MOCORON, Honduras–Here on the soft savannah plains and in the lush tropical forests, a story as old as the Spanish Conquest and as familiar as the United States role in the overthrow of the Guatemalan government and the abortive Bay of Pigs invasion unfolds.

MOCORON, Honduras–Here on the soft savannah plains and in the lush tropical forests, a story as old as the Spanish Conquest and as familiar as the United States role in the overthrow of the Guatemalan government and the abortive Bay of Pigs invasion unfolds.

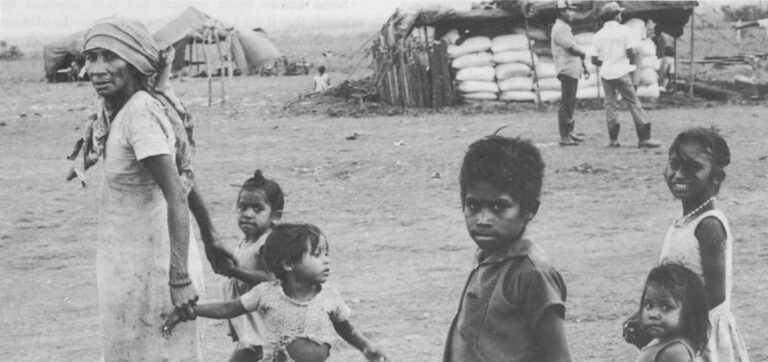

Miskito Indians, a small, indigenous group comprising less than 5 percent of Nicaragua’s population (less than 1/2 percent of Honduras), are trying to cling to a traditional way of life, even though they are now caught in the gunsights of political upheaval–pawns in an international conflict in which the U.S. plays an active role.

U.S. involvement in the internal affairs of Latin American countries evokes a certain deja vu for Latinos in the U.S. It also highlights an uneasy schism within the U.S. between exiled upper middle class Latinos who are allied with fallen right-wing governments, and other U.S. Hispanics who sympathize with Latin Americans whom they believe are struggling legitimately against oppressive regimes.

Some Cuban exiles in Miami who trained for the 1960 Bay of Pigs invasion are now helping train supporters of slain Nicaraguan president Anastasio Somoza for future action in Central America. Other Latinos, like Rep. Robert Garcia (D-N.Y.), oppose U.S. foreign policy and arms building in Central America.

The Miskito Indians were swept into this political drama in 1981 when they were forced to evacuate their riverbank settlements because of border tensions between Nicaragua and Honduras. Until then, the Miskito had retained their political autonomy, even after their lands were absorbed into the fledgling nations of Nicaragua and Honduras in 1860. This original agreement guaranteed their right to a separate culture, exempt from taxation and military service.

The Indians were largely concentrated on the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua in a 56,000-square-mile area once known as Mosquitia. There were also scattered pockets of Miskito living in an adjacent area of Honduras.

Subject to state law in theory, but ignored by Central American governments in practice, the Miskito remained disinterested in larger political issues, particularly those on a national or international level. Isolated by rugged mountains from the rest of Honduras and Nicaragua, the Miskito lacked roads, electricity, telephones and media to link them to the outside world.

Little changed in their river-dominated lifestyle. Even a United Nations World Court decision in 1960 which designated their own Rio Coco River as an international boundary between Honduras and Nicaragua had little impact, although it made many Miskitos Nicaraguan citizens. They continued to live on one side and farm or hunt on the opposite bank at will, depending heavily on rivers for food, transportation, recreation, drinking and washing.

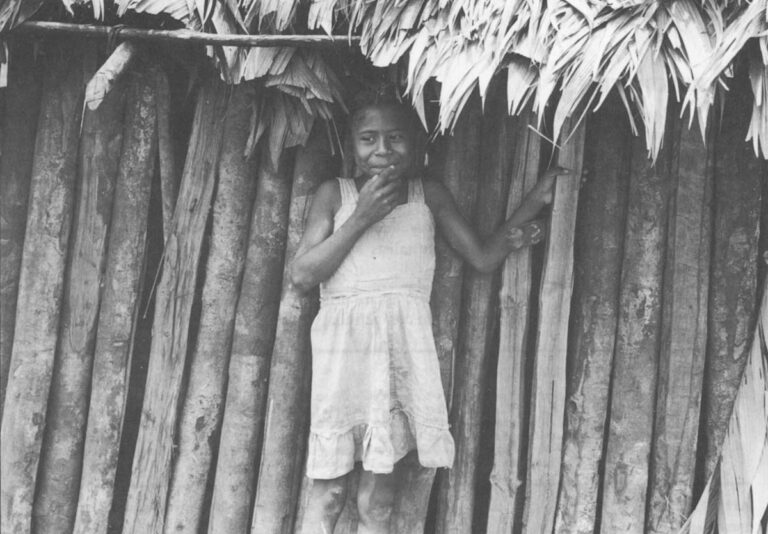

Usually 40 to 200 Miskito clustered in small riverside villages marked by wood-and-thatch houses on stilts to avoid flooding. Most Miskito are faithful Moravians, whose missionaries were originally sent by a Prussian count who became fascinated with the area in the 1800s. They are linked to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where the Moravian Church headquarters oversees its Western flock. Miskito culture values strong family ties, communal sharing, privacy, and abstinence from alcohol. Although the native tongue is Miskito, many also speak Spanish or English.

Political Pawns

Scattered across sparsely-populated lands, linked only by dugout canoes, Miskito life moved at a languid tropical pace until 1981, when they became pawns in a struggle between remote governments acting in self-interest. Conflict began in 1979 when Sandinista guerrilla forces toppled the 45-year-old Somoza dictatorship. Many of the regime’s former supporters and military forces fled into Honduras, where they mounted harassment strikes across the border against the Sandinistas, which also involved attacks on literacy campaign workers, peasants and Indians.

Miskito dissatisfaction with Sandinista projects in Nicaragua surfaced. Trouble between Sandinistas and Miskitos at a gold mine led to violence. Border raids grew worse. Eventually more than 100 Miskitos were arrested by Nicaraguan authorities; many of them still await trial.

By December, 1981, the Nicaraguan government decided that Miskitos. living along the Rio Coco could not be kept safe or completely free of guerrilla involvement. Invoking legal powers granted under a state of emergency, they rounded up residents of more than 38 river villages, moving them to settlement sites further inland. According to Nicaraguan figures, 8,300 Miskitos made the trip, accompanied by Sandinista soldiers. Villages, livestock, and personal belongings were destroyed behind them to prevent use by counter-revolutionaries. During and after the exodus, thousands of Miskitos fled into Honduras, where almost 10,000 now are housed in the United Nations refugee camp at Mocoron.

In Nicaragua, rural planners were engaged to design five model resettlement sites. A team of experts including architects, agriculturists, engineers, planners, teachers and medics planned the new settlements. Housing was prefabricated for quick easy construction. Government services denied to Miskito residents of Nicaragua under Somoza were made available; clinics and schools were built and staffed.

Work began immediately on a road connecting the Miskito settlements to the capital city Managua and the Atlantic port city Puerto Cabezas. Installation of electric and phone lines began six months later.

But all was not well. Miskitos resented paternalism and longed to return to their homes. Even those from areas where border incursions were most intense and the reason for moving more clearly understood and supported, were homesick. Women were dismayed to find their families swathed in blue plastic huts–blue filament was used for walls in emergency housing which intensified the heat during the day and chilled residents at night. They were unhappy about the permanent houses designed without any input from Miskito women. Instead of providing a separate structure for cooking–a Miskito social custom forged in tropical pragmatism–the attractive wooden, wide-porched homes were built as one compact unit. Many women were depressed and older men expressed concern for their health because of low spirits. Others worried about their personal losses. “Perhaps for the young men it isn’t so bad,” said one Miskito in his 50s. “But what they burned was my work of a lifetime, my future security. I have not the time or energy to do it again.”

Last spring, Miskitos spoke openly to visiting journalists, voicing complaints discreetly, but without obvious signs of fear. Some men disliked the regimentation of time, objecting to the long hard days in the field to sow the first crops, though they admitted that the Sandinistas worked right along side at the same chores. But several complained that Miskitos participation was “the right to participate in work, not in decision-making.”

Many Miskitos felt confined not only by Sandinista policies limiting their exit from the settlements, but by the remoteness of the location. Others worried about family now in Honduras, although it did help morale that whole villages were kept intact with familiar neighbors and friends nearby.

Sandinista opponents used the relocation to whip up American public opinion against the revolutionary government, which was already under stiff economic pressure from the Reagan Administration. Perhaps the most vocal was Stedman Fagoth Muller, 30, now an exiled Miskito leader and former head of an Indian organization formed during Somoza’s regime. Fagoth, educated in Managua and, according to Nicaraguan officials, a former Somoza informant, is now believed to be the key link between counter-revolutionaries in Honduras, the Honduran army units in the refugee camp area, organizers within the Miskitos refugee community itself, and the CIA. Fagoth led the mass exodus from Nicaragua in 1981 and has begun to consolidate forces with anti-Sandinistas in Costa Rica.

