Paris, September 18, 1969

Molly Barnes

Molly Barnes is the wife of Andrew Barnes, Alicia Patterson Fund award winner, on leave from the Washington Post.

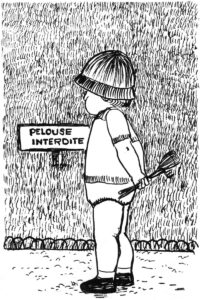

After hours of traveling in cramped spaces first priority in Paris was finding a park for the children. One look at that huge expanse of incredibly green, immaculately clipped lawn and our two small boys pounced on the grass. Guards began tweeting their whistles and waving their arms. People stared. Then I saw the sign: Pelouse Interdite – Forbidden Lawn, The children were puzzled at first but seemed to accept this new order of thing, this park deportment Paris style.

After hours of traveling in cramped spaces first priority in Paris was finding a park for the children. One look at that huge expanse of incredibly green, immaculately clipped lawn and our two small boys pounced on the grass. Guards began tweeting their whistles and waving their arms. People stared. Then I saw the sign: Pelouse Interdite – Forbidden Lawn, The children were puzzled at first but seemed to accept this new order of thing, this park deportment Paris style.

Paris has hundreds of parks and squares. Gentle green oases in the gray of Paris have been created in the centers of traffic circles, around statues and fountains and as periphery to the grand public buildings. From plots no larger than a house lot to tracts of thousands of acres, Paris has made splendid parks. In a few of the city’s more crowded sections the most park one can find in walking distance is a pleasant bench under the trees flanking the boulevard.

Paris has hundreds of parks and squares. Gentle green oases in the gray of Paris have been created in the centers of traffic circles, around statues and fountains and as periphery to the grand public buildings. From plots no larger than a house lot to tracts of thousands of acres, Paris has made splendid parks. In a few of the city’s more crowded sections the most park one can find in walking distance is a pleasant bench under the trees flanking the boulevard.

During the last part of the nineteenth century Paris was reorganized by Georges-Eugene Haussmann, Prefect of the Seine under Napoleon III. An integral part of the plans for transforming the face of Paris was the creation of new parks and the expansion of existing ones. Heretofore most parks had been private domains. Haussmann wanted parks to be horticultural works of art meant for the enjoyment of the public. Inspired by the English landscape gardens, Haussmann’s park designs became parks famous for their beauty and their enhancement of Paris.

Around the turn of the century play areas were added to the parks. This meant the addition of sand piles and the building of a few large athletic facilities such as soccer fields and cycle tracks. But today the parks remain very much the Province of the promenaders and the bench-sitters.

There is little in Paris parks similar to the beat in United States playgrounds or the adventure playgrounds in Scandinavia. Other than sandboxes children are not particularly considered in park design. The recreational athletic needs for active adults and older children are scarce. To an American it may seem absurd to reserve most of the parkland only to be looked at while so many people, particularly in the poorer, more densely populated areas are crowded into the remaining graveled spaces.

There is little in Paris parks similar to the beat in United States playgrounds or the adventure playgrounds in Scandinavia. Other than sandboxes children are not particularly considered in park design. The recreational athletic needs for active adults and older children are scarce. To an American it may seem absurd to reserve most of the parkland only to be looked at while so many people, particularly in the poorer, more densely populated areas are crowded into the remaining graveled spaces.

But I have never seen parks loved and enjoyed as much as these magnificent pieces of la Belle Epoque.

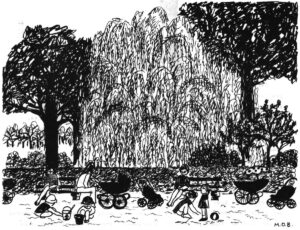

Like other families we have our everyday park, on of many formal petit parks scattered along the perimeter of the Bois de til Boulogne, one of Paris’ two immense public woods. The park is almost hidden from the public; with heavy hedges and old thick trees it isolates itself from Porte Maillot, a frantic intersection of the eight arteries. You step through the gate into a neoclassical landscape painting. Contrasting with the hundred hues of green is a formal bed of red and blue begonias and azuratums in the center of the lawn. The grounds are planted artfully with many varieties of trees and shrubs of every size, color and texture. The immense weeping willow is balanced with a group of tiny red Japanese maples and the symmetry of severely trimmed privet hedges is relieved by well-placed young weir maples. The whole park, about four acres, has a ceiling of chestnut trees, huge and solid over this bucolic landscape in microcosm.

