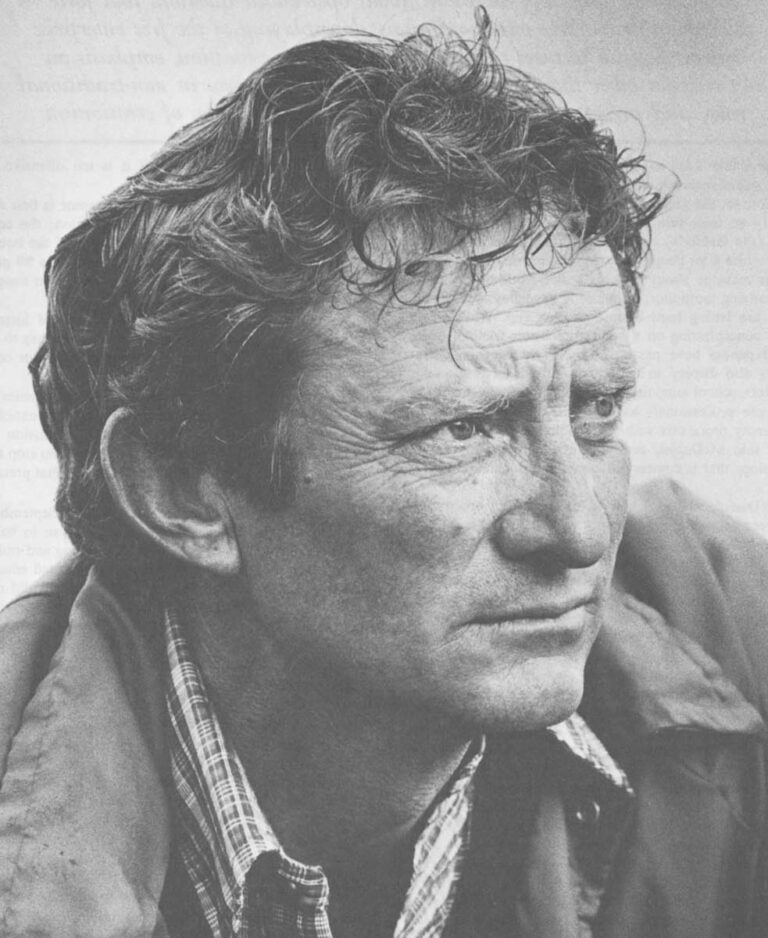

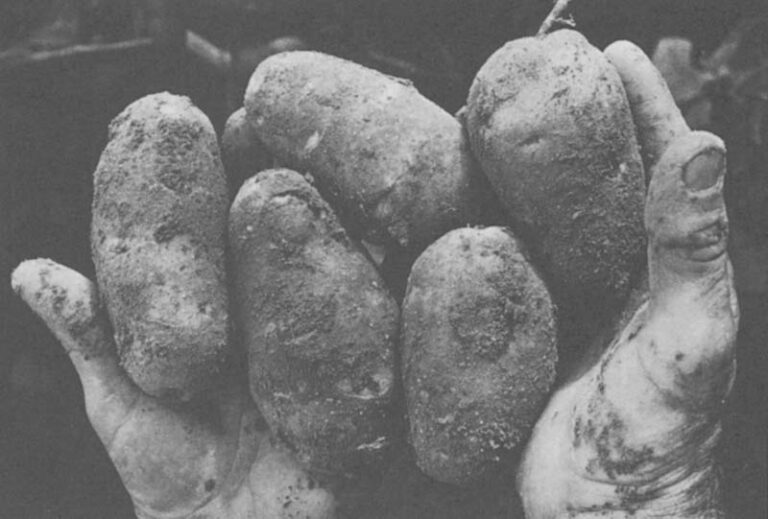

Lou Thiel, 46, a college graduate and second generation potato farmer from Idaho Falls, Idaho, believes that “farming is a poor business but a great way of life.” Thiel is worried about skyrocketing costs–a piece of equipment bought for $2,600 eight years ago cost $13,200 to replace this year. Thiel attributes his success to market skills, special irrigation techniques, and knowing how to raise a quality crop.

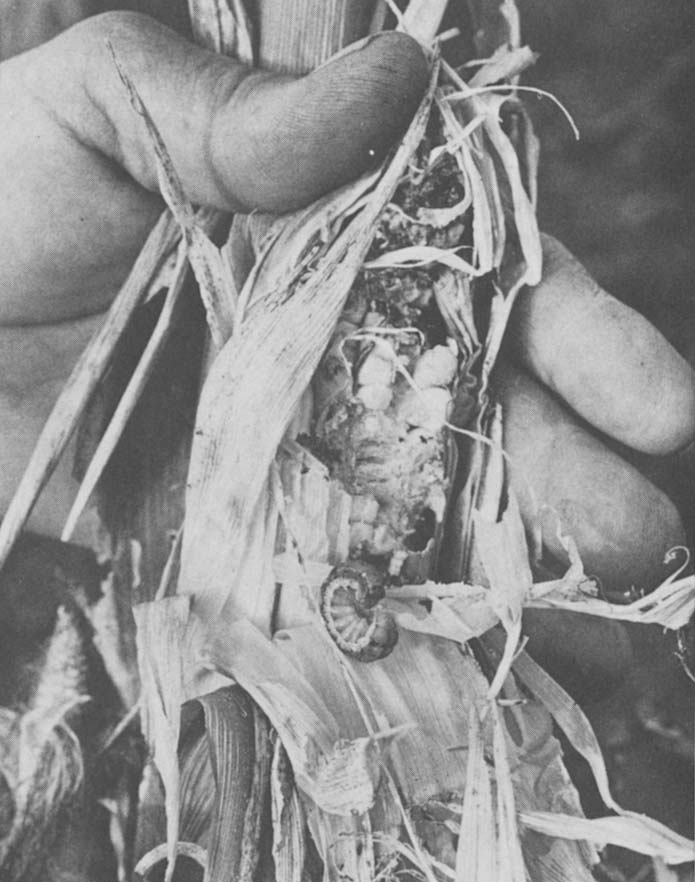

Many farmers say the drought in the Summer of 1983 was the worst in 50 years. Wilbur Burton (upper left and right), a Virginia farmer with 850 acres, lost 80 percent of his corn crop. Agricultural officials predicted drought-related losses of $200 million for Virginia farmers alone. Across the nation, food prices are predicted to rise as the drought takes its toll.

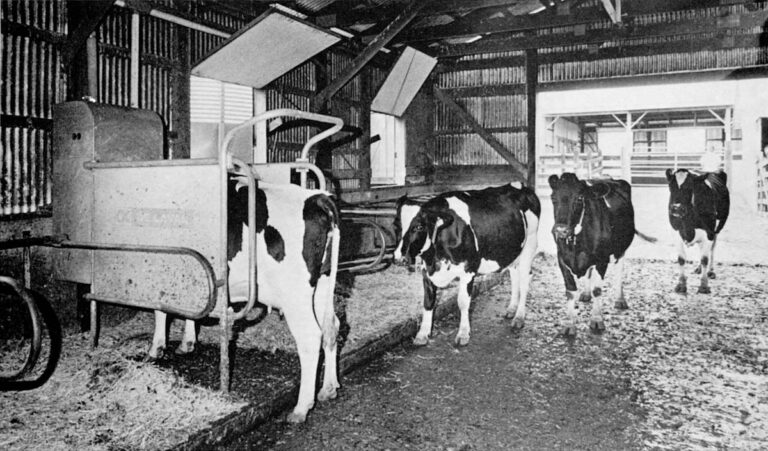

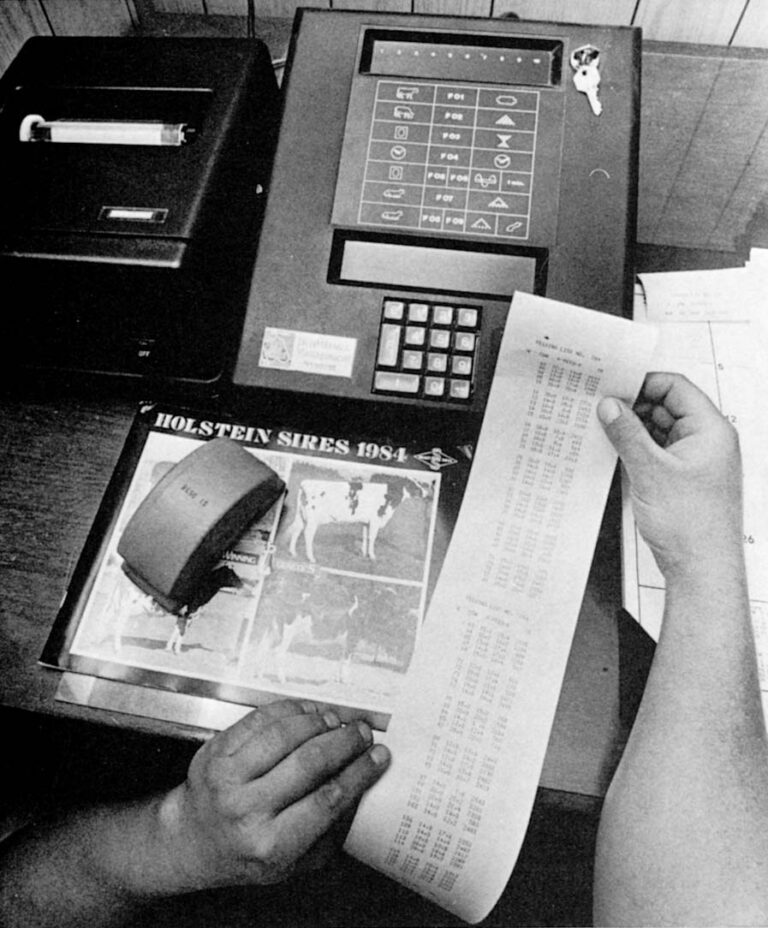

Farms are becoming more mechanized. Dairy farmers use computers to monitor the amount of food consumed by their cows. The cows line up to eat in a particular stall. They wear special collars which use sensors to record how much food each animal has eaten. The sensors relay the data to a computer in the main barn.