Human Rights Violation

UN Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick called the Miskito relocation “more massive than any other human-rights violation that I am aware of in Central America today.” Elliot Abrahams, the State Department’s top human-rights official, said of the Sandinistas: “They are dictators and they are going to run a pretty brutal country.”

But investigating human-rights groups have since found no evidence of mass killings, though there has been criticism of some aspects of the move, including Sandinista failure to advise people in advance–a tactic Sandinistas claim would have jeopardized Miskito security.

Meanwhile, across the Honduran border in Mocoron, conditions are difficult. Almost 10,000 Miskitos defined as Nicaraguan refugees are crowded into slat-and-thatch huts sprawled across a muddy plain a short walking distance from the small traditional village of Mocoron on the banks of the Mocoron River.

Within the camps there are complaints that goods and food are distributed unfairly.

Refugees at Mocoron spoke quickly, glancing sharply around. Almost all conversations at the camp are interrupted by the arrival of some uninvited Miskito who simply stands and listens, thereby ending any discussion. Talking to people freely is virtually impossible. Stopping Miskitos by chance to ask how they come to be at Mocoron, or when they arrived or even how they are, generally elicits the same response: “Ask the comite.”

The “committee,” a tightly organized group of Miskitos who run the internal politics of the camp, were angry with the press this summer, demanding their credentials and complaining that journalists were not getting the right story out. They repeated stories of Sandinista mistreatment and cited the number of Miskito refugees as proof of Nicaragua’s intolerable conditions.

“I was surprised at the level of their political sophistication,” said one U.S. government observer. “The refugee group was well organized.” Fagoth is a frequent visitor to the area, according to some relief workers, although officials of the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) deny that he has been seen in the camp.

“Usually he stays in Puerto Lempira as the houseguest of Captain (Leonel) Lunque,” said one relief worker.

Lunque is a Honduran army officer responsible for security in Puerto Lempira, the main regional town east of the Mocoron refugee camp. The town receives growing U.S. attention now that Honduras receives the second largest share of U.S. military and economic assistance in Latin America.

It was also the site of the two-week U.S.-Honduran joint military maneuvers last summer. The U.S.S. Portland, a troop carrier, paid a three-day call there in August. An airstrip is now under construction not far from the port city. It will be able to handle most of the planes in the Honduran Air Force–the strongest in Central America.

Not everyone sees the U.S. as a ministering angel. Members of the frail elected Honduran government, the first in 18 years, fear that U.S. military aid is tipping the already skewed balance of power between military and civilians. “Worse, perhaps,” said one Honduran legislator, “we worry that the United States is pushing us into a war we can neither afford, nor win.”

The U.S. role in Central America is quickly becoming an important issue in Hispanic political circles. Tony Bonilla, president of the 100,000-member League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), says the organization supports the economic assistance outlined in President Reagan’s Caribbean Basin Initiative, but opposes military assistance.

“We believe Latinos have important insights to lend the administration regarding U.S. foreign policy,” he said. “LULAC is now closely monitoring the Honduras-Nicaragua border situation and the Miskito problems there.”

For some time the UNHCR has been trying to move the Miskito, refugees away from the border. Miskito leaders within the camp have resisted, but plans now call for dispersal of thousands of Miskitos throughout the region by January in an attempt to restore traditional village life.

Not everyone is unhappy about the refugee situation, however. An official of Mocoron village, for instance, seized the entrepreneurial opportunity. First he rented out his own home to Peace Corps volunteers and moved in with his mother-in-law. Then he arranged for his wife and her mother to cook for the relief team, for a time turning the family kitchen into a communal dining hall. On the side, he took orders for new homes some relief workers wanted to live in, organized construction teams and delegated work. A mini business boom came to Mocoron.

Still, the rhythm of life remains the same as it has for centuries. The river serves as a daily gathering place at sunset when the Miskito men return home from their fields, piloting small canoes filled with herbs, twigs for a new broom, or jungle fruit.

It is the river that resettled Miskitos in Nicaragua say they miss the most. “The Rio Coco was the life of our village,” said one Miskito woman. “It was a real river, not like the little streams around here,” she said as her gaze swept the raw settlement gashed out of tropical grasslands on a muddy hillside.

