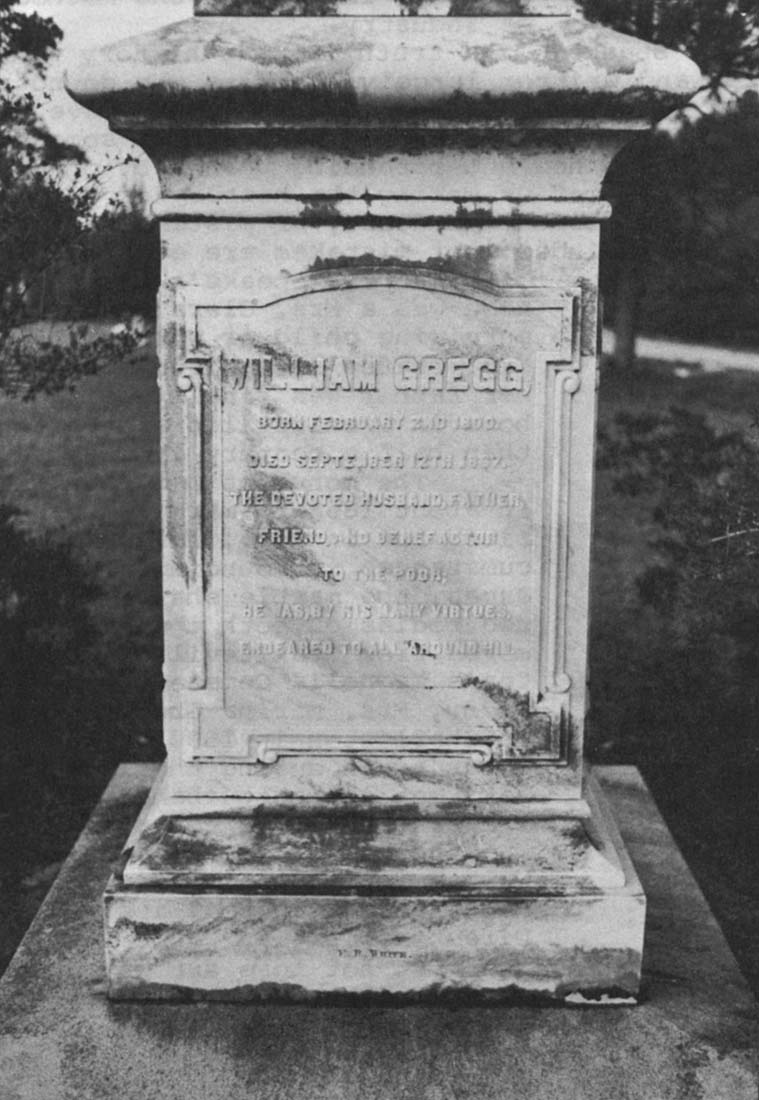

On a high sandy hill of long-leaf pine and scrub oak marking the rim of South Carolina’s Appalachian piedmont as it begins its descent into the tidewater delta, there stands in the middle of a small clearing a 14 foot white marble shaft dedicated to the memory of William Gregg, 1800-1867. The monument was unveiled on June 14, 1926 on this spot in honor of one of America’s earliest guerilla fighters for industrial capitalism in the heart of the Ante-Bellum South. Three hundred feet below and less than a mile down the winding road from Kalmia Hill, so named for the mountain laurel that once covered its slopes, lies the town of Graniteville, William Gregg’s single-handed industrial revolution to which he gave his life.

Graniteville lies tucked within a tiny deep-cut valley carved by Horse Creek as it makes its way south over twelve miles of watershed to Augusta and the Savannah River. Graniteville is a milltown, with a large two-story cotton factory at its center built “in the New England manner” out of huge blocks of local blue granite quarried from the surrounding hills. Historians may quarrel about whether Graniteville’s long standing reputation as the “first great cotton mill in the South” is deserved, but nobody since its inception in 1845 has disputed the fact that this isolated mill village of 100 cottages and a granite factory in the backwoods of south Carolina was certainly one of the most controversial industrial experiments ever attempted in the history of the South. At a time when Horse Creek Valley and its people were, in the words of Gregg himself, “little above the Indian” and the South as a whole was still viewed by its planter aristocracy as one vast cotton plantation, Gregg set out to prove the extraordinary hypothesis that free white (i.e. wage labor) factories were not only perfectly compatible with the traditional plantation system, but were absolutely essential to its political and economic future.

June 14, 1926: “We bring the monument of William Gregg back to Graniteville because Graniteville is his monument. However beautiful the spaces of earth, no place can be to us so attractive as the spot consecrated by life’s supremest sacrifices. The foundations on which we stand William Gregg laid in the faith of us and in the tragedy of suffering. This act indicates that we are beginning to see what he so clearly saw more than three quarters of a century ago. If the light waves have been so long a time in breaking upon us, they have had to travel a very far distance. We have followed the star of empire and lo, it has led us to Kalmia, whence we started and we bring today gold, frankincense and myrrh.”

The speaker is Dr. J. W. Speake, the secretary of the South Carolina Methodist Conference, and the occasion is the official unveiling of the Gregg monument on Kalmia Hill above Graniteville. According to the Augusta Chronicle, the program consisted of songs by high school pupils of the town, many of whom were great grandchildren of former employees of William Gregg. The opening prayer was offered by the Rev. 0. E. Te Bow of the Graniteville Baptist Church, and then Mr. Lanier Branson, President of the Graniteville Manufacturing Company, introduced the Methodist Secretary of Industry.

Dr. Speake: “The truth is, the history we know and read was made and written largely by those who do not share our point of view. We in all likelihood would have held with them but for the light of events that have for some of us flashed a spotlight of new understanding upon many of the pages of our history. Those of us making the history of our present order are in the presence, no doubt, of mistakes as tragic as those behind us, if indeed our mistakes are ever behind us.”

At Dr. Speake’s side that Sunday afternoon was a Mrs. Clara Gregg Chafee, the only surviving child of William Gregg. It was with Mrs. Chafee’s permission that the monument to her father was finally being returned to its home in Graniteville after standing for more than half a century in Charleston.

The monument had been first erected here in about 1868 to mark Gregg’s original gravesite. But in 1876, following the tragic circumstances surrounding the death of Gregg’s son James, the marble shaft along with the disinterred bodies of both the father and son were removed from Graniteville and carried to Charleston’s Magnolia Cemetery at the request of Gregg’s widow, Mrs. Marina Gregg. Mrs. Gregg herself died in Charleston in 1899 at the age of 88 having never again during the last 25 years of her life set foot in her husband’s beloved Graniteville. The ownership and control of the Graniteville Manufacturing Company, following the deaths of William and James Gregg, passed quietly into the experienced hands of its Treasurer and Board of Directors.

Dr. Speake: “We must not lose our way in the discussion of institutions that seem for the moment secular. The tragedy of the world is that we have not even as yet learned that there is no secular or sacred as apart. A1l social and economic relations are converted into language, values, literature, morality and religion. Indeed the ultimate end of all social relations must be that man may come to himself enriched, perfected, complete–thinking the true, willing the right, loving the good. This is and must be the key to judgment upon all social and economic institutions and the measurement of politicians and statesmen.

“Economic and social forces wage wars and conquer one another after the manner of ancient kings. Economic slavery may be worse than chattel slavery as indeed it was with us. To be a chattel slave, cared for, appreciated, possessed and ofttimes loved, is vastly preferable to illiteracy, social ostracism, unloveliness…We may still be in the wilderness, but we are no longer in Egypt. We at least have come far enough to teach our children the cause of our economic failure, to explain to their bewildered minds the cause of their mother’s inability to read or write, and to teach them to reverence those who have given them this larger world in which they live.”

William Gregg’s monument stands on the southwestern end of Graniteville cemetery. By now the memory of the day it was returned is dim in the minds of Graniteville’s elder residents, even those who were there to see the ceremony. Today the clearing on the hill is crisscrossed with the tire tracks of pickups backing through the mud to slide garbage off the rim of the plateau into the scrub forests of the valley below.

They call it just the Valley now, Vaucluse down to Graniteville and Warrenville, further down through Langley, Bath and Clearwater into North Augusta. Cotton mills, rayon mills, textile-chemical, dyeing and finishing plants crouch in the sand hills behind K-Marts and McDonalds along the four-lane connecting Aiken and its golf courses with the heart of downtown Augusta. Long before Erskine Caldwell’s proletarian sentimentality helped make Horse Creek valley’s so-called “poor white trash” and cotton mill “lintheads” into American household words, the Valley had become a symbol of the stigma attached to textile millwork throughout the South.

But Graniteville’s residents don’t take too kindly to such stereotypes. They are a proud and forthright people, knowledgeable about their history and quick to point out that the Valley and its mills have been the backbone of Aiken County and before that Edgefield District for over five generations. Their parents and grandparents before them worked in the cotton mills, many at the same jobs their grandchildren and great grandchildren have today. Many were born, raised and died in the same company houses and were buried in the same family plot as will their children and their children’s children. Even those that move away, they say, come back to Posey’s Funeral Home to be buried in the family ‘square.’

For Graniteville is a town that believes in its ghosts, welcomes them as family: whether it’s a great grandfather, long dead and buried, back to squeak his ancient porch rocker on a hot still summer evening, or locked doors that open in the night to a kitchen whore once long ago someone’s grandmother burned to death in a fire. In the evening after dinner over coffee, the town seems to shake out its ghosts like pecans from the trees in the garden. Night dogs bark the distance between houses like old friends calling out across a field each one’s too tired to cross, and old stories weave their way through the sleep of whole families, whole generations of families, until the history of an evening becomes the history of a town and of a century.

“My wife’s uncle was here when it happened, and he used to tell my wife about it. He lived to be 101 years old and was living at the time it actually happened. He knew the boy,” muses Ansel Thompson to a stranger on one such evening. Ansel is a skilled mechanic and loom fixer who retired in 1970 after 47 years with the Company.

“Well, I never did go into the house. I heard he made his wooden leg and crutch and so forth up there in the attic hidden away. He was a Pegleg, you heard that didn’t you? But as far as knowing anything, I never did go into the house.

“We lived next door to it, and the neighbors would…uh…in the yards and around…uh…but they were much older than we were. Most of the people knew about it when we first come to Graniteville, but nosir I really couldn’t give you any information. Some of the older people who were here would occasionally get in a conversation and bring something like that up. History, you know. They would tell these stories, which were true most of them. But I never was a child to listen to all these fairy tale stories and such. You know what I mean?”

Ghost stories about a strange boy a century ago who murdered the ‘big boss’ Gregg and was buried in the yard of his father’s house. Ansel Thompson never was the child to listen to such fairy tales, and yet to an outsider it seems that most of our social and economic history has thus far been passed down to us in the form of more or less thinly disguised moral tales, fairy tales “after the manner of ancient kings” to teach our children to reverence those that have given us this “larger world” in which we live. Dr. Speake’s flash of new understanding, that was in 1926 to immortalize a little known South Carolina industrialist named William Gregg as one of the South’s first true martyrs in the cause of empire, was, although a bit more rhetorical than most, not untypical of our pre-1929 economic evangelism. During the coming months in these newsletters, I will be exploring both sides of Graniteville’s industrial revolution, that is, both her public mythology of monuments and ceremonial heroes, and at the same time her private underworld of ghost villains and legendary characters, family histories and photographs, each preserved and passed down through the generations family by family in solemn testimony to this extraordinary period in our economic history.

Received in New York on April 7, 1975.

©1975 Richard Pearce

Richard Pearce, a freelance film-maker/journalist, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Pearce and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.