven days and seven nights a week.

Law enforcement in the city and county was honest and good. Liquor and beer were illegal statewide. Sheriff Walter L. Ellis did his job as well as could be expected, and Holmes County was a decent place to live and bring up a family.

But there was trouble brewing in paradise, that being the larger area outside the towns and cities. More and more people were getting into the bootlegging business, which came to be known as one of the most lucrative professions in the county. The bootlegger’s “joints” were off the main highways, back in the woods, but they’d have a good road going in so you could get in and out. Slot machines and crap tables were added so that people who came by the “honky tonk” would stay longer, drink more, and gamble until they ran out of money. Grocery money was being spent on gambling and some young couples were having a hard time feeding themselves and their babies.

There were only two or three places in the county that really went in for it big and put in crap tables. The main one was called The Rainbow Garden. It was a building that had been used for years as an enclosed skating rink. The Powell brothers, who owned it, fixed the place up like a nightclub, and they had a large space for dancing. They brought in name bands from Chicago, and in back they had a gambling room. Of course, all this was illegal.

Holmes County was on the verge of disaster and that was clearly understood by the time the 1944 election for county officials began. The office of sheriff was won by Walter J. Murtagh, well-known and respected in his own community of Pickens, where he had the Ford dealership. He was not personally known by the great majority of white people (the ones who did the voting) but his character was good and he was respected by the people of Pickens, who knew him best.

Bootleggers Take Over

Walter Murtagh himself had told me when he ran for sheriff that he was going to clean up Holmes County and make it a decent place for people to live again. He just told people what they wanted to hear. After Walter became sheriff, bootlegging proliferated. The bootleggers ran the county. They all had Cadillacs and I don’t think any of them had fewer than three cars. They spent more money than anyone else in Durant. And everyone knew about it, including the sheriff.

Arrests for drunk driving increased. One woman in Durant was backing out of her driveway in broad daylight and a drunk soldier hit her car, badly injuring her. (There was an Army camp north of the County and the soldiers came down to Durant on weekends to buy liquor and beer.) It eventually got so bad during Walter Murtagh’s regime that bootleggers were going out to the country and bringing back young girls to put in the back rooms of their honky tonks for entertainment. Some of these girls were only 14 or 15 years old.

It was one thing for them to go along quietly out in the woods off the main highway meeting what you might call a legitimate demand from people who wanted to drink. But then they moved out in the open, so that you’d have it thrown in your face every time you rode down any of the highways outside town.

A Lexington girl who was married to a Durant boy called me and asked if she could talk to me about something serious. She told me they were going to have to leave Durant. I said, “Why? Has he lost his job?” She said “No, but he might as well have. Every week his paycheck is gone by Monday morning. He goes out there to the Rainbow Garden and we don’t have grocery money the next week.” They finally moved to Jackson, where he got a job.

I began letting the people know that something was wrong. I wrote a warning in the newspaper. I said that I was adopting a policy effective the following week: If anyone was arrested and charged with a crime which involved drunkenness, or other serious offenses, I would print the name of the person arrested and what they were arrested for.

Then I went to see the sheriff. He was just as cordial and as nice to me as he could be. He called me Hazel and I called him Walter.

I said, “Have you got a few minutes that I can talk to you privately?”

He said, “Sure, of course I have, come on in.”

I said, “Walter, I have come on a mission that I don’t like, but one which I think is absolutely necessary. I don’t know whether you’re being paid off by the Holmes County bootleggers or not. But you have sworn an oath to be the protection of this county and you are not doing that. Whether you are being paid off, that’s between you and them. But, my God, man, if you are not being paid off, won’t you please do something to stop this thing?”

He had a kind of sad face–and not too bad looking–but his eyes went way back in his head and he looked a little strange compared to some people. And he just looked at me and shook his head, as if to say “How sorry I am.”

I said, “I have responsibilities, Walter. I’m not Jesus Christ, and I won’t propose to dictate the morals of the people of Holmes County, but I do think I have the responsibility to keep them informed about what’s going on in this county. If you don’t do something, I’m going to have to open the window and tell them what’s going on.”

Walter just shook his head sadly. He didn’t say “yeah” and he didn’t say “nay”. He didn’t dispute anything I said, but he didn’t say he was going to make any changes.

I had been running the arrest notices for some time to educate the people to what was going on. The vast majority did not know, because the vast majority did not go out honky tonking at night. The men worked in their overalls out in the fields plowing the land–most of them didn’t even have tractors. Every penny they made was hard to come by. They had a difficult time getting a dollar together to give their kids to go out on dates. And then the kids would come into town and see these people driving around in their Cadillacs, all dressed up in a suit and tie, even in the middle of summer. It was setting a bad example for the kids and giving them a false sense of values.

That’s when I made what I called my “declaration of war.” In the newspaper, I called on the sheriff to enforce the law. When he still didn’t take any action, I wrote in my column Through Hazel Eyes, which ran on the left side of the front page, that I had talked to the sheriff and offered him space in the newspaper to make any kind of statement he’d like to make about his plans for the rest of his term.

“This is what he said,” I wrote. Then I left the rest of the column blank.

Meanwhile, up near West, a little country town about nine miles north of Durant, a white farmer named J.F. Dodd had a saddle stolen from his place. Dodd was good, solid church-going people, but he accused a black man of the theft. Leon McAtee was a slightly built, 35-year-old black man who lived on the Dodd place all his life. McAtee was arrested, but he was only in jail for three days when Dodd told the sheriff he wanted to drop the charges. The sheriff released McAtee into the custody of Dodd. About a week later, the black man’s badly beaten body was found in a bayou over in Sunflower County (this was the county in which the first White Citizens’ Councils were later organized in Mississippi).

To his credit, Sheriff Murtagh made a complete investigation of the case which resulted in six white men being jailed, including Dodd. Five were charged with manslaughter in what came to be known as the Leon McAtee flogging case. Two of the defendants admitted to the sheriff that they had whipped McAtee, but they claimed they did not kill him. All were acquitted due to lack of evidence.

Much later, it was discovered that two children who lived on Dodd’s place had taken the saddle.

Separate Seating

I carried the complete proceedings of the trial in The Durant News & Lexington Advertiser. The courtroom of Holmes County Circuit Judge S. F. Davis was packed each day. In those days, the whites and blacks didn’t sit together. The whites sat down on the main floor and the black people sat in the balcony.

When the black man’s widow, Henrietta McAtee, was on the stand one day her voice was so low I wasn’t sure what I caught in answer to a question. She was the last witness to testify that day, and after court had adjourned, I asked her to repeat her last statement for me. She was standing by herself at the bottom of the stairs and I couldn’t have talked to her for more than two minutes. Suddenly, one of the sheriff’s deputies came up to her and in the most vicious manner he said, “Henrietta, the judge told you not to talk to nobody. You get on in there to the sheriff’s office.”

Since I had missed the first part of court that day, I didn’t know the judge had put her under what they called the rule of the court, which meant she wasn’t supposed to discuss the case. The deputy was taking out his wrath on me for talking to her. “She’s been discharged,” I told him. “She’s not under arrest. You’ve got no right talking to that woman that way.”

I had hardly got back to my office when a deputy came down to tell me Judge Davis wanted to see me. I said, “You mean now? I’ve got a deadline to meet.” After I finished, we walked back up to the courtroom. It was completely full. Word had gone out around the square that the judge was going to arrest Hazel. I thought, my God, what is happening? I had no idea what was going on.

I walked up to the judge’s bench. He had turned his chair over to the right and was looking out the window. I finally said, “Judge Davis? You wanted to see me?” He just looked at me without saying anything, and turned away again.

I rapped my knuckles on the bench and said, “Judge Davis, what did you want to see me about?”

He said, “Young lady, you be in this courtroom at 9 o’clock tomorrow morning and you’ll find out. And bring your attorney.”

I said, “Have I committed a crime?”

He said, “Do you deny that you questioned Henrietta McAtee?”

I said, “I don’t deny that I talked to her.”

He said, “She was under the rule of the court and you are being cited for contempt.”

I said, “Contempt of your court?”

Then I apologized and told him that if I had committed a crime, it had been out of ignorance. But the next day he charged me with contempt, and fined me $50 and sentenced me to 15 days in jail. The sentence was suspended for two years pending good behavior so that, as the judge put it, “if you run in with this court again we won’t have to try you next time. We’ll just throw you in jail.”

The judge didn’t stop there. In open court, he chided me for carrying out a “great campaign” to clean up the bootlegging and gambling in Holmes County. He said: “If you read history, you will see that the only perfect being didn’t make much of a hit with His reforms. He reformed a few and left this advice: Before you clean up someone else, clean up yourself.”

Then the judge added: “So few of us pure are left.”

The people in the courtroom gasped.

Punished For Crusade

The judge clearly showed that he was punishing me not for contempt of court, but for my three-year crusade against the lawlessness of the local power structure.

An editorial in the Jackson Daily News the next day chastised the judge for going out of his way to slap me on the wrist. The editorial called me a “brave, lionhearted woman” who had been waging a “gallant battle” against the “reign of lawlessness” in a county where “she gets no aid or encouragement” from law enforcement officials.

I appealed the sentence to the Mississippi Supreme Court, which subsequently dismissed it. In my column on October 24, 1946, I wrote:

“Wouldn’t we see a great improvement in general conditions, if all the laws of Holmes County were given the same attention by the sheriff’s office that the rules of Judge Davis receive?

“Perhaps this case will result in more serious consideration being held for the personal rights of all men, white or black. It is a situation demanding deliberate consideration from thinking men and women everywhere.”

We elected a sheriff in 1948 who said he was going to clean up Holmes County, and did. The bootleggers closed their places before he even got into office. Many of them left the state. I had beat them, but then the White Citizens’ Councils came in, and that was when they really went to work on me.

©1983 Hazel Brannon Smith

Hazel Brannon Smith, editor of the Lexington (Miss.) Advertiser & Durant News, is writing a case study of an American community newspaper under pressure.