It is possible that a working class man may be able to negotiate passage into mid-life with less crisis than a middle management executive, who may feel the storm earlier-and even die from it.

Two boats lie at anchor in the same harbor of a Saturday afternoon. The skipper of the cabin cruiser, seventh vodka-and-tonic in hand, has spent the day embalming; his insecurities while he and his wife entertain the company officer whose job he covets. The solitary figure in the rough gray outboard, by contrast, is completely engrossed in anticipating a pull on his fishing line. Both men work for the same aircraft manufacturer and have passed 40. The skipper, an executive whose entire vision of himself is tied to the dream of being president, is using his recreational outlet purely as an extension of his occupational efforts. The fisherman, a shipping supervisor with few illusions about fulfilling himself through the job, is using his free tire to pursue a simpler passion as an end in itself.

The skipper would be likely to assume that the fisherman is an underdeveloped dolt. Quite the contrary case can be made by those studying stages of adult life.

The skipper would be likely to assume that the fisherman is an underdeveloped dolt. Quite the contrary case can be made by those studying stages of adult life.

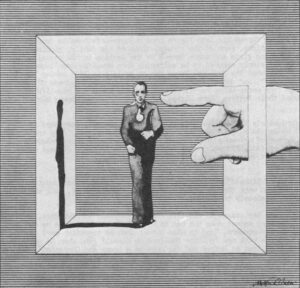

Having observed the lives of both executives and hourly workers, among the four occupational categories included in his study of adult men’s lives, Dr. Daniel J. Levinson of Yale University has formed the impression that adjusting one’s dream downwards around 40 is hardest for the middle management group. “My sense of the workers is that by the time a guy is in his mid-3Os, he knows what the ladder is. Most workers know they are not going to get into management. They have decided their occupation isn’t going to give them much.” Then it’s a question of how to find some other source of satisfaction that would be fulfilling in a deeper sense. “Executive sounds more impressive, but middle-managers are really just a dime a dozen. By the time a middle manager is around 40 he knows his ceiling. It is not something he wants to know. He may try every form of self-delusion, retreat into drinking or hypochondria, cast his wife as a monster, abandon his family — anything to forestall facing incomplete success.

The ideal adjustment would be to accept what satisfaction he can derive from his work, and to invest more of himself in other endeavors for which he had no time when he was obsessed with “making it”: building a home, for instance, or teaching, sports, art, a new area of study, meditation, improved intimacy with his wife and family, deeper friendships. Putting more of oneself into these pursuits can provide the generativity and integrity described by Erik Erikson as essential to overcome stagnation and despair in middle age. And in all likelihood they are far more reliable avenues of fulfillment than can be provided by the fickle American corporation, which is forever straying after young talent.

But there is so much in this adjustment which implies — failure and obsolescence for the executive. He my want to get out, but he often finds it harder to move to a less prestigious job than a skilled worker does. There is more ego involvement and greater humiliation to be faced among his middle-class peers. On top of it all, he has taken on more elaborate financial obligations in the service of setting up the appearance of being on his way to top management.

“They tend to get so locked in to a life structure that may be no good for them, and to internalize the values of that system, that it’s hard to break out,” Dr. Levinson sympathizes. “They believe that they are no good or that there isn’t anything else in life.”

Of the ten executives whose biographies were reconstructed by the Yale team, fewer than half were in the same place on the work ladder two years later. Even those who went up became uneasy, because they now faced the odds that they had reached their highest rung.

I tested this theory on a management consultant who works actively with executive officers of large companies, some of whom inevitably discover the illusory quality of their skills in a recession and turn into what Battalia and Tarrant term “corporate eunuchs.” “One clear stage,” says New York management consultant James Kelly, “is a man (like Ronald Browning) who has been in a large company for twenty years and achieved high levels of status and compensation, but not quite enough to make it to the top echelons of power and prestige. He’s over his head in his business. He is earning too much money for his own good. The corporation is not getting their money’s worth, he knows it, they know it, but to settle for anything less, he would consider demeaning.”

Browning was 42 with twenty years of work and hope invested in a prestige publishing company, but he was never going to be a star. He knew it the day the organization moved him “laterally” (to vice-presidency of another department). “Laterally” is a word every executive recognizes as synonymous with “dead-end.” To the casual dinner guest invited to his formal Tudor house recently purchased in Short Hills, Browning lived up to his $70,000 income. The fact was he had lived his way into obligations such as ~20,000 a year in psychiatry bills for an adopted child. Two years before his father had died. And in the past ten years, since his wife reached her mid-30s, he had enviously watched her blossom as a highly competent social psychologist. She had a wall of books and a lively intellectual life but was not interested in making money and donated most of her services.

The management consultant began getting calls from Browning late at night. “I’d like to buy the XYZ Manufacturing Company and run it myself,” he would announce. And then, false gusto crumbling, “Do you think I’d be good at running that company?”

Kelly knew his client did not want information. He was asking for approval. Approval was something the management consultant could not give, knowing that this very ethical and sensitive man would be miserable in a business which required using call girls to entertain big buyers.

As the months went by, it became clear to Browning that his career demanded either a major change, or resigning himself to a position of increasing, superfluousness on the way to being phased out of his present firm. In painful contrast with his wife’s discovery of occupational excitement at the age of 35 — still new enough to be vital — Browning, after two decades, was dropping fast from devitalization to desperation. He began to phone the management consultant daily:

“You’ve got to get me out of here,” he would plead.

But when Kelly suggested a business he felt suited to his client’s talents, one which would also maintain his financial status, Browning’s answer was always the same: “Too demanding.”

The $70,000-a-year-man began to go through significant personal changes. As the evidence accrued that he would grow no further in his business, he took a week off to study synectics, a creative brainstorming technique, in Cambridge, Mass. This did nothing to reduce his feelings of competition with his psychologist wife. On the contrary, she ridiculed his newfound interest as amateurish. And now Mrs. Browning began to call the management consultant. “Ron’s really a mess,” she reported. “He’s picked up this armchair psychology as something to play with while he’s trying to figure out what to do.”

Browning’s next short-lived enthusiasm was showing dogs. He bought a Bouvier des Flandres and traipsed around the country as if demonstrating a superior product line. When the dog finished a champion, he lost interest and retired it.

The management consultant has two ways of handling middle managers in this kind of mid-life occupational crisis. He may try to convince the executive that the role he is playing is an appropriate one for him, he’s good at it, and to think about being president of his company is not a good aspiration for him. To others, he would say “Get out! You have a lot of money and time. Do something else.” How long it actually takes for a middle manager to make such a change is another story.

“It requires a couple of years, easily,” says Kelly. “The fears are of flopping and stopping. These men are workaholics. They have something they know very well and have worked at. To stop and move to something else is very tough.”

The couple crisis faced by the Brownings is a common secondary complication for a middle manager with an educated wife. Her first opportunity for independent activity after child rearing generally coincides with her husband’s age-40 occupational panic. An analysis of the complicated dynamics involved came out of my discussion with another professional studying phases of adult development. Dr. Roger L. Gould, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at UCLA Medical School, explained:

“The woman who has successfully negotiated this external change would be seeing her husband become more anxious. He would have become more anxious even if she wasn’t building a career, but she will believe that her own individuation is destroying her love object. It may push her back and tend to give her more conflict and pain. They both build up irritations. She is then really angry with him for being in his state of mind, because she reads it as connected with her growth. He, on the other hand, says ‘I want more support. I’m anxious.’ He begins to feel that she made a contract with him to support him all his life, and what on earth is she doing going off on her own life when he is most anxious? At this point, he looks to the home both as a place to get safety as well as a place from which to escape.”

This ambivalence a husband feels about his home seems to peak during his midlife crisis. “It seems a double bind a saint couldn’t beat as a wife,” I observed.

“A saint couldn’t beat it,” Dr. Gould agreed, “because if she was a saint, he would think that she was trapping him.”

A recent H.E.W. report on “Work in America” indicates that some executives would suffer fatal consequences, rather than face a reduced image of themselves: “A general feeling of obsolescence appears to overtake middle managers when they reach their late 30’s. Their careers appear to have reached a plateau, and they realize that life from here on will, be a long and inevitable decline. There is a marked increase in the death rate between the ages of 35 to 40 for employed men, apparently as a result of this ‘midlife crisis’…”

A working class man’s life unfolds differently. But the common middle class view of those differences is erroneous, Dr. Levinson asserts. “That view is they just finish high school, start working, have families, and that’s it. The picture is wrong because a lot of our working class guys went through very important changes between 20 and 35. They didn’t form a life structure right away and just stay in it.”

An electrical engineer studied by the Levinson team, for instance, experienced the Age Thirty Transition as a crisis which profoundly altered his life course in a positive way. Before then, like many hourly workers, he had extended difficulties during his 20s in leaving the family, seriously choosing a life’s work, forming a vision of himself around which to shape the rest of his life, and making a place for himself in the adult world.

Bill (we shall call him) came out of a rough section of Brooklyn, the son of a clerk who was content not to advance in exchange for modest security. When Bill returned home, a combat veteran at the age of 20, he had no notion of what direction to take in life. Fooling around with a buddy one afternoon, he remarked aimlessly, “Hey, why don’t we go to college for a couple of years?” And so, for lack of anything better to do, they took up the study of electrical work at a state agricultural college.

He was married in his senior year, again, Bill admits, without giving it much thought. He did manage to get away from Brooklyn, despite his mother’s protests, but then substituted for his doting, mother an even more indulgent mother-in-law, who came to live with him and his wife. The next six years until the age of 29, Bill spent in a meaningless occupational drift. Making, no use of his college training, his work boiled down to being a telephone operator. His wife worked too. They argued about money. Children were financially out of the question. They described their marriage as tolerable, but refused to look beneath its service aspects. He liked being “taken care of” by his mother-in-law and a supportive father. Yes, he had built a life structure — job, home, and family — but it was a leaky ship. On all fronts Bill was floating. And by anyone’s assessment including his own, content to remain so.

At the age of 29 his support system fell apart. Both his father and his mother-in-law died within the year. Forced either to sink or to become the man in the family, Bill tore up the life structure he had spent his 20s building. He reached out for a new life in Florida. For the first time he took a job (in data processing) that put his college skills to use. Aimlessness gave way to goals and ambitions. He began to value his contribution as a liaison between the workers and managers, to enthusiastically set his sights on becoming a supervisor. It had taken Bill until the age of 32 to think of himself as a man with a career, heading a family with a future.

One of the greatest handicaps an hourly worker faces in his 30s is lack of a mentor, according, to Levinson. A mentor is an older adult who supports a young man’s vision of himself and helps him to put it into effect in the real world. The most successful men generally have mentors, but people with the time and inclination to play such a role are scarce in plants and factories. A foreman is not a mentor any more than a drill sergeant is father figure.

Judging by my own interviews, it seems common for working class men to tally up the occupational rewards they can expect earlier and more realistically than driven corporation men, and to find other avenues to pursue excellence and play out competitiveness. (For one thing, it makes me infinitely more tolerant of compulsive fly-tiers, demolition derbyists, and obsessive mountain climbers and even — after trying it myself — of sport parachutists.)

Terry Bennett, a bar owner in Queens, is far less invested in his old career visions than is corporation manager Ron Browning at the same age of 42. This is not explained simply by the bar owner’s more limited education and social level. Terry Bennett planned to be a millionaire at 30 too. When he found himself “a lotta dollars short,” he settled into a limited disappointing occupational life, battled and overcame a serious drinking problem, and began building on dreams that weren’t dependent on his work. Private schools for his children was one (his grandfather emigrated from Ireland with an “X” on his birth certificate), and building a second home in the Catskill Mountains. To enjoy being his own contractor, he often takes three — and four-day weekends. (The Ron Brownings of corporate life, on the rare occasions when their secretaries force them to take time off to become re-civilized, do it only to recharge their batteries for the return to work.)

“I’m not a sheep,” says Bennett the bar owner, “but I know my capabilities and my level in life and I have no great ambitions now. I’m not an old man but I know where I’m at. I’m not a dreamer I’m not gonna be something I’m not. That’s very important.”

Perhaps the greatest anguish awaits the hourly worker who harbors the same dreams, and for just as long, as the middle manager who looks for all his fulfillments in work.

The 39-year-old foreman of the shipping department at a Boston newspaper came through as such a man, in a portrait sensitively drawn by Thomas J. Cottle in “A Middle American Marriage” (Harper’s Magazine). A worker’s boss, Ted Graziano had been at the age of 30 totally invested in his job as a source of pride, challenge, excitement, economic and social advancement and — perhaps most precarious-as an affirmation of his manhood. He wouldn’t consider allowing his wife to work, and then comforted himself by complaining about his solitary burden as breadwinner. “Many times I’ve thought about what it would be like having your wife and children working while you sat around the house, sick or tired or something…” he confessed apprehensively. “That may be the worst death of all. When women work it’s a fill-in.”

On the brink of mid-life, Ted’s work had not changed, would not change, and had become just another job. A cheat. A badge of shame. An inexorable daily death for which humiliation he cannot punish his bosses, and so he lashes out at his wife and children — “four ungrateful human beings” for whom his sweat makes it possible to live with a little dignity. He complains of not having a soul to talk to in his house.

The meagerness of talk between husbands and wives in blue-collar marriages has been documented by Mirra Komarovsky, but as we see in this case, it is compounded by the wife being a shut-in and the husband having little to crow about when he comes home. With a writer in his kitchen as a “jury,” Ted Graziano could let his bitterness boil over:

“You think it’s easy for a man every day to look around at his life and be reminded of what a pitiful failure he is, and always will be? That’s the death part, Ellie [his wife]. And that’s the part, reporter, you better write about if you want to understand people like us. It’s seeing every day of your life what you got and knowing, knowing like your own name, that it ain’t never gonna get better. That’s why a man drinks. In this country, there ain’t no one who fails and holds his head up. No one likes a loser. That’s why the rich can’t stand us.”

He berates his wife for her faith that things will get better. Her misplaced faith is further painful evidence of the failure he feels:

“I see the future that you and your mother and all those idiots at church pray to God to take care of for you. I see that future. I’m already 70 years old and still working, still lifting Sunday papers … You’re praying, and I’m working to have enough money to buy a place, and a way to get rid of my body which, if you’d really care to know, was dead a long, long time ago.”

Ted’s view of the future on the rim of mid-life incorporates in a few words all the agonies of that time warp; the sense of having aged decades overnight, of having to face the truth that there is no one to take care of you, the lost illusions of success, the reality of sweating out work and insignificant bonuses and going nowhere, finally, except under an expensive tombstone.

But after blaming his wife as the depriving figure who treats him as a little boy-a most common transference for men in mid-life crisis — Ted gets down to the real culprits. The rich. The successes. The lucky few who scale to the top of the corporate pyramid in America, Inc., where autonomy and dignity are possible. And here, Ted’s insight is sharp into the developmental advantages enjoyed by those who think ahead:

“The rich work to make their lives work out. They think in enormous blocks of time. They’re moving in decades.”

It would be hard to convince a Ted Graziano that a $70,000 a year man like Ron Browning can suffer a similar sense of worthlessness and despair in mid-life. It is less a matter of class or career choice than focus. Anyone who narrows his focus in his Ms to a single channel — fulfillment through the lob — is in for rough sailing on the open seas of the 40s.

Where Ted is correct is in envying those who perceive their lives in large blocks, who build to reinforce the next decade rather than living by accident. Although this is an easier trick for men who are economically secure, it is by no means limited to them nor necessarily practiced.

And therein lies the contribution we, can hope for from current studies of adult development. The life cycle of each individual could be navigated with far more wisdom if we had sore idea of where we are going, when to expect rough seas, and how to design our own harbors.

Received in New York on December 21, 1973

©1973 Gail Sheehy

Gail Sheehy is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from New York Magazine. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Sheehy, New York Magazine, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.