Resistance to the project continues. Many Miskitos miss their lost freedom.

“Ours is a complex dispute with the Sandinistas,” said Armstrong Wiggins, 32, who was selected by his Miskito village to represent it in a diplomatic liaison position when the new revolutionary government assumed power. He now lives in exile in the United States with his wife and infant son.

“I was chosen by my people to represent them in Managua, because I had gone to school abroad and in Leon, Nicaragua, with many who later became Sandinista leaders,” said Wiggins, who holds an engineering degree from the University of Michigan.

“The greatest problem is that the Sandinistas insist on seeing the Miskito conflict as a military problem instead of as a social, political and cultural problem. But it is a political problem. They could begin by respecting our land rights. Even Somoza did that.

“We wish to live in our traditional way, on our traditional lands. We do not oppose the Sandinista government,” he added. “We are willing to be allies; we ask only that they respect us, our land, and our right to live as we wish.”

The question of land rights makes Nicaraguan officials a bit testy. “We aren’t giving away half of Nicaragua,” said one official in Managua.

“The Miskito are caught between the ambitions of several different governments,” Wiggins lamented this fall. “We are being used by and for the interests of others. The situation in Honduras is no better than in Nicaragua. Both are unnatural to the Miskito. Miskitos don’t want to choose between one type of camp and another. We want to live as we always have. Our whole lifestyle is under threat. Even human-rights people don’t really understand.

“The people are very scared now. They are battered, intruded upon. Up to now, the Sandinistas have been willing to negotiate with Reagan, but not with other Nicaraguans–the Miskito. In the end, I’m afraid, just as always, the loser will be the Indian.”

“The Sandinista government has accused the church of cooperating with the Honduran government in border attacks,” said Dr. John S. Groenfeldt, retiring director of the Moravian Church World Mission board in Bethlehem, Pa. “That is simply not true. But the Sandinistas suspect the church. They blame it for their border troubles. Now we have pastors in exile, others under arrest, Miskitos relocated, and pastors restricted from ministering to them in resettlement camps. The situation is deteriorating rapidly.”

Some human rights workers and UN officials say privately that if the United States would leave the Miskitos and the Sandinistas to settle their own difficulties and would stop sending arms into the border area between Honduras and Nicaragua–arms that some Honduran military men claim are passed along to the guerrilla fighters–a peaceful resolution could be worked out.

Toward that end, the Moravian church has called on the Reagan Administration to cease support for military action against the government of Nicaragua and to prohibit the training of Nicaraguan dissidents in the United States. The church has also endorsed legislation supporting those aims.

Further, the Organization of American States Human Rights Commission has agreed to try acting as mediator between Miskitos and Sandinistas at the invitation of the Nicaraguan government.

In the meantime, however, government officials have become harder to contact about the issue and it is more difficult for journalists to spend time at settlement sites. Recently, reporters waiting weeks to make the trip, traveled three-and-a-half days overland in government jeeps to be allowed only 30 minutes of conversation with settlement residents at three locations. Government representatives, however, were available at the sites. Officials cited impressive statistics about progress since May, lamenting the murder of road and utility-line workers by counter-revolutionaries. They also admitted that mail to Miskito settlement residents is searched and said that Miskitos are now free to leave the sites if they sign a form relinquishing claims to government-provided housing and services. No forms were available for examination.

Still, the arrival of visitors was a treat-and a chance to pose for pictures. Many mothers rushed home to spruce up their children or to change clothes themselves. One of those was Norma Martinez, recently returned from an unprecedented personal trip.

Disturbed by unreliable mail service and more than a semester’s separation, Martinez decided to see for herself how life in the big-city school was treating her two oldest girls, part of a group of 57 Miskito scholarship students studying near Managua. So, leaving her household in the care of her 13-year-old daughter, she trudged for three days down the dirt road until she was fortunate enough to catch a ride to Managua.

“I didn’t know what might happen to me, if they’d kill me out there or what, but I had to go,” she said. “When the comandante first suggested that they go off to study, my husband and I were very opposed to the idea. But the girls were crazy to go, and eventually we gave in. I found them healthy and happy, there with the other children from here.”

Martinez had never been away from home alone before. In fact, until early last year, she had seldom left her small village. Since then, her footsteps have cut new paths. For her family, as for so many others, traditional ways are finished.

©1982 Mercedes de Uriarte

Mercedes de Uriarte, assistant editor of the Opinion Page on leave from the Los Angeles Times, is studying social change in the U.S. and Central America.