Petit Park is surrounded by a low functional iron fence. Through the gate and to the left behind strong steel mesh is a list of the park regulations – substantially the same for every park in Paris. You may not bring dogs or transistor radios; you may not destroy the plants; you may not sing in a choir without the permission of the park superintendent. And of course you may never tread on the lawn. Opposite the regulations is the guard house where an all-seeing guard sits in a small glass office.

Meandering through the central lawn are soft brown gravel paths with plenty of benches along the ways. An old man, impeccably dressed, has a bench to himself and reads his newspaper as he does there everyday. Three women sit knitting, jumbles of string bags overflowing with fruit on the ground beside their bench. They are enjoying their break from the morning marketing. At the far end of the park, beyond the bench where the lovers are embracing, there is a large graveled space. Four elderly men are having a game of boules and in this quiet place you can hear the thud of the small balls hitting the ground.

Meandering through the central lawn are soft brown gravel paths with plenty of benches along the ways. An old man, impeccably dressed, has a bench to himself and reads his newspaper as he does there everyday. Three women sit knitting, jumbles of string bags overflowing with fruit on the ground beside their bench. They are enjoying their break from the morning marketing. At the far end of the park, beyond the bench where the lovers are embracing, there is a large graveled space. Four elderly men are having a game of boules and in this quiet place you can hear the thud of the small balls hitting the ground.

About a quarter of the entire park is fenced off to be a play area for small children. Behind the high hedge disguising the fence there is an entirely different atmosphere from the sedate cul-de-sacs in the rest of the park. The whole area is paved in gravel mixed with millions of small bucketsful of sand brought from the sandbox by years of children. One end of the yard has an ornate water spigot and the only other furniture is the benches lining the area and a huge central sandbox.

There are no pony rides here, nor sailboats for hire, nor puppet shows as there are in the grand parks. But day after day in this and many other small parks like it in Paris mothers bring their children to play. Saturdays, fathers often accompany their offspring, leaving the mothers at home. Petit Park is near and familiar.

In the United States mothers frequent the neighborhood parks of a city almost as much for themselves as for their children. The small ones play and the women enjoy adult conversation and a release from isolation. It seems different with the Parisian women – very little conversation among the park habituees. On a fine day there may be six people jammed onto a single bench but a polite mental distance is always maintained.

Around nine thirty on a weekday morning the migration to the park begins. Elegant mammas push the big overstuffed prams with one baby reclining on an embroidered pillow, the older baby perched at the other end. At a stately pace they maneuver their ways through the mad traffic, through the park gate, then through the inner gate to home free – their accustomed bench near the sand pile. The toddler is deposited in the sand with his toys. Now the baby is rearranged under the fringed sunshade of the pram and mamman gets down to her needlepoint or novel.

Around nine thirty on a weekday morning the migration to the park begins. Elegant mammas push the big overstuffed prams with one baby reclining on an embroidered pillow, the older baby perched at the other end. At a stately pace they maneuver their ways through the mad traffic, through the park gate, then through the inner gate to home free – their accustomed bench near the sand pile. The toddler is deposited in the sand with his toys. Now the baby is rearranged under the fringed sunshade of the pram and mamman gets down to her needlepoint or novel.

These children who dig in the sand everyday might be on their way to a birthday party. The boys are dressed in short tight pants, high topped white boots and perhaps a white sweater and cap. Girls always wear dresses and they learn to squat in a certain way as they play so their lacy panties will stay clean. Babies are not allowed out of the pram until they can walk. The rough surface would be hard on the knees as well as the dainty baby clothes. But these little ones don’t seem to mind the restrictions of the harness and the carriage. They enjoy the activity they see around them and the passing attentions of the older children.

