September 5, 1969

BRACKNELL, Berks – For a famous place, Bracknell new town is strikingly ordinary. The main sights for the 2000 visitors who toured through last year were shoppers, children playing, and hundreds on hundreds of neat houses with flower gardens in front.

The phrase new city or new town has come to have a certain cachet. It brings to mind sharp-angled architecture rising from a flat horizon. A new city is a fresh start, without slums, or old people, or people out of work, or people the wrong color – all errors of the past not to be repeated. Living the properly ordered life, new city citizens will approach ever closer to redemption.

And nowadays, the phrase is often a pitch-man’s come-on, a slogan for the promoter with too many houses to unload.

Bracknell is none of these.

It is a new town that actually exists, one of eight surrounding London and 27 in Britain. Some 33,600 people live there now, 30 miles west of London, and 60,000 will in a few years. Fifteen years ago it was just drawings on paper.

Design has been both painstaking and good in Bracknell, but it is without genius or grand artifice. The waterjet rising hundreds of feet from the lake next to the sales office, a mark of style in American new cities, is missing. In its place are a convenient layout of streets, cheap, comfortable housing, and lots of free parking.

Some of the problems that have plagued cities for decades have been solved. Every one of the 160,000-odd units built in new towns has a toilet and a bath, for example, although a quarter of urban England does not.

But Bracknell and the other new towns face some problems even more acutely than older cities. Under discussion this summer throughout the country are these:

How can people be convinced there is some point to local government, that it is worth their efforts?

How can local government be made competent to do its increasingly complicated and difficult job?

New Towns’ Beginning

British new towns (it remains a town even when its population hits a quarter million) are the product of an idea. Just before the turn of the century, a man named Ebenezer Howard read and was much taken with “Looking Backward,” Edward Bellamy’s view of an American utopia. Howard wrote a book called “Garden Cities of Tomorrow.”

The book describes “how higher wages are compatible with reduced rents and rates (taxes); how abundant opportunities for employment and bright prospects for advancement may be secured for all; how capital may be attracted and wealth created; how the most admirable sanitary conditions may be ensured; how beautiful homes and gardens may be seen on every hand; how the bounds of freedom may be widened, and yet all the best results of concert and cooperation gathered in by a happy people.”

His design was for a new city of some 30,000 persons in a rural setting. All would live in cottages with gardens, built on commonly owned land. The factories and the greenbelt would be only minutes’ walk from every home. Howard also supplied detailed layouts and plans as well as plans for social organization.

He took part in building two garden cities, Letchworth and Welwyn. They started with too little money, but survived to become, slowly, successes. They were not widely imitated, however, a source of discontent to the ardent backers of the idea, organized as the Town and Country Planning Association.

They persevered, writing, studying, arguing and urging when few others were actively concerned with improvement of city life. During the war, when plans were made for rebuilding London and housing the expected growth in population, the new town backers were ready. In 1946 Parliament passed the New Towns Act.

A new town was seen as an alternative to the city, particularly London. It would provide the cottages, factories and shops, all interlaced with parks and trees and surrounded by healthful fields. At the same time it would help ease population pressure on London and get some new housing built.

A development corporation, run by an appointed nine-member board, was to see to the design and construction of each new town. After choosing the place, buying the land (by condemnation if necessary) and drawing designs, building would start, using 60-year loans from the Treasury, at somewhat reduced interest rates.

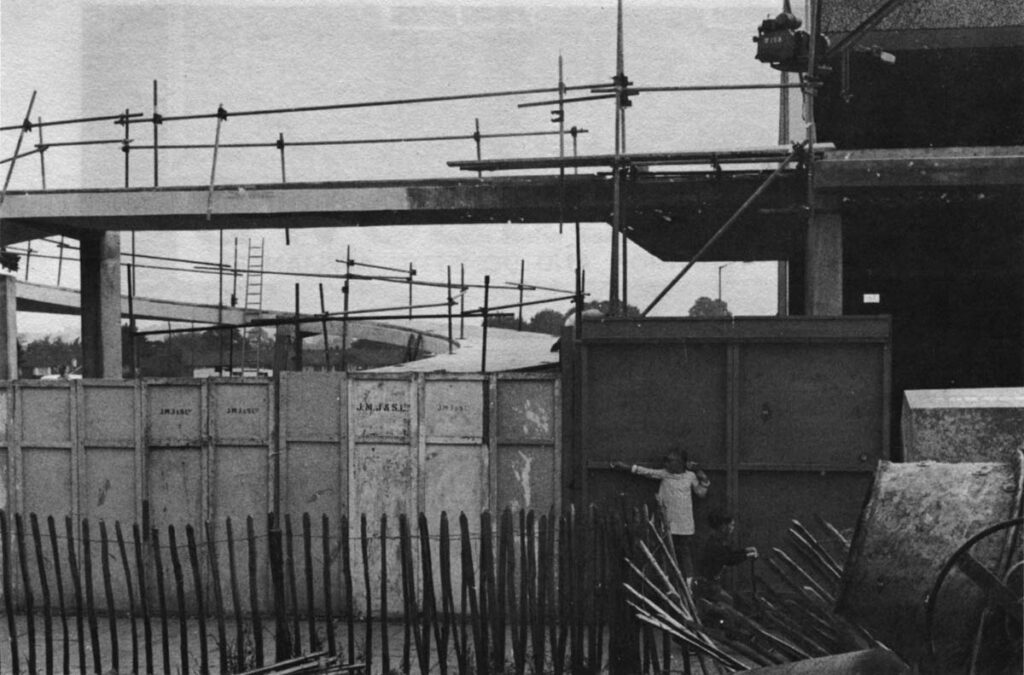

Key in the whole new towns procedure is the master plan. A master plan is an attempt to understand all the diverse elements that make up a community, and put them into their best relationship to each other. The character of the new towns has been largely set by their plans. Every change that has become necessary has been made on the plans as well, and has required approval by the Ministry of Housing and Local Government in London. By the same token, though, while it caused delay, the master plan also made possible the accomplishment of such complex tasks in short time.

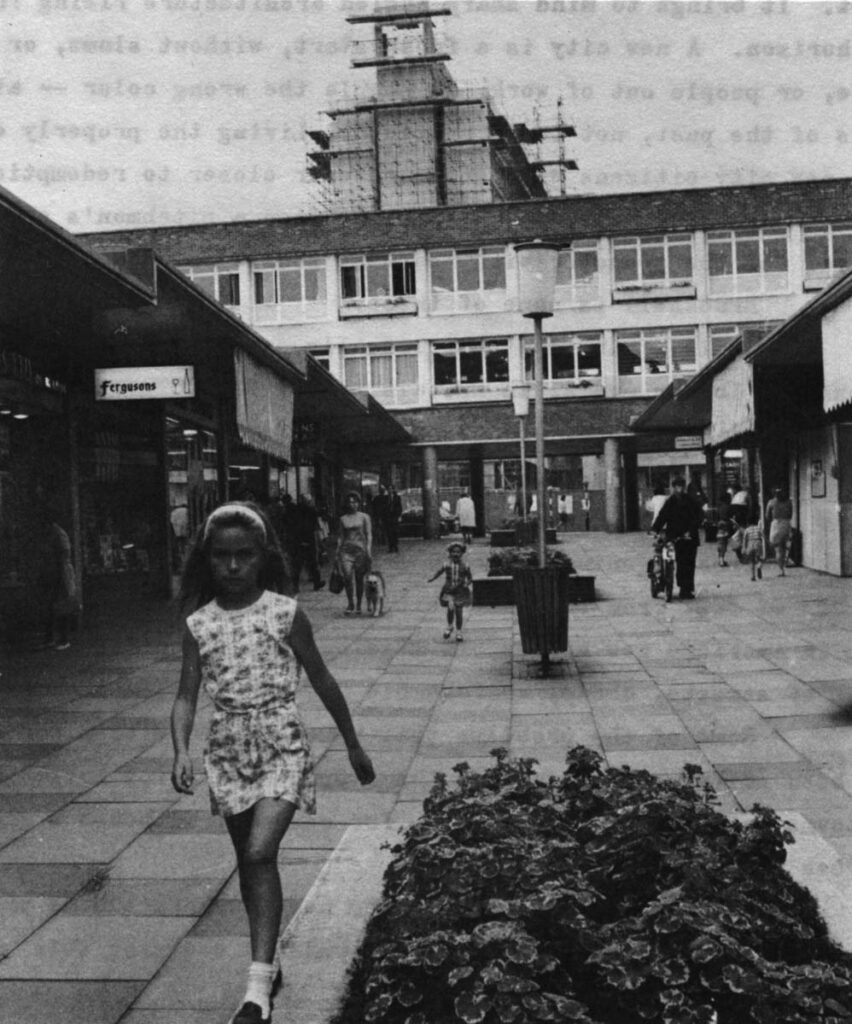

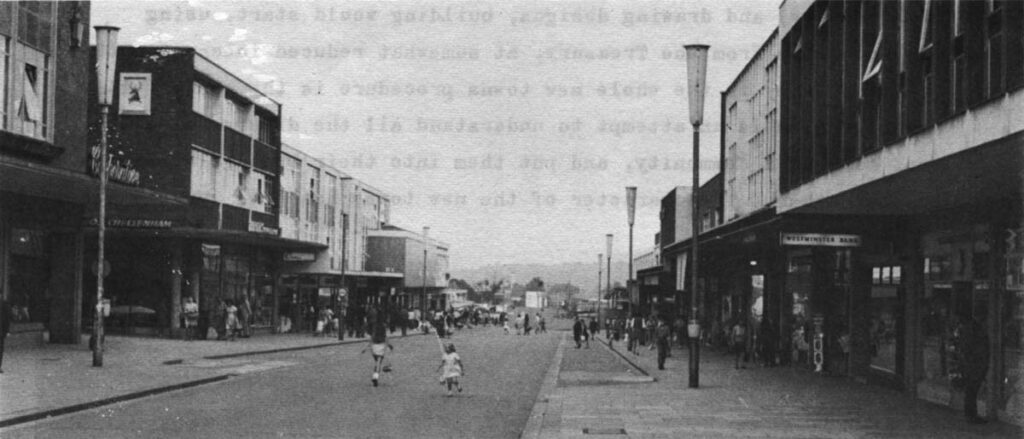

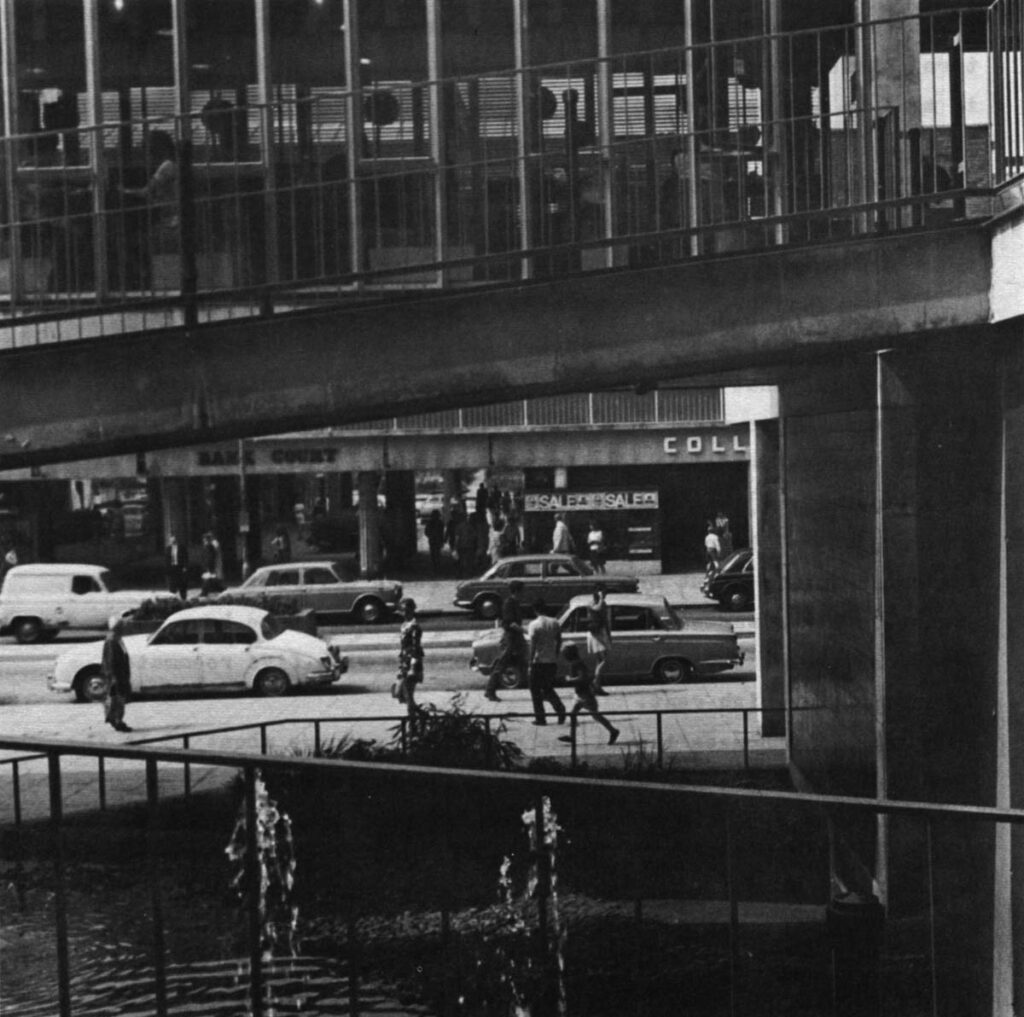

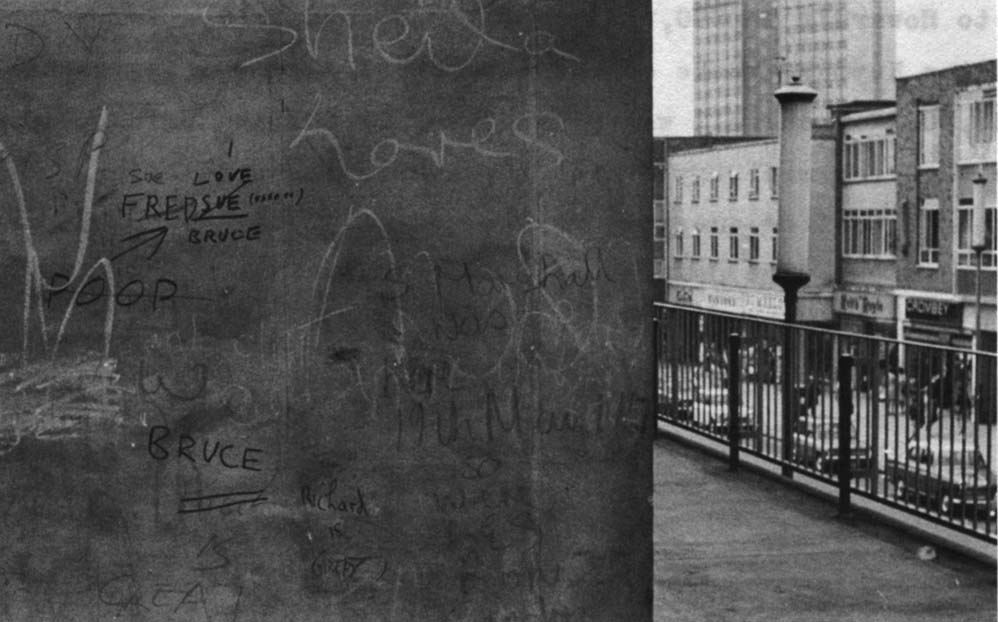

Before completion it became clear that cars were choking cities to death, and that the new towns were attracting shoppers from widely surrounding areas. Cars were halted, new plans drawn, and this empty street will one day be a shoppers' mall like the one on the cover.

Hemel Hempstead (below) was built a few years sooner. It was too late to change plans there. Shoppers and cars compete for space on Marlowes, the main street.

Bracknell is a representative result.

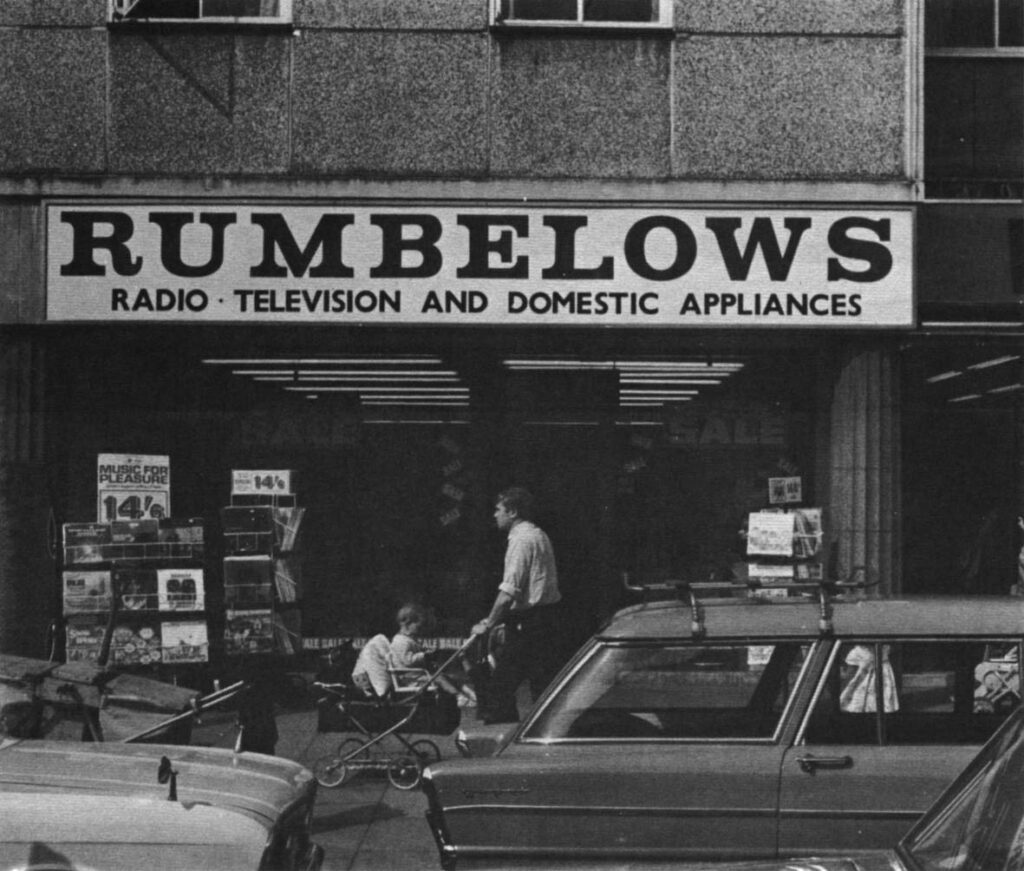

The shopping center is the focus of the town. It has 135 shops along parallel streets, connected by a shopping mall in an H shape. One of the streets has been closed to cars, the other will be when a ring road is complete. All around the ring will be parking garages. In other new towns they are complete. In Hemel Hempstead, for instance, there is actually enough free parking in the middle of town, at least for a while.

Bracknell’s shopfronts are all, of course, new. Some affect half timbering, or leaded windows or other Berkshire architectural tidbits, but the overall effect is indistinct. The goods, too, are a routine assortment, with few specialty items.

The people stand out more sharply. I recall a young family, father and stroller in the lead, mother and two older children behind, striding purposefully up the traffic-free street, their faces displaying satisfaction with the world and with their shopping mission.

Play areas are frequent, imaginative and constantly used. A huge gymnasium is surrounded by extensive playing fields. Inside, on a routine summer holiday day, is perpetual agitation of bouncing balls and children swinging from ropes.

In the middle of the shopping street six children, aged perhaps four to eight, trailed after one another in a game of follow the leader. Although it lasted half and hour, back and forth in front of busy stores, there was enough space and nobody was inconvenienced. Bicycles are everywhere. The children, glimpsed through trees or down a long grassy way, seem very free.

The factories (Bracknell has as many jobs as working residents) look disconcertingly like a newly-built college campus. Large lawns and low buildings set back under trees belie the manufacture of plumbing supplies within.

Houses in new towns are allocated to industries, which in turn allot them to their workers. There are some loopholes, but this is the basic way you get a house in a new town. This, of course, weights the population toward the young and the employed, demanding more schools than average, but fewer of the services associated with the disadvantaged.

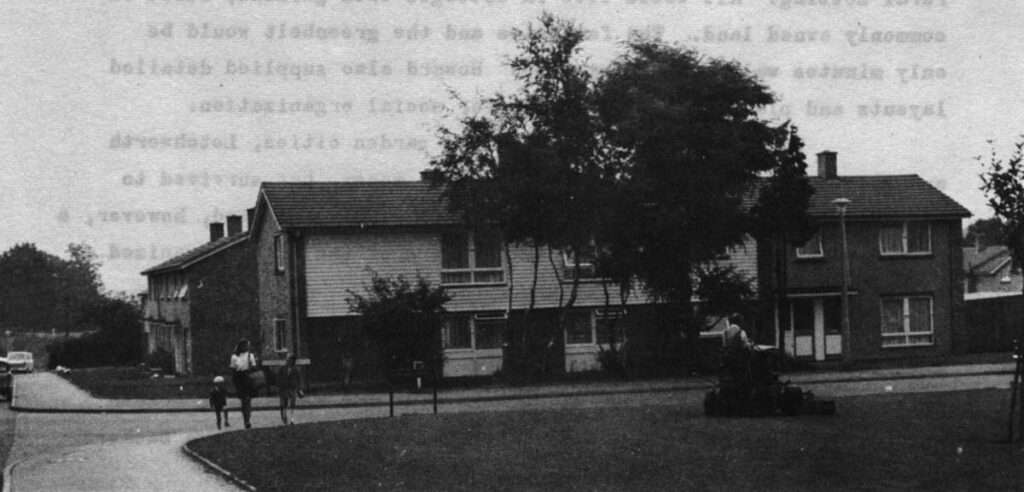

The house provided is most likely to be one of a row, have three bedrooms, and be simply and well laid out. In Bracknell it will probably be plain brick with partial clapboard siding. Rents run from $4.50 a week for a flat for a retired person living alone, to $1100 a year for a four bedroom detached house with a garage. The overall ratio of rent to earnings is 20 per cent.

Each 5000 people make a neighborhood, centered around a few convenience stores and a pub. Because they were built in turn, the neighborhoods differ somewhat in appearance. Whether there is more to the neighborhood than a name and convenience, I cannot say.

The standard of construction is workmanlike, neither shoddy nor plush. There are a few apartments, even though the doctrinaire new town theorists call them over-concentration of population. But there are only a few.

The obvious question “Do people like living in Bracknell?” can only be tentatively answered. All the houses are always full. Most families that come, stay. People talk about being part of a new thing, wanting to make it work.

One secretary mentioned the almost total lack of night life (one cinema) but said she and her friends drive 10 miles to Windsor, where there is a racetrack, or to London, 25 miles. She was enthusiastic about Bracknell. She could afford to live alone, even though her wages were lower than they would have been in London. There, she said, she would have had to live with five roommates because of the high rent.

The houses in all the new towns average about 13 to the acre. Grouped closely, as they are, this gives a very green, country impression to the large spaces between groups, rather like a suburb with fewer faults.

Distinctiveness Blurred

The new town idea has changed in 20-odd years. Some of the fervor is gone. The builders and managers and accountants have taken over from the thinkers and schemers. At the Ministry of Housing and Local Government, which builds the new towns, a spokesman was quite willing to concede new towns may one day build out into their greenbelts – an unspeakable heresy to a true believer.

Size has changed. Where the idea in the late 40’s was quite close to Howard’s 30,000, only a few new towns are still that small, and Milton Keynes, where construction will soon start, is planned for 250,000. Bracknell was planned for 30,000 and held up in mid course when the ministry decided to double its population. I have been unable to find out just why the decision was made, but presumably it was to house more people as easily as possible.

The social precepts seem to be dropping away as well. Common ownership of the whole town equipment was immediately replaced by national ownership. But now, the emphasis is shifting again, to privately owned houses on land leased for 99 years.

The degree of self government in the new towns so far is slight. Neighboring local governments, nominally responsible, have been slow to move in, even though their tax bases have been much enhanced. This has left actual governing largely to the development corporations. Corporation meetings are closed to the press and to citizens. There has been little objection.

A national movement was formed to increase participation by citizens, open corporation meetings, and have the ownership and management of completed new towns turned over to residents. It has gathered little strength.

The labor government is on record as favoring local management, and presumably that will come, although no moves have yet been made.

The analogy that keeps coming to mind is of the suburb with fewer faults. People are building Bracknell, and people are moving to Bracknell, to get a convenient place to live in pleasant surroundings. Only a few are seeking moral edification.

Little Home Rule, Little Fuss

A government report called “People and Planning” has been issued this summer. It urges that citizens, not just in new towns but throughout the country, be involved in planning and development decisions. It may be inconvenient, the report finds, but it is the right thing to do.

If they loose anything like the American organized citizen voice, they, will find public involvement as time consuming as everything else they, do. While there has been a good deal written about the report, there is little sign anybody knows how to follow through, other than holding still more public hearings.

Again, let’s use Bracknell as an example. It is under both a county and a rural district, either of which might have full local power. It is also in two water districts and another sewer district (which held up construction for three years in the early 50’s by failing to complete a large pipe). Fire and police are separate. The only local, elected body is the parish council. It is virtually without power.

The development corporation has the money, the staff, and has built the whole town. Short of revolution it would be impossible to govern Bracknell without the corporation.

The corporation in turn is tied to the Ministry by the powers of budget and planning approval. Asked just how intimate the control is, a supervisor in the ministry said they would want to know about every new garage in every new town.

In time, let us assume, the overlapping local governments will be sorted out and Bracknell will become a unit on its own. The elected government would work through some liaison system with the corporation, which would still likely, hold all the financial cards.

But until that happens there is small chance indeed for self government. Answering an annual survey on car use and employment patterns is as close as most citizens come to giving voice to their views.

The real avenue for making opinion felt, the Ministry spokesman explained, is through local government. Citizen apathy becomes more understandable in light of the virtual impossibility of knowing who to talk to, let alone getting him to listen.

A City Isn’t Enough

When there is a hypothetical Bracknell city government, the equal of any self-governing place in the realm, it will face the same pressures that threaten to render vestigial all local government in Britain.

A royal commission has this summer concluded three years of study of local government (the first such study ever, it points out). The burden of the study, called the Maud Report, is that the old system doesn’t work, it should be scrapped, and a new system put in its place.

“Local government deals with matters of closest concern to everyone,” the introduction to the report summarizes, ” – the layout of their town and its neighborhood, the look of their street or village, traffic and buses, much of their housing, the way their children’s schools are run, the care of the old and the handicapped among them, the public health services (so largely taken for granted), and a score of other things that touch their own and their neighbor’s personal interests and purses.

“Yet for the most part few trouble – or feel able – to keep in touch with what is done for them and in their name….”

“A new pattern of local government is needed urgently, to catch up with past and present changes and to keep up with changes still to come.”

The problems identified by the Maud report are these:

Fragmentation, with responsibility unclear among overlapping authorities, and many local governments too small to hire needed staff.

Lack of concerted action by localities, and the overwhelming disproportion of national government power. (57 per cent of local revenue in Britain now comes from the national government; 70 per cent in some areas.)

Antique boundaries that no longer coincide with patterns of life and work. Because of increased mobility, city and country are now blended while their governments are distinct and even antagonistic.

Doubt by Parliament (probably well founded) that local government can do what must be done. As a result national power continues to be increased, local diminished.

(This, of course, is not a bad picture of the troubles besetting American cities as well.)

Maud’s solution is to draw new “local” districts, based on size (250,000 to a million), including city and country, and simplifying the overlapping powers.

On each of these standards the new towns are a failure. They are too small. They divide city from country. Their governments are of a Byzantine complexity that frustrates everybody but the corporations.

And yet it may be a system nobody likes but the people who have to live with it, like the politician hated by everybody but the voters. There are few signs of political unrest or agitation around the four new towns I spent some time in. Of the half dozen people in new town corporations and Ministry offices that I asked, none had read the Maud report, although all had heard of it.

Without reorganization and strengthening, Maud finds, “local government will be swamped by the pressures and the power of the central authority, and a highly centralized form of government will result. To most people in England this is wholly unacceptable; but if there is no adequate counterpoise, it will come.”

I get no sense that centralization is so wholly unacceptable to most people in England, when it brings with it new houses, convenient shops and a community that somebody else takes care of.

Photos – AB

Received in New York on September 10, 1969.

©1969 Andrew Earl Barnes

Andrew Earl Barnes, Assistant City Editor of The Washington Post, is on leave for a year to study European cities as an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow.