MANAGUA–Nicaragua’s Foreign Ministry is housed in an expropriated neighborhood complex of former stores and boutiques. Its staff can often be found searching dog-eared book indexes to document upcoming diplomatic speeches. Computerized U.S. libraries could locate this information in minutes, but here it takes days–if indeed it can be found at all. Before fleeing the capital, President Anastacio Somoza’s troops destroyed books and vandalized state libraries. Shelves remain unstocked today even at the universities.

Like any new kid on the block, post-revolutionary Nicaragua must find ways to negotiate with world powers while retaining its base of support at home. On the international playing field, communications is the first line of defense. Modern diplomacy is increasingly a matter of how skillfully a nation can communicate, but the Third World argues that it is unable to speak for itself and–like minority communities in the U.S.–loses by default.

As contestants, Nicaragua and the U.S. are ill-matched–a flea against an elephant. The U.S. is a postindustrial giant which emphasizes personal computer purchases as a desirable middle class goal. It gathers and dispenses information with the most sophisticated technology on earth, relaying transmissions by satellite to more than 135 million television receivers and 1,763 daily newspapers. These are read by 63 million subscribers, who are also supported by an extensive telephone and postal service. There are 74 telephones for every 100 people in the U.S. The Post Office offers overnight mail delivery.

“Today,” says journalist and media historian David Armstrong, “half of the U.S. gross national product is generated by the production, dissemination and consumption of information in its various forms: the press, books, movies, records and tapes, government and corporate documents, legal briefs, computer printouts, radio, video discs and tapes, broadcast and cable television.”

A time warp south of this world communications empire lies Nicaragua, a peasant society with little technology, where the corn god coexists with Henry Ford. There are less than 1,700 miles of paved roads, only six television stations, three daily newspapers and a few limited computers. People regularly send family messages via radio programs: “For the Jesus Montecino family, your niece and her children have arrived safely at your aunt’s in Masaya.” Managua residents often cluster near airport exit stations hoping to get international travelers to mail their letters out of the country in order to speed delivery.

Dwarfed by the U.S. (Nicaragua is slightly less populated than the city of Los Angeles), Nicaragua enters 1983 with grave problems, not the least of which is that it has alienated North America. The richest power in the world seeks to destabilize the country whose gross domestic product is little more than half the $3.2 billion annual sales of an American firm like Warner Communications.

Feeling isolated and besieged by what the Reagan Administration admits are hostile CIA covert activities, Nicaragua has reacted by cracking down on internal dissent. Individual freedoms have been limited “in the interest of national security.” There are obvious cases of Sandinista overreaction: scores of Miskito Indian leaders were jailed last year without formal charges; sweeping press censorship was initiated; and charges continue to fly between the Sandinista government and its critics over economic policies, civil rights and aid to Salvadoran rebels.

Nicaragua’s revolutionary leaders must also shore up support at home by satisfying the country’s 2.6 million people, long divided and ignored by former politicians. The country must also present a united national front in the face of U.S. harassment, which now threatens to propel Central America into regional hostilities.

Like all governments, the Sandinistas try to motivate citizens toward national goals by strumming cultural chords. Nicaragua is struggling to recover from the triple effects of the devastating revolution that toppled the 45year Somoza dictatorship in 1979, destructive floods last May, and a recent drought.

Ninety-five percent of the population is Roman Catholic; three-fourths are mestizo, a mixture of Indian and European. Most of the nation lives within pre-industrial time, its daily rhythms tied to nature. The extended family, love, enduring friendship and sharing are important. Like most Latins, Nicaraguans are ready to party on short notice. Death is accepted as an inevitable part of life’s scheme.

Today, Americans are long conditioned to time restrictions imposed by industrialism. Members of international delegations traveling in rural Nicaragua invariably set their digital wristwatch alarms according to distant office schedules while their hosts in any number of small local towns are awakened daily by roving livestock banging against houses at dawn.

By redesigning the economy to combine capitalism and socialism, the post revolutionary government seeks to prevent the kind of system that allowed Somoza to thwart the growth of the nation’s business sector while he exploited Nicaragua like a fiefdom to acquire immense personal wealth. The new government also means to narrow the class gap but so far, about 70 percent of the gross domestic product remains in the private sector. Elections are scheduled for 1985.

For U.S. supply-siders, such economic plans are heresy. But Nicaragua, like most of Latin America, bewilders many other Americans. U.S. religious and civic institutions, after all, developed without repeated civil wars. English Protestants who founded the country brought religious beliefs that evolved into secular theories of common equality. U.S. capitalism is anchored in the Puritan work ethic.

Hispanic America’s Past

Hispanic America’s very different past still controls its present. Catholic Spaniards ruled by royalty settled Latin America–trapping it between two rigid hierarchies: the church and the monarchy. It cast off the monarchy during the 19th century wars of independence, but the break was incomplete.

Control of national wealth transferred from European elites to their Latin American descendants, while a powerful church continued to reinforce rule by elites. For centuries, religion was the only authority for illiterate populations and it told them to respect the status quo. A loyal, usually brutal, military protected corrupt dictatorships. Not until liberation theology put the church on the side of the oppressed was religion used to back popular demands for social change.

Thus, winning Latin American independence is a two-stage effort: First came the armed struggle against Spanish rule, followed more recently by social movements trying to pry power and economic control away from national elites who continued the colonial system. Since Mexico’s 1910 Revolution, this effort has characterized Latin America’s major political conflicts. Countries like Cuba, Guatemala and Chile attempted completion of the cycle, but opposed by U.S. policy, democratic ideals were distorted or done away with completely. The same ominous tensions are emerging in Nicaragua.

In Central America, as in other Latin American countries, U.S. foreign policy makers too easily discount the strength of popular nationalism. Even Nicaraguan opposition leaders contend that the U.S. wrongly expects dissatisfaction with the new revolutionary government to lead Nicaraguans to seek help from the U.S.–the government that trained the hated national guard and kept Somoza in power.

But nationalism flourishes, inspiring political rallies, speeches and a cultural renaissance. Both Carlos Tunnerman, minister of education, and poet-priest Ernesto Cardenal, minister of culture, relied on these feelings to bond citizens together when they laid early plans to improve Nicaragua’s ability to talk to itself.

The literacy campaign which, according to government figures, lowered illiteracy from 51 to 12 percent, stressed themes of patriotism. Its young teachers, supplied with tape recorders, also captured much of the nation’s oral tradition, which is to be printed, illustrated and distributed by the Ministry of Culture. At the end of the campaign, several hundred thousand pupils received a small transistor radio to link the widely scattered populace to centralized broadcasting.

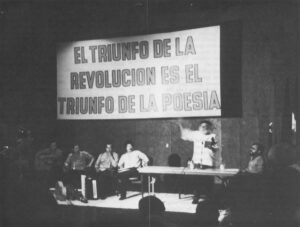

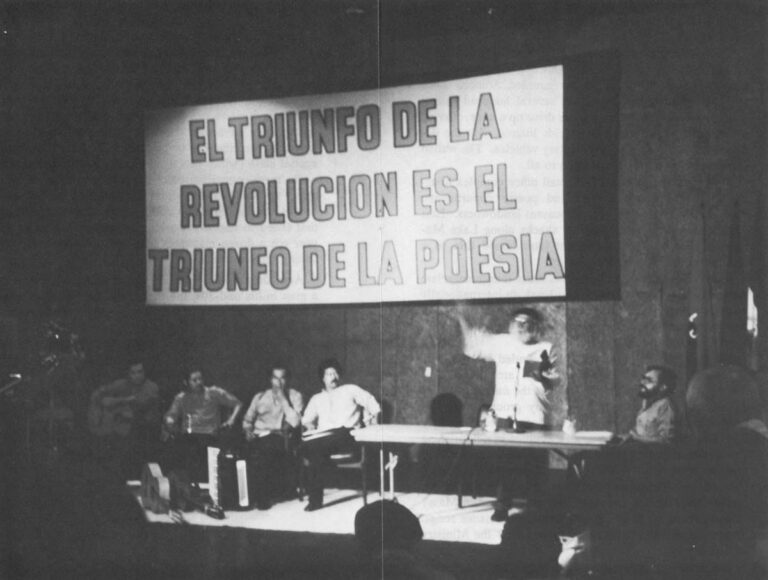

Culture minister Cardenal tapped tradition. Creating poetry, for example, is a national pastime predating revolutionary fervor. Nicaragua’s best known poet and the first Latin American writer to influence European authors–Ruben Dario, who died in 1916–is a national hero. The Ministry of Culture enhances these creative tendencies with both direct and subliminal messages. It sponsors a number of arts programs, and the location of the ministry itself affords a symbolic stage.

The ministry is at El Retiro (The Retreat), which lies on the outskirts of Managua, sprawling across a hilltop vantage point where a heavily guarded Somoza once strolled, scanning his domain of several hundred rolling acres. To reach El Retiro, visitors drive up a wide, curving private road-past overgrown fields littered with the defeated national guard’s rusty military vehicles. The walled private entrance now stands open to all.

Beyond the main house is a small office complex housing music, literature, theater and poetry departments, bordered by a ragged village of peasant landowners. Last May, floods destroyed squatters’ shacks along Lake Managua’s shores. The government later issued title to a small piece of land for each family.

But the Ministry of Culture does more than manipulate symbols. At its head, Ernesto Cardenal, an internationally respected poet whose work was banned under a Somoza decree, encourages the national passion for poetry with special ministry programs.

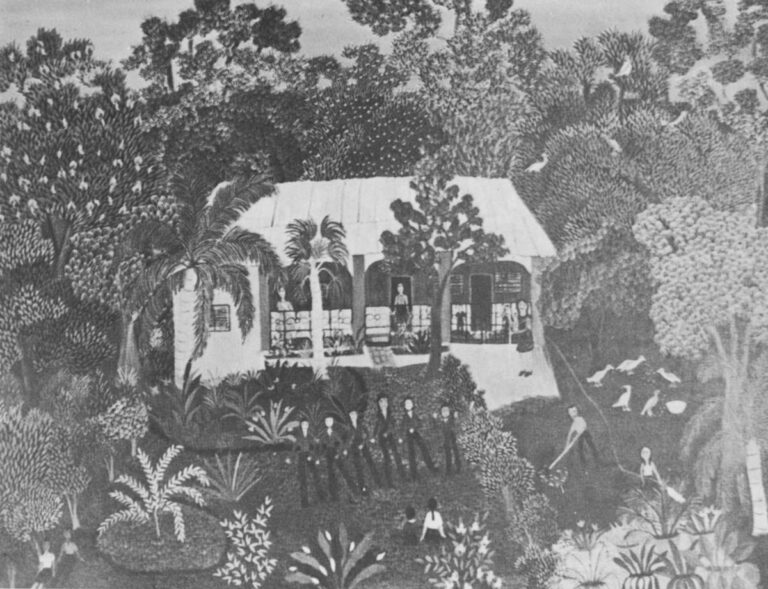

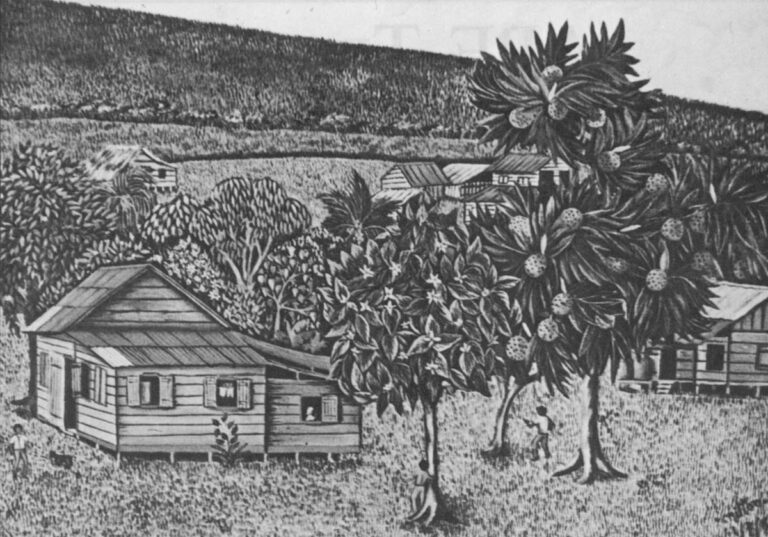

During the mid-1960s, Cardenal founded Solentiname, a peasant village on Lake Nicaragua’s archipelago. Its 30 original couples established one of the nation’s earliest comunidades de base–a Bible study group seeking to understand and apply liberation theology concepts to daily life. The village, based on mutual support in a flourishing arts setting of poetry, music, folk and primitive art, quickly grew to more than 1,000 people. Carlos Mejia Godoy, now one of Nicaragua’s foremost musicians, began his career there, scoring the misa campesina (peasant Mass) before moving on to composing popular resistance songs. Today, these same trends are sponsored by the Ministry of Culture.

The first organized attack against the Somoza regime by Sandinista forces struck from Solentiname on October 12, 1977. National guardsmen retaliated by leveling the community, forcing its poetry and music onto underground radio waves.

In a country known for its love of song, the folk singer is culturally familiar. During the revolution, a number of ballads were written for a new didactic purpose. “El Garand,” for instance, which was originally sung over Radio Sandino (the clandestine rebel station) is both a catchy tune and a musical lesson on how to disassemble, load and fire the M-1 rifle. Since half the nation was illiterate, the song’s teaching importance is obvious.

Contemporary songs and poetry focus on themes of fraternity, combat, and memories of fallen comrades. Dario’s 1904 poem, “To Roosevelt,” condemning U.S. aggression is widely quoted; his work also regularly appears in the weekly cultural sections of all three daily Nicaraguan newspapers.

Newspapers provide an important forum for Nicaragua’s poets. Occasionally, they display work by leading political figures, including Serge Ramirez, member of the ruling three-man junta, and Togas Borge, one of nine directorate officials.

Poetry workshops are sponsored by the Ministry of Culture in military barracks, militia headquarters, union halls, work sites–anywhere there is interest. Trained writers give free instruction.

“Poetry is the first art of literacy,” says Julio Valle Castillo, Cardenal’s assistant. “Right now, ours still celebrates the triumph after years of writing in the dark, clandestinely. Nicaragua has many anonymous writers–a necessary safety factor under Somoza when only dead poets signed their work. Nicaraguan poetry is an anthology of resistance.”

Political oppression means cultural repression as well, says Ernesto Cardenal. “Today, the arts belong to the community because the people produce the arts. Neither artists nor audience is marginalized.”

It is not unusual for art to use nationalism to show that social change is authentic, that a revolution is nationalistic, according to David Kunzle, author and UCLA art history professor, who specializes in Latin American popular culture. “’Art draws from historic roots,” he says. “Nicaragua’s corn festival in 1981, for example, used pre-Columbian figures to remind people that maize is a native grain given by the ancient Amerindian to the West. Corn has become a national symbol of economic and cultural independence, because at the moment when wheat supplies were cut off by the United States, it made good sense to eat corn instead. Mounting maize festivals and promoting the use of the grain on food and drink allows the Nicaraguan Ministry of Culture to emphasize its own national tradition.

“Primitive art in Nicaragua today,” he adds, “is also truly in the new Nicaraguan style. It records everyday village life events, and tells of suffering in the revolution.”

Nicaraguan song and art has had little impact among Anglos, though they sometimes strike themes familiar to U.S. Latinos, who also use the pre-Colombian past to anchor their culture in history. Most U.S. Latinos, however, live in enclaves segregated by ethnicity, class and geography. Their theater, arts and music appear mostly in the barrios (Latino neighborhoods). Few Anglos venture there for middle-class recreation. Like Third World countries, these minorities talk only among themselves. Cultural exchange is limited to one-way expression; media, which could become a vehicle of cross cultural communication, is virtually closed to minority access.

Global communications conglomerates, many of them based only minutes from large Latino neighborhoods in Los Angeles–where more Mexicans live than in any other city in the world except Mexico City–show very little evidence on their pages or TV screens of the large local Latino population.

Media Ignores Latinos

Latino participation in the communications industry is minuscule. Although almost 900,000 Latinos (not counting the estimated hundreds of thousands of undocumented Latinos from Mexico and Central America) live in the immediate area it services, fewer than two dozen Chicanos work on the Los Angeles Times’ editorial staff of about 700, none in policymaking positions. Television shows and commercials usually lack any hint of Latino participation in U.S. society.

Last October, after blasting the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times and the television industry for their failure to cover the Latino community or to address their concerns, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) filed a class action discrimination suit against major television networks, production studios and advertising agencies.

LULAC president Tony Bonilla says that lack of Latino news coverage and failure by media to portray them in a positive way distorts reality. “It is important that this situation be corrected,” he argues, “that Latinos gain access to communications. Mass media, especially television, is the most powerful form of education. The larger community, both policy makers and ordinary citizens, need to know more about us. Considering our immense growth, they should know who we are, what we value, what we do, what we contribute, how we spend. Media access–fair coverage–makes us stronger as a community, both politically and economically.”

David Kunzle believes that “Latinos are perceived mostly through negative stereotypes, whether it be a small Latin American country or a U.S. Latino community. Stereotypes are a most effective means of channeling consciousness.”

Rene Anselmo, founder and president of the Spanish International Network (SIN), who vainly spent several years trying to interest American networks in Spanish-language programming before establishing his own specialty network (which now shows programs on 200 affiliated stations) moves quickly to the heart of the issue: “If you don’t exist in media…you just don’t exist.”

©1983 Mercedes de Uriarte

Mercedes de Uriarte, assistant editor of the Opinion Section on leave from the Los Angeles Times, is studying social change in the U.S. and Central America.