Keeping up the Parisian image the mothers and aupairs themselves are splendidly dressed, coiffed and made-up – an unsettling eight for the uninitiated foreigner appearing in jeans and loafers. They carefully brush off the bench before sitting down. The preference is for a seat on the sunny side of the sandbox so to catch an extra bit of sun tan.

The only times I have had a bench all to myself have been on the hot days when I let my boys bring buckets of water from the spigot to make large piggy puddles and dams in the sand by, my seat. The curious French children gather around to watch or even stick a tentative toe into the muddy backwash, but they never join in.

Despite the distance kept and the pervasive formality park members are attuned to all the little nuances of daily life in the park. When a new group arrives or a child begins to squabble knitting needles slow momentarily and pages stop turning. We’ve all been secretly fascinated by the progress of a romance between the Brazilian diplomat’s nanny and the park gardener. At first the gardener merely lingered nearby as the nanny plumped the pillows in the pram of her smallest charge or dispensed a fresh shovel to the older one. As he nipped a stray weed here or clipped a privet shoot there the gardener began tentative overtures. Now they sit together everyday talking eagerly and just looking at each other.

Some events are more alarming. An early celebrator of Bastille Day found his way into the children’s area. As it is customary to let your children wander quite freely in the fenced area no one noticed at first that the children were visiting the untidy old man on the far bench. The odor of alcohol became strong and it was discovered that he had been pouring helpings of his battles of aquavite into the children’s buckets. Instantly taking action, mothers called the guard who sent the man on his way. That day the children made ninety proof rivers in the sand pile.

Afternoons and Thursdays the older children out of school come along to the park with their younger siblings. The sandbox resembles the Metro at rush hour. All sorts of activities are going on simultaneously nearby; jump ropes, bicycles, and balls all move in different crazy directions. It seems hazardous but the Parisians take it all calmly and accidents are rare.

In the middle of the afternoon the mothers begin to rummage in their bags for the pastries, cartons of yoghurt and bottles of mineral water they have brought for the children’s snacks.

At closing time when the guards are starting to rattle the huge padlocks on the park gates hardly a trace of the day’s activity is left. There is no litter, not a forgotten shovel or shoe.

Sundays a Parisian family will endure endless traffic to get to one of the larger parks offering besides the sand pile and sitting more choices for family recreation. If the family goes to either the Bois de Boulogne or the Bois de Vincennes, the two immense areas of parkland on the east and west sides of the city, it can have a walk in the woods and on the grass with a freedom not possible in the rest of the Paris parks.

The Jardin d’Acclimatation in the Bois de Boulogne is unique in the park system. A grand melange of amusement park, zoo, playground and garden, it is a favorite Sunday destination for Parisian families. From the Porte Maillot you take the miniature train into the Jardin and from the debarkation place inside the gates you wander according to your mood and how much money is in your pocket. It costs nothing to swing on a swing but a short ride on the carrousel costs a franc. You can ride a gentle boat, or more dramatic, a grimacing camel.

The middle of a Sunday, people-watching here reaches new heights. Past the ticket booths families in Sabbath finery move towards a commotion in a series of open sheds. Watching from a distance it’s impossible to tell what has come over these normally dignified people. In little groups they seem to be hopping and staggering about, convulsed again as an old grandmother enters one of the cubicles. We soon discover that all the hilarity is over the distorting mirrors lining the shed, on the walls of every cubicle. There is a stoutish family; parents, grandparents and four children are lined up in amused satisfaction to see themselves as Giacometti stickmen. The house of crazy mirrors is free.

Received in New York on September 22, 1969.

©1969 Andrew Earl Barnes

Mr. Barnes is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published, with credit to Andrew Barnes, The Washington Post and the Alicia Patterson Fund.