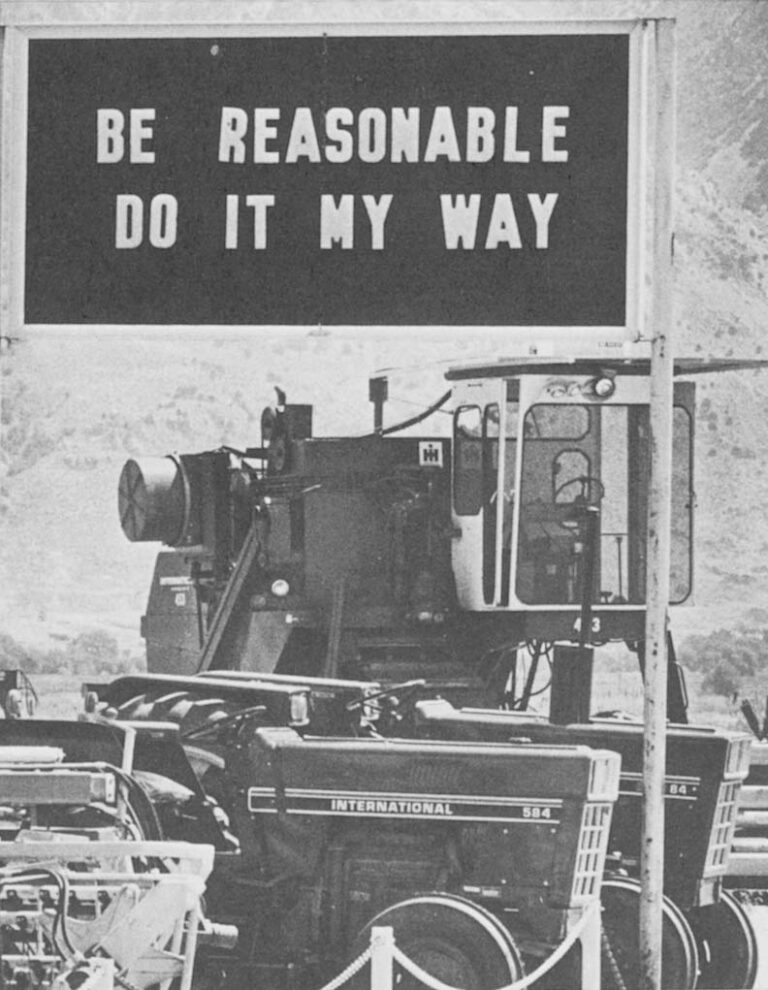

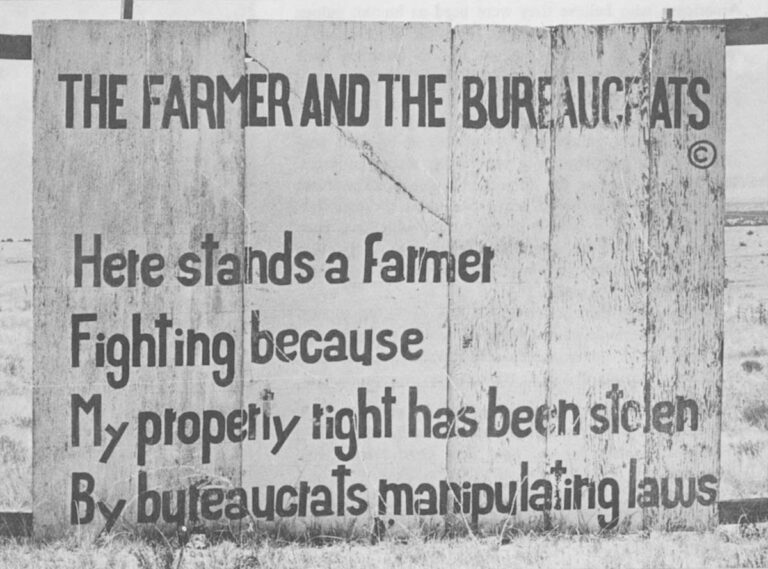

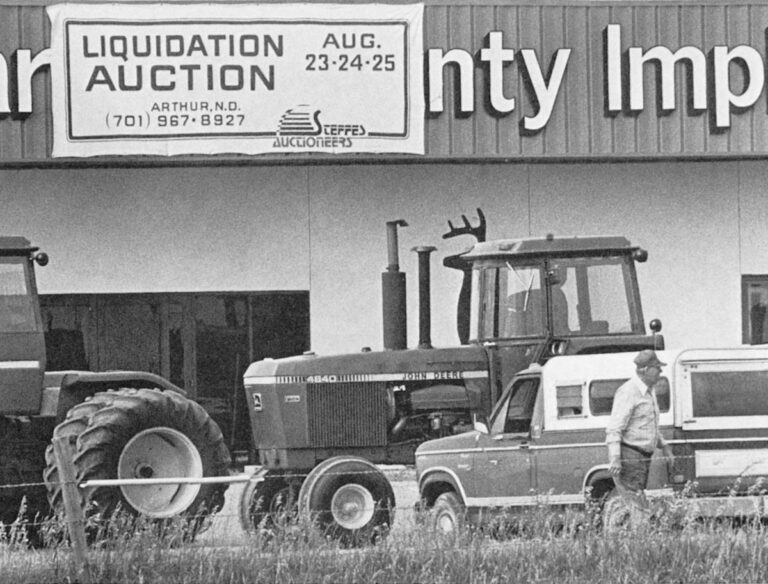

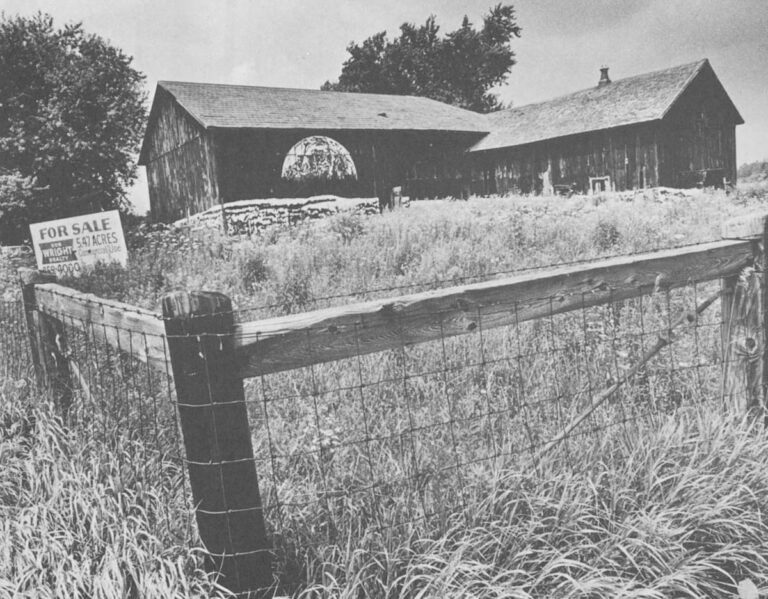

Protest signs on a Colorado highway and “Farm for Sale” signs across the nation speak of farmers who are disillusioned with government regulations, or who have decided to leave the business.

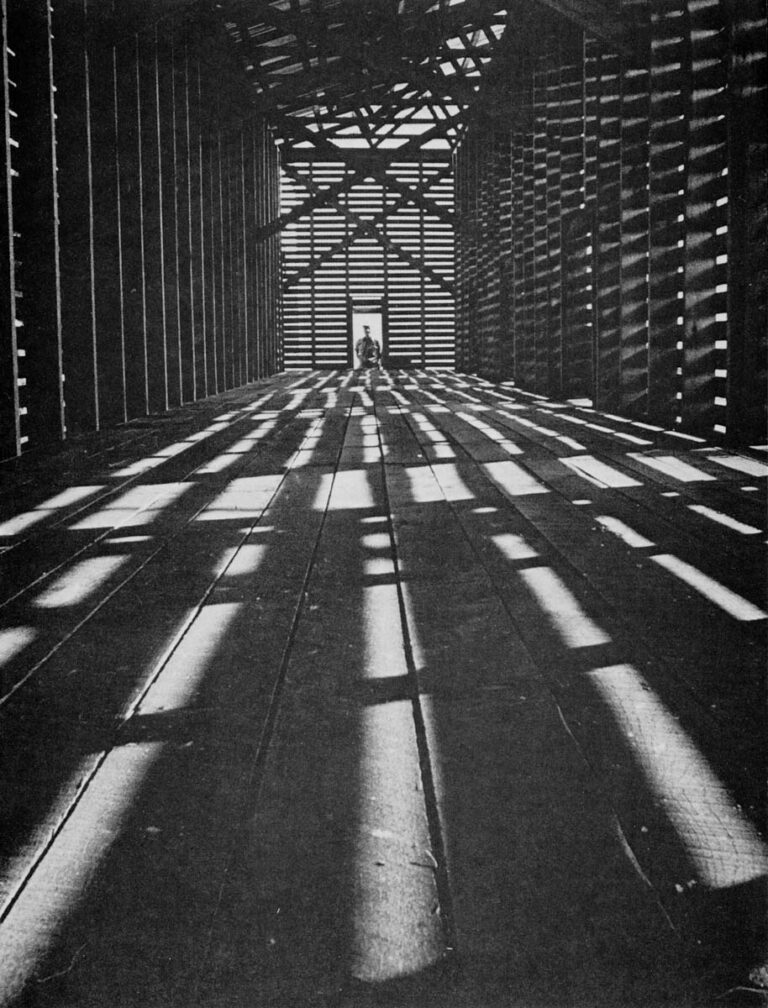

More farmers are becoming big businessmen. They are college graduates who have learned to use the latest technology to increase production. On the modern farm, computers run tractors as well as offices. Heavy production of basic commodities has pushed market prices down. Dairy farmers are being paid by the government to refrain from producing milk and, nationally, government warehouses are jammed with surplus dairy products. The government has sponsored land diversion programs to deal with the problems of excess grain. The big farmer may survive, but escalating costs, weather losses and other problems are chasing away the young farmer.