a conciliatorfor the Luyin neighborhood.

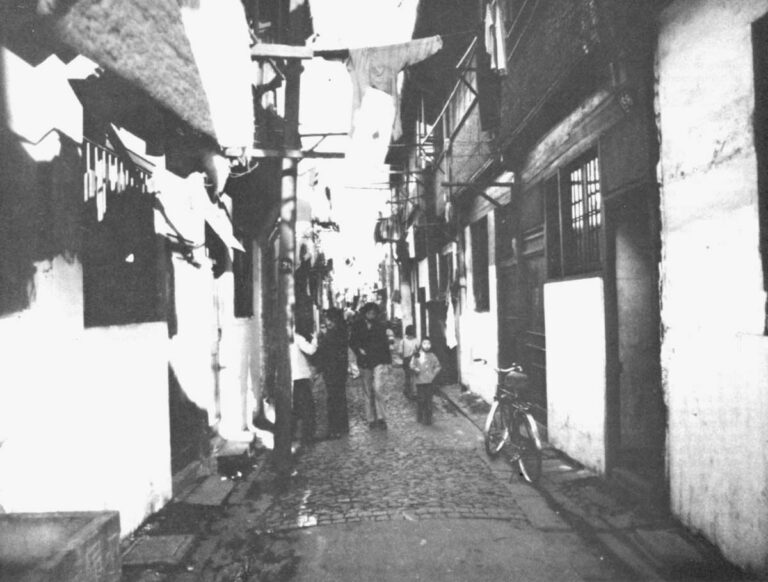

(Photo by Tia Schneider Denenberg)

SHANGHAI–Wang Chenwen is retired now. His closely cropped hair is stark white, and the smile that beams from behind the heavy eyeglasses furrows his face deeply. The few English phrases that have stayed in his memory were lodged there more than 40 years ago, when he worked for a wine merchant, one of the foreign businessmen who then dominated Shanghai’s brisk commerce. But, despite his years, if anything goes wrong on Dong Jiadu Street, in the city’s old section-if the neighbors began exchanging insults over a missing bicycle or blows over a leaky faucet-it is his responsibility.

Mr. Wang is not a policeman, nor is he the venerated neighborhood sage. Keeping the peace is his job because the people on Dong Jiadu Street have made him the chairman of the Neighborhood Conciliation Committee, a unique organization-half official body, half volunteer activity-that helps ameliorate the tensions and frustrations of a society living at close quarters with itself. Mr. Wang has a good deal of help; three other men and five women, mainly retirees like him, act as conciliators for the street and the surrounding neighborhood of Luyin. But it is still a complex task, for Luyin embraces more than 1,000 households and almost 5,000 people, inhabiting low-rise apartment buildings where less than four families to one kitchen would be considered luxurious accommodations.

“Mainly,” says Mr. Wang, “our work is prevention. We go around preaching a simple idea: neighbors should live together in peace. The less time we spend on cases, the better. But we get plenty of those-54 in the past year-mainly civil disputes and minor assaults. They mostly stem from arguments about who should occupy common areas in the buildings and yards, about who left the water running and who uses too much electricity. Sometimes youngsters don’t get along with each other or with their parents. Husbands and wives may be at odds.”

The conciliation committee combines the functions of a board of mediation, a social welfare agency and a rescue squad. It is to the Chinese legal system what the barefoot doctor is to the medical system. Mostly the conciliators talk-cajoling, coaxing and persuading. The committee serves as an intermediary, helping to open direct negotiation between warring families or factions. When all else fails, when the antagonists themselves cannot agree on a solution to their dispute, the committee may suggest a solution, based on its own notion of a fair outcome. But the committee lacks enforcement power, apart from the indirect sanction of public opinion, and anyone unhappy with the committee’s handling of the dispute can take his case to Shanghai Municipal Court. It is a system peculiarly adapted to urban China, where the very shortage of space creates social obligations. The ties that bind the individual to his neighbors are so strong that few “private” disputes would not quickly become matters of public concern.

Although the conciliators are unpaid, they occupy a distinct niche in the city’s table of organization. Mr. Wang’s group is technically a branch of the Luyin Residential Committee, which is subordinate to a Neighborhood Office. The office, in turn, is a subdivision of the Nansi District, one of ten districts into which Shanghai is divided. In a conurbation of more than 11 million persons, the largest city in the world, the conciliators thus represent an arm of municipal government that may touch the average person most intimately.

If a fight does break out on Dong Jiadu Street, the combatants are likely to be visited by a delegation of two or three conciliators, usually including someone acquainted with those involved. “Basically we are looking for justice,” says Wang. “We will reason with both sides. If we favor one side or the other unjustly, the dispute will erupt again. But we have good rapport. We are the elder generation, and we watched the younger people grow up. We know them, and they know us. When we come along, we can tell them to settle down, and they listen to us.”

(Photo by Tia Schneider Denenberg)

But conciliation is not exclusively the province of the elderly. Among the dockyards along the Huangpu, the broad river that gives Shanghai access to the Yangtze River and sea, there is a neighborhood called Xin Madou. The chairman of its conciliation committee is Sung Qishien. A shipyard worker’s wife in her early 40s, Mrs. Sung has a curly permanent, a hairstyle that has become popular in trendsetting Shanghai but which is almost unknown elsewhere in China. Her amiability is tempered by a firmness of tone that obviously compensates, in her duties, for her relative youth. “Originally, I was employed in a workshop in the neighborhood,” she recounts, “but there were problems with youth gangs and other matters. So I was asked by the residents to head the conciliation group. The workshop agreed to keep paying my salary. At the beginning I felt embarrassed because people said I was too inexperienced. I found it difficult to visit the families who had to be seen. But people eventually realized that I was fair, and that was more important than anything else.”

The conciliators are chosen at neighborhood conventions to serve terms of up to two years. They are selected, as one official put it, “from among those whom the people consider most reliable.” Some eventually serve multiple terms. Most of the training is simply on-the-job, and what the members do not learn personally they learn from each other at monthly meetings in which they tabulate their successes and failures. Twice a year they report their activities to the Neighborhood Office, giving a summary of each case.

The work is not without its perils. “Sometimes when we are stopping a fistfight, we get hit,” says Mr. Wang. “When it’s a case of minor injuries, we feel we can settle the matter. But if an assault results in broken bones, or if weapons are used, or if there is an attack by a group of people, then we call in the police.” In such instances, the disputes goes to criminal court. But the conciliators pride themselves on keeping the vast majority of disputes, both potential criminal cases, divorces and civil disputes, out of court. Government officials, in fact, credit the committee with resolving 10 disputes for every one that reaches the formal judicial system.

One person who is grateful for that success ratio is Li Shutang, the acting executive director of the Shanghai Lawyers Association, the equivalent of the bar association. By his estimate, there are only 90 persons in the city qualified to be members of the association-that is graduates of a law school. (By comparison, New York City has 55,000 lawyers for its smaller population.) Without the efforts of Mr. Wang and conciliators like him, that tiny band of litigators, spread over the city’s millions, could be under severe pressure to, as Mr. Li puts it, “serve the masses.”

Yet, even if there were a fully-manned judicial system, many Chinese experts contend, most people would prefer the informal methods of the conciliators. “People like to solve disputes through the conciliation groups because they save time, money and energy,” says Xu Hegao, a director of legal research at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing. “Equally important, perhaps, they prefer conciliation because it protects their privacy. What’s more, since the conciliators know the families involved, understand the personal backgrounds of the people who are in conflict, it’s relatively easy for them to analyze the situation-at least easier than it is for a stranger.”

The committees are also valued for their impeccable revolutionary credentials as the forum of the people. The Chinese trace the committees’ origins to village elders who settled disputes among the peasants too frightened of the mandarinate to bare their private feuds in court. The committees became official revolutionary organs in 1942, during the period when the Chinese Communists were insurgents headquartered in the caves of Yenan in the northwest. They were part of Mao’s plan for governing “the liberated areas,” a technique for promoting solidarity and avoiding squabbles that distracted from building the new order. (There was a hiatus in their development, however. Like many Chinese institutions, the conciliation committees largely ceased to function during the years of the Cultural Revolution, from 1966 to 1973. In a period of general upheaval, peacekeeping was inevitably pushed into the background.)

The social costs of unresolved disputes still seem to be uppermost in the minds of Mr. Wang and his committee members in Shanghai, where the conciliation system has evidently reached its fullest expression. They believe that disgruntled neighbors make disgruntled workers when they arrive at the plant the next morning, diminishing productivity. So Mr. Wang’s committee often enlists the aid of the equivalent of the shop steward at the workplace to help resolve contretemps. To a Westerner, that may seem outrageously intrusive, but in the Chinese context, where work generates not merely a salary but also a sense of mutual responsibility-much like neighborhood ties-it makes sense. A high ranking editor of Shanghai’s newspaper, the Liberation Daily, which avidly covers the work of the conciliation committees, notes approvingly that the workplace sometimes becomes deeply involved in a worker’s domestic squabbles. “If a husband and wife were having a dispute,” says Wu Yuenfeng, “it’s not necessary to go to court. The two factories will mediate between them.”

Marital disputes are, in fact, among the most difficult the conciliators face, and they are notoriously time-consuming. A former conciliator recalled shuttling back and forth between a husband and wife for more than a year and a half. But, he says, with evident satisfaction, “It’s now seven years later, and they are still together. In these cases, I would have to admit that we are subjective: we believe people should stay married.” His perseverance apparently is not atypical. Says Mr. Li, “Perhaps 20 or 30 times in the course of a dispute, the conciliators might visit the families or invite them to the committee office.’

Mr. Wang’s committee uses as its office a room lit by a bare fluorescent bulb in an alley between two residential buildings. It has a long table, numerous chairs and the atmosphere of a recreation hall, but through its red door pass the angry and embittered, seeking satisfaction. Many of these disputes erupt from the volcanic stratum of personal conflict that underlies any society, but some offer particular insights into the everyday life of the people of the People’s Republic.

These are a few of those cases, as Mr. Wang describes them:

Case #1 The Power Struggle

The Liu family and the Hang family live in a building where there is a set of electric meters. They tell how much each family uses so that its share of the cost can be determined. The Liu family suspected that the Hangs’ meter was faulty and didn’t register as much as they actually used. So a member of the Liu family cut the wires to the Hang apartment. It was just before the Chinese New Year celebration—a very inconvenient time for the power to go out. Well, the Hangs went to the conciliation committee, and we got the wires reconnected for them. But they were worried because a family wedding was scheduled to be held in a few days. They thought the Lius might cut the wires again, embarrassing them when they had guests. What did we do? We went to the Lius and said, “We will have the meters tested to see if your fears are true.” We found that even though they looked different, the meters registered equally. And that ended the feud. If we had to, we would have even arranged for the meters to be repaired,- we’ve done that before.

Case #2 Nursing Her Wounds

The Chang family lives next door to a woman, a nurse, with whom they share a water tap. One day the nurse scolded Chang’s son because he was taking too much time at the tap; she wanted to use it. The next day Mrs. Chang and the boy went to her to complain. There was an argument and a scuffle in which the nurse was injured. She said she was unable to work as a result and spent 140 days away from her job, plus more than 100 yuan [about $70] for medical care. She wanted the Changs to pay for all this. We investigated and found that the nurse was exaggerating how badly she was injured. Her x-ray was normal, and the doctor said she only needed two weeks of rest. We asked the Chang family to pay $30 toward her medical expenses, which we thought was a fair share. We also went to her workplace and asked them to persuade the nurse to return to her duties and stop pretending she was an invalid.

Case #3 The Runaway Chicken

The apartment of an elderly woman, a grandmother, was invaded by a chicken, belonging to a neighbor’s child. The chicken ran through the doorway and jumped on the table, making a mess. The grandmother started beating the chicken with a stick to chase it away. The boy came in, crying, “Don’t hurt the chicken!” The grandmother pushed him out and shut the door, but he opened it again quickly–right in her face. Her head was bleeding from the blow, and she had to be taken to the hospital. The conciliation committee knew there would be worse trouble between these neighbors unless we patched things up. So we got the boy’s family to pay her 4 yuan medical bill and promise to watch their child more closely. To make the grandmother feel better about it, the committee sent her a nice plate of steamed dumplings.

Case #4 The Phantom Rival

There was a young couple in their 30s who were always fighting. Finally, the wife applied for a divorce because he beat her. It turned out that he beat her because she got angry at him when she thought wrongly that he had another woman. It took us dozens of visits to straighten this out, but now they get along well. We made a real effort on that one, because they had two children and we felt that the divorce would be bad for the youngsters.

In her nine years on the conciliation committee, Mrs. Sung has also seen many cases. She remembers this one most of all:

Case #5 The New Neighbors

The Wens lived on the first floor but used a room on the second floor to store coal for their stove. When a new family, named Li, moved to the second floor, they claimed the room as their own and asked the Wens to remove the coal. Pretty soon the members of both families were engaged in a brawl. The Li boy grabbed a cleaver. He never used it, but one of the Wens accidentally was cut during the pushing and shoving. She stayed home from work and wrapped her hand in a huge bandage, just to show off. Soon the whole neighborhood was full of rumors that the Li boy had chopped her hand off. We couldn’t get them to cool things off so we went to their work units. After two months, what we came up with was this: the Li family would pay the medical bill and both families would divide the loss of work time between them, each side using up some of its sick leave. Eventually, we got one of the families to move to prevent a recurrence. It’s not something we can do very often, because housing is so scarce.

China’s legal system is changing rapidly. A new legal code has recently been promulgated, and the supply of lawyers is being enlarged. (The Shanghai bar expects to expand from 90 to 300 full-time law graduates by the end of 1982). China is moving slowly toward acceptance of a notion that Americans take for granted but which, in China, is stunningly novel. As Mr. Hu of the Academy of Social Sciences puts it: “Even the state should obey the law, and every person, high level or low level, should be liable to be taken to court by any other person.”

As part of this reform movement, Mr. Hu, Mr. Li and five other lawyers visited the United States recently on a fact-finding mission to study the American legal system. But like Chinese modernizers of all eras, they saw some foreign ways that attracted them and others that they considered incompatible with Chinese values. Their delegation was impressed, Mr. Li said, by the scope and quality of legal training; they were less impressed by what they saw as the unremittingly adversarial quality of the American system, the tendency to magnify and polarize conflict rather than to assuage it.

For that reason, the conciliation committees, which strive for compromise rather than confrontation, are an aspect of the past that will probably survive the modernization campaign. Until recently, China’s strong attachment to the committees has been, to some extent, making a virtue of necessity. But the Chinese now believe that conciliation is a way of settling disputes superior to courts, even under ideal conditions. “Conciliation is especially necessary because there are relatively few courts,” says Mr. Li. “But there will always be a place for it in our legal system. We consider it important for people not to have conflict in their lives.”

©1981 Richard V. Denenberg

Richard V. Denenberg is investigating “Alternatives to Traditional Courts.”