“It was gravely stated to them…that they were all, when they arrived at the cotton mill, to be transformed into ladies and gentlemen; that they would be fed on roast beef and plum pudding, be allowed to ride their master’s horses, and have silver watches and plenty of cash in their pockets.”

— (Paul Mantoux, The Industrial Revolution in the 18th Century, p.411)

I) England 1760-1815.

First there were the pauper children. “Indentured parish apprentices” they were called, indentured from as early as five years old, sometimes even four, until the age of twenty-one. In lots of fifty to a hundred like cattle they were negotiated from the quaint picturesque Dickensian workhouses of 18th century London to the remote factory towns of the north of England, where they disappeared from the public record. As Paul Mantoux, one of the early scholars of the industrial revolution, has put it, “The only extenuating circumstances in the painful events which we have now to recount as shortly as we can, was that forced child labour was no new evil.” True, the 16 to 18 hour working days, the discipline, the lashings, the “well-known catalogue of sufferings” were not new. The English workhouse had made so-called ‘industrial’ torture, i.e, lashing, branding with a red-hot iron, etc. a commonplace by the mid eighteenth century. No. It was not forced child labor that was new. It was something else. It was the combination of the child and the machine. To the workshops of an earlier age were added the “iron fingers,” as Carlyle called them, of the Age of Machinery. Skilled craftsmen were replaced by unskilled operatives, a dozen workmen’s hands by the “nimble fingers” of a single young woman or child. Out of the side of Spinning Jenny, that great machina ex deus of World Civilization textbooks, sprang Manchester and so God created the Industrial Revolution.

Across the Atlantic a young nation of farmers, craftsmen, merchants and planters stood watching with that peculiarly American mixture of awe and distrust, envy and suspicion, as almost overnight the mills of Lancashire turned the entire existing world of commerce on its ear. Whereas in Adam Smith’s England economics had emerged as the new science of the market place with its famous self-regulating “natural laws ” of supply and demand; in Thomas Jefferson’s America it still remained a medieval morality play pitting the legendary frontier American husbandman alone on his farm against all those abstract, alien, socio-economic forces of the European city and its mobs (like “sores” upon the body of pure government begetting a “subservience and venality” that “suffocates the germ of Virtue,” Jefferson wrote in his famous Notes on Virginia).

Even the earliest manufacturers themselves in this country were to voice some of these same misgivings. Nathan Appleton, one of the founders of the famous mill city of Lowell, wrote:

“The operatives in the manufacturing cities of Europe were notoriously of the lowest character for intelligence and morals. The question therefore arose, and was deeply considered, whether this degradation was the result of the peculiar occupation, or of other and distinct causes. We could not perceive why this peculiar description of labor should vary in its effects upon character from all other occupations.”

Or James Taylor, William Gregg’s associate in the creation of the Graniteville Manufacturing Co. of South Carolina, who a few decades later wrote:

“Because an effort has been made to collect the poor and unemployed white population into our new factories, fears have arisen that some evil would grow out of the introduction of such establishments among us.”

What was this strange fear of some “evil” that might grow out of this “peculiar description of labor” called the factory? And who were these crowds, these European “mobs,” somehow threatening to suffocate the “‘germ of Virtue” that was Jeffersonian America?

(“The Indians thought that the horse and its rider was all one animal, for they had never seen horses up to this time.” Bernal Diaz, The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico, p.59).

II) Ireland 1815-45.

Webster’s defines cottier as an archaic term for an Irish tenant on a small farm under the rack-rent system. Rack-rent is defined as rent that is at or near the full annual value of the tenement itself. By the beginning of the 18th century, cottier families already comprised about four-fifths of Ireland’s total population, and potato was their sole subsistence diet (as it was for much of the rest of Europe’s peasantry of that day). But to explain the incredible immiseration of the Irish people during the first half of the 19th century, as most historians tend to do, by simply pointing to the recurring potato blights is like describing people forced to live in a tidal basin as flood victims.

The real story of the fate of the Irish cottier begins with the sudden fall in the price of grains following the Peace of 1815. This took its worst toll, particularly after 1820, on the cottier peasants and made it increasingly difficult for the landlords to collect rents, convincing the gentry that a more profitable use for their land would be to turn it into pasture. And so began the same gradual consolidation of land holdings and wholesale eviction of tenantry that had happened in England over two centuries earlier.

In 1829 the so-called “forty-shilling freeholder” was deprived of the vote, and in 1838 the famous English Poor Law system was instituted by the Irish gentry in order to protect the lives and property of landlords against the growing menace of the dispossessed that seemed to multiply almost daily around them. This gave further impetus to the movement toward consolidation, as before 1838 eviction had been dangerous because the ejected had no place to go. Now under the Irish Poor Laws of 1838 the landless peasant could be, as one commentator has written, “conveniently and safely lodged in the new workhouses.” And since the same law provided for assisted immigration, it was only a step from eviction to workhouse and from workhouse to emigrant ship.”

No longer politically useful and unable to pay rent, the cottier peasant and his family were driven from what little holdings they had and literally placed on the ship that was to carry them on one of the most extraordinary migrations in history. To understand the scale of this social upheaval, for example, during just three years from 1849-51 over a million persons were evicted by Irish landlords. To these vast numbers of newly dispossessed families, the destination mattered little. For Irish immigration during these terrible decades was an exodus, a flight. Oscar Handlin, the noted historian of Boston’s immigrant population, quotes The Cork Examiner: “The immigrants of this year are not like those of former ones; they are now actually running away from fever and disease and hunger, with money scarcely sufficient to pay passage for and find food for the voyage.”

Anderson Friday and Patrick McEvoy were two such immigrants, farm laborers born of cottier parents. Anderson in 1818 and Patrick in 1825. Separately they came on separate ships not to Boston but to South Carolina, up the Savannah River to Augusta and Hamburg, married each a South Carolina girl and soon found their way to what in the census records of 1860 was known as Gregg Township (Graniteville, S.C.).

III) Graniteville 1845-78.

“It is only necessary to build a manufacturing village of shanties, in a healthy location in any part of the State, to have crowds of these poor people around you…who, if too lazy to work themselves, might be induced to place their children in a situation in which they would be educated and reared in industrious habits.”

(William Gregg, Domestic Industry,1845)

“On the very evening of our arrival, having at last withdrawn to the one spare bedroom, my father and mother looked blankly at each other. A chill wind blew in thin, keen streams through chinks in the bare, wooden wall, the geese squawked loudly in the muddy yard…a little unshaded kerosene lamp made the grim room look all the gloomier. My mother sat down on the springless bed, a picture of desolation. The sudden plunge unnerved her….

“She had one consolation that apparently justified the whole adventure. My father was a changed man. From now on and for many years he was full of energy and buoyancy, splendidly patient and brave, always ready to cheer her in her fits of loneliness and depression. He had shaken off the morbid inhibitions and immediately started out into the village to see what he could do.”

“The plan worked well. The houses were soon filled with respectable tenants who paid a fair interest on this part of the capital; and, while the sons and daughters worked in the mill, the father would engage in cultivating his land, hauling wood, etc, and the mother would attend to the housekeeping department….” (James Taylor, De Bow’s Review,1850)

IV) Some Facts.

According to Robert Mill’s Statistics of South Carolina written in 1826, almost all the (white) citizens of Edgefield District, the county in which Graniteville was to be built two decades later, were “planters” who paid little attention to crop rotation so that soil depletion due to cotton cultivation kept the planters “in constant exertion to clear the lands as fast as they are worn out and as fast as the Negro property is increased.” In 1800 whites outnumbered Negro slaves 13,063 to 5,006. By 1820 the number of Negro slaves had increased by almost four times to 19,198, whereas the white population had declined to 12,864. At that time the price of slave labor in Edgefield District was $50 per year while that of white labor was $100 per year. By 1850 the cost of slave labor had surpassed that of white labor and one out of every three white families owned no property at all, until by 1880 in some counties three-fifths of all field work was being performed by whites at wages averaging about $8 a month.

During the 1870’s a precipitous fall in the price of cotton to a point at or near the cost of production forced increasingly large numbers of yeomen farmers into a crop-lien system of tenancy in which farm supplies were purchased on credit from local merchants at 20-100% above cash prices only on the condition that every inch of available land be turned to the cultivation of cotton. Needless to say, as the cotton crop multiplied, inevitably prices fell even further, thus creating more and more tenants with less and less land to devote to food crops for their subsistence. By 1880, according to the S.C. Board of Agriculture Report of 1883, the piedmont region of South Carolina had some 38,591 farms of which 45% were under 50 acres, but only 6% of this total were both under 50 acres and worked by their owners. Crop liens were increasing at an extraordinary rate of 23% a year (from 1880-82) with over half the total growing crop already under lien.

“There is a pressure on us all the time for places…. We are annoyed all the time with wagon loads of people sent here by neighborhood contributions to get clear of them. In many instances they have been abandoned in inclement weather in our streets, destitute of food and clothing, and we have been obliged to administer to their wants and to send them back to the neighborhood from which they came, with our own teams. Sometimes they come by railroad, a poor woman with four or five helpless children, sent here and the passage paid by charitable people, under the presumption that Graniteville is a sort of charity hospital.”

(William Gregg, in a speech to the stockholders on April 18, 1867, shortly before his death).

V) Some More Facts.

In the same S.C. Board of Agriculture report of 1883, the adult “working class” of the state, which had decreased from 359,874 in 1860 to 263,321 in 1870 due to the intervening war years, was defined as anyone over ten engaged in an occupation. According to N.C. law, anyone over the age of twelve was considered an adult. During the week ending July 21, 1849, 82 children worked in the Graniteville Manufacturing Company’s spinning room for a total of 485 hours at a maximum pay of $.30 a day. During the week ending April 9, 1853, in the same spinning room 54 children worked a total of 301 hours for a maximum pay of about $,35 a day

Children under 14 working in cotton mills Peter Barton age 11, Sarah Burkholder age 11, Ellen Bonds age 12, Ida Harrison age 11, John R, Kaitus age 8, Nancy Koeps age 12, Artis Koeps age 13, Mary Elizabeth Sander age 12, Sarah Mundy age 13, Margaret Timmerman age 13, Eliza McDowell age 13, Pope Stothart age 12, Susanna Dubois age 12, Julian Dubois age 12, William Robert age 13, David Sheppard age ll,, James Sheppard age 12, Josephine Entwistle age 12, Mary West Entwistle age 13, Leonard Malone age 10, Alice Connaly age 12, Odelsa Posey age 11, Idela Posey age 9, Nancy Posey age 13, Emaline Howard age 13, Cummins Crocker age 12,, William Bowers age 13, Elizabeth Prescott age 13, Berry Worshum age 13, Sarah Boyart age 12, Frank Gulledge age 12, Ella Glover age 11, Catherine Green age 12, Isabella Green age 13, Sarah Harris age 13, Elizabeth Harvey age 12, David Rhoden age 12, Lucretia Hamilton age 10, James Hamilton age 12, Thomas Timmerman age 11, Pierce Hatcher age 12, Marina Hatcher age 13, Gracey Sheed age 10, William Sheed age 12, William Red age 13, Jepe Key age 13, David Key age 11, Benjamin Koon age 13, Elizabeth Koon age 12, Charles Busky age 12, Jane Busky age 10, David Ergle age 12, Elizabeth Glover age 13, Martha Redd age 12, Luisa Howard age 8, Pauline Howard age 10, Gonzode Fortner age 13, Thomas Busby age 11, Amanda Steifel age 12, Napoleon Steifel age 11.

April 20, 1876: A Serious Shooting Case. James J. Gregg, son of William Gregg the founder of the Graniteville manufacturing Company, was shot and killed while attending a stockholder’s meeting at the company by a Graniteville youth by the name of Robert McEvoy. The shooting was, as far as can be determined, without motive or cause.

VI) He Saith Nothing

Part I. The Story of Bob McEvoy. Graniteville, 1854-78.

“The bad boy of the village was Bob McEvoy. One who knew him described him, ‘He would mold nickels, and it was said he would take Confederate money and raise its denomination by pasting a 2 on top of the 1 of a 10-dollar note.’ Playing about a freight car at the Kalmia station, Bob got a severe injury to his left leg. When Mrs. Gregg knew of it and learned that the wound was infected, she went to the McEvoy home and bathed and dressed the hurt. The leg had to be amputated, and Mrs. Gregg nursed the boy and took him to Kalmia to convalesce. When he was well he had a crutch, in the use of which he was remarkably dexterous. He would go hunting all day through the swamps, and could climb a tree like a cat….”

(“No generalization has much meaning until we have actually examined the constituent parts of the entity about which we are generalizing. No contention about the people on the bottom of society — neither that they are rebellious nor docile, neither that they are noble nor that they are base — no such contention even approaches being proved until we have in fact attempted a history of the inarticulate.”

— Jesse Lemisch, historian).

“One April day in 1876, nobody knows why, he (Bob McEvoy) appeared at the door of the mill office in the main factory building, where James Gregg, then superintendent, was working at a desk. He shot Gregg, fled through the passageway, and swung around the jamb of the door toward the canal, across which he disappeared with uncanny swiftness. one may still see the hole in the door frame torn by the bullet which Gregg sent after him. Gregg died a few days later in Augusta. Mrs. Gregg recorded it in the family Bible that her son was murdered in cold blood….”

The state of South Carolina, county of Aiken, in the general session. The state of South Carolina against Robert McEvoy, indictment for murder, April 9th, 1878.

…and it being thus solemnly demanded of the prisoner Robert McEvoy if he hath anything to say why the court should not proceed to award execution of the judgment pronounced against him…. He saith nothing.

April 20, 1878. The Charleston News and Courier:

“McEvoy was hung at ten before one o’clock in one of the upstairs cells in the jail in the presence of the sheriff and assistants, the priest and the 10 spectators allowed by law, several of them being prominent colored men. The fall was over six feet, and McEvoy without the slightest struggle died in fifteen minutes.

“Many Graniteville people witnessed the execution. One villager, now an old man, told me of seeing Bob’s father drive back to the town sitting on his son’s coffin. He buried the body in the corner of his yard where he could watch over the grave — this out of fear, so the story goes, that doctors would disinter it to dissect the brain, which was admitted to be ‘a powerful one.’ ‘After times and times,’ my informant concluded, ‘the mound disappeared — old man McEvoy had moved the body himself, nobody knew where to.’” (from a footnote in William Gregg, Factory Master of the Old South by Broadus Mitchell)

“My wife’s uncle was here when it happened, and he used to tell my wife about it. He lived to be 101 years old and was living at the time it actually happened…. Most of the people knew about it when we first came to Graniteville, but no sir I really couldn’t give you any information. Some of the older people who were here would occasionally get in a conversation and bring something like that up. History, you know. They would tell these stories, which were true most of them. But I never was a child to listen to all these fairy tale stories and such, you know what I mean?”

(Ansel Thompson of Graniteville talking about the story of Bob McEvoy)

VII) He Saith Nothing

Part II. The story of Tom Friday. Graniteville, 1879-1943.

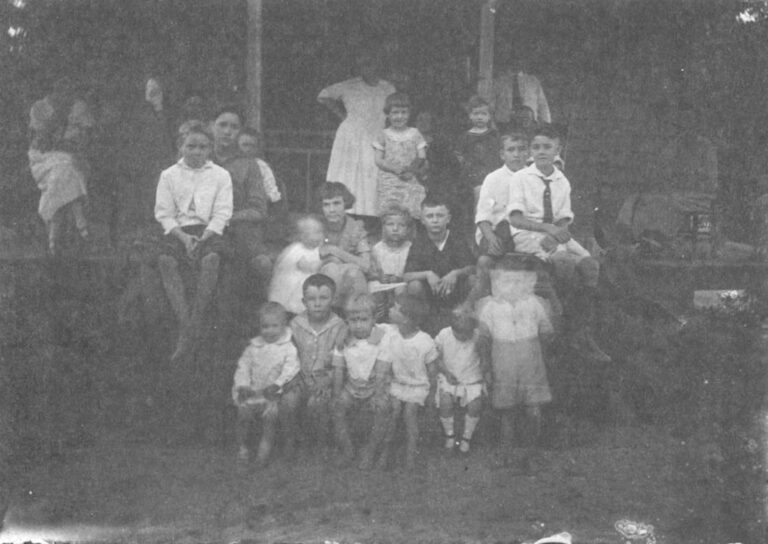

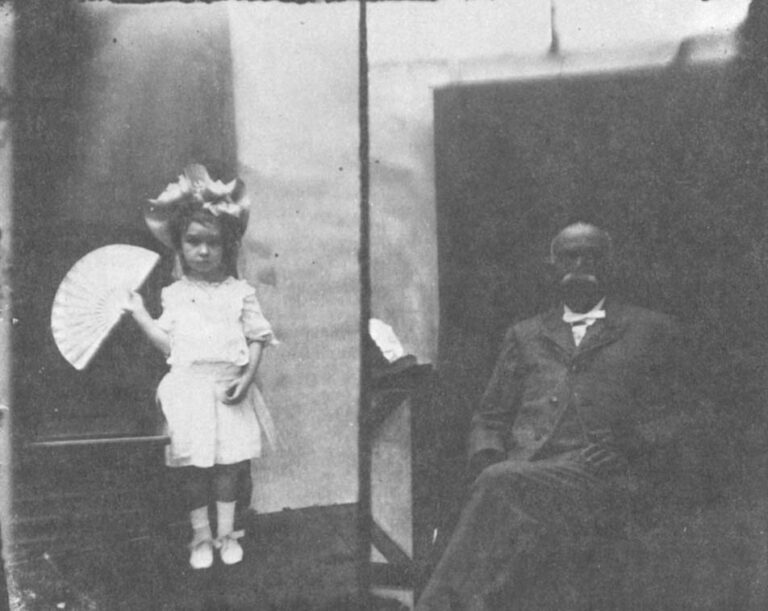

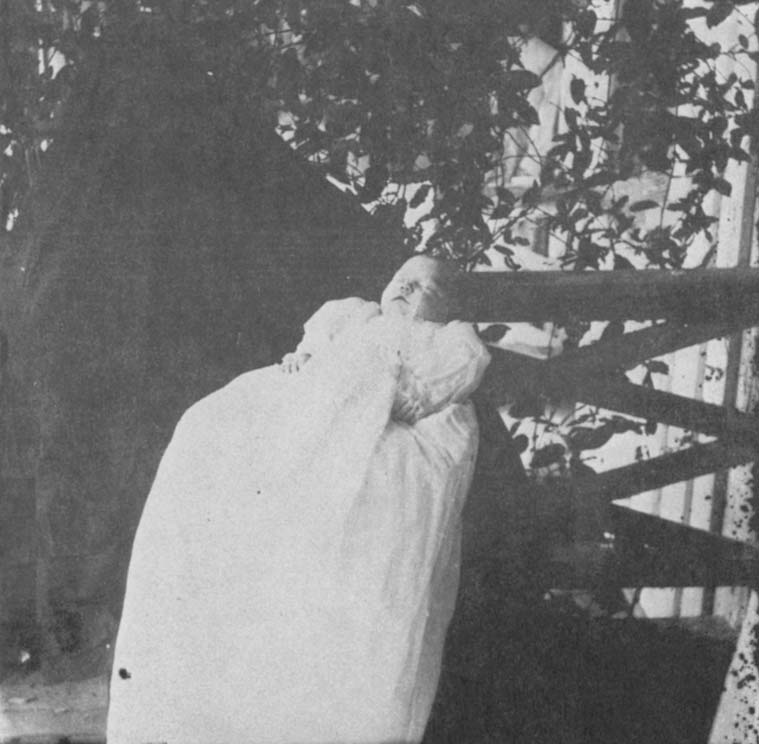

Cloutezze Friday Johnson (age 72) daughter of Tom Friday: “They say it’s a sign of age. I ramble every night when I get kind of lonesome and I get tired of crocheting and I get tired of T.V., so I start rambling into some of these old photographs of his.”

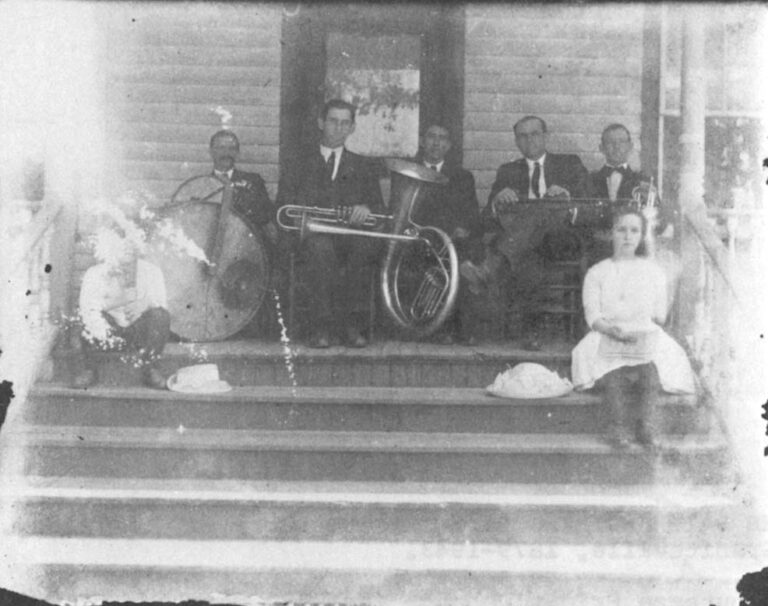

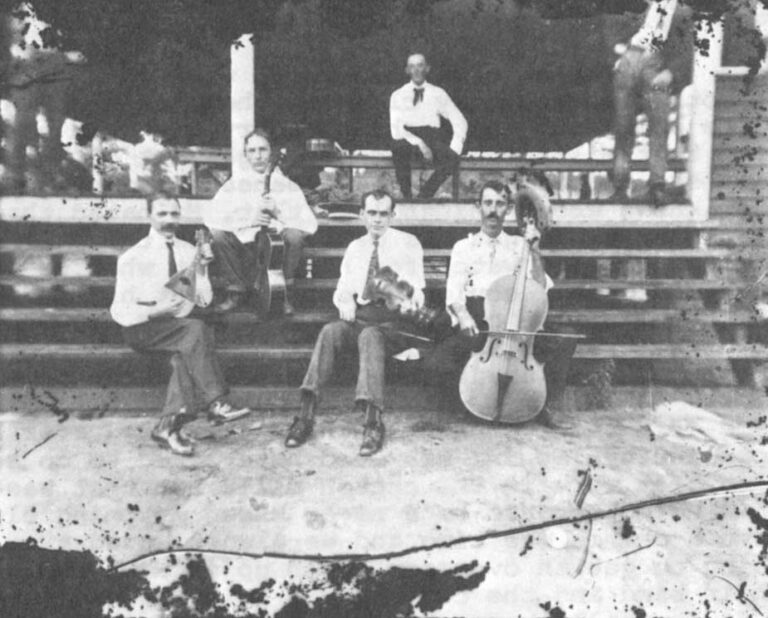

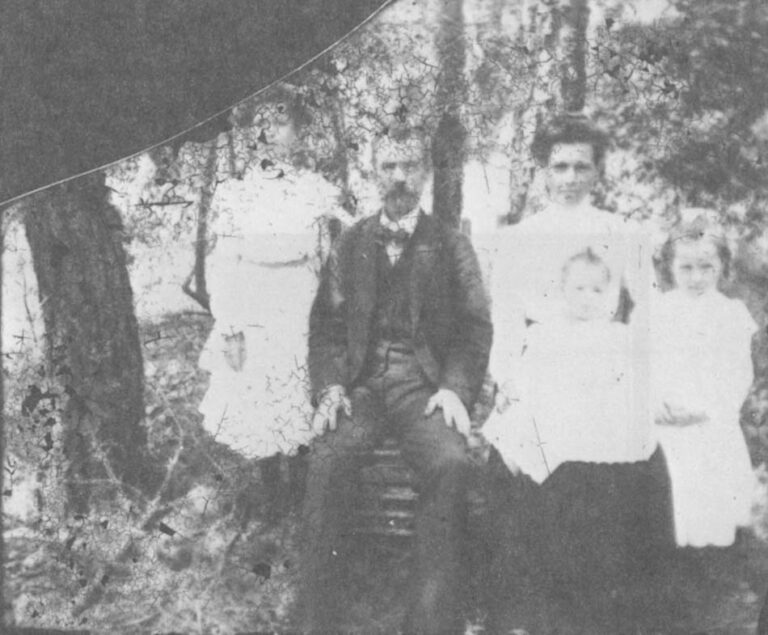

“He used to love to take these pictures. I can see him now working on his pictures out in the yard. He used to print them in the sun you know. And on Sunday he would go all over the village taking pictures of people’s children and of their families. There was one time when almost every family in Graniteville had a picture taken by my father. That and his music. Every day when he came home from work that is what he did. Make pictures or practice that horn, those two things.”

“That was in the days when Aiken used to be a famous tourist resort and millionaires used to come there from all over the country. My father had organized a band and they had a big wagon with a team of horses and they’d go up to Aiken to play for the big dances up there during the winter. It seemed like it was almost every night although it must have been no more than two or three nights a week. You know in those days they worked in the mill six or seven days a week. Well he’d get back early in the morning and then have to get up and go to work after just two or three hours of sleep.

“During the day at about 11:30 there would be this warning bell for dinner carriers. If we were in school, they’d let us out at 11:30 to come home and get the dinners to take to the mill. I used to go down to the card room where my father worked and take him his dinner and while he was eating I would look at all the things they do and wonder what it was all about.”

“You know when I was little and I heard my daddy talking about having to go to work to make some money, I thought he actually made money in that mill. I didn’t know they made cloth down there. I thought they made money you know like in a mint and that he just brought some of it home with him.”

“My father always liked to wear white clothes. Kept my mother pretty busy cleaning them for him. White pants, white shoes and white shirt. Every day when he came home from that mill he used to get right out of his old work clothes. He was one of the cleanest, tidiest people I’ve ever known about things like that. He hated that cotton lint that would get all over him from the mill. I used to love it. I’d watch for him so that when he was coming down the path I could run out and meet him and pull off all the lint and put it on me. And held say you wouldn’t be doing that so fast if you know where that came from. I can hear him saying that, laughing about it.”

“In fact, though, I think if he had ever had the opportunity I think he would have liked to do something else than work in the cotton mill. But that was all he knew to do because had never known anything else. He did have a chance one time and we almost moved away. He was going to get an overseer’s job up in Newberry and direct their band and the company was going to back that band up. I don’t really know why he didn’t take it, only that my mother didn’t much want to go. So that must have been the reason I guess. But I don’t know, he never said. She loved her family. She felt like she wanted to stay close to all her people, and he didn’t want to do anything to displease her. And he might have been a little bit afraid for fear he wouldn’t like it or something would happen. I don’t know why, but I know we were just about ready to move in a week when all at once we weren’t going to.”

“In fact, though, I think if he had ever had the opportunity I think he would have liked to do something else than work in the cotton mill. But that was all he knew to do because had never known anything else. He did have a chance one time and we almost moved away. He was going to get an overseer’s job up in Newberry and direct their band and the company was going to back that band up. I don’t really know why he didn’t take it, only that my mother didn’t much want to go. So that must have been the reason I guess. But I don’t know, he never said. She loved her family. She felt like she wanted to stay close to all her people, and he didn’t want to do anything to displease her. And he might have been a little bit afraid for fear he wouldn’t like it or something would happen. I don’t know why, but I know we were just about ready to move in a week when all at once we weren’t going to.”

“I’ve always wondered if it wasn’t…you know some people have a way of just going along…. My daddy was like that. He would do what he was supposed to do. He was honest, but he wasn’t going to get down and lick anybody’s boots in other words to get there. He was that type of person. If they didn’t see that he was doing a good job at what he was doing, that was their problem. A slubber tender in the card room, that’s what he was. All his life. He never got anywhere. I often wish he had gone and taken that other job just to see what he could have done. As I got older I’ve thought about it a lot because that was as good a chance as he ever got. If he’d gone he might have gone places maybe, with his music especially. I don’t know whether it was a fear of not having enough for the family or fear to venture out. I guess I’11 never know why.”

“My aunt Miss Lizzie, my father’s sister, used to worry him so! Once when there was a strike, she went with the strikers and my dad wouldn’t. And they kind of broke relations for a long time over that. She was highly offended because he wouldn’t join with them. He told her he had a family and he had to go to work to make a living for them. He said he thought some of the things about it might be all right but that by staying out on strike he would probably lose more than what he would gain even if they won. He used to worry about her so because she was so staunch about this union thing. She’d say you’re not sticking with us. We could win this and get what we’re asking for if you’d help. After a while they finally all went back to work though, and they got a raise. But for a long time Aunt Lizzie wouldn’t have a thing to do with my dad.”

“A strange thing happened on the Christmas just before he died. He had been sick for over a year. Soup and baby food was about all he could eat and even that would pain him so bad we’d have to give him all kind of pills to even quiet it at all. Well it was Christmas and my mother had cooked a big Christmas dinner. We were all at the table when he came down from upstairs and sat in his old chair. He looked around the table at all of us children and then he turned to mother and he said I want some of that food and I’m gonna eat some of it regardless.”

“All of us at the table got real quiet because we all knew how sick he was. And Momma at first just looked at him until she saw that he really meant it and then she filled him a plate and handed it to him. Things he hadn’t been able to eat in more than a year. We were all scared to death because we were sure it would kill him dead on the spot.”

“Well do you know he ate a hardy dinner and it didn’t seem to hurt him a bit. He lived from that day to the 19th of January and if that dinner ever hurt him we didn’t see any sign of it. It’s strange…. It’s always been a puzzle to me how he could eat that meal. I can remember it clear as day the way he sat there in silence, all of us not breathing a word, and ate him that meal. I say the good Lord must take care of people, but it sure is strange how things like that work.”

All the photographs in this newsletter are by Tom Friday (1879-1943). Printing from glass plate negatives by Susan Meiselas and Dick Pearce.

Received in New York on October 15, 1975.

©1975 Richard Pearce

Richard Pearce, a freelance film-maker/journalist, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Pearce and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.