The Mexican military received nearly a dozen complaints about cartel activity in the region where 43 students were abducted in September 2014, emails hacked from the country’s defense ministry reveal, but the armed forces apparently did little to tackle organized crime in the area.

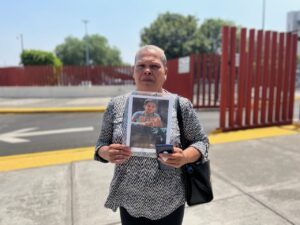

The students’ kidnapping and disappearance, which took place in the city of Iguala in Guerrero state, was one of the most horrific and high-profile human rights abuses in Mexico’s recent history, and remains unsolved despite years of protests and a relentless pursuit of justice by the students’ parents.

In the eight months before the students were attacked, citizens of Iguala and surrounding towns wrote at least 10 emails to the 27th infantry battalion denouncing the presence of criminal groups and the apparent collusion of local authorities. Some included photos of alleged members of the Guerreros Unidos cartel, which is accused of orchestrating the students’ disappearance.

“Armed men have returned to patrol the town,” wrote one person, referring to a nearby hamlet a month before the disappearance of the students. “They meet next to the town cemetery, they also meet in the square of Cocula, Guerrero, without being bothered by ministerial, state or municipal [police].”

Taken together, the emails capture the fear and frustration experienced by the region’s citizens due to the presence of violent criminal groups, as well as the apparent collusion between organized crime and local authorities, and suggest that local military personnel had clear knowledge of what was going on.

“There were all these citizen complaints about heightened levels of criminal activity right there, in that part of Guerrero, in the weeks and months before the boys were kidnapped, and clearly nothing was done,” said Kate Doyle, a senior analyst at the National Security Archive in Washington DC. “The messages are chilling because we know what happens next.”

The complaints are part of the more than 4m emails and documents leaked in September last year by the hacker group calling itself Guacamaya. The hack of more than six terabytes of information is one of the most serious breaches ever of Mexican national security.

The government has not denied the authenticity of the emails, although President Andrés Manuel López Obrador recently emphasized that the information is “illegal, because information from any government agency cannot be extracted or hacked”.

The emails reviewed by the Guardian support the findings of the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI), which has spent eight years investigating the students’ disappearance and repeatedly highlighted the extensive knowledge that military personnel in the area had of criminal activity, including during the night of 26 September 2014.

“They monitored the narcos and organized crime,” said Carlos Beristain, a member of the GIEI. The night of the attack, however, “the decision was to do nothing”.

The night they vanished, the students from the Ayotzinapa rural teachers’ college had commandeered a number of buses to take to a protest, a largely tolerated tradition. But in Iguala, they were attacked by local police officers working for Guerreros Unidos, who forced dozens of students off the buses and drove them away into the night. The remains of just three students have been identified.

The independent investigators have alleged that the military had detailed knowledge of criminal activity and collusion between the cartel and police. They also had real-time knowledge of the attack as it unfolded.

It is not clear if the complaints that arrived in the inbox of the 27 Infantry Battalion in Iguala were investigated or verified by the military. But, according to Beristain, the army’s actions in the months prior to the attack on the students were limited.

“They were active in different places, they participated, they went to visit a place where there were shootings, we know that they detained people in other places,” Beristain said. “What we [also] know is that there is no effort to take apart the criminal structure in Iguala.”

In the period when the emails were sent, several criminal groups were operating in and around Iguala: among them was Guerreros Unidos, which oversaw an operation moving heroin between Guerrero and Chicago. Text messages between members of the cartel intercepted by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) at the time suggest there was collusion between the cartel and members of the military, according to the investigators.

While the emails appear to be sent to a general complaints inbox, one of them, sent in May 2014, is addressed specifically “for the attention of my Colonel José Rodríguez Pérez” who was in command of the 27th Battalion at the time and who was arrested last year for his apparent involvement in the disappearance of the students. Rodríguez has denied the allegations.

That email was sent by a representative of a company which owns a mine near Iguala. A subsequent email from the same person contains a document detailing how an armed group “has been taking control of the town of Atzcala”, in the municipality of Cocula, where the remains of two students were found.

“Last Saturday, May 24, its members fired their weapons during the night simulating a confrontation with a rival group and the next day they gathered the residents of Atzcala to ask for their collaboration and their weapons,” the document reads.

According to the document, the members of the group carried weapons including AK-47 and AR-15 type rifles.

In another instance, a citizen wrote in July 2014 about alleged cartel lookouts operating in Iguala, although he does not detail which criminal group they belong to.

“I had already called the number for anonymous complaints, about these guys who are lookouts,” the person wrote. “Now they are intimidating local residents and merchants offering protection in exchange for money.”

The complainant also suggests complicity between the local authorities and the alleged lookouts: “I have seen them talking with transit and municipal police, even with civil protection firefighters.”

Another series of emails sent in June 2014 describe the activities of the Guerreros Unidos cartel in Iguala and nearby towns, and even includes photos of various individuals alleged to be involved with the group, some holding high-caliber rifles.

“They are the chiefs of Huitzuco, Iguala and Apaxtla,” says an email with the subject “Guerreros Unidos”, referring to several towns in the area. “There are two who warn about inspections,” they write. “One is nicknamed Skinny, he was an army officer and now he works for the ministerial [police]”.

Another, from the same person, describes a location “above the highway” where “they have kidnapped people”. The person goes on to say that in the Loma del Zapatero neighborhood in Iguala “a white Tacoma drives around” adding “they tortured us in February and at the Ahuehuepan checkpoint they took our cars and there are women in uniforms.”

In another email from April 2014, which was previously published by the National Security Archive, a subject recounts how members of a criminal group operated “with impunity with their AK-47 weapons … in front of the municipal police”.

The complaint, which refers to the towns of Apaxtla, Teloloapan, Cuetzala and Cocula, says that although impunity has decreased, the criminal group continues to operate: “It is not a drug trafficking cartel, but rather a bunch of assailants, pickpockets and kidnappers, who set up their checkpoints to kidnap people.”

The email ends by detailing the place and date where a subject known as “El Pez” could be captured, a nickname that corresponds to Johnny Hurtado Olascoaga, one of the leaders of the criminal group La Familia Michoacana.

“I am asking you to please carry out an effective ground-air operation,” writes the complainant. “And if you don’t, we can’t trust you anymore either.”

Last month, members of the military, the National Guard and agents of the Guerrero attorney general’s office finally carried out an operation to capture El Pez and his brother, known as “El Fresa”. Both escaped and are still at large.

A detailed set of questions sent to the defense ministry went unanswered.