London – London has the sort of local government setup American cities are told they ought to want. After years and decades of Royal Commissions, White Papers and endless talk, the whole patchwork of vestiges and beginnings was scrapped in 1965. A fresh start was made, the forms of government designed to match the realities of the city.

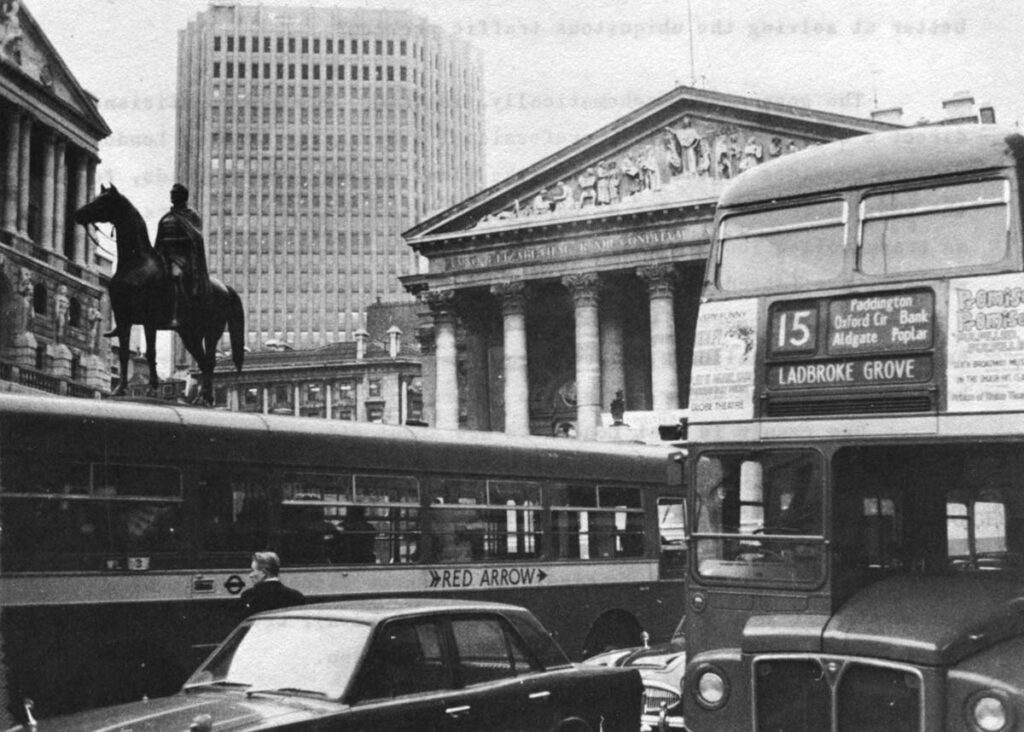

London also has strangling traffic problems. Cars came to London a little later than to the U. S., but they have come in fleets.

How to make the city serve the automobile better is a constant topic in the press, the government and in casual conversation.

The question is, does a streamlined local government do any better at solving the ubiquitous traffic problem?

The government, schematically, is this: elected politicians direct a highly specializedg professional staff. The Greater London Council provides certain things, like planning and through roads, for the whole metropolis. The 33 boroughs handle more local affairs such as trash collection and schools. The boroughs, because they are smaller, are intended to maintain closer contact with the citizens.

The independent boards, authorities and tax districts that have become the hallmark of local government in giant cities everywhere have been subsumed under the single governmental framework.

One result is that London is now about circular and some 30 miles across. It is surrounded by the Green Belt, a band of parks and farms and villages created in the 1930’s as a demarkation of the city’s edge.

Because of the reorganization, Heathrow Airport (known as London Airport when you are anyplace but in London), Croydon and Ilford are all officially, as well as actually, in London.

It is very much as though Rockville, Md., were governed as a part of Washington, along with Upper Marlboro, Md. and Fairfax City, Va., while it the same time retaining local jurisdiction over schools and welfare. The metropolitan city government role is not unlike that of an active state government.

Indeed the idea of a metropolitan setup is strongly attractive in the U. S., where many cities, like Washington, find the vitality of their tax base retreating across the Maryland and Virginia state lines, along with many of the city’s most self-sufficient citizens.

Left behind in the middle, the old part of the city, and the only part officially called Washington (although again, away from Washington, a person living in Rockville would say he was from Washington) is a distillation of welfare, race and school troubles.

Political unification of a city and its surroundings is often proposed as a solution. Daniel Patrick Moynihan:

“At least part of the relative ineffectiveness of the efforts of urban government to respond to urban problems derives from the fragmented and obsolescent structure of urban government itself. The federal government should constantly encourage and provide incentives for the reorganization of local government in response to the reality of metropolitan conditions.” (in “The Public Interest” Fall, 1969)

Traffic and highways, or motorways as they are called here, are perhaps the classical city-wide problem. A motorway that takes you halfway across town and deposits you in a traffic jam of delivery trucks and long-haul vans isn’t much help. It is small solace to know the traffic jam is actually in a different political jurisdiction.

It is the comings and goings of trucks and cars boats, trains and buses that bind a city together. Without them a city is a lot of smaller plexes put down side by side, not recognizing each other. It is the comings and goings that allow the specielization and differentiation that are the definition of an economic metropolis.

And in London, as elsewhere, congestion has been changing from an irritation into a deformity in recent years.

Citizens have more cars. At least sometimes, they want to use them. Business is more specialized, and so depends more on the parcel or the part sent across town.

City streets can hold a certain number of cars. When more cars than that capacity drive into the streets, they all stop moving. When the cars stop, so do the buses. Pedestrians are slowed. Commerce is slowed. It takes a half day to do what once took a half hour.

Cars, and trucks and buses, quickly seek smaller residential streets that are briefly less choked. It becomes impossible to sleep for the noiseq to breathe for the fumes, to let your child out for the traffic, to keep anything clean for the grime.

The rattling of dishes on the shelf as a semi-trailer passes an apartment is no longer cause for comment. In fact, the whole pattern of what cars do to cities is self-evident to any city dweller. He either accepts itq or gets sick from it, or moves out.

In London, unlike American cities, the noxious does not seem unalterable. After all$ the fogs have been cleaned up, haven’t they? Even before the final, destructive buzz-bomb raids of World War II, London was planning how to rebuild, and make the new better, not just as good.

To be more precise, the national government was planning how London should be rebuilt and reorganized.

London’s own governmentg the London County Council, was widely famous for its efficiency and progres,.iveness. But it covered only a proportion of the citizens and territory of the city. For roads itild population, the city had to be considered as a whole.

So, in 1944, the Abercrombie Plan was published. It included a detailed roads proposel, made of concenLric circles, called rini,s, connected by spokes, called radials.

It was a full, high-speed roads network, and would certainly have encouraged the use of the car as against mass transit, by making the car very convenient. It was accepted,, without the expectable oppositiong for two reasons:

There clearly was not enough money, to begin any, of the roads for a long, long time.

The roads plan was part of an overall package that made much more important recommendations.

And that’s about where London transportation has stood for 25 years – expansive talk and little action.

The rest of the Ambercrbmbie proposals are realities. War damage is practically invisible. Hundreds of thousands of units of housing, most of it public, have been built. The population density of central London has been considerably reduced. (It was the reduction of London population that led to the new towns and a scheme of subsidized emigration called “overspill.”)

For traffic, it is smallq often effective, but cheap things that have been done. Road signs are superb. Parking regulations are enforced. A problem intersection is likely to have a policeman working hard at keeping it moving.

The road building has been a segment here, a widening there, or a flyover (overpass in American taboggan in French) instead of a full road network.

Similarly for mass transit, while the Victoria Line of the underground is being extended, most of what has been done is ameliorationg not change. Placards make it plain where a bus or train goes. Frequencies of service bake been increased.

Still, if you are in London and you want to get out, you will do it on a pre-war train or on basically unchanged city streets.

It is almost impossible to converse on a sidewalk in down-town London. You will be jostled away from your companion because the sidewalks have been narrowed to make room for parked and moving cars. The noise is intolerable.

If it is bad for the walker~ it is worse for the driver, who sees the pedestrian outspeeding him.

Perhaps this is belaboring the obvious. Everybody knows city streets are like that. We very quickly come to accept the interferences and rudenesses imposed by the proximity of cars and people on city streets, the truck blatting as it splashes dirty water on your trousers.

It is no less a problem for all its familiarity. It continues to be bad for people to lose sleep and lose patience. It continues to be bad for a city when the routines of business become costlier and slower. Businesses and people come to cities because they are better, not because they are worse, twisted though we all may be.

So, how does the Greater London Council deal with “The Transport Problem?”

First, of course, it makes a study.

It is part of the law establishing the Greater London Council, as well as a constant theme in the testimony leading up to it, that there should be continuous, professional planning and research.

Dozensq and soon hundreds of people went to work on the “transportation problem.” They had a computer, big maps, trafric counters, 0 & D studies. (When you are driving and you get stopped and asked where you came from and where you are going, the man is making an origin and destination study. In theory, it tells how big a road there should be between the two places.)

On a technical level, the problem is truly formidable. It is trying to balanee a mobile with ten thoua”nd weighta. A change on one side – a new road, a.factory destroyed by fire, anything that ,altbrs where peopldego every day – and thewhole complex is out of balance.

The complex is not isolated. What happens just over the boundary, even London’s distant boundary, is crucial.

Population is a factor. In 1939 8 million people lived in London. Now it is just over 7 million. Since five years would be blinding speed to build a road, and 15 years for a road system, the question of how many Londoners there will be in 1985 is of central importance.

The largest population shifts in Britain in recent decades have not been correctly anticipated, a fact of which the planners are quite aware. Forecasting simply remains inexact. A team was charged with making accurate projections, in 1965, for 1970 and 1981. When by 1968 they were still unable to give good figures for 1970, it was decided to look out the window for the short term picture and tell the team to concentrate on 1981 and 1991.

Planning roads9 you need to know not only how many people at some time far in the future, but how much each of them will be driving. Currently, fewer Londoners are driving more.

What time of day are they driving? A thousand cars a day is one thing, but if they all come in a 15 minute period, it’s quite another thing.

The final fillip, of course, is to anticipate accurately the effect the roads you build will have on the roads you need.

Making a good road plan is obviously no snapq even if people would let you alone to do it. They won’t. The pressure to turn out something, after 25 years, was considerable.

A new road plang part of a new overall master plan for London, was produced this fall. It has a ring of familiarity. It is concentric circles connected by spokes.

The professionals unveiled it, the Council has approved it, and now comes the crucial stage. Public outcry,, perhaps? – no, approval by the Minister of Housing and Local Government.

It is the national government that will come up with about threequarters of the cost of a new London road system, and it is the national government that will in fact decide whether London is to have new roads or another dust-gathering plan.

Two central questions remain to be considered before deciding whether this is a satisfactory way to plan and build a city’s transportation system:

Is it responsive? Have Londoners been asked what they want and have they been able to answer? Will the final result be satisfying to those who use it?

Is it efficient? Is this a fast way of coming up with a good answer, or a slow WaY Of producing a bad one?

There is no objective standard for measuring the responsiveness of a governmental process. Public hearings and neighborhood polls can be used to mask the most autocratic dolicies.

In theory it is the boroughs that stay in closest touch with the citizenry. In practice the boroughs were consulted very little on the plan. They are expected to elaborate the local sections within the grand framework, not influence the framework.

I also have my doubts about whether an artificially partitioned segment of 200,000 to 300,000 people is any more a cohesive unit than 7 million Londoners who at least know they are Londoners.

Westminster, the richest though not the largest borough, has its city hall in a new skyscraper. I asked six people on Victoria :Street, where city hall is located, before finding one who could direct me to it in the next block. Twenty~five would be a large public turnout at a borough council meeting.

There is reason to wonder how many people in London – “the man on the #11 bus” is the local phrase for John Doe – even know there is a major new road plan nearing approval.

It has been su-marized in the papers with varying degrees of thoroughness. But the Council documents were all printed in at most a few thousand copies. They are not written in a matter to entice a reader.

Public hearings are not a part of forming policy here. They are generally held after a plan is drawn, to hear objections. The objections come largely from organized groups whose position is known.

There are displays in a hundred places around the city. They look, unfortunately, like all displays of road proposals. I had reason to sit next to the one in County Hall for two hours, and nobody came to see it.

Well, why should anybody care, anywar. Aren’t road plans best left to the professionals? They know what they are doing.

The plan, as proposed, would cost hundreds of millions of pounds. It would raze tens of thousands of houses (the figures are unclear). Most important, perhaps, a London of freeways would be a strikingly different place. If these are not the concerns of a citizen, nothing is.

There is no doubt at all some people not only know about the plans but are very angry indeed.

In The Times last week (Dec. 4) there was a letter signed by J. B. Priestley, Yehudi Menuhin, and Henry Moore among many calling the inner ring motorway “the fatal step towards the ruination of London,” and saying the city “is heading straight for the catastrophe that has befallen many American cities.”

The letter argues, following J. M. Thomson who has a book out on the subject, that the inner ring (which would essentially connect the train stations by dual freeway) would be too big for its feeder roads, and would itself become the excuse for enlarging many city streets.

A second side of the argument is that the expense of roads will diminish the quality of mass transit, in turn aggravating the whole transportation congestion mess.

This is an unusually sophisticated case, being argued before a limited audience. More usually, as in America, the question is how much will my rates go up and will my house be taken.

Even that response is unlikely to come until the plan is set, money commit6dg and demolition beginningg when all the talk gets some reality, and fundamental changes are unlikely.

The question of the efficiency of the decision process, similarly, has no one quick answer.

There are some obvious problems: the line dividing Greater London Council roads from borough roads is unclear, and they quibble over it; the process of national government approval can involve what amounts to a repetition of the whole decision process.

The boundaries of the Greater London Council no longer match the city. Nearly a half-million commuters cross the Green Belt daily. Coordination with adjacent authorities resumes its importance.

Within the professional staff, too, coordination has been a problem. Instead of inter-agency negotiations, there are now intraagency meetings. A large staff working on complicated problems spends a huge amount of time in meetings, coordinating. There have been some realignments trying to simplify things.

A last point: the financial economies of scale – purchasing, hiring and the like – are not what they might at first seem to be, and the concomitant costs of administration are high.

It is where efficiency and responsiveness blend that the most difficult roblems come. At some point somebody has to say ‘these four alternatives are possible, we will pick this one’.

As an exampleg the first tentative motorways pro-osal by the specialists would essentially have paved the whole city and cost the earth. It was plainly out of the question.

Suddenly the old talk about “balanced transport systems” came to have a new cogency. London could not afford anything else. The Greater London Council formed “strategy tearas” to try to match the technical findings with the political and fiscal possibilities.

Making a strategy involves suck considerations as these:

The road that “pays” for itself best is totally glutted, because it has the most cars per hour per lane. (This idea of government services paying for themselves, a modification of “more bang for the buck” has reached the point where one borough council committee wanted to close the libraries because library fines didn’t meet expenses.)

The most effective way to cut street congestion is not to build a new road. It is to tax or otherwise restrict the users of cars. But the strategist must be aware the idea is a) not understood widely and b) not politically acceptable.

If you let the streets become too full, hoping to force drivers onto mass transit out of disgust with the delays, you will so slow the buses that nobody will ride them.

Finally, people may continue to use cars in the face of all rationality.

A decision having been takenq it is the job of the strategisty and his political mastersq to persuade. The decision has to be made to feel right- it has to confirm people’s intuition – because almost nobody is willing to follow along the reasoning by which it was actually reached.

The lack of information is not professional secretiveness. I found everybody I approached in County Hall more than willing to talk about how road proposals are made. But the discussion is hardly widespread, and in fact is unlikely to replace the theater as a London entertainment.

The first look the public gets at the plan is when they are asked to object. They are glad to do that. “My house will be taken so it is a bad plan” or “I don’t think cars belong in cities at all” or “I want to be able to drive downtown to work and I don’t want to hear about anything else.”

Like the letter to the Times, objectors group themselves, for their different reasons around what seems to be a plausible case.

The most powerful objection may in fact come from those who know and care nothing about roads, but feel the city should not spend money on anything else while people are inadequately housed.

Perhaps there is no way to persuade people they want to be informed ab,;ut matterg that will Rn qnbgtantially alter thoiv city and their purses, but the London government does not seem particularly to try. As a result, it must deal with quite a lot of uninformed opposition.

Perhaps a final example will be useful. It is undeniable that in Londong as practically everywhere~ it is impossible to get to the airport. Of 41 hours from downtown Paris to downtown London, 40 minutes are in the air. Of the two cities, London is markedly slower.

One partial solution is to connect Heathrow Airport with Victoria station by subway. Much of the equipment is already there.

The step is obvious, has been favorably studied for years, and delayed for lack of money.

Then, shortly after the creation of the Greater Lon(lon Council, whose jurisdiction includes all the territory, in question, the national government said fine, we have the money, do one final study to be aure it still makes sense and then we’ll go ahead.

Overall metropolitan government or nog it was jurisdictional squabbles that took the time. Victoria Station is in the borough of Westminster (which by tradition is called the City of Westminster).

Thus the immediate environs of the station, obviously crucial for getting traffic in and out of a new air terminalg are Westminster’s turf. The station itself is under the hegemony of British Rail, a nationalized industry.

The final quickie study, took two years to reach a somewhat tenuous agreement on what should be built. Everybody agreed all along that it was a good thing to do. But by now the money was no longer waiting, and nothing has been built.

Has London’s metropolitan government improved transit, built roads? Not yet.

I feel they have come closer to grappling with the problem as a whole, intelligentlyg than the American cities I know. London lacks the institutionalized cross purposes of so many American cities.

When it gets down to the political compromising~ and I think it clear that freeways will be built soon in Londong the final product is less likely to be missing a vital link, leaving a huge, crippled network.

The innermost ring will be conceded to the opponents9 and the less expensive outer rings built. Improvement of mass transit~ entirely missing from present plansq should be added.

The emphasis of the plans on the automobile seems in itself responsive to the public, which has made it clear it wants to drive its cars. Formal ways of soliciting and informing public participation are lacking.

The citizen will be well and professionally served.

At the same time he won’t know much about the why and how. His most active involvement in the decision is likely to be complaining about the rise in the tax rates. If it bothers him enough, he will elect new men to the Council next spring. Only one in three eligible voters have tome forward before, however. Perhaps that is as close as anybody wants to come to local government.

Photos-AB

Received in New York on December 15, 1969.

©1969 Andrew Earl Barnes

Andrew Earl Barnes, Assistant City Editor of The Washington Post, is on leave for a year to study European cities as an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow.