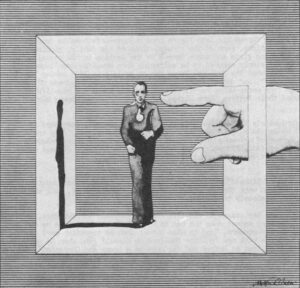

No one knows why the master is afraid to close his eyes. Why, at 43, called out on the balcony of his life’s accomplishment to be cheered by the crowd, he has trouble simply keeping his balance. The supports of success are not holding.

It began about four years ago. He ignored it at first, and took on more work. Let us imagine the master is an architect and give him the name Aaron Coleman Webb. To protect his personal privacy the details of his professional life have been altered to a precise equivalent; the description and quote about his inner life are all exact. So, in his 39th year, we will say, he threw himself into a new publication, another teaching position, grander commissions in more prestigious cities. At 40, he was selected as resident architect of one of the world’s great fine-arts academies. Last year, it was an invitation by a foreign government to design its new parliament building. But no matter where he shifted his weight, there was a giving way of struts, braces and trusses.

“The most influential [architectural planner] of our time,” pronounces the leading critic in his field. He read the commentary. And then he closed his eyes and let it overtake him, a sense of internal collapse so powerful that he was no longer willing to prevent it.

“I have always used my work as a substitute for solving problems in my life,” he can now admit. “It began when I married. I packed my life with activity in order to avoid major personal decisions. What I do is give up autonomy by creating a high demand situation, so that I must always jump from project to project, never really allowing time to think about what I’m doing it all for. Since I turned 40, it’s become clearer to me that the reason I do this — ” he hesitates a beat ” — is I really haven’t wanted to scrutinize what my life is all about. Just the idea of stopping to investigate is an indication that something has changed.”

It is a change that has recently been given a name: Mid-Life Crisis. What it’s all about is the passage from youth into middle age. Anyone who has walked that treacherous footbridge between the ages of 37 and 43 should recognize some of the sensations the architect describes.

We are not talking about cracks in the physical shell, the hinges that begin to stick on the tennis court, the creases of flesh and silvering of fun and imagined malignancies that coincide with the sudden hospitalizations of friends. These play their part, but only as an accompaniment to the deeper sense of slippage inside.

It would be easy for the architect Aaron Coleman Webb to continue performing for others as if nothing was happening, to withdraw from his wife or divorce her, to fool himself. From the outside, his support system could not be sturdier. His dream was taking shape as early as kindergarten. He would be a builder, and that would bring him power. His mentor in design school endorsed that dream, but when the mentor tried to confine it, Aaron gave him up. Plunging ahead alone, he converted his dream into a goal, which grew, to gigantic proportions by the time he was 35.

“There was a shift then, and my goal became a very specific one — to move the firm to the position where it would be the best of its kind in the world,” he recalls. “I really wanted to achieve a kind of professional mastery which would make me immune to anybody’s control, to get into a leverage position of such dimension that no one would be able to criticize me. And to a large extent, I achieved that.”

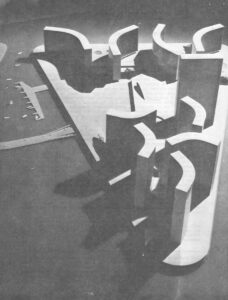

The metropolis where he was born, in back of a grocery store, is studded with ornaments of his talent. Up and down these streets is a living mosaic of luxury convention hotels, witty renovations of fishy-eyed storefronts, airport terminals that seem to levitate in the ionosphere, all bearing witness to the twenty-year evolution of his genius. People point to them from buses and taxis. “That’s an Aaron Coleman Webb building,” they can say with certainty, for his stroke is unmistakable. So unique are his concepts, in fact, that dozens of architectural designers around the world have built on them full-scale careers of their own.

The metropolis where he was born, in back of a grocery store, is studded with ornaments of his talent. Up and down these streets is a living mosaic of luxury convention hotels, witty renovations of fishy-eyed storefronts, airport terminals that seem to levitate in the ionosphere, all bearing witness to the twenty-year evolution of his genius. People point to them from buses and taxis. “That’s an Aaron Coleman Webb building,” they can say with certainty, for his stroke is unmistakable. So unique are his concepts, in fact, that dozens of architectural designers around the world have built on them full-scale careers of their own.

By external measurements, then, there is a strong continuity to Aaron’s life. Many men spend years between two chairs, not quite certain if they are innovators or administrators, original researchers or teachers, lawyers or politicians, politicians or hacks. Aaron is clearly an architectural designer of a stamp as certain as the hallmark on Tiffany sterling. It is a center around which his life could be organized, and has been since the age of five.

Personally the chinks do no show. Short and feisty with a vigorous, ungrayed beard, Aaron seems to go through life’s growth processes as naturally as grass. He spreads around his exuberance for rock starts and cheap Greek restaurants as easily as for “high art.” While other only watch, he learns from everything. He wears jean and vegetable garden ties and, as a matter of habit, a playful smile. His wife, in handsome contrast, is ethereal as a fern. About displaying her own unique artistic imagination she is ver private, in fact recessive. He cooks. She cooks. They migrate on weekends to an old-shoe country house. In place of children they have a worldwide network of friends and associates.

These people see Aaron as a warm man; free of spirit and undefended by the petty weapons used by those less secure in life’s marketplace. He interacts easily with the younger men he teaches. “Everything in my life has happened perfectly,” he tells them. Never dressy, never pretentious, he appears to be a man completely comfortable with himself. And why not? He can go to sleep at night with a view from his high-rise of a once-decrepit city profile made younger and more beautiful by his own hand. It would be a temptation for such a man to regard himself as a god.

But closing his eyes, in the instant between realms when outer achievements must be let go, Aaron Coleman Webb is alone with that sense of internal collapse. Many mean and women who biographies I have collected experience the same sensations at this point in the life cycle. Although they can say at 43 or 44, “I really went through hell for a few years and I’m just coming out of it,” their capacity to describe what it felt like is often limited. They don’t dare walk backwards over the gaping crevasse. People right in the middle of the mid-life transition my be so panicky, the only descriptions they can summon are of “living in a state of suspended animations” or “I sometimes wonder in the mornings if life is worth getting up for.” To be any more introspective is dangerous. Other people are blockers. Whiz kid business executives and puppeteering hostesses, for example, may try to hold back this stage as long as possible. They don’t have time for a mid-life crisis. They’re giving dinner parties or starting a business that year. They consume themselves with externals for the very reason that they fear dipping into what might be the chaos inside. The catch is issues not tackled in one period ten to come up in the next one with an extra wallop.

But closing his eyes, in the instant between realms when outer achievements must be let go, Aaron Coleman Webb is alone with that sense of internal collapse. Many mean and women who biographies I have collected experience the same sensations at this point in the life cycle. Although they can say at 43 or 44, “I really went through hell for a few years and I’m just coming out of it,” their capacity to describe what it felt like is often limited. They don’t dare walk backwards over the gaping crevasse. People right in the middle of the mid-life transition my be so panicky, the only descriptions they can summon are of “living in a state of suspended animations” or “I sometimes wonder in the mornings if life is worth getting up for.” To be any more introspective is dangerous. Other people are blockers. Whiz kid business executives and puppeteering hostesses, for example, may try to hold back this stage as long as possible. They don’t have time for a mid-life crisis. They’re giving dinner parties or starting a business that year. They consume themselves with externals for the very reason that they fear dipping into what might be the chaos inside. The catch is issues not tackled in one period ten to come up in the next one with an extra wallop.

I have chosen to tell you about Aaron for two reasons. It is rare to find someone so well able to articulate and so willing to ventilate the feelings that bring on the emotional vertigo of this period. Even more to the point, judging by emerging theories of adult development, Aaron is likely to regain his balance. (His name and profession have been disguised to protect his privacy.)

The architect won’t let himself run away into work anymore. He isn’t taking the easy, dead-end escape routes with booze, feel-good pills or the moist young gidget who mythically guarantees to make a middle-ages man feel 20 again. Aaron doesn’t have all the answers yet, but he is no longer afraid to ask the right questions:

“What I’ve discovered over the last year is how much of what is inadmissible to myself I have suppressed. Feelings that I’ve always refused to admit are surfacing in a way that I am no longer willing to prevent. I’m willing to accept the responsibility for what I really feel. I don’t have to pretend those feelings don’t exist in order to accommodate a model of what I should be. I’m really shocked now at the range and the quality of those feelings — feelings of fear, of envy, of greed, of competition. All these so-called bad feelings are really rising where I can see them and feel them. I’m amazed at the incredible energy we all spend suppressing them and not admitting pain.”

Aaron’s words encapsulate the condition of being in mid-life crisis. It is not by coincidence that I was taking down his words on the East Coast, they were being echoes across the continent in a talk on mid-life crisis by Roger L. Gould, an associate professor of psychiatry at UCLA who has been studying the stages of adult development. Dr. Gould focuses on the inner shifts of experience from one stage to the next.

As he sees it, the early to mid-40s is when we must open up, loosen the narrow, stereotyped models of ourselves and take in all our “so-called bad feelings” and submerged parts. It is also the time when each of us must finally believe what we suspected all along: We stand-alone. We are the only ones with our own set of thoughts and bundle of feelings. Another person can taste them, through conversation or shared experience, but no other person can ever really digest them. Not a wife or husband, though they may be able to finish our sentences; not a mentor or boss, though they may be of good will in working out their own ambitions through us; not even our parents.

In childhood we all identify with our parents. And from the identifications we carry along the deepest layer of imaginary protection. It is this internalized “protection” that gives us a sense of insulation from being burned by life, from being bullied by others, and even into mid-life from coming face to face with our own absolute separateness. But it is an illusion.

Identification is a process by which a person ascribes to himself the qualities or characteristics of another person, originally one’s parents or parent substitutes. But the illusion of inner companionship, kept alive by what psychologists call an “incomplete identification,” only soothes us against the idea of being alone. It does nothing to actually protect us form being separate. In fact, by hanging on to this illusionary protection, we hold back something far richer. What is to be gained by giving it up is no less than the full authority to be our own freely authentic selves.

This fullness or our being is released only when we are ready to face the final truth of the mid-life period. There is no protective “other” with you inside the dark room of your mind. There is no one who can keep you safe. There is no one to take care of you, no one who won’t ever leave you alone.

So staggering a loss is this to accept, the blame is often displaced on the next closest person — the mate. Dissatisfaction, discord, destructiveness and divorce reach their peak in the marriages of the early 40s (among those who have not already divorced). The dialogue of the argument has a thousand and one variations, but the essence of the conflict usually comes down to the same thing. Each person experiences the other as the demon and him or herself as the victim.

Separation can be exercised by either mate at any time. They can stop hearing, touching, talking, caring or even being there. This hovering threat makes each of us feel controlled by, and at the mercy of, the other.

When we first hike off to a friend or an analyst or a marriage counselor, it is like going to court, each of us wants a judgment that the other is fully culpable as the demon. We both would like a decree from some omnipotent third party that will break the power of the other’s grip on us. Each of us would like to prove personal sovereignty and never be a needful one again.

This argument is replayed throughout marriage. But why does it crescendo in the 40s and so often cause that clash of cymbals we might call the Predictable Mid-Life Couple Crisis?

At 43, Aaron’s wife finds herself using the word “separation.” Not the kind that needs a lawyer, but a far more difficult personal task of separating herself from Aaron’s dream. By “dream” I mean that personal vision which commonly takes shape in the 20s and generates energy, aliveness and hope.

Once upon a time, before she had the confidence to state it, Nicole had her own artistic expectations. And her own gifts of juggling color and shape into designs for interiors that took her teachers’ breath away. There is that moment, stepping out of college, when a woman has the chance to elope with her own talents before she loses her nerve. But Aaron had stepped out of the same school two years before her, and Aaron was so much surer footed. He was already making strides toward building an architectural firm. Nicole took what seemed at the time a smaller, easier step, one that until very recently our culture has fully endorsed. She piggybacked her dream.

For fifteen years she has lived off the vicarious fruits of Aaron’s unfolding talent. But those fruits were the only ones she got. A few years ago they began to turn sour. She is angry — but no angrier than the millions of women who live through their men. Coming into their 40s, they find themselves no longer able to be carriers of the dream which formerly made them feel safe, because now they resent it as belonging exclusively to their husbands.

What happens when the docile wife and dutiful hostess, on whom a husband has counted for nearly two decades to be the absorber of anxiety, begins to feel her own oats in her 40s? She is ready to strike out, get a job, go back to school, kick up her heels; just as he is drawing back, gasping for breath, feeling futile about where he has been and uncertain about simply keeping his balance on this job and in bed. How is he likely to react to her sudden surge toward independence?

Imagine having a parent die when you are flat on your back with an undiagnosed disease. Imagine the howl of pain, the panic, the outrage, and the emotional refusal to accept such a desertion when you yourself are in such a state of helpless uncertainty and desperately in need of reassurance. That is his side.

What of her side? “You must build a man’s ego” is the time-honored advice. Wives obediently pour out a heaping dose of mothering, and then feel betrayed when it backfires. And it will almost certainly backfire. Exactly what a man can no longer accept as he attempts the mid-life transition into full adulthood is a wife acting as Mother. The same wifely qualities he idealized in the marriage of his 20s, when they benevolently provided for his nourishment, he now rejects as maliciously designed for his entrapment. This switch throws a woman into a double bind. We can now explain it as a predictable switch.

But where, in all the reams of advice to wives of middle-aged men, is a word about how to build her ego?

The woman who is nervously trying to negotiate her own next developmental step must also, at this stage, take back the parental authority assigned to her spouse. Suppose she does make some successful external changes? Suppose, for instance, she pulls together her tattered self-confidence, runs for president of the League of Women Voters, and wins? She then sees her husband becoming more anxious. He would have become more anxious at this stage in any case, but a formerly dormant wife is likely to believe the cause is herself. Her own individuation is destroying her love object. This idea pushes her back. Fear, guild, conflict creep into the picture. And then anger.

She is thinking: Why can’t he hold together like a good husband, so that I can go out and grow without feeling so guilty?

While he is thinking: What in hell is she doing running off in the other direction when I’m falling apart?

In his most anxious periods, a man looks to his home as a place to get safety and a trap to escape. He sees it both ways.

A saint could no beat this ambivalence. For if his wife reacts as a saint, he will see her as trying to seduce him back into the trap. Ergo the ritual complaint of the middle-aged man: My wife doesn’t understand me.

Fortunately, although the possible consequences disturb him, Aaron is able to see that Nicole’s physical separation from him and his dream is essential if she is to find her own fulfillment. It is half the step toward invigorating a marriage which might otherwise stagnate, if not fall apart.

“She really has to acknowledge her own feelings, her own reality and competition, and act them out in a way that’s independent from my dream,” Aaron can explain. “That’s what Nicole is trying to do right now. I try to be supportive to her, but the issue of supportiveness becomes a very involved parental one.”

The other step is his. The key word is “parental.”

For the moment, I shifted the emphasis from Nicole, from the center of knot. I talked with Aaron about his range of feelings for the many young men he has nurtured and dispatched from his firm to distant successes of their own. Was he always “supportive” as an artistic parent, or sometimes detached and dictatorial, depending on how much fealty a former student showed him?

“I do now that part of my parental quality can be punishing,” Aaron offered. “And for some people it has been, although for a long period in my life I wouldn’t admit that. I would want to be the good father.”

“But, with control?” I suggested.

“A lot of control and a lot of punishment.”

“Have you been punishing Nicole?”

“Yuh,” he said hesitantly, “I think so.”

“Is withdrawal a form of punishment?”

“One form.” He paused; this was a painful dredging operation. “Withdrawal and criticism. Whether I really want her dependent on me as a kind of — ” He stopped short of the word ‘father’ and finished lamely. “It’s so complicated.”

This complicated lock is part of the mid-life crisis for many couples. Aaron must give up a role he has formerly enjoyed that of Nicole’s surrogate father, just, as she must relinquish the dependency on him, which she now so strongly resents. But in unbolting that door, she will lose all her illusions of absolute safety. And he will have the frightening opportunity to admit what he is now feeling inside. It is a confession that goes to the heard of his image of himself both as celebrated creator and strong husband:

“It’s very hard to give up your personality successes. The manipulative things that have worked for you, that are approved by others and enabled you to achieve your goals. But they have to be given up if your sense of them has been false. I don’t want to screen out the bad again so I can be made a ‘good’ person.”

The “bad feelings” that Aaron described a while back — the fear, envy, greed and competition — have pushed up from earlier stages and come partly unstuck from their source, the internalized parents already described. But the source is a two-faced image. Besides being the benevolent “protector,” it has the face of a menacing dictator. Think of Janus, the ancient god of gates and doors and hence of all beginnings. His two bearded profiles, back to back and looking in opposite directions, represent two sides of the same household door. But is inside the door safety or entrapment? Is outside the door freedom or danger? The impassive faces of Janus reveal no answer.

This is what makes the bad feelings so unsettling and sinister when in mid-life they come loose from their source. Now, like unvarnished chips off the warped, archaic totem pole of childhood, they are free-floating. What better person to project these inadmissible feelings upon, for the time being, than the one who is closest to you? Your husband or wife.

These feelings are not perceived as some abstract idea. They are a real and menacing escort, a dictator within. The very demon that most marital arguments are all about.

When you set about the task of mid-life housecleaning, as both Aaron and Nicole are doing, whether the demon is inside or outside becomes a crucial question, frankly terrifying to explore. If it is within you, what to do? Run away or polish it up and take it in? If you have chosen a mate to act out the inner dictator, or jockeyed one into the position of doing so, what then? Painstakingly give up your collusive “manipulations”? Or take bitterness as your shield and divorce?

The consequences are potentially life shattering — life-renewing.

The essence of mid-life crisis, then, comes down to two fundamental stresses, which impinge on us at the time we are feeling most vulnerable. By the early to mid-40s, we have already lived out the period in which we could convert the dreams into a goal. Having reached that goal, or fallen short, or never having converted the dream at all, each of us now asks, Is there nothing more?

The other stress comes with a reawakening of unresolved problems that are tooted, if not buried, in earlier stages of our development. We must give up the last of the protective illusions brought along from childhood. At the same time, the tempo of life shifts without warning. Now there is a time squeeze, a new sense of urgency and a very real deadline: the awareness of one’s own personal death. It forces all of us to realize we will not do, or be, all that we had hoped for.

The transition into mid-life need not be full-blown crisis. But failure to resolve the real issues of this most difficult period in becoming an adult can be a crisis. A number of psychiatrists and social psychologists have connected this failure to the high rates of depression, suicide, alcoholism, infantilism and the leap in divorces that occur in this period. Mid-life crisis has also been used as an explanation for why many highly creative and industrious people burn out by the mid-30s. Even more dramatic is the evidence that they can die from it.

Following the lead of psychoanalyst Erik H. Erikson, students of adult development see life as a series of steps. People pass from one level to another in observable sequence. Erikson does not suggest that development is a series of crises. He claims only that psychosocial development proceeds by critical steps,”‘critical’ being a characteristic of turning points, of moments of decision between progression and regression, integrations and retardation.”

Development takes place on a daily basis. A series of microscopic experiences require us to remodel ourselves continually, in search of a better fit between the inner imperatives which drive us — love, sex, safety, autonomy, accomplishment, integrity, etc. — and the outer structures which enclose us — marriage, occupations and memberships in society. Career success or a marriage of long standing are not necessarily indicators of development. In fact, they may lock us up in ways that can impede genuine inner growth.

It is most useful, then, to think of all persons as constantly refining their own view of the world and their sense of self within that world. We seek external structures such as jobs, love partners subgroups of friends and social organizations that fit us for a time and endorse our new sense of self and world view. But in some symmetry with our internal changes, these external structures have to be constantly remodeled or exchanged for other such structures.

In this sense, people are structures. Parents, spouses, bosses, mentors, friends and associates help to erect and furnish that edifice into which we try to fit. They also crowd us. We try to remodel our partners or we outgrow them. In the same way we may expand beyond an occupations fit. Always, the individual is trying to include more and more of his essential parts. Some of these parts will not be attractive. But only when they are dredged up and stripped of their childhood identifications with parents can they be worked on and remodeled into a more benign form. It is in this way that each person’s unique potential can unfold.

We do not “solve” with one step our problems of separation from the inner dictator; by jumping out of the parental home and into marriage, for instance. Nor do we “achieve” autonomy by converting our dreams into concrete goals, even when we attain those goals. Most of us are spurred on by belief that when a person is pronounced fully in charge of his own enterprise, he will be fully adult and in command of himself. But with Aaron as our witness, that only brings the individual to another step.

At this point, Aaron is sitting in a drafting room cluttered with rendering, blueprints and models. Staring at his award-winning designs from this new perspective, he sees in them a refinement of those very manipulative techniques he will now have to give up. The workshop is the hub of an architectural planning center, which he and his partner have been building for almost twenty years. Aaron is its public face, the celebrity. His partner, an intensely private architect who has infused the center with his own quiet imagination, is an unknown quantity to the general public. Their alliance under one roof has become an uneasy fit.

The larger issue, which incorporates all these parts, is: Where do you go from the op? Aaron has done it all. He has built his own creative dominion and put it on the map as the finest of its kind in the world. A sovereign state with no wilderness left unexplored. Cover it with glass and it would be a museum. Standing on the topmost pinnacle of his dream, then, Aaron is terrified of stagnation. He talks about finding a way to “phase out a little.” At the same time, he slips in the phrase “hold on to a piece of control.” He is not quite ready to come down with both feet on a decision to change his entire life structure. To give up what he ahs complete dextrally, in order to let himself fully experience what is coming up from inside, would point the way. The way to a more intimate footing in his marriage, a deeper vein of creativity and a truer glide path toward personal fulfillment in his work. The way to fall up from the top.

Toward the end of this interview, he grapples with the question. The great man’s voice funnels down to a hush. He picks up a pencil and puts it down. No props.

“I don’t know what I want to do. It’s a time of confusion for me, great personal confusion. What I really have to learn for myself are the feelings of passivity, dependence, weakness, frailty, all the things that are abhorrent to me of the intellectual level. As a counterweight to that, I must permit myself to acknowledge my own aggression, my punishing quality — all the rest of that. I can’t pretend anymore that duality of roles does not exist.”

The architect has his new work cut out for him.

Received in New York on April 12, 1974.

©1974 Gail Sheehy

Gail Sheehy is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from New York Magazine. This article is adapted from chapter of a book in progress and appears simultaneously in the April 29th issue of New York. It may be republished with credit to Ms. Sheehy, to the Alicia Patterson Foundation, and New York Magazine. The following copyright notice must appear: “Copyright ©1974 by Gail Sheehy. Reprinted by permission of